The Black Keys on the L.A. hangout that led to their funky new album

- Share via

Twenty-four hours or so before the release of their new album, Dan Auerbach and Patrick Carney of the Black Keys are sipping old fashioneds at the Chateau Marmont as they reminisce about the days when the two of them ran a lawn-mowing business with one lawnmower between them.

“And one weed whacker,” Carney says.

“One lawnmower and one weed whacker,” Auerbach confirms. “And one gas canister. All in the same minivan we used for gigs. So all of our s— smelled like gasoline and grass clippings all the time.”

This was in the early 2000s, when they formed this once-scuzzy blues-rock duo in their shared hometown of Akron, Ohio — Auerbach on guitar and vocals, Carney on drums — and immediately began playing every deserted bar they could.

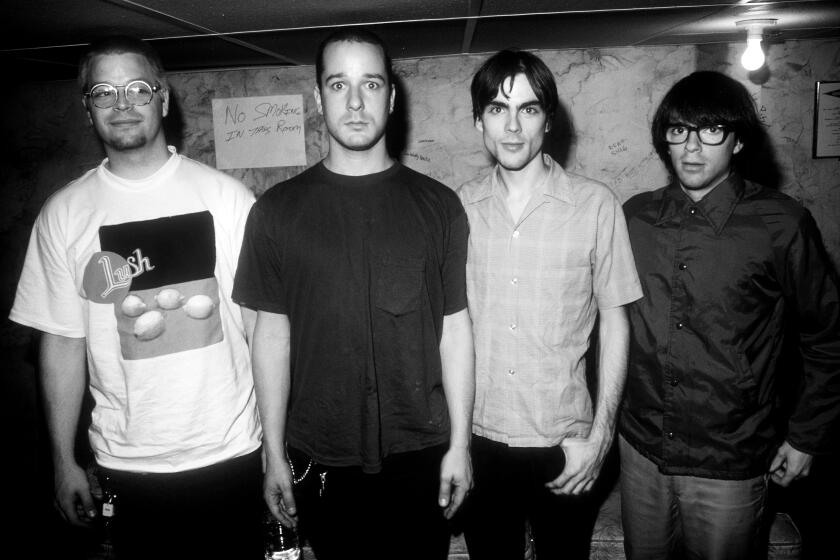

Thirty years after the release of their debut LP, the members of Weezer reveal how the Blue Album came to be.

Two decades later, the Black Keys’ lives are very different, with four Grammy Awards, a pair of double-platinum albums and, thanks to Carney’s colorful marriage to singer-songwriter Michelle Branch, a level of tabloid scrutiny the members never even thought to dread back in Akron. (More on that marriage in a minute.)

On this recent evening, Carney, 43, and Auerbach, 44, have returned to the Chateau after a day of hand shaking and meeting taking while in town from Nashville, where they both live, to promote their latest LP, which somehow has only now used the title “Ohio Players.” Earlier they had lunch at the Beverly Hills Hotel with their manager of 2½ years, Irving Azoff, whose other famous clients include the Eagles, U2 and Jon Bon Jovi.

“We’d never been there in all our years of coming to L.A.,” Carney says. “That exterior is amazing, and everything else was terrible. But I think that sums up Beverly Hills.” He looks around the dimly lighted lounge. “This is more our steez. The thing about the Chateau is that it’s so classy but the rooms kind of look exactly like an apartment I had in Akron.”

Indeed, for all their success — at one point, Carney mentions that pandemic shutdowns wiped out $20 million of Black Keys concert income in 2020 — there’s something about the band’s current situation that evokes the Black Keys’ busy first chapter, when they dropped four studio albums in just over four years. Having seriously burned out on the road, the duo went dormant in August 2015 and didn’t play a show again until September 2019; since reuniting, they’ve been on a creative tear, releasing another four LPs, including “Ohio Players,” their 12th overall.

Says Dan the Automator, the veteran hip-hop producer who was among the band’s many collaborators on the new album: “They’re cranking together right now.”

