How a vital record of Mexican indigenous life was created under quarantine

- Share via

It is the middle of a plague — “a pestilence so great and universal, that already it has been three months since it started, and many have died and many more continue to die.”

This does little to stop a group of scholars who have sealed themselves off from the world in a Mexico City convent, where they toil on a series of volumes devoted to indigenous knowledge.

For the record:

11:54 a.m. March 26, 2020An earlier version of this post stated that the Getty Foundation helped fund recent digitization efforts of the Florentine Codex. That effort was led by the Getty Research Institute.

If before the plague their goal was to create a historical record, it’s now become a race against time and disease: The pandemic is claiming lives outside of their walls. They continue to work even as they run out of pigments to color the illustrations that will accompany their text. It is simply too risky to leave the safety of their cloister to go looking for supplies.

“I don’t know how long it will last or how much harm it will do,” writes Bernardino de Sahagún, the Franciscan friar in charge of the endeavor. “I don’t know what will be of this pestilence.”

He wrote those words in 1576.

Almost 500 years later, they couldn’t be more resonant.

Sahagún’s potent descriptions of a terrible plague are tucked into a colonial encyclopedia created in the late 16th century by a group of indigenous scholars at the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco.

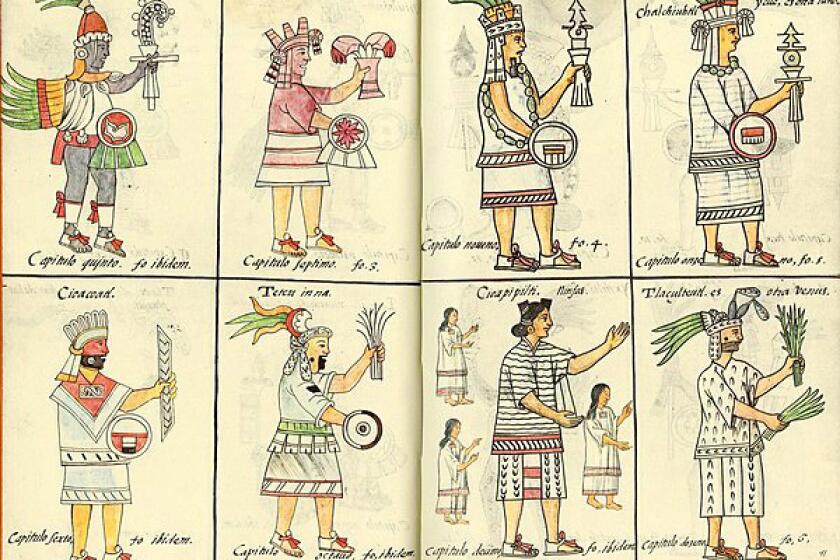

“The General History of the Things of New Spain” — better known as the Florentine Codex — is a massive 2,000-page compendium of Nahua (a.k.a. Aztec) life in the Valley of Mexico, where Mexico City is now located. In both Spanish and Nahuatl (the Nahua language), the codex is composed of 12 handwritten books featuring almost 2,500 illustrations, which are bound into three massive volumes that now reside at the Laurentian Library in Florence, Italy.

The last two books were created during a smallpox pandemic. As the contagion took its toll and supply lines for pigments fray, color disappears from the illustrations partway through Book 11. By Book 12, it’s as if all life has been drained out of it.

“To read that and see it,” says Mesoamerican scholar Kim Richter of the Getty Research Institute, “we can empathize with this text in a very different way now.”

Coronavirus: Here’s the latest list of L.A. County communities with cases

In a world turned head over heels by the new coronavirus, it is instructive to look at another cataclysm: the Americas during the 16th century, when European colonization shattered the old indigenous order through war, settlement and, most notably, disease. And not just one disease but several. A lethal cocktail of smallpox, measles and influenza — European illnesses to which indigenous people had no immunity — that decimated populations all over the continent.

(A study published by scientists at University College London in 2018 estimates that 90% of indigenous populations throughout the Americas died from disease in the 16th century — so many it cooled Earth’s climate for a number of decades as untended fields were taken over by carbon dioxide-absorbing overgrowth. It’s an event referred to as “the Great Dying.”)

I buried more than 10,000 bodies, and at the end of the epidemic, I caught the illness and was very ill.

— Bernardino de Sahagún, Franciscan friar

In Mexico, this played out in a series of pandemics throughout the 16th century. The first, in 1520, came a year after explorer Hernán Cortés arrived on the shores of the Yucatán Peninsula.

“There came to be prevalent a great sickness, a plague,” reports Book 12 of the Florentine Codex on this terrible event. “There was indeed perishing; many indeed died of it. ... No longer could they move, no longer could they bestir themselves ... And when they bestirred themselves, much did they cry out.”

Similar pandemics struck in 1555 and 1576, the latter being the one that Sahagún refers to in the section in which he wrote: “Since the plague started until today ...the number of dead has increased; ten, twenty, thirty, forty, fifty, seventy, eighty die everyday.”

