Weezer’s Blue Album at 30: The inside story of the debut that launched L.A.’s nerdiest band

- Share via

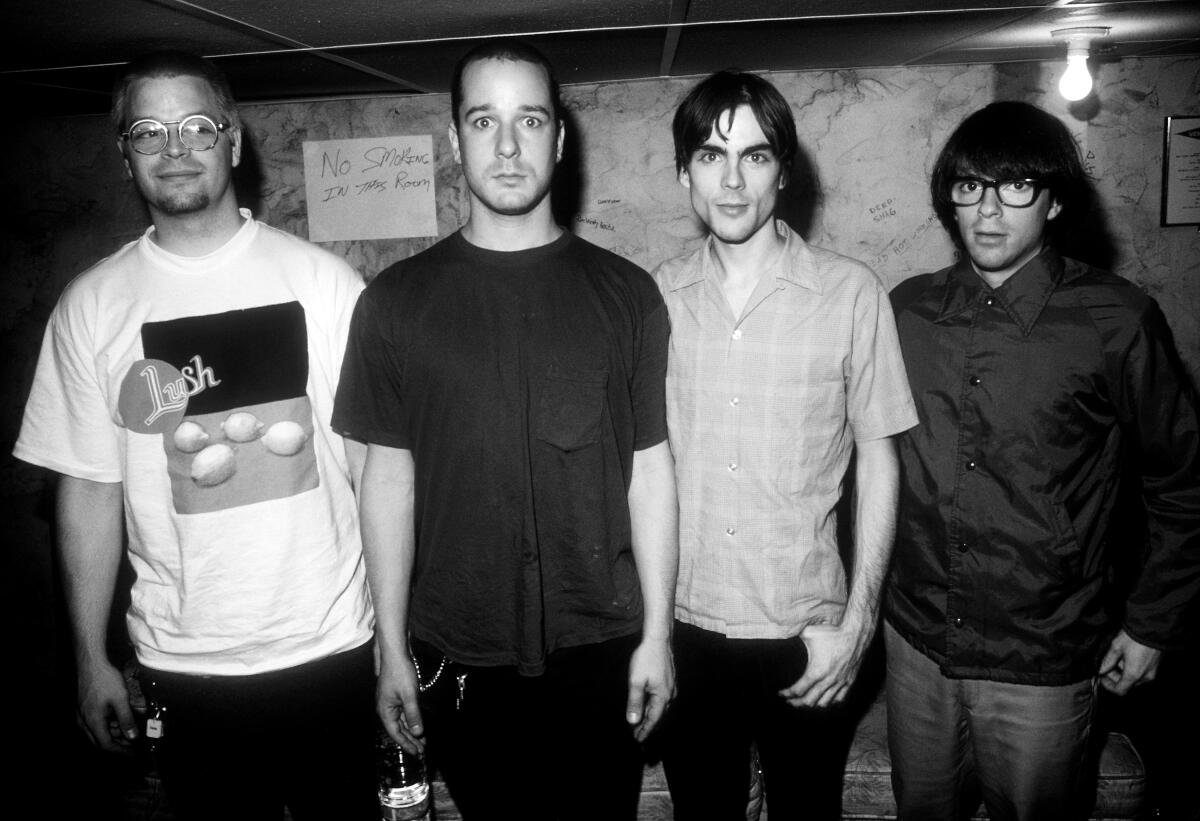

Thirty years ago, Weezer embarked on one of the more improbable careers in pop history with the release of the band’s self-titled debut album.