The novelty this time is that they seem to be enjoying it. The Black Keys’ liveliest effort since 2011’s hook-jammed “El Camino” (which drew a Grammy nomination for album of the year), “Ohio Players” is a loose and funky party record with catchy choruses and chewy grooves and guest appearances by the likes of Beck, Juicy J and Oasis’ Noel Gallagher. The album’s freewheeling vibe — think Beck’s “Odelay” meets the soundtrack of “Rushmore” — was inspired in part by the band’s so-called record hangs in which Carney and Auerbach haul their collection of vintage 45s to a bar and DJ late into the night; to make the album, they ventured from Nashville, where they typically record at Auerbach’s Easy Eye Sound Studio, to work in rooms in London and Los Angeles.

“Honestly, we weren’t doing anything financially smart if we were trying to make money,” Carney says, recalling long stays at the Chateau and what he called its London equivalent, the Chiltern Firehouse. “But it wasn’t about that. It was about trying to maximize the experience.”

They so maximized it that “Ohio Players” almost ended up a double album, according to Carney, at least until he and Auerbach thought better of that idea. “There’s been a couple bands that have released very long albums recently that are complete garbage,” he says. “I’m not gonna name names, but there was one that had like 40 f— songs. Dan and I realized we didn’t want anything to do with making a pile of s—.”

Though the Black Keys broke out as a scrappy two-piece, they went into “Ohio Players” eager to “flex our Rolodex,” as Carney puts it. “There’s a lot of features in rap, but in rock these days there’s very little of it,” the drummer says — a shift from the late ’60s, he adds, when “Clapton would jump on a Beatles record or whatever.” For Auerbach, the collaborations — other musicians on the record include rapper Lil Noid, Leon Michels on saxophone and multi-instrumentalist Greg Kurstin — were a way to add fresh wrinkles to the band’s established sound just as a new documentary heralds the approach of legacy-act status.

Jakob Nowell and the original members of Sublime talk about the band’s legacy, parting ways with singer Rome Ramirez and their sun-soaked Long Beach sound.

“I think it was important to us to release a new album at the same time as the movie,” Auerbach says of director Jeff Dupre’s “This Is a Film About the Black Keys,” which premiered at last month’s South by Southwest festival in Austin. “But also, we wouldn’t have been able to do this kind of collaborating when we started, or even 10 years ago,” the singer adds. “It’s really only now that Pat and I are confident enough to sit in a room and let something unfold without getting in the way.”

At the top of their wish list of accomplices, both men say, was Beck, who ended up performing on half of “Ohio Players’” 14 tracks, including the swaggering “Beautiful People (Stay High)” and “Paper Crown,” a fuzzy rap-rock-soul mash-up that also features a verse by Juicy J of Memphis’ pioneering Three 6 Mafia. Carney remembers wearing out a copy of “Odelay” as a teenager while on a family road trip from Akron to Washington, D.C.; Auerbach singles out “One Foot in the Grave,” Beck’s 1994 album of lo-fi folk songs, as a formative influence. “The way he bridged the gap as this guy who was on MTV but who was playing these Mississippi John Hurt-style songs — I was just like, Oh s—, I understand this,” Auerbach says of Beck, whom the Black Keys have known since he invited the band on the road as an opening act in 2003.

Almost as crucial as hooking up with Beck was doing it in L.A., which Carney describes as “a place that’s very conducive to creativity for us.” He lived with Branch in Toluca Lake for about a year when they got together around 2015, and he quickly “fell in love with the Valley”; these days he’s partial to the scene in West Hollywood, which offers “a culture we don’t have in Nashville,” he says. “When we’re home, I’m just watching football with my friends. But when we’re here, we’re, like, rubbing shoulders with Jason Momoa.”

The Black Keys initially set up at North Hollywood’s historic Valentine Recording Studios, where Bing Crosby and the Beach Boys once worked. “That was great because it feels like you’re in your grandparents’ basement,” Carney says. “But they were adamant that there was to be no weed smoking in the control room, which was a deal breaker.” They eventually relocated to Hollywood’s Sunset Sound, a familiar setting after the six weeks they spent there making 2014’s “Turn Blue” with producer Danger Mouse.

