Lil Nas X came out, but has hip-hop? A macho culture faces a crossroads

- Share via

On June 30, the final day of Pride Month, the young country-rap sensation Lil Nas X came out to his 2.2 million Twitter followers.

“Some of y’all already know, some of y’all don’t care, some of y’all not gone fwm no more. but before this month ends i want y’all to listen closely to ‘c7osure’” he wrote, referring to a track from his debut EP “7,” then the No. 1 rap album in the country.

“Embracin’ this news I behold unfolding … I know it don’t feel like it’s time,” he raps. “But I look back at this moment, I’ll see that I’m fine.”

Overnight, the 20-year-old Atlanta native — born Montero Lamar Hill — became the biggest gay pop star in the world. That he did so in the orbit of hip-hop and country, genres that have historically snubbed queer artists, was groundbreaking.

“Lil Nas X re-imagined an image of the Wrangler-wearing, horseback-riding man’s man into a young black representative of youth culture, got the attention of two traditionally macho cultures and then came out on the last day of Pride,” said Roy Kinsey, a Chicago-based librarian and rapper at the forefront of Chicago’s queer rap scene. “It was genius.”

“It’s hard to be out in genres where being gay, or expressing your sexuality, is frowned upon,” added platinum rapper and singer iLoveMakonnen, born Makonnen Sheran, who rose to fame as a protégé of Drake and came out as gay in 2017. “We are finally starting to see queer black men celebrated in the genre. But this is still a genre that has never been supportive of change.”

Before the viral sensation of “Old Town Road” turned Hill into a pop star and gay icon, hip-hop was already reaching a turning point in its inclusivity, as more young black men exploring sexuality and interrogating masculinity in their work are getting mainstream attention.

“I feel like I’m opening the doors for more people,” Hill told the BBC recently. “That they feel more comfortable [being out]. Especially in the … hip-hop community. It’s still not accepted …” (Hill declined to offer further comment for this piece.)

Hip-hop’s refusal to embrace anything queer has been a blemish on the genre for as long as its been around. Rap culture has always been powered by unbridled machismo, and one would be hard pressed to not find a gay slur embedded in the lyrics of any of the genre’s most famous architects. In fact, an entire lexicon dedicated to pointing out discomfort with gay men has permeated rap lyrics. Slang such as “sus” and “No homo” and “Pause” that use queerness as a punchline have been thrown around casually for years.

But as the old guard has been replaced with a younger generation unconcerned with rigid labels and unbothered by genre, today’s rap and R&B scene isn’t as exclusively heteronormative as it once was.

“We know folks in our community have always been religiously conservative, and being gay is still seen as taboo,” said Ebro Darden, the global editorial head of hip-hop and R&B for Apple Music and host of “Ebro in the Morning” on New York’s Hot 97 radio station. “But with entertainment becoming more accepting, music is going to be right there. This moment isn’t some blip, because it’s not a blip in society.”

“I don’t have any secrets I need to keep anymore”

In 2012, avant-garde R&B-hip-hop singer Frank Ocean broke ground by boldly writing about falling in love with a man on the eve of releasing his breathlessly hyped debut album “Channel Orange.” “I don’t know what happens now, and that’s alrite. I don’t have any secrets I need kept anymore,” he wrote.

Ocean, who sprung from the rowdy, L.A.-based hip-hop collective Odd Future, went on to become a Grammy-winning star and in-demand collaborator for Jay-Z, ASAP Rocky and Travis Scott.

“Frank Ocean was the beginning of the revolution. But people had to warm up to it and sometimes the collective warm-up can take more time than we think,” said singer-songwriter Iman Jordan (Rihanna, “Empire”). “We’ve gotten used to seeing white queer men become megastars. I’m looking forward to the day when [more] black queer men are seen.”