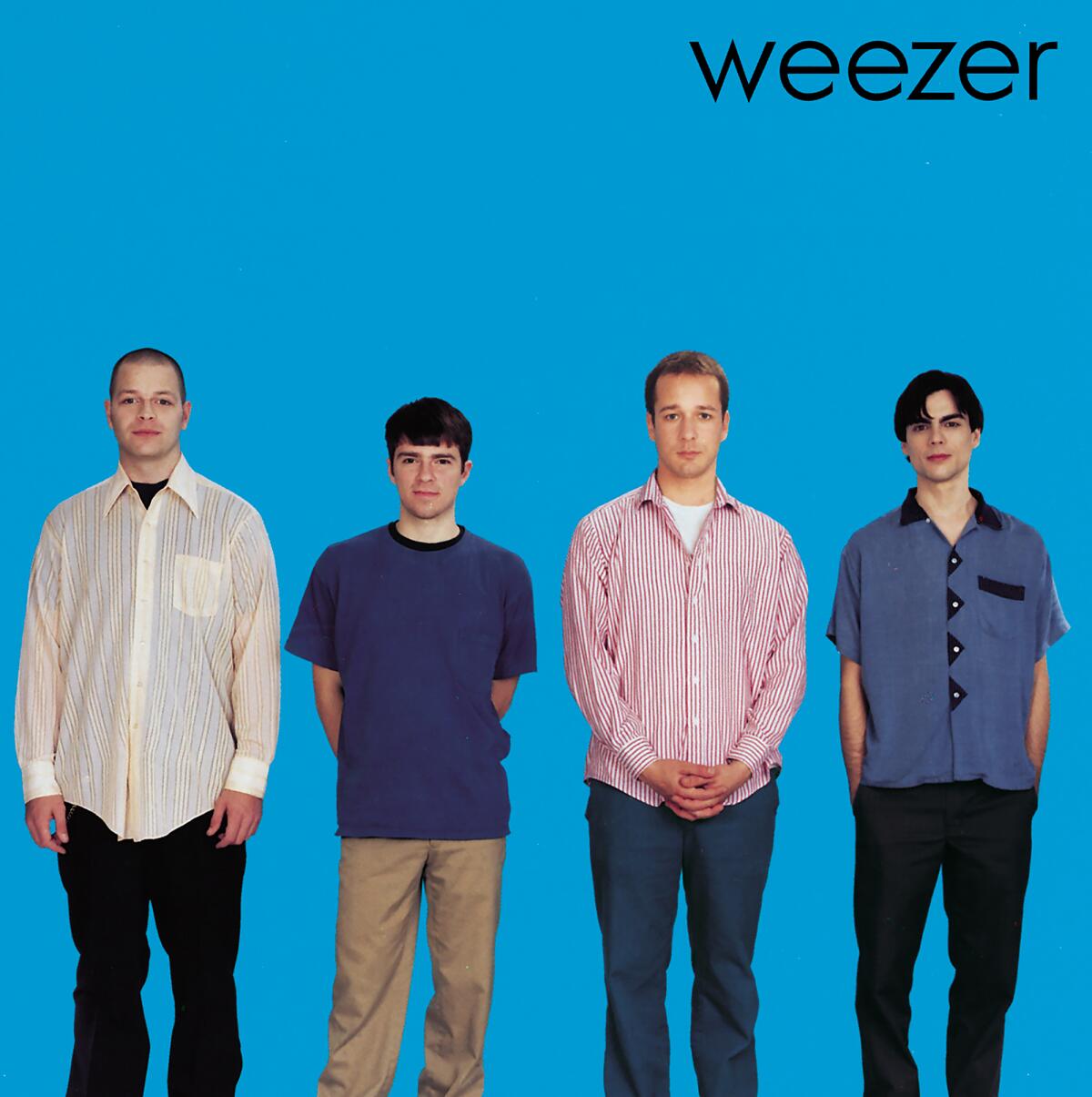

Self-consciously nerdy in an era of scuzzy post-grunge bluster, 1994’s crisp and witty “Weezer” — soon to be known as the Blue Album because of its cover (and the fact that the band kept naming additional albums “Weezer”) — wasn’t immediately hailed as charting a new direction for alternative rock. But over the decades to come, the 10-track LP would end up shaping successive generations of emo and pop-punk acts on its way to triple-platinum certification and a spot on Rolling Stone’s list of the 500 greatest albums of all time.

Now, Weezer is set to mark the Blue Album’s 30th anniversary with a tour starting in September on which the Los Angeles-based band will perform the record from beginning to end, including hit singles such as “Buddy Holly,” “Say It Ain’t So” and “Undone — The Sweater Song.” (Combined stream count for those three songs on Spotify: more than 1 billion.)

To hear the inside story of how Weezer’s debut came to be, The Times spoke with the four members of the band at that time — Rivers Cuomo, Patrick Wilson, Matt Sharp and Brian Bell — as well as a half-dozen of the artists and record-industry types who played a part in the beginning of the group’s success.

This is the oral history of the Blue Album.

I. ‘I’m never gonna be in this band’

Rivers Cuomo (singer and guitarist): If you really want to understand the Blue Album — not just the illusion of the Blue Album that we sold — you have to take it in the context of what happened right before it, which is that I moved to L.A. from Connecticut after high school with the intention of making it with my heavy metal band.

Patrick Wilson (drummer): When I first met Rivers, he still had super-long hair.

Cuomo: You can see a Judas Priest poster and a Quiet Riot poster on the inside of the Blue Album booklet — these obvious clues to where we’d come from.

Wilson: My friend Pat Finn and I had a band called Bush. This was before the other Bush. Kind of a Primus-y vibe with a skate component to it. We used to rehearse in Vernon over by the Farmer John’s slaughterhouse.

Cuomo: I got a job working with Pat Finn at Tower Records on Sunset [Boulevard]. He had a shaved head and he was cool and punk, and I was trying to get him into my band, which was called Avant Garde. He listened to our tape and said, “This is terrible — I’m never gonna be in this band.”