To get Gallagher in the mix, the Black Keys agreed to go to the Oasis guitarist in London — “which was a big deal,” Carney says, “because I hadn’t gotten Dan to leave the country since 2015.” Auerbach was playing in Paris with his side project the Arcs the night of that year’s horrific terrorist attack that killed 90 people at an Eagles of Death Metal concert at the Bataclan theater. “Definitely made me a little leery of wanting to travel for a while,” Auerbach says now. “Subconsciously, I knew we had to get back, so I thought this was a great way to do it without the pressure of a tour.”

With Gallagher, the band wrote three songs in three days, including “On the Game,” a stately ballad with Beatlesque guitars that feels lush yet proudly hand-played. Carney says it’s that slightly sloppy quality that attracts listeners to the Black Keys’ music — and not just to theirs. “I think that’s why Mac DeMarco is so popular,” he says of the scruffy indie-rock crooner. “You can smell the realness. Or this new Waxahatchee record. I don’t hear big hits but I hear something you can really get a hold of.” He laughs. “A lot of that kind of stuff misses the mark because it just takes one person in the room who wants to straighten something out to ruin it.”

One of “Ohio Players’” appealing kinks comes in “Candy and Her Friends,” where a crisp psych-rock tune suddenly slows to a half-time lurch with the entrance of Lil Noid, an underground Memphis rapper whose mid-’90s “Paranoid Funk” cassette has been a favorite of Auerbach’s since he discovered it on YouTube. “We were listening to it in the car one night in L.A. on the way back to the Chateau,” Auerbach says. “And then we were just like, ‘I wonder what Lil Noid is up to?’ We looked him up and he was in Memphis, just down the road from us in Nashville. So we invited him to the studio.”

“Dan is a genuine lover of hip-hop,” says Dan the Automator, who’s known for his work with Kool Keith, Prince Paul and Del the Funky Homosapien, among other acts. “I mean, he’s into some regional stuff that I’m not even really up on.”

On her sprawling new album, pop’s foremost musicologist explores country music’s history and leans into its wit, style and pageantry.