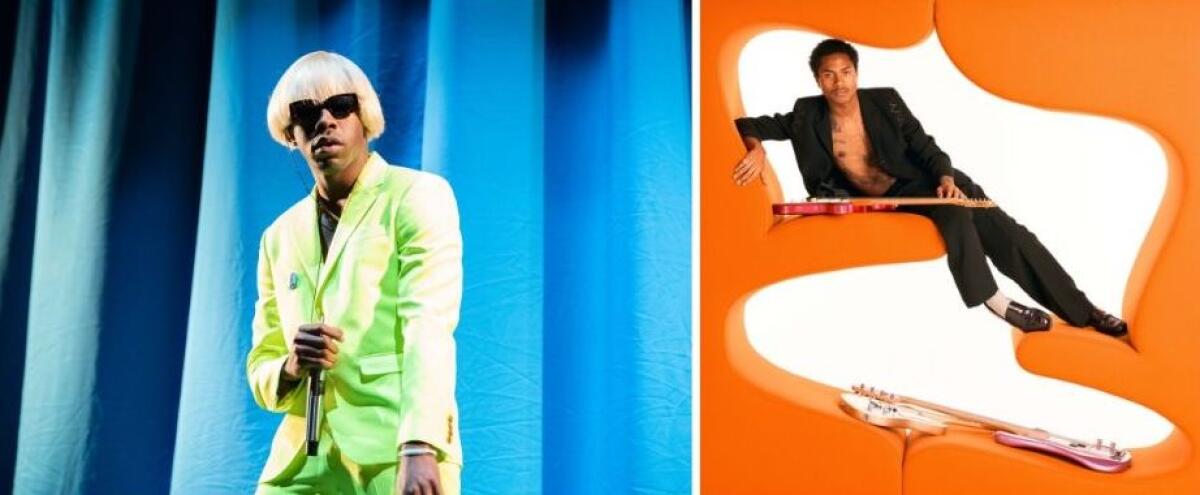

Over the past couple of years, Ocean’s former Odd Future collaborator, Tyler, the Creator, has transitioned from a bratty provocateur who hurled gay slurs with reckless abandon into a thoughtful confessionalist, one who surprisingly and rather matter-of-factly raps about his own attraction to men. His latest effort, “Igor,” is ostensibly a funky soap opera about a boy who loves a boy who loves a girl. “Take your mask off, I need her out the picture… Stop lyin’ to yourself, I know the real you,” he raps. “Igor” became the first Billboard No. 1 album of his career, and his most acclaimed.

A diverse array of talents such as Brockhampton frontman Kevin Abstract, Steve Lacy (also formerly affiliated with Odd Future) and Skype Williams have all presented works this year that are freely crafted through a black queer lens.

On his “Arizona Baby” album, co-produced by Jack Antonoff (Taylor Swift), Abstract reflects on growing up gay and in Corpus Christi at the turn of the millennium. “My ... back home ain’t even proud of me,” he raps on album opener “Big Wheels.” “They think I’m a bitch, just queerbaiting.”

And on his introspective new album, “Apollo XXI,” Lacy confronts his struggles to accept his bisexuality over groovy guitar riffs. “Coming into my understanding of my sexuality helped shaped the record to be carefree, human, fun and honest. I didn’t care to say I’m anything because straight artists don’t. This album represents sexual freedom and liberation for me,” Lacy told The Times earlier this year.

Big Freedia — the vibrant, gender non-confirming talent who put New Orleans bounce music on the map — has been called on by Drake and Beyoncé for hits. And a young black gay man has the No. 1 song in America and just eclipsed a chart record that Mariah Carey and Boyz II Men set 23 years ago with “One Sweet Day,” a song inspired by the AIDS crisis and the tragic peril it brought to so many black gay men in this country. (“Despacito” by Luis Fonsi, Daddy Yankee and Justin Bieber had shared the record.)

While queer female performers such as Janelle Monae, Halsey, Young M.A. and Kehlani have been accepted with little fuss, there’s now a growing surge of queer black male voices that are cutting through a genre built on heteronormative ideals.