If the Florentine Codex marks the creation of a historical artifact — and a brilliant, richly layered work of art — in the face of certain death, it is also an object that speaks to survival and resilience.

It is the story of a group of authors determined to record their history even as fatal illness strikes just beyond their walls.

“They would not have seen their mothers, their fathers, their sisters and their brothers,” says Diana Magaloni, author of “The Colors of the New World: Artists, materials, and the Creation of the Florentine Codex.” “And it was so that the memory of them would continue.”

It is also the story of a book, and the knowledge contained within it, that, against all odds, endured the ravages of history. Shortly after it was created it was sent to Spain, after which its whereabouts remained uncertain for centuries. It reemerged in Italy in the late 18th century — a time capsule of indigenous life, fully intact.

Albert Camus’ “The Plague,” read in quarantine for the first time, warns us to reset our own priorities

“It’s a connection to that world — all the animals, all the beings,” says Magaloni, who is a deputy director at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. “It’s comprehensive knowledge. It’s something amazing.”

And it continuously reaches into the present.

This is partly because of the work of organizations like the Laurentian Library, which has lovingly preserved it, and the Getty Research Institute, which is currently funding a digitization effort that is creating a high-resolution scan of the codex, which it aims to put online by 2022 — with translations and tagged, searchable images.

But it has also remained alive through the work of scholars who have studied it for more than a century, and through the artists who have long been inspired by its virtuosity. (Over the last decade, volumes from the codex have been displayed around Los Angeles at the Getty Villa, the Getty Museum and the Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.)

Los Angeles painter Sandy Rodriguez creates contemporary paintings using materials of pre-Columbian artists, such as cochineal and mineral oxides. She is a student of the codex and its artistic methodologies, and for a recent show at L.A.’s Charlie James Gallery, which focused on the stories of Central American children who have died while in the custody of U.S. immigration authorities, she gathered a group of poets to create work inspired by Book 12 of the Florentine Codex, which tells the story of the conquest.

“We talked about imagining being one of the tlacuilos [scribes], sequestered and writing your history,” she says, “not being able to go out and get your materials.”

By the time of the show’s March 7 closing, the severity of the coronavirus pandemic had become all too evident in the U.S. — and what had been an interesting historical exercise now had new meaning.

“It’s like we performed this contemporary history in this contemporary moment,” she says.

It’s a moment, Rodriguez says, that she is still trying to process.

How artist Sandy Rodriguez tells today’s fraught immigration story with pre-Columbian painting tools

Riffle through Sandy Rodriguez’s dense rack of painting supplies and you’ll turn up feathers, withered plants and a container of cochineal powder, the fiery red tint produced by the insect that feeds on the leaves of the prickly pear cactus.

It goes without saying that the “Historia General de las cosas de la Nueva España,” as the Florentine Codex was originally titled in Spanish, wasn’t created simply because the Franciscans were in love with Aztec learning. Sahagún conceived of it as an anthropological tool that could provide an understanding of indigenous belief systems, and therefore help facilitate the conversion of the Nahua to Christianity.

To this end, he recruited a group of young men from the Colegio de Santa Cruz to help him research, write and illustrate the epic undertaking.

The colegio had been established at the Convent of Santiago in Tlatelolco in 1536 as a place to acculturate the sons of indigenous nobility to European ways, instruct them in a variety of subjects, and prepare some of them for eventual priesthood and, therefore, further Christian proselytizing. These were the intellectual crème de la crème of early Mexican society and they learned to read and write in a variety of languages, including Spanish, Latin and Nahuatl. (Already Spanish friars had devised a system of writing the previously unwritten Nahuatl using the Latin alphabet.)

It is estimated that Sahagún began work on the project in the late 1540s, assembling draft manuscripts (such as the Códices Matritenses, which still survive) and attempting to devise a taxonomy for how the tome would be organized. In its format and its ambitious scope, it nods to the work of the ancient Roman scholar Pliny the Elder and his “Naturalis Historia” (“The Natural History”).

“It’s based on the concept of the European encyclopedia,” explains Richter. “But it’s focusing on the cultures of the Aztecs and written in the generation after the conquest of the Aztec Empire.”

While big-name celebs post treacly hymns of healing, upstart artists have created freaked-out, gallows-humored hip-hop and pop songs that better reflect our moment.

Sahagún ultimately settled on a bilingual, two-column system, one written in Spanish, the other in Nahuatl, that would cover the breadth of Nahua life: landscape, minerals, animals, food, belief systems, history, art, architecture, social classes and more. There is even an entry on “malas mugeres” — “bad women,” to quote the early modern Spanish — or sex workers.