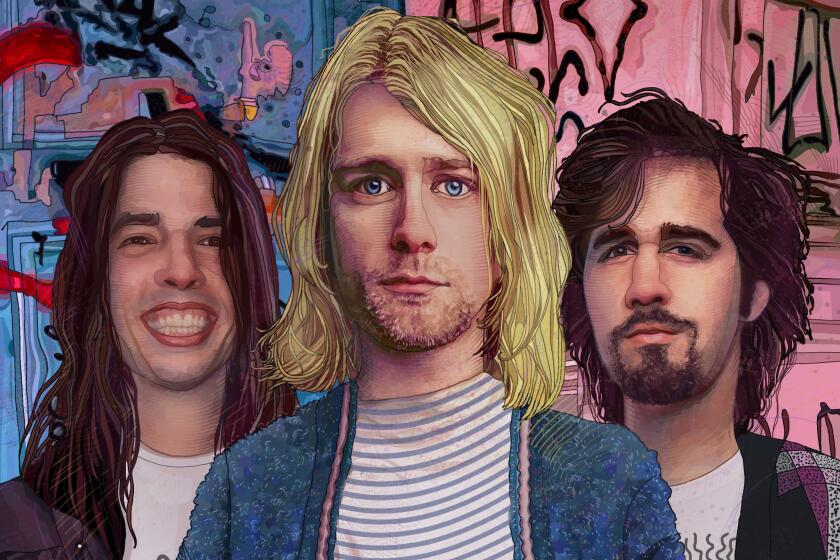

Finn introduced Cuomo to Wilson — and pushed the burgeoning songwriter to move beyond hair metal to check out bands like Nirvana, the Pixies and Sonic Youth.

Wilson: This was a time of changing into something else. It was a period for all of us to be like, “That’s not cool — this is cool.”

Ahead of Taylor Swift’s ‘The Tortured Poets Department’ and a new album by his band Bleachers, Jack Antonoff talks about ‘starting to take some of my things to the Container Store in my head.’

Cuomo: I wasn’t the singer in Avant Garde. I thought of myself as an inferior singer to the people who were singing in my bands before me — they had bigger ranges and more nimble voices. But Pat [Finn] was like, “Go write your own songs and sing them yourself.” This was during a big walk up to the top of the hill at Griffith Park. He said, “I don’t care if you think you’re not a singer. That’s gonna be a much better version of what you can do.”

Wilson: Rivers and I formed a band called Fuzz.

Matt Sharp (former bassist): I’d say it was kind of Soundgarden-ish.

Wilson: We actually had some pretty cool jams. I was so impressed with Rivers’ guitar playing. But it just kind of fell apart.

Fuzz morphed into a short-lived group called 60 Wrong Sausages, which featured Finn on bass and another friend of Finn’s, Jason Cropper, on guitar. The band played a single gig in November 1991 before it too broke up.

Wilson: Rivers lived in Santa Monica in an apartment behind Pico [Boulevard] on Urban Avenue. He had an eight-track cassette recorder, and we’d go over there and try and get ideas down.

Cuomo: I wanted to create a body of work before I put my next band together. There was so much anxiety about authenticity at the time, and we’d all just made this radical transformation from being metalheads to being alternative. You didn’t want anyone to find out what you looked like 12 months ago.

Anna Waronker (singer and guitarist, That Dog): It was clear that Rivers had some serious chops, which nobody cared about in our little world. I mean, I was doing the only thing I knew how to do. So I found it interesting that someone who knew how to do other things was choosing to … not dumb it down but, like, weird it up.

Cuomo: It seemed like you could kind of fabricate an image for yourself and it would feel real.

Wilson: Rivers said we wouldn’t rehearse until we had 50 songs. We got pretty close, but then we didn’t have anyone else to play with. I’m like, “I know a guy who plays bass.” Matt and I had worked at California Tan on the 12th floor of the Monty’s building in Westwood. They sold products to tanning salons, and Matt was singularly focused on getting clients to buy a poster that explained the California Tan system.

Sharp: I think I sold 101 when nobody else could sell five.

Wilson: By this point, Matt had moved up to the Bay Area, but I told him he should come back down and play with us. Rivers was like, “It’s not that simple,” and I was like, “Everything’s that simple.”

To entice his friend, Wilson sent Sharp a tape of Cuomo’s new songs that included future Blue Album cuts such as “The World Has Turned and Left Me Here” and “Undone — The Sweater Song.”

Cuomo: When Matt heard it, it was like a light bulb went on.

Sharp: It was the first time someone I knew created something where I thought, my God — this is something I’d listen to even if I didn’t know them.

Cuomo: He saw that this could actually work, so he moved down and was very, very aggressive about joining the band and getting the ball rolling. He found a house with a garage we could set up as a rehearsal space. At first they rejected us, but Matt talked the owners into it with his sales talent. We all got our dads to co-sign the lease.

Rounded out by Jason Cropper, the foursome practiced for the first time on Valentine’s Day of 1992 and debuted as Weezer a month later at the now-defunct Raji’s on Hollywood Boulevard. (The band’s name was drawn from a childhood nickname Cuomo’s dad had given him.) Also on the bill that night: actor Keanu Reeves’ band Dogstar.

Sharp: You could feel the energy around Keanu. The bar was packed to the hilt, line out the door. We’re thinking we’re just gonna ride this to the moon.

Cuomo: We were booked to play after Dogstar.

On April 8, 1997, the Los Angeles band That Dog released its third studio album, “Retreat from the Sun.”

Sharp: When they get offstage it’s probably 1 in the morning. We’re scrambling to get our equipment onstage, but by the time we start, everybody from their crowd has left. There’s like five people in the room.