“[Black] queer women are having a better time than men right now, creatively,” says New York-based DJ, producer and rapper Skype Williams. “But male representation is moving in the right direction,” he continued. “The catalyst for this shift though? I think when people in political power are [threatening] our basic rights, art and music gets more interesting.”

It helps that the streaming era has disrupted how stars are created. Artists are no longer beholden to an ecosystem ruled by gatekeepers and pop music has gotten far less homogenized.

No genre of music offers better proof of this than hip-hop, where Generation Z rap stars are born on Soundcloud and TikTok and not radio. “Old Town Road” was a meme on TikTok — a popular lip-sync social media app —well before it was the inescapable radio earworm that reignited old debates about race and genre.

Furthermore, artists are playing to a generation far more open-minded and permissive when it comes to gender and sexuality than their older millennial counterparts. A report by trend forecasting agency J. Walter Thompson Innovation Group back in 2016 found that only 48% of 13-20 year-olds identified as exclusively heterosexual, compared to 65% of the generation before them.

This is an audience that shrugs when Tyler, the Creator does an about-face the way he did on 2017’s stellar “Flower Boy” where he casually rapped about being attracted to men after years of using gay slurs — a topic he still refuses to address outside of the music (he declined to be interviewed for this piece). “Truth is, since a youth kid, thought it was a phase / thought it’d be like the phrase; ‘poof,’ gone / But, it’s still goin’ on,” he rapped.

And that’s not to say the rest of the music industry is that much further ahead.

Pop music had lacked an openly gay superstar before Adam Lambert and Sam Smith made history with their chart debuts and Grammy victories, respectively. And despite their statuses as legendary rock hitmakers and gay icons, there was much hand-wringing over how biopics for Queen and Elton John would handle the queerness of its subjects.

The evolution in hip-hop is significant, albeit more gradual and less pronounced than the larger shift in pop culture over representations of black male queerness.

There was Fox’s hip-hop drama “Empire,” which made a powerful statement by making one of its leads a gay black R&B singer (for a time, the records released by the character — played by Jussie Smollett — were the only music by an out gay black man getting mainstream radio play.)

“Moonlight,” a coming of age tale about a gay black boy, won best picture at the Academy Awards in 2017 and for the first time queer people of color outnumbered their white counterparts on TV, according to GLAAD’s annual TV diversity report. Series such as “Queen Sugar,” “Dear White People” and “This Is Us” feature storylines abound nuanced black LGBTQ characters; meanwhile, Ryan Murphy’s “Pose,” which has exposed the world to a part of black queer culture that has inspired pop divas for decades, is up for two Emmys, including one for Billy Porter, the first openly gay black man to receive a lead actor nod. And a quarter-century after “you better work,” RuPaul has turned drag into a multi-million-dollar empire.

But is all this enough to swing the pendulum toward permanent change in R&B and hip-hop?

A long history of homophobia

Since the genre’s dawning , nearly five decades ago, homophobic attitudes in hip-hop have been the norm. N.W.A and the Beastie Boys boasted about their disdain for gay people in lyrics. 50 Cent once said it wasn’t OK for men to be gay, but women who like women? “That’s cool.”

Nicki Minaj incited her sizable queer fanbase by using a gay slur on her latest album. The late XXXTentacion was as famous for his contemplative music as the violent mythology he constructed to sell it — including gleefully boasting about beating a man within an inch of life because he looked at him too long. Just last year, Migos’ Offset notoriously rapped, “I cannot vibe with queers.” And Eminem has yet to retire his usage of “faggot” in the 18 years since he famously performed with Elton John at the Grammys as a PR-orchestrated act of good will against his viciously homophobic lyrics.

“The sport of hip-hop is very masculine and macho,” says iLoveMakonnen. “The industry is full of queer black men and yet some of hip-hop loudest voices won’t speak up and support us because they don’t want a target on their back. How can we get the acceptance of people who haven’t even accepted themselves? So much of gay culture is influencing the world, including hip-hop, and yet the culture is ashamed of us.”

