Photographer Gordon Parks inspired a new generation of artists. Here are some of their stories

- Share via

In one of Gordon Parks’ photographs from 1942, a Black woman named Ella Watson stands erect, staring wearily into the lens. Watson, a widow supporting herself and two grandchildren, is pictured at her place of employment, where she cleans offices. She holds an upright broom in one hand, a mop by the other, in a stance echoing Grant Wood’s “American Gothic” painting. Rather than a rural house behind her, offering support and shelter, she stands before an American flag — the symbol of a country that has slighted her.

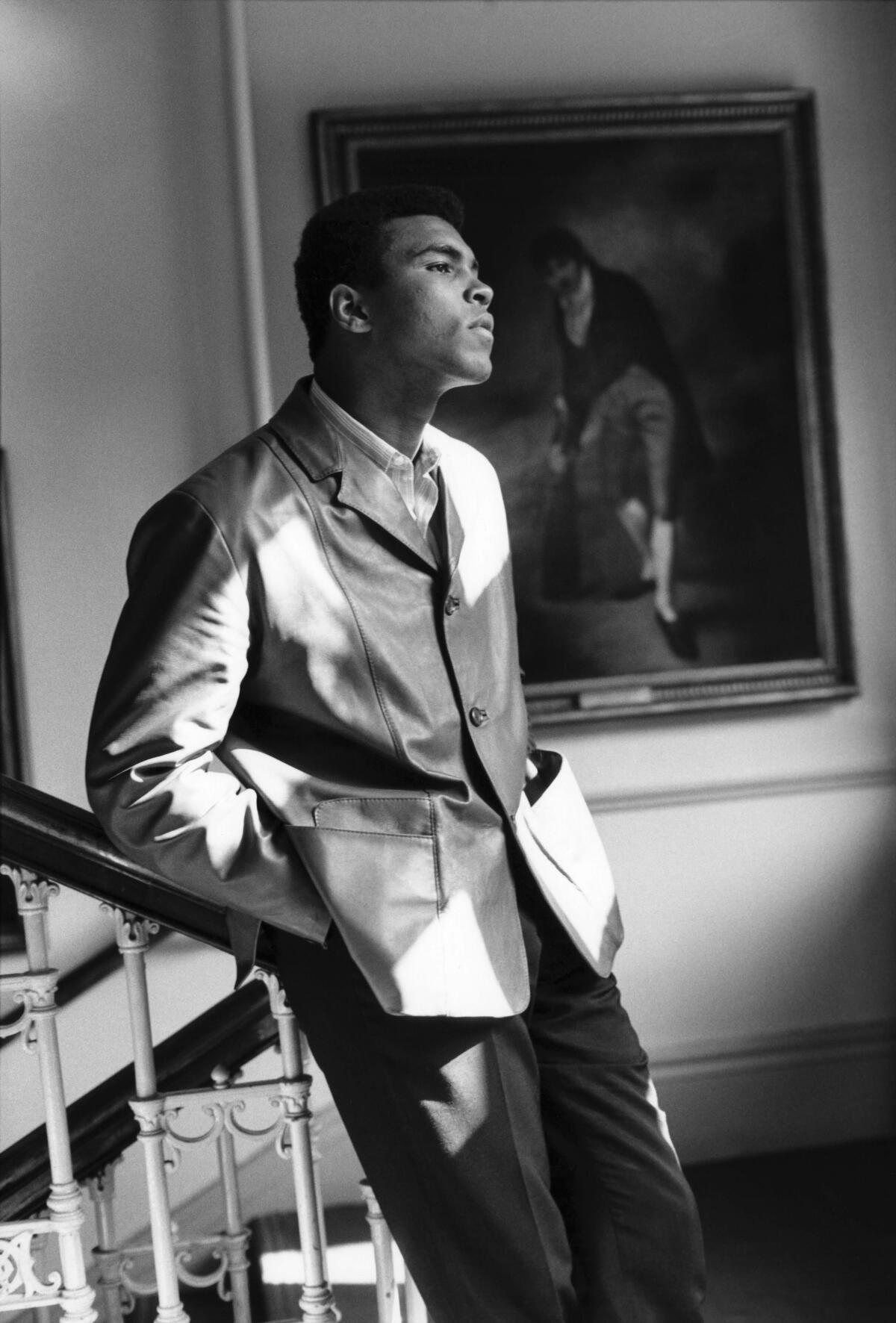

The image, also titled “American Gothic,” oozes the kind of intimacy between photographer and subject that Parks was known for. As a photographer for “Life” magazine from 1948 to 1972 — the publication’s first African American photographer — Parks traversed the country, capturing images that shined a light on racism, poverty and untold Black experiences in America. He got close to his subjects — which included Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali as well as Harlem gang members and families in the Jim Crow-era deep South — often embedding with them for weeks to develop the kind of access and nuanced understanding that resulted in strikingly candid, searingly honest imagery. He walked a precarious line, connecting with his subjects while also maintaining photojournalistic distance.

“He had the ability to slipstream between high and low culture, rich and poor, to weave in and out of spaces and gain subjects’ trust,” says John Maggio, the director of a new documentary about Parks. “But he almost never broke the fourth wall, he almost never became part of the story.”

“A Choice of Weapons: Inspired by Gordon Parks” debuts on HBO Monday night, a date that commemorates the photographer’s late November birthday. The film is less a chronological telling of Parks’ life story (the 2000 HBO documentary “Half Past Autumn: The Life and Works of Gordon Parks” details that) and instead focuses on his legacy — specifically on the generation of photographers, activists and artists that he inspired. Singer-songwriter Alicia Keys and rapper-producer Swizz Beatz are executive producers and luminaries including Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Bryan Stevenson, Ava DuVernay and Spike Lee are among those who make appearances in the film, speaking to how Parks — who was also a film director, composer, author and activist — shaped their bodies of work and the world.

“At a time and in a society where Black people were told far too often that we’re criminals, that we’re ugly, that we’re less worthy to have the spotlight on us for any reason,” DuVernay says in the film, “Gordon put a lens and a light on us for ourselves and allowed us to see the elegance of the lives that we live and the places where we are.”