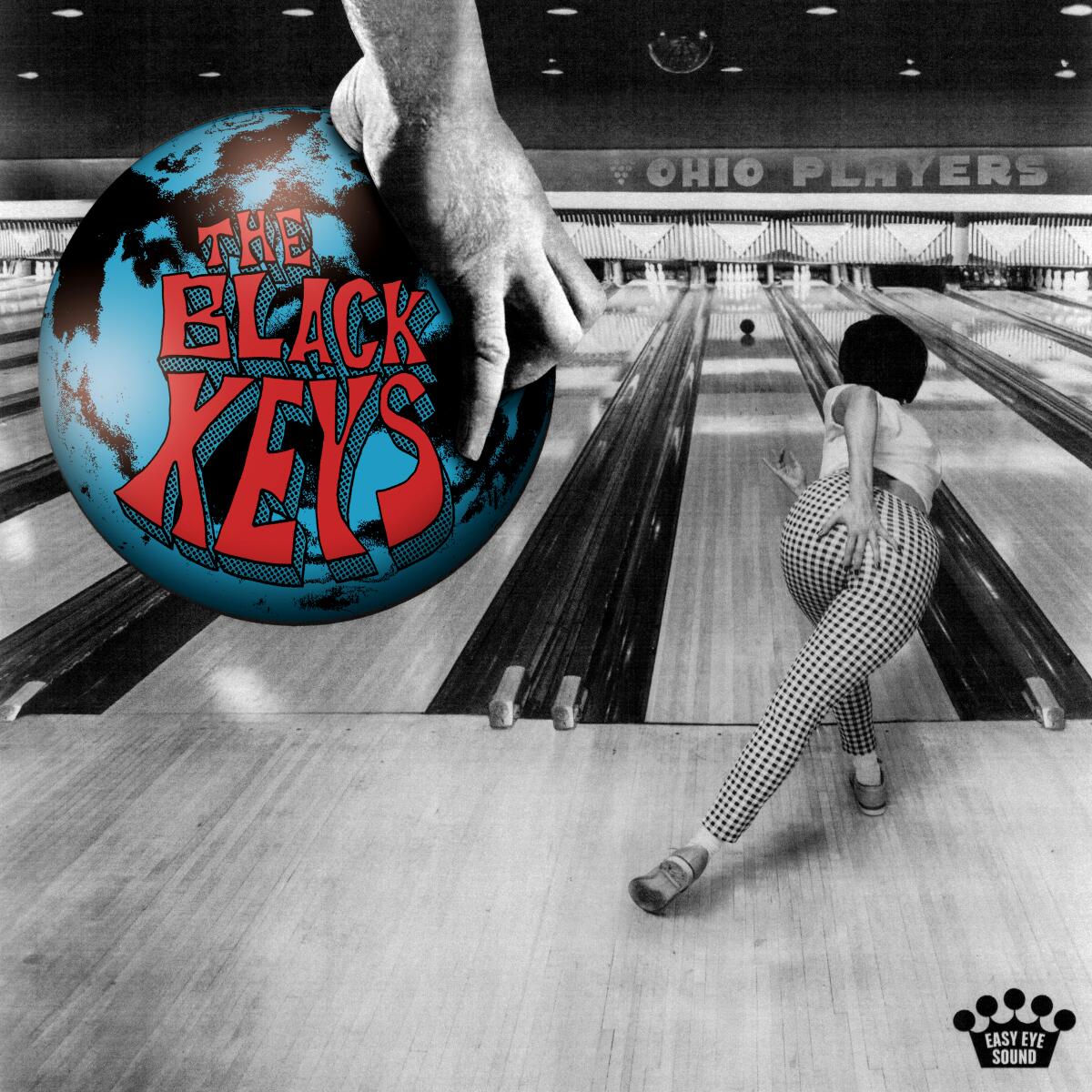

Auerbach equates the rawness of “Paranoid Funk” to that of records by Hasil Adkins, the rockabilly oddball who garnered a cult following in the ’80s and ’90s. “Pure folk art,” he calls the kind of music he’s drawn to. But of course, it’s been years since the Black Keys themselves could be considered anything close to outsiders. The night after our drinks, the band celebrates the release of “Ohio Players” (whose cover photo was shot in a bowling alley) with an invite-only gig at Highland Park Bowl filled with contest winners and music-industry types; also there dancing near the makeshift stage is Branch, with whom Carney reconciled after a messy 2022 incident in which she accused the drummer of cheating on her — in a tweet, no less — then was arrested on a domestic assault charge for slapping Carney.

Is the price of having a hit—

“We haven’t had one,” Carney interrupts back at the Chateau, which is certainly untrue given that five of the band’s songs have topped Billboard’s alternative airplay chart. So is the price of having a hit that you have to accept becoming a celebrity of some sort, with all the attention on your private life that that role entails?

“People are interested in stuff where they don’t know what’s going on,” Carney says. “And I get where the intrigue comes from. The thing is, being in a marriage is hard. I was actually just talking to my therapist about this. I was like, ‘Here’s the truth about marriage: I don’t know one that I can use as a reference that’s not unconventional or a little bit f— up.’ So whatever this is supposed to be, it’s gonna have to be its own model.”

As Carney speaks, Auerbach nods with what looks like recognition. His ex-wife is interviewed in the Black Keys doc and speaks frankly about his shortcomings as a partner. “Squirmworthy” is the word he uses to describe the experience of watching the film. “I’m glad I don’t have to watch it again,” he says. Then again, the movie recounts one of Auerbach’s most cherished experiences, when he traveled as an 18-year-old to rural Mississippi and jammed with another pure folk artist: the bluesman T-Model Ford. There’s a picture from that day that shows Auerbach, a high school sports star from a solidly middle-class upbringing, sitting in the scrubby yard outside Ford’s double-wide trailer home.

Asked how the encounter shaped his youthful conception of the musician’s existence, he says, “I didn’t see any of it like that. I didn’t think about quality of life. I just thought, I’m sitting across from the coolest person I’ve ever met, and he loves my playing. Nothing else mattered.”

And now? What would the Black Keys say if someone could guarantee they could make whatever music they wanted for the rest of their lives but only if they traded the rock star trappings for Ford’s more meager circumstances?

“Depends,” Auerbach says. “Where’s that double-wide at?”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.