Wilson: We covered “M.E.” by Gary Numan, and it was amazing. Probably nobody would think that now.

Weezer gigged regularly over the next few months — at Club Lingerie, at the Coconut Teaszer, at the Central (now known as the Viper Room) — to more or less the same five people. A deflated Cuomo, who’d begun to ponder the value of a college degree, gave Sharp an ultimatum.

Sharp: It was very cut anddried. He said, “You get us a record deal in nine months or I’m going to school.”

Wilson: That’s when I think we got a little more serious.

Cuomo: I remember sitting in the Weezer house one day playing an Avant Garde song called “Renaissance.” I still loved the chords — they were so emotional. So I wrote some new lyrics over it, and that was “Say It Ain’t So.”

Brian Bell (guitarist): Ironically, Jason Cropper gave me a Weezer flier at Club Lingerie. So my girlfriend at the time and I went to see them at the Coconut Teaszer. I wasn’t super-impressed, but when they got to “Say It Ain’t So,” I was like, this is a cover, right? There’s no way a local band could write a song this good.

II. ‘We needed to swing for the fences’

In November 1992, Weezer recorded a four-song demo that included “Say It Ain’t So” and “Undone — The Sweater Song.” The tape made its way to Todd Sullivan, a junior A&R executive at Geffen Records’ alt-rock DGC subsidiary that was home to Nirvana and Sonic Youth. Intrigued, Sullivan checked out Weezer’s next show.

Todd Sullivan: They weren’t a tremendous live band by any means. But there was this feeling that they had their blinders on and they knew what they were going for. And the songs — I mean, “Say It Ain’t So” was incredible. I could kind of connect the dots.

Cuomo: By that December, we had a meeting with a very small indie label.

Wilson: They offered us 15 grand to make a record. Then Slash Records offered us 80 grand. I couldn’t fathom saying no to that. But Matt and Rivers said we needed to swing for the fences.

Sullivan: They were sort of playing me: “Hey, you know so-and-so’s also interested…”

Sharp: The skills I used at California Tan were the same ones that got us a record deal.

Wilson: Next thing I knew, I had $2,500 on an ATM card, which I’d never had in my life.

Cuomo: I met David Geffen years later. I’d read this book, “The Operator” by Tom King, which was a biography — kind of an exposé — that I guess Geffen found very unflattering. But I thought it was amazing. This was 2001, in a period when I was managing the band, so I was very interested in the music business and all the tricks he pulled. So I said, “Can I meet you?” and he invited me over for lunch. I told him how we’d just come back from this sophomore slump with “Pinkerton,” and I said something like, “But it’s turned into a real cult phenomenon.” He goes, “ ‘Cult phenomenon’ is a euphemism for failure.”

After signing to DGC in June 1993, Weezer started making plans to record the band’s debut album, for which Cuomo had no interest in working with a producer.

Cuomo: Any time anyone had been in a room with us — not just in Weezer but in my earlier bands — they’d just turned the dials in a way that made things sound worse.

Waronker: I understood not wanting to ease up on the reins. We were all very pure about our music.

Sullivan: They wanted to do it by themselves at their house, but that just left too much room for disaster.

The country star’s sixth studio album, ‘Deeper Well,’ contemplates renewal and self-care after a divorce. ‘Kacey just wants to grow,’ says one friend.

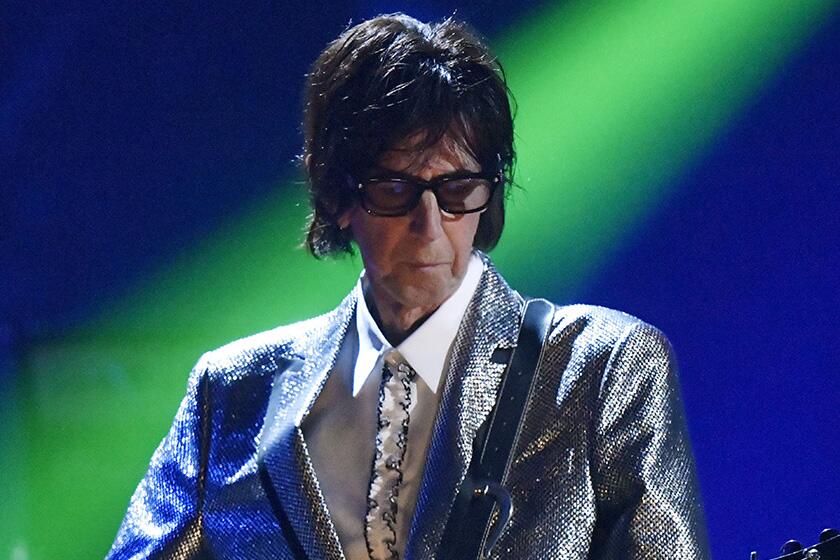

Cuomo: The record company was very insistent: “First record, you need a producer. Second record, we can talk.” So I had that in my mind, and then I was in the grocery store and I heard “Just What I Needed” come on over the PA. I was like, That sounds like Weezer — let’s get that guy. I didn’t know who that guy was.