Photography itself — particularly the medium’s ability to provoke social change — is very much a central character in the film. While conceptualizing the documentary, Maggio had been thinking about how nearly every American has a camera in their phone these days. Activist-oriented, DIY socio-historical documentation is now ubiquitous in our culture, particularly on social media — something Parks’ work was a precursor to.

“I was struck by the power of these images documenting police abuse and murders and everything on the streets, and how important that imagery has become to our national story,” Maggio says. “And Gordon seemed to fit perfectly with that. He always said his camera was a weapon to fight social injustice. I thought: there’s so many people doing that today. And I wanted to meet the people who were using photography in the same way.”

Three contemporary photographers provide the connective tissue for the film’s structure: Baltimore-based Devin Allen, LaToya Ruby Frazier of Chicago, and New York City’s Jamel Shabazz. Their personal stories and insights about Parks add another layer of intimacy and immediacy that courses through the documentary’s narrative.

Allen, 33, took an unexpected route to becoming a photographer. He grew up in West Baltimore, where he dealt drugs and where the death of close friends was a regular occurrence. At 24, he turned to co-hosting poetry nights with a friend; snapping photos of those live events and featuring them on Instagram was a welcome escape.

He discovered Parks after Googling “famous Black photographers,” instantly connecting with his work. Following Parks’ lead, Allen took to roaming the streets, capturing images of Baltimore’s neighborhoods and the people who call the city home.

“I decided I wanted to be Gordon Parks,” Allen says. “And I set out to do that.”

In 2015, Allen found himself chronicling the volatile Baltimore protests over the arrest, and subsequent death in police custody, of 25-year-old Freddie Gray. The photos he uploaded to Twitter caught the attention of the BBC, which interviewed him for a story featuring his pictures. Soon Time magazine called, eventually putting one of his images, shot on April 25 of that year, on its cover. Allen’s work is now in the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

“Police brutality is a part of the culture in Baltimore, we grew up with it,” Allen says. “It was like: ‘this is life, this is the way it is, we can’t change anything.’ But finding out about Gordon, studying his work, it helped me understand that I had a voice. And the camera allowed me to amplify that voice.”

