How a Compton artist’s lost prison painting found its way to the Hammer Museum

- Share via

Fulton Leroy Washington knows, all too well, the rules around making art in prison, those strict regulations for inmates working in the well-guarded hobby shop: no sharp-edged tools, no oil paints with chemicals that could be used for tattoos and no canvases larger than the storage locker lest the works get stolen or vandalized at night.

Washington, who goes by Mr. Wash, spent more than 20 years behind bars for three nonviolent drug offenses he said he did not commit. Over those two dark decades in various correctional institutions, Mr. Wash painted photo-realistic portraits of other inmates — up to 75 works a year, he said, factoring in his other drawings and tattoo designs — and gained attention in the media along the way.

The Los Angeles native’s story is well known in art circles: He was arrested in 1996, convicted in 1997 and, because of prior nonviolent drug offenses, sentenced to life imprisonment due to federal mandatory minimums at the time. President Obama commuted his sentence in 2016. Mr. Wash now lives in Compton, where he paints, works on proving his innocence and is a criminal justice reform advocate for others. He has a fashion line, Wash Wear, and was the subject of a 2019 Webby Award-winning short documentary about his life.

Lesser known is the story behind one of his paintings, “Mondaine’s Market.”

The work hangs in the Hammer Museum in Westwood as part of the “Made in L.A.” biennial. But it nearly didn’t make it there. Mr. Wash lost track of the painting while he was incarcerated, created a replica of it last year for the biennial, then found the original in Kansas City, Mo., in May. Both versions are on view in the exhibition, which this year also takes place at the Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens in San Marino.

“It’s been a journey, that’s for sure,” Mr. Wash said on a visit to his apartment, a small one-bedroom crowded with still-drying canvases, coffee cans stuffed with paint brushes and splotchy palettes on nearly every surface.

Hammer curators Lauren Mackler and Myriam Ben Salah first approached Mr. Wash about inclusion in the exhibition in 2019. They had seen an image of “Mondaine’s Market” online and requested the portrait for the show. It depicts John L. Mondaine, a fellow inmate at Florence Federal Correctional Institution in Colorado whom Mr. Wash painted more than 15 years ago.