Despite being on the cutting edge of setting trends, queer black folks are still last in line when it comes to representation across a mainstream pop culture zeitgeist heavily informed by black queer creatives. From fashion to music to the English lexicon, black queer people have set the pace even if they don’t always, in turn, see themselves embraced.

A wave of black queer rap artists, including Le1f, Zebra Katz, Cakes Da Killa, Mykki Blanco and House of LaDosha, broke out of New York at the start of the decade with music and visuals that upended the very same gender constructs that have been weaponized against gay men for the last century by pairing hyper-feminine aesthetics — high fashion looks, weave, manicured fingertips — with braggadocios’ rhymes. They proved that men in baggy jeans and fitted caps weren’t the only ones with biting flows and, yes, queens could do it better. (Note: The preceding video contains strong language.)

But the wave of New York queer rap and the coming out of Ocean and iLoveMakonnen, for many, felt like false starts. Queer rappers hardly got the attention needed to break into mainstream consciousness and if they did, they most certainly were never men — a reminder that a divide still remains on acceptance. There’s limits on how queer black men can be seen, and the line is sex.

“Black male images are often connected to the sex he has — how many women he can acquire, his virility,” said Roy Kinsey. “And rap caters to that image. As a queer man, I have to constantly wonder if people will be more or less likely to buy my record if they knew how [I had sex].”

Just a few weeks ago, New Orleans rapper Young KSB went viral with a gloriously raunchy ode to anilingus that’s as sexually explicit as anything dominating Spotify playlists — but it’s impossible to imagine that viralness transitioning to the mainstream.

Even as Hill was celebrated for breaking rap’s gay glass ceiling, the jokes about his sex life also made it into the news coverage. When asked about Hill’s coming out, Young Thug — a rapper who jumped on an “Old Town Road” remix and has toyed with gender norms by dressing in couture gowns — said that Hill “probably shouldn’t have told the world” he was gay.

“It ain’t even about the music no more. Soon as the song comes on, everybody’s like, ‘This gay ass ... [Dudes] don’t even care to listen to the song no more,” Thug said during an interview with hip-hop influencer Adam 22. “Just to certain people. He’s young and backlash can come behind anything.”

Thug isn’t entirely off-base. While queer representation has improved, there’s still a calculation being made by artists. How many acts who get mainstream attention are as sexually explicit as their straight counterparts? And how many approach discussing their sexuality in the media with the same transparency as their personalities suggest?

“I wasn’t ready to test the waters back then, even with the support of my label,” said Jordan, who is releasing his first EP since coming out in 2016 and exiting his former label Interscope. “I felt constant pressure to be more macho and fit in by not being too feminine or differently dressed. The optimist in me sees Lil Nas X as an example of mainstream acceptance. But on the other hand, he came out after already having a No. 1, and I do wonder if coming out before he was famous would’ve changed his trajectory.”

“Artists don’t want to become a spokesperson, or be seen as a gimmick,” says Darden. “Especially when it relates to their sexuality. It’s still their life.”

Williams’ debut EP, “Sorry I’m Late,” a sizzling collection of boom-bap rap, syrupy pop and soulful funk released independently last month, is a bright mediation on living and dating in New York City. It’s just one in a string of recent releases from young black men rapping and singing about love, and sex, between two men with straightforward transparency.

Describing the inspiration behind “Sorry I’m Late,” he declared that “work made by gay people doesn’t necessarily need to be like Troye-Sivan-twink-lily-white-lithe-pastel-pink-pop .. but it doesn’t have to be turbo-homo-DL-thug [stuff], either,” a snipe at the realities that face black queer artists when trying to get their music heard.

“It’s easy to digest non-threatening, flaming, skinny gay men. It’s as simple as that,” said Williams. “Some people have a hard time imagining anyone ‘other’ being complex.”

Hip-hop is at its queerest right now. Whether or not that moves beyond this moment is yet to be seen.

“The labels are being supportive of our art,” says iLoveMakonnen. “Now, it’s on listeners and the media to keep embracing us.”

Warning: Some of the songs below contain explicit material

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.