Frazier, 39, always knew she would be an artist while growing up in the Pennsylvania steel mill town of Braddock. She studied photography at Edinboro University, but learned about Parks from a homeless woman she was making portraits of at a nearby shelter at the time.

“I came back with the portrait that we made together and when I handed it to her, she said: ‘this reminds me of a man I once saw on PBS, Gordon Parks,’” Frazier says, adding that she raced to a Barnes & Noble afterward and bought a book about Parks.

The next semester she learned more about Parks in a photography class, which touched on his aforementioned “American Gothic” portrait, one of his most famous images. Watson, the woman in the image, was a so-called “charwoman” or janitor at the time. The photograph was taken at the Farm Security Administration offices in Washington, D.C.

“That photograph by Gordon taught me how to speak through a photograph and make social commentary about the United States,” Frazier says. “This image asks the viewer a question, which is: ‘what is the value of a Black woman’s life in America?’”

Frazier now focuses her lens on working-class communities, healthcare inequality and environmental justice issues. She spent five months living in Flint, Mich., photo-documenting how the city’s water crisis affected residents. Last year, she photographed Breonna Taylor’s family for “Vanity Fair.” It’s work she feels would make Parks proud.

“I think that the images that I made speak to his spirt and his influence,” she says.

Growing up in Brooklyn, Shabazz, 61, started taking pictures of friends when he was 15 years old. He went on to work as a corrections officer at Rikers Island where he saw, up close, how the crack epidemic devastated Black youth at the time. Inspired by Parks, he set out to document vibrant sides of youth culture in New York City in the 1980s, including the hip-hop scene.

Shabazz’s work has since been featured in galleries and museums internationally. But these days he’s as focused on teaching the next generation of budding photographers — including with the Bronx Museum of the Arts’ Teen Council and the Studio Museum in Harlem’s Expanding the Walls project — sharing his passion for the medium as it relates to social responsibility. In a sense, he’s a conduit, channeling Parks’ vision.

Parks was influential on Maggio, the film’s director, as well. Growing up in Buffalo, N.Y., in the late ’70s and early ’80s, the son of an artist father and homemaker mother, Maggio was fascinated by his parents’ compendiums of Life magazines. Parks’ imagery was “gritty, visceral, brave,” as Maggio remembers them. They played a pivotal role in shaping the future documentary filmmaker’s appreciation for visual storytelling. (His “Mr. Saturday Night,” a documentary about Bee Gees manager Robert Stigwood, premieres on HBO Dec. 9.)

Maggio recalls one image, in particular, that made an impression when he was around 8 years old. It’s from a series for which Parks spent a month chronicling the daily life of an impoverished Harlem family, the Fontenelles. In the photo, a beleaguered-seeming Bessie Fontenelle and four of her children huddle at a local social services office called the Poverty Board.

“It was so moving. It was probably one of the most intimate photographs I’d ever seen at that time, at that age,” Maggio says. “You could just see all of their pain as she’s looking at the head of the agency, who’s clearly giving her information she didn’t want to hear.”

Parks’ work resonates just as powerfully today. The title sequence of the film features a montage of imagery from Black Lives Matter protests and other recent news events intercut with Parks’ images from civil rights movement protests. The unfortunate parallels are striking.

“What Gordon was documenting, sadly, is still coming around,” Maggio says. “These issues have not gone away.”

Parks may have chosen the camera as his weapon in fighting social injustice — and intimacy as his ammunition — but Maggio would encourage viewers to get creative in embracing activism and sparking change.

“That’s the takeaway — we can all choose our weapons to fight these things,” Maggio says. “It doesn’t have to be a camera. It could be a pen, through advocacy, the legal system, music. It’s a very powerful idea. And it’s one Gordon really believed in.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.