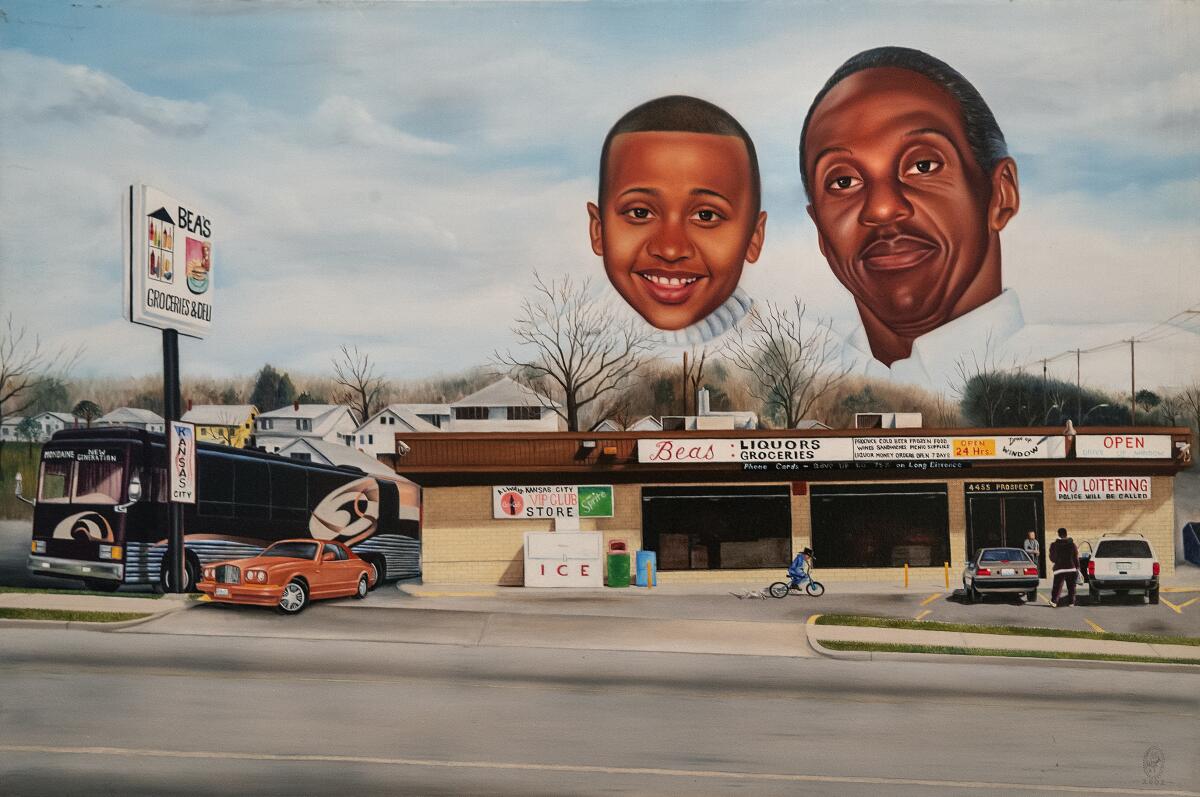

In the work, Mondaine’s enlarged, disembodied head floats in an overcast sky alongside his grandson’s head. Below is the Kansas City grocery store, Beas, that Mondaine owned. Mr. Wash — a contractor and welder who taught himself to paint in prison — obtained photographs of the site from Mondaine’s family and copied minute details from the location, along with imagery from magazines, into the piece, such as store signage, license plates and a bus’ LED destination screen. He even painted the interior of the store — shelving, stacked merchandise and a register — then painted over it, tinting the building’s windows so the inside is barely visible.

He and Mondaine designed the work together, Mr. Wash said, in the prison’s hobby shop (painting in one’s cell was prohibited at the time), talking for hours about imagery, proportions and placement. It took Mr. Wash two years to complete the work in 2005.

“He wanted a painting describing his legacy,” Mr. Wash said of Mondaine. “He came to me and said he wanted a picture of the store. He figured he was probably going to die in prison, and he wanted to be in the sky, surrounded by clouds, with his family.”

Mackler and Ben Salah felt the painting represented a body of Mr. Wash’s work depicting inmates in real and imagined landscapes, outside the prison walls, where — on the canvas, at least — they could connect with loved ones and assert their identities. The curators were also struck by the level of detail in the work.

“He’s a really skilled painter with a unique sense of composition,” Mackler said. “But the level of detail in that particular painting, personifying and animating the figures and architecture, was really exciting. There are worlds within worlds in the Mondaine painting.”

But there was a problem: Mr. Wash, now 66, had long ago lost track of “Mondaine’s Market” — along with Mondaine himself, who was released in 2005. The painting had been shipped to Mondaine’s family when Mondaine was still behind bars. (Inmates were not allowed to keep hobby shop works more than 90 days, Mr. Wash said.) But Mr. Wash had never been in touch directly with Mondaine’s family because, he said, there’s an unofficial rule: Don’t connect with other inmates’ families.

“You could get stabbed and killed for that,” Mr. Wash said. “If anything happens to their house, their family, I don’t wanna get blamed.”

Any business around his paintings — procurement of the photographs from which Mr. Wash worked, payments for portraits, the shipping of finished works — was handled by one of Mr. Wash’s eight children, a family friend, his lawyer or the organization Help Us Help Wash, founded by his supporters around 2013 to aid his legal defense. The organization also assists other individuals who say they have been wrongfully convicted.

Mr. Wash’s art liaisons, however, didn’t typically keep sale records, nor could they keep track of inmates who frequently moved within the prison system or their families. Commissions were just too plentiful. Mr. Wash’s talent earned him respect in prison, where he also taught art classes, and he said he had a waiting list of up to two years for new portraits.

Mr. Wash searched for the Hammer painting for more than four months. The shipping address was no longer valid, and phone numbers were out of date. Mondaine, by now in his 70s, was not on social media. Mutual friends turned up nothing.

The Hammer curators suggested Mr. Wash paint a replica of the work from memory, using the only photograph Mr. Wash had of the painting.

“But trying to paint a complex picture like that from a photograph?” Mr. Wash said. “The details were super small. First I said: ‘No.’ Two or three times. Then, finally: ‘OK, I’ll try.’”