It was Ric Ocasek of the Cars. In addition to scoring a string of indelible new wave hits in the late ’70s and early ’80s, the frontman had previously worked in the studio with Bad Brains and Suicide, among other acts.

Wilson: To this day, the Cars’ first record is unimpeachable in every way.

Sullivan: I thought Ric would be a great idea because he’d produced some edgier bands that were coming out of left field. I sent Ric the demo and he responded immediately, kind of freaking out about the songs.

III. ‘A dark room by myself’

Ocasek, who died in 2019, had only one condition for taking the job, which was that Weezer come to him in his home base of New York because his wife, model Paulina Porizkova, was pregnant with the couple’s first son. They set up at the historic Electric Lady Studios in August 1993.

Cuomo: I was beside myself because I knew KISS had recorded there. I remember going to the bathroom for the first time thinking, Ace Frehley sat on this toilet that I’m about to sit on.

Sullivan: Ric was a real gentle guiding hand.

Cuomo: He’d sit in the chair with his knees folded up to his chest, like a giant stork. And he was constantly doodling these amazing psychedelic doodles.

Sharp: Paulina was there too. This is one of the most spectacular women in the world, and she’s not cheerleading us or anything. But by going about her business, it made you feel like it wasn’t crazy for you to be there — like, yeah, let’s get to work.

Among the songs Cuomo wrote after Ocasek agreed to produce Weezer’s debut were “In the Garage” and “Buddy Holly,” the latter of which Cuomo intended to save for the band’s second LP but which he included on the Blue Album at Ocasek’s urging.

Cuomo: For “In the Garage,” I definitely had the Beach Boys and “In My Room” in mind. At one point while I was writing, I wanted some new inspiration, so I went to Record Surplus on Santa Monica and went through all these classic LPs. I narrowed it down to “Led Zeppelin II” and the Beach Boys’ “Pet Sounds,” but I only had enough money for one. It was basically a coin toss, and I walked out with “Pet Sounds.” Then I went on a deep dive and got all their other albums. It’s funny that Weezer could’ve gone in a totally different direction.

In New York, the band’s members stayed at the rock-star-friendly Gramercy Park Hotel. Yet they hardly availed themselves of the city’s busy night life.

Wilson: I didn’t party between the ages of 20 and 30. So Matt and I stayed in. We were roommates, and I distinctly remember watching the first episode of Conan O’Brien’s show together. At the end, we were like, he just has to work on his s— a little bit and he’ll be great.

Cuomo: I was in the studio at least 12 hours a day — mostly in a dark room by myself.

Meanwhile, a fault line was deepening between Cropper and the rest of Weezer. (Cropper didn’t respond to The Times’ interview request.)

Wilson: Jason had a girlfriend and knocked her up, and she came to the sessions and the vibe was weird. It just wasn’t gonna work out. I remember sitting down and having the conversation with him. He was bummed, but I don’t think he was fully surprised.

Sharp: What it really boiled down to was that whatever it is we were setting out to do, it felt like it was gonna be much more difficult if he stayed. There’s a bunch of reasons for that, but they’re so boring that they’re not important.

Cuomo: We were pretty much done with the record.

Sharp: His departure happened the day we completed the first mix.

Cuomo: In our minds — these were mainly conversations between me and Matt — we felt like if this was gonna happen eventually, we wanted it to happen before the band was presented to the public. That way the fans would never have to deal with any kind of breakup. We all came from broken homes, and we wanted things to be very stable for the audience.

The Cars frontman, who died Sunday at age 75, crafted such perfect songs and eye-catching videos that the band’s hits have become rock classics.

Wilson: It was strangely anticlimactic. Really, we could have just been a trio at that point.

Sullivan: I think it was Rivers who called me, which was maybe a little odd, because normally it would’ve been Matt. He said, “We want to make a change on guitar.” For me, it was a panic, because I’m still a young A&R guy. How do I let the label know about this? Are we gonna have to re-record the whole record?

In fact, Cuomo rerecorded Cropper’s guitar parts in a single day.

Cuomo: Maybe I had to stop and fix an error or something. But I knew how the songs went. There are spots on the album where even now I really miss having him play those parts. The beginning of “My Name Is Jonas,” that’s pure Jason — he’s just like a hippie good ol’ boy. Or the finger-picking in “The World Has Turned.” I still sweat if I have to do those at an acoustic show.

Beyond the recording of the album, of course, Weezer would need to find a new second guitar player.

Sharp: We had one choice to replace Jason, and that was Brian Bell — which was ironic because we’d never seen or heard him play guitar. We’d only seen him play bass in a band called Carnival Art, and I thought, that is one debonair son of a bitch.

Wilson: I think Matt and Rivers just thought Brian looked great.

Bell: When they called, I had an instinct this is what was gonna happen. Matt was like, “Hey, what are you up to?” — just small talk. Then Rivers grabbed the phone: “Do you want to be in our band?”

