Just 3% of L.A. landmarks are linked to Black history. One project aims to change that

- Share via

Getty and the city of Los Angeles are expected to announce Tuesday the launch of the African American Historic Places Project, a three-year initiative to identify and preserve landmarks that represent Black heritage across L.A.

Led by the Getty Conservation Institute and the Office of Historic Resources within L.A.’s Department of City Planning, the project will address a disparity in local landmark designations: Only about 3% are connected to African American heritage.

The goal of the project is to more accurately reflect the history of the city.

The Office of Historic Resources knows that its landmark designation programs do not yet reflect “the diversity and richness of the African American experience in Los Angeles,” said Ken Bernstein, principal city planner and manager of the office. “There’s much work to be done to rectify that disparity and ensure that the heritage of African Americans in Los Angeles is fully woven into our historic designation, and recognition of historic places in Los Angeles.”

Wilson, co-curator of a groundbreaking new MoMA exhibition, counteracts architecture’s inherent racism with ideas framed by the Black experience.

The project is a continuation of a nearly 20-year partnership between the Getty Conservation Institute and the city on local heritage projects.

In 2005, a city-matched grant of $2.5 million from the GCI launched a program to identify and map places of social importance, including historic districts, bridges, parks and streetscapes.

Data from surveys conducted between 2010 and 2017 led to the creation of HistoricPlacesLA, a digital portal designed to inventory, map and contextualize the city’s cultural heritage sites. In 2018, the Office of Historic Resources developed a model to guide preservation work in Black communities, using themes including civil rights, religion and spirituality and visual arts.

Building on previous research, the African American Historic Places Project was also driven by the deaths of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, the global uprisings last summer and a reckoning within the conservation sector, said Susan Macdonald, head of the Buildings and Sites Department at the Getty Conservation Institute.

The institute began thinking more deeply about “how might what we do and why we do it and how we do it actually be somehow contributing to ongoing biases in relation to planning and historic preservation,” Macdonald said. “How might some of the processes and practices that we undertake be really barriers to social justice and how might it be contributing to social injustice.”

Architectural designer Demar Matthews is using the Black vernacular — language, art, landscape, even hairstyles — to inform his work.

Getty and the city will soon launch a search for a project leader and will convene an advisory group made up of local leaders and cultural institutions within Black communities. According to a Getty spokesperson, the organization is contributing about $500,000 toward the project.

Over the next three years, the project will work with local communities and cultural institutions to identify landmarks for official historic designation. Bernstein anticipates 10 additional sites associated with Black history will receive city historic-cultural monument designation.

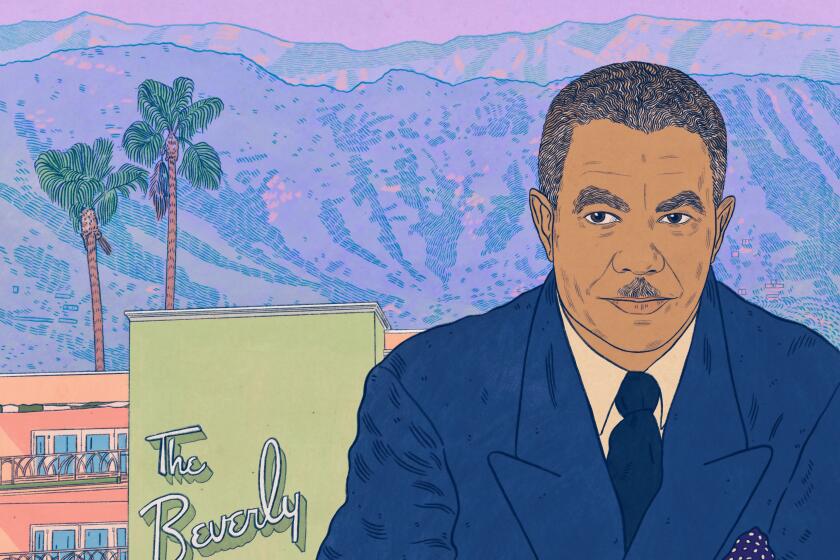

Among the 3% of landmarks connected to Black history are the Lincoln Theatre on Central Avenue, Maverick’s Flat on Crenshaw Boulevard and 28th Street YMCA, designed by architect Paul Revere Williams.

Six buildings that tell the design story of Paul R. Williams, the first Black architect in the AIA. His work is little studied, but his archive, acquired by the Getty and USC, is about to change that.

Another goal of the project is broadening the idea of what can be considered a landmark. Many of the city’s landmarks received their designation based on architecture, but preservation is not only about buildings, Bernstein said. Landmark designation can “extend beyond the physical to take in what might be considered more intangible heritage.”

Traditional approaches to historic preservation often did not take into account, “in many cases, some of the sites associated with many of our communities of color in Los Angeles had not been the subject of previous research or scholarship that elevated, lifted up those voices and those histories,” Bernstein said. “Our program is very much a reflection of what had previously been researched and documented.”

With only about 6% of the city’s 1,200 historic-cultural monuments associated with communities of color, Bernstein said, the project could also serve as a model for future initiatives.

Cultural heritage and landmarks represent history, Macdonald said.

“If they don’t accurately reflect that history and past, then you’re getting an impoverished or a misreading of history so I think what identifying cultural heritage places does, it actually tells the true story,” Macdonald said. “It can be used as a vehicle to rectify erasures of history.”

The 46-year-old theater association collapses after more than 50 members pull out. Critics say Ovation Awards mistakes reflect long-standing problems.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.