What makes the book so dynamic is that the codex isn’t mere observation. The indigenous scholars working on the project — Antonio Valeriano, Alonso Vegerano, Pedro de San Buenaventura, Martín Jacobita, Diego de Grado, Bonifacio Maximiliano and Mateo Severino, among others — were actively interviewing the communities from which they hailed.

“They are capturing what their elders are saying, but also their colonial reality,” says Rebecca Dufendach, a research specialist at the Getty Research Institute who has been working with the codex for a decade. “They are trying to capture this world of knowledge.”

The Codex therefore reflects a distinct Nahua point of view — one that bears the imprint of people who had memory of a world before the arrival of the Spanish.

It is believed that the Nahuatl text was written first and the Spanish came after. “The Spanish is usually called a translation, but it’s more of an interpretation,” says Richter. “In some places, [Sahagún] leaves the Spanish out completely. At other times, he provides more interpretation.”

This means that the Florentine Codex isn’t simply a bilingual record of events, it’s a pair of world views, presented side by side.

Book 12, which focuses on the Spanish invasion, tells the story of the Matanza de Tóxcatl — known in English as the Massacre in the Great Temple, which took place in May 1520. In that event, Spanish soldiers massacred a group of indigenous nobles celebrating a religious ceremony at the Templo Mayor, an event whose brutality reverberated through the region.

“The Spanish text states very clearly: Here was this ritual that was happening and Pedro de Alvarado went in and killed innocent people,” says Richter. “They aren’t hiding it. But when you read the Nahua text, it’s a gruesome painful thing to read. Nahua is so poetic and it has certain repetitions. The cutting of the flesh and the cracking of bones and people trying to walk and their guts spilling.

“I get goose bumps thinking about it because it’s so awful.”

These different worldviews are brought to bear in the sections that describe disease.

Dufendach says that Spanish texts frequently frame the smallpox pandemics as an act of God. “Sahagún says in the Codex, these people have diminished because of the plagues that God sends them,” she explains.

Whereas the Nahua texts attribute the pandemics to the indigenous concept of tlazolli. “It’s this invasion of filth that has caused the disruption of their entire society,” she explains. “It was not just the war-time invasion but a moral invasion.”

In many cases, the Nahuatl language had absorbed lone Spanish words to describe phenomena introduced by the Europeans — such as the word caballo, for horse. But Dufendach says the Codex never really embraces the use of viruela, the Spanish word for smallpox, in the portions that are written in Nahuatl.

“They are understanding it on their terms,” she says. “They are trying to describe it in the Nahua language.”

A Getty Villa exhibit explores how Europeans looked to ancient Rome to understand the Mexican empire.

Disease shaped not just the ideas in the Florentine Codex, but its manufacture.

Sahagún interrupts an entry on Mexican road systems in Book 11 to write, in first person, about plagues past and present — including the one in 1555. “I buried more than 10,000 bodies,” he writes, “and at the end of the epidemic, I caught the illness and was very ill.”

In fact, it is partway through that book — about the natural world — in which color begins to disappear as the pandemic of 1576 begins to claim victims, disrupt supply lines and force its authors into quarantine.

Though it was set down on European wood-pulp paper, the pigments and other materials used for illustrations are almost entirely Nahua in origin: cochineal for red, indigo for blue, clays and orchid gums used to change tones and fix colors. Almost 500 years later, they remain in dazzling shape.

“What always strikes me is how crisp and how fresh these books look,” says Richter. “It’s so different when you hold the real thing in your hand. The colors, they look like they were painted yesterday.”

As they ran out of color, scribes used coded images to denote the tones of an object — say, placing a ladybug next to a flower to mark the red of its petals. They also reserved what pigments they had for the most important images.

Book 12, the final book, contains only three color illustrations: one in which Cortés and his men are seen entering the Valley of Mexico, featuring a landscape rendered in brilliant shades of Mayan blue and green. Another shows the moment in which a pair of indigenous armies have defeated the Spanish in battle. The last shows two Spanish soldiers casually disposing of the dead bodies of Moctezuma and Itzquauhtzin, the leaders of Tenochtitlán and Tlatelolco, respectively.

“They were saving their pigments for things that were meaningful,” says Magaloni. “The world of color has meaning for them.”

There are three illustrations on the page that features Moctezuma and Itzquauhtzin. Only the image of the fallen indigenous leaders receives color.

Little is known about the scholars who created the Florentine Codex or how they lived. Magaloni imagines a high degree of dedication — scholars attempting to put the world of their elders on paper, before it disappears — but also of deep introspection.

“It’s the opportunity to go inside ourselves and think about what we are doing,” she says, “to think about the most important things we could be doing.”

For Rodriguez, that means continuing to paint — much like the scribes of the 1570s.

“I’ve been burning my sage and my copal and asking for strength,” she says. “There would be no sanity to my world if I didn’t get up and read and then paint for a few hours.”

While others were out buying toilet paper, she was stocking up on her materials.

“I will have the supplies,” she says, “to tell the story of whatever goes down.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.