Weezer overnighted a tape to Bell, who overdubbed himself playing on the band’s songs as a kind of audition, then sent the tape back to New York.

Bell: The very next day, someone from the record label brought me a plane ticket — this is back when they were a tangible thing on a thick-stock piece of paper — that said L.A. to New York. It was a red-eye, and when I landed there was a little man with a chauffeur hat and a long limousine with a phone in it. It felt so Led Zeppelin. We went straight to the hotel, and they told me I was gonna sleep in Pat’s room.

Wilson: Brian claims that when I met him, I dropped my pants. I don’t have a strong recollection of that, but I’m not ruling it out. It sounds like something I’d do.

At Electric Lady, Weezer played the almost-completed Blue Album for Bell, who’d arrived in time to contribute background vocals.

Bell: The first song they put on was “In the Garage.” It was incredible — like a lot of the indie stuff I was listening to, like Dinosaur Jr. and Pavement, but polished. I looked at them and said, “Guys, we’re gonna be f—ing huge.”

IV. ‘The right shade of blue’

With the group’s debut in the can, Weezer returned to L.A. in October 1993 determined to break in Bell as a full-fledged member of the band. Sharp leveraged his relationships with promoters around town to book what Weezer called the Self-Punishment Tour: a dozen shows in two weeks at venues including the Roxy, the Blue Saloon, Raji’s and the Alligator Lounge.

Sullivan: I sent a memo to the record company titled “Weezer Tours the Bowels of L.A.”

Sharp: Trial by fire, jump in the deep end — it was whatever cliché you want to use. But the thing is, I didn’t actually want anybody to see us yet, so I told the promoters, “Give me your worst slot — the 1 a.m. or the 6 p.m. or whatever. We’re just there to make mistakes.”

Sullivan: The gigs were very rough.

Rivers Cuomo opened the door to his home in Santa Monica and said he had something to show me.

Bell: My first show was at Club Lingerie, and I thought we were great. My parents came — it was a big moment. Afterwards, Rivers and I hugged for the first and last time. It was the most awkward thing in the world. I think I told him, “Don’t worry, that’ll never happen again.”

The band continued to hone its live attack in early 1994, though Cuomo also used the last of his money from Geffen’s advance to enroll in several music classes at Los Angeles Valley College, not far from the epicenter of January’s disastrous Northridge earthquake.

Cuomo: I remember feeling aftershocks in wind ensemble.

Bell: I had three jobs while we were waiting for the record to come out. I worked at Jet Rag, the clothing store on La Brea [Avenue]. I worked at Caioti, an Italian restaurant in Laurel Canyon — their claim to fame was they had this salad dressing that made pregnant women go into labor. And I delivered flowers.

While making a delivery one day to an office building, Bell was scouted by a casting agent working on a Nike commercial. She put him in the spot alongside a young Norman Reedus (later of “The Walking Dead”).

Bell: I told him about Weezer, and he goes, “Oh, sounds like kind of a Beck thing — like ‘Getting crazy with the Cheez Whiz’!”

Sharp: The album was pushed back so many times. I’d imagine we had the least amount of priority in Geffen Records history.

Yet the label hired the esteemed pin-up photographer Peter Gowland, who died in 2010, to shoot the Blue Album’s cover: Cuomo, Sharp, Bell and Wilson standing against a blue background.

Bell: We went to his house in the Palisades. I’d never even heard of the Palisades.

Cuomo: The night before, I went to some random salon and said, “Give me a haircut,” and that’s what they gave me. It totally sucks. But now that’s me for eternity in every meme.

Bell: I wore my favorite vintage bowling shirt. Pat came with his head shaved for some reason.

Cuomo: The original conception for the cover was that we’d be in these matching striped shirts like the Beach Boys.

Wilson: We played a show at Al’s Bar with Walt Mink and we wore the striped shirts. It bummed all the hipster bands out so hard.

Cuomo: I don’t know who suggested we do some shots in our regular clothes, but when we looked back at them, we all liked those the best.

Wilson: Coming out of hair bands into grunge, it just hit perfectly — like, oh, we’re normcore.

Spike Jonze (film and music video director): They looked like people I would’ve hung out with in high school.

Bell: We spent maybe two days searching for the right shade of blue.

Album cover in place, Weezer’s debut was almost ready for release.

Sharp: Right before it came out, Rivers and I sat on a couch with a yellow legal pad and calculated how many of our relatives would buy the record. I was like, “Put my dad down for one — actually, he’ll probably buy a few to give to people at his office.” I think we got up to 340 copies.

V. ‘We were trying to break this band’

The Blue Album finally dropped on May 10, 1994 — a month after the death of Nirvana’s Kurt Cobain and just weeks after DGC released “Live Through This” by Cobain widow Courtney Love’s band Hole.

Bell: We all wondered whether Kurt would’ve liked Weezer. That felt important.

Sullivan: There wasn’t a lot of love from the press. Because things didn’t happen in the normal quote-unquote alternative way — two indie records, tours all over — the reaction was that this was a manufactured band.

