- Share via