Re-creating the work as a free man was a vastly different experience, Mr. Wash said. The most striking difference was scale. No longer confined to working on small canvases that would fit inside his prison storage locker, Mr. Wash went big with the replica, more than doubling its size on a 4-by-5-foot canvas.

“I’d never had the opportunity to paint in oil that large before, it was an opportunity,” he said. “But in making it a larger picture, it required new techniques — the thickness of the paint, the precision of the brushes, how long the paint takes to dry. I still painted with the same brushes I painted with in prison, but it was harder. There were new decisions.”

Free time was also an adjustment. In prison, Mr. Wash had been allowed just two-hour stretches to paint, so he was forced to work quickly and efficiently. Creating the replica in the COVID-19-era shutdown last spring, he had nothing but free time. He hunkered down in his living room — “kids can’t come by, grandkids can’t come by, nobody can visit” — painting for 12 to 16 hours straight until his body ached.

“With an unlimited amount of time to paint, your calculations are different. It can take longer,” he said. “Which is better? I’m still figuring that out.”

Some details in the original painting, particularly building signage, were too small to see clearly in the photograph of the work. Mr. Wash scanned the image into his computer and enlarged it, but the details were still blurry. So he improvised, resulting in tiny differences between the two works. One version of Beas market advertises hamburgers, phone cards and money orders; the other, pizza, Lotto cards and check cashing. The bus’ destination in each work is different.

All the while, as he painted, Mr. Wash kept searching for Mondaine and the original painting. Finally, through a string of mutual associates, Mr. Wash located Mondaine in Kansas City, living with his wife and son. He was 73 and blind.

The painting was hanging in the living room, above the couch. “They’d cherished it,” Mr. Wash said.

So much so that when Mr. Wash showed up on their doorstep weeks later to retrieve the work for the exhibition, as they had agreed on over the phone, Mondaine had a change of heart.

“But I told him, ‘Hey man, it’s me, Mr. Wash, you can trust me.’”

When the painting arrived at Mr. Wash’s apartment days later, he placed it beside the replica, which was still drying. It was the only time he saw the works together before they were shipped off to separate museums. Seeing the works side by side, nearly identical, brought a sense of accomplishment but also felt oddly melancholic, he said.

“It made me question myself. Are the energies of paintings equal in terms of detail, depth, the amount of time?”

The original “Mondaine’s Market” hangs prominently at the Hammer, and the replica is on view at the Huntington. The biennial engages themes of duality and reflections, so the mirrored works, positioned 25 miles from each other, have added resonance. (The museums’ galleries are closed, but the exhibition is installed and parts of it are viewable online.)

The Hammer is also showing paintings from Mr. Wash’s teardrop series. Each portrait — of public figures such as Obama and Michael Jackson, along with fellow prison inmates — features robust tears rolling down the subjects’ cheeks. Tiny figures and narrative vignettes appear inside the teardrops.

On Feb. 11, the Hammer will stage a free virtual discussion between Mr. Wash and assistant curator of performance Ikechúkwú Onyewuenyi that will touch on the artist’s experience, his painting process and criminal justice reform, among other topics.

Mr. Wash also will show paintings in the group exhibition “Shattered Glass,” opening March 20 at the Jeffrey Deitch gallery in Los Angeles.

He was so energized by creating the larger replica for “Made in L.A.” that he painted an enormous work for the Deitch show, a 4-by-5-foot memorial portrait of Kobe Bryant shedding basketball tears — especially poignant on the one-year anniversary of the athlete’s death this week.

“To finally see what it feels like to paint in a larger size, the difficulty in that, that was the greatest accomplishment, something I was always deprived of,” he said.

The mirrored “Mondaine’s Market” works represent a melding of the past and the present for Mr. Wash, he said as well as a chance to bend another rule:

“You get a second shot at a few things,” he said. “This was one of them. A chance to do things differently. That’s a positive. I feel so blessed.”

'Made in L.A. 2020: a version'

Where: Hammer Museum in Westwood and Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens in San Marino (exhibition opening is dependent upon county COVID-19 tier rating and related guidelines)

When: Through April 25

Info: Online viewing links at hammer.ucla.edu

Virtual event: Mr. Wash in conversation with Ikechukwu Onyewuenyi, 5-6:30 p.m. Feb. 11; free. Check the Hammer website for details, including how to RSVP and receive an invitation to join

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.