On Weezer’s new ‘OK Human,’ frontman Rivers Cuomo, aided by a 38-piece orchestra, set aside irony and artifice to craft a more inward-looking album.

Cuomo: You could easily be fooled: “Oh, these kids just picked up their instruments.” Somebody called us Stone Temple Pixies, which touched a nerve. To us, the music sounded amazing, so to have it dismissed like that was painful.

Sharp: I remember being in a record store not long after the album came out and seeing all the promo copies in the 99-cent bin.

Soon, though, “Undone — The Sweater Song” began to take off, first on college radio, then on trendsetting modern-rock stations like L.A.’s KROQ-FM and Seattle’s 107.7 The End.

Kevin Weatherly (program director, KROQ): It cut through because it was so different from everything else at the time. This was the height of grunge, and then along comes Weezer with this nerdy little pop-punk ditty.

Jonze: Matt called me and said the label really wanted to do a music video. But Rivers didn’t like the idea — he felt it was contrived. So we talked, and I told him, “Look, a music video can be anything. It doesn’t have to be what you think it is. It could be as perfect and simple as your album cover — just you guys playing against a blue wall, singing or half-singing or not singing at all.” He goes, “But then what happens?” And I’m like, “I don’t know — a bunch of dogs run through at the end?” I wasn’t pitching an idea as much as I was just saying that he could make anything out of it.

Sharp: We’d received video treatments from other directors and it’d be, like, the band enveloped in a giant sweater.

Jonze: That same day after our meeting, Matt called me again and said, “OK, Rivers wants to do the video you pitched.” I was like, “Wait, what video?”

With Jonze directing, Weezer shot the “Undone” clip in a studio in Silver Lake — dogs, blue wall, half-singing and all.

Jonze: We did a couple takes where they lip-synched all the way through. But I think we were more interested in just f—ing around. I was surprised by how compelling Rivers was. Even though I’d seen them live, I didn’t know he’d be so aware of the camera and how to play with it.

Bell: I’m not sure I was told the dogs were gonna come out.

“Undone” quickly found a home on MTV, which gave the video its coveted Buzz Clip status.

Patti Galluzzi (former vice president of programming, MTV): That was our way of saying that we were trying to break this band. And this was a textbook way to break a band: You start with a really catchy song, but it’s not necessarily what you think will be your massive hit. You do a video that shows a band in the way they want to portray themselves — that shows who they really are. That’s what comes across in the “Undone” video, so then you understand them before they come out in costume.

The costumes came in Jonze’s video for “Buddy Holly,” which depicted Weezer performing in a meticulous re-creation of Arnold’s Drive-In from the ’70s sitcom “Happy Days.”

Jonze: The way I come up with ideas for videos is I listen to a song over and over again and write down every idea I have — bad, good, stupid, whatever. With “Buddy Holly,” I just wrote “Happy Days” at some point. I was the right age where it was in reruns all the time, and I could just see the band playing in the diner. It also felt appropriate because they were referencing a lot of childhood things in their lyrics, and for the people that made “Happy Days,” the show was nostalgic for them.

Cuomo: Spike pitched it, and we were like, “Oh my God, the Fonz is gonna be dancing in our video.” It just blew our minds.

Bell: I walked onto the set and just thought, Are you f—ing kidding me?

In the video, Weezer’s performance is carefully intercut with clips from the original series, including Henry Winkler’s Fonzie doing his “Aaayyy” catchphrase. There’s also a newly shot cameo by actor Al Molinaro, who played the drive-in’s owner on “Happy Days” and who introduces “Kenosha, Wisconsin’s own Weezer.”

Jonze: It was 20 years later and he was very gray, so we put dye in his hair. A very simple trick, but it kind of blurred the lines even more. You’re like, Wait a second…

Wilson: I remember CNN doing a bit on it in the context of “Forrest Gump” and CGI. But even they missed it — there was no CGI in that video. It was all clever blocking and clever editing.

Legend has it that Nirvana’s ‘Nevermind’ and the grunge boom ended hair-metal careers and dominated popular music. An in-depth look back tells another story.

Jonze: Eric Zumbrunnen, the editor I worked with for almost 25 years — he passed away a few years ago — he and I sat and went through hours and hours and hours of “Happy Days” and assembled a skeleton that we were gonna drop all the shots of Weezer into.

Unlike “Undone,” “Buddy Holly” — which went on to win the prize for breakthrough video at the MTV Video Music Awards — featured Cuomo without the thick-framed glasses that had quickly become part of the frontman’s signature look.

Cuomo: That was very intentional, because I didn’t want to look too much like Kurt Cobain in Nirvana’s “In Bloom” video. I loved him so much, and I was so mad that I didn’t do that before he did it.

Wilson: I don’t know why Rivers’ glasses became a thing. I’m the guy who wears glasses — I’ve worn them since second grade! Later on, we’d go on some late-night show and Jordan Schur, the president of Geffen at the time, would be like, “Nah, man, you gotta wear the glasses.” Why did he have to wear the glasses?

“Buddy Holly” peaked at No. 2 on Billboard’s alternative rock radio chart in mid-December.

Galluzzi: We played the hell out of that video.

Weatherly: It all culminated with Weezer playing KROQ Acoustic Christmas at the end of ’94. We had Henry Winkler bring them onstage. That was great: Weezer and the Fonz hanging out at the Universal Amphitheatre.

Cuomo: I was so stressed out and scared.

VI. ‘I feel like I’m gonna pass out’

For all they did to boost Weezer’s profile, the band’s first two videos caused some to view the band as a bunch of ironic jokesters — a perception that Cuomo felt undercut the real emotional turmoil in his music.

Cuomo: That was quite a shock for me to discover that. It didn’t verify the great vision I wanted to have of us.

Bell: We were being called wisenheimers. I had to look that word up.

Toward the end of 1994, Weezer toured as an opening act for Live, the Pennsylvania alt-rock band then riding high with its album “Throwing Copper.”

Ed Kowalczyk (singer and guitarist, Live): After the shows we’d be running around drinking Jack Daniel’s and smoking cigarettes, and one night I walked onto Weezer’s bus and went to the back lounge. I’ll never forget it: There’s Rivers studying French and doing scales on his keyboard. I was like, this is a totally different band.

Weatherly: I don’t know if I’d say they were apologetic rock stars. But part of the charm was that they didn’t seem super-comfortable in the limelight.

At the same time, Weezer was happily toying with the kind of rock iconography Cuomo had grown up admiring in the likes of his beloved KISS.

Kowalczyk: No matter what size the venue was, they’d put this massive light-up W on stage behind them. This thing was probably 6½ feet tall, must have weighed 500 pounds. Three or four guys had to roll it in. Rivers and I are getting along great, and he’s like, “Come up and sing ‘Buddy Holly’ with me.” So I get up there one night — really small stage in a rock club somewhere — and those lights are so freakin’ hot I feel like I’m gonna pass out. This was the early ’90s — these weren’t LEDs, they were 200-watt fry bulbs like at McDonald’s. It turned the entire stage into an oven.

Weezer toured Europe for the first time in February 1995 as the Blue Album reached No. 16 on the Billboard 200. The LP’s third and final single, “Say It Ain’t So,” was accompanied by a video shot by director Sophie Muller in the garage at Weezer’s house on Amherst Avenue — the place Sharp had convinced the landlords to rent to the band three years before.

Cuomo: Looking back at it, it was this tiny little trashed guesthouse. But it was so huge for us. It’s gone now — they demolished it.

“Say It Ain’t So” draws on an incident from Cuomo’s adolescence when the sight of a beer in his family’s refrigerator led him to believe that his stepfather had become an alcoholic just as he thought his father had been. After the song came out, Cuomo heard from his dad.

Cuomo: I hadn’t spoken to him in years. I mean, I hardly spoke to him at all growing up. He only had a fax machine at the time, and out of the blue I got this fax from him: “Weezer, give me a call — we need to talk.” So I got in touch and explained where I was coming from in the song. But I’m kind of mortified that a lot of “Say It Ain’t So” — as powerful as it is and as true as it is — it’s based on a misunderstanding. The root of it is this photograph I have of my dad and my mom where he’s wearing a [sleeveless undershirt] and smoking a cigar and holding a Heineken. He looks so intimidating. My brother and I grew up looking at this photo, and somehow we got the idea in our head that he was an alcoholic and a violent guy and that’s why he left us. Years later, I was talking to my mom about it and she said, “He wasn’t an alcoholic. He didn’t even drink or smoke — he was like a Zen Buddhist guy. We were just goofing around in that picture. Those were just props.”

VII. ‘The guy loves to rock’

By the end of the summer of 1995, after a year and a half on the road, Cuomo had seriously burned out on touring and decided to leave music and enroll at Harvard. He also underwent a complicated medical procedure to lengthen one of his legs, which for much of his life had been shorter than the other.

Waronker: Going back to college and having an invasive leg surgery — that’s a weird reaction to success. But things were different, you know? Weezer was huge, and all of a sudden there were stakes and there was money and there were responsibilities. It wasn’t about going to the show and then hanging out after at a coffee shop anymore.

Sharp: Honestly, I was relieved. I had stuff I wanted to do outside the group — the Rentals and some other small collaborations with other people — and it had always been a scramble to wedge that stuff in whenever there was a break. There just weren’t that many breaks.

Weatherly: You didn’t know, when he went off to Harvard, was he gonna come back? Was Weezer still gonna be a band?

Bell: I never worried that it was done. Rivers was too motivated. It’s been proven that the guy loves to rock.

Indeed, Weezer returned just a year later with 1996’s “Pinkerton.” And a few years after that?

Cuomo: I think it was 1999 when my past as a metalhead was exposed. MTV News found my high school yearbook photo and all these fliers from my old bands. I was like, OK, the jig is up. I called Matt, who wasn’t even in Weezer at the time, but I knew he could relate to my pain. He made me feel a lot better. He just said, “Look, man, at this point it kind of comes off as cool — just go with it.” I guess enough years had passed. But if that had been ’94, it could have been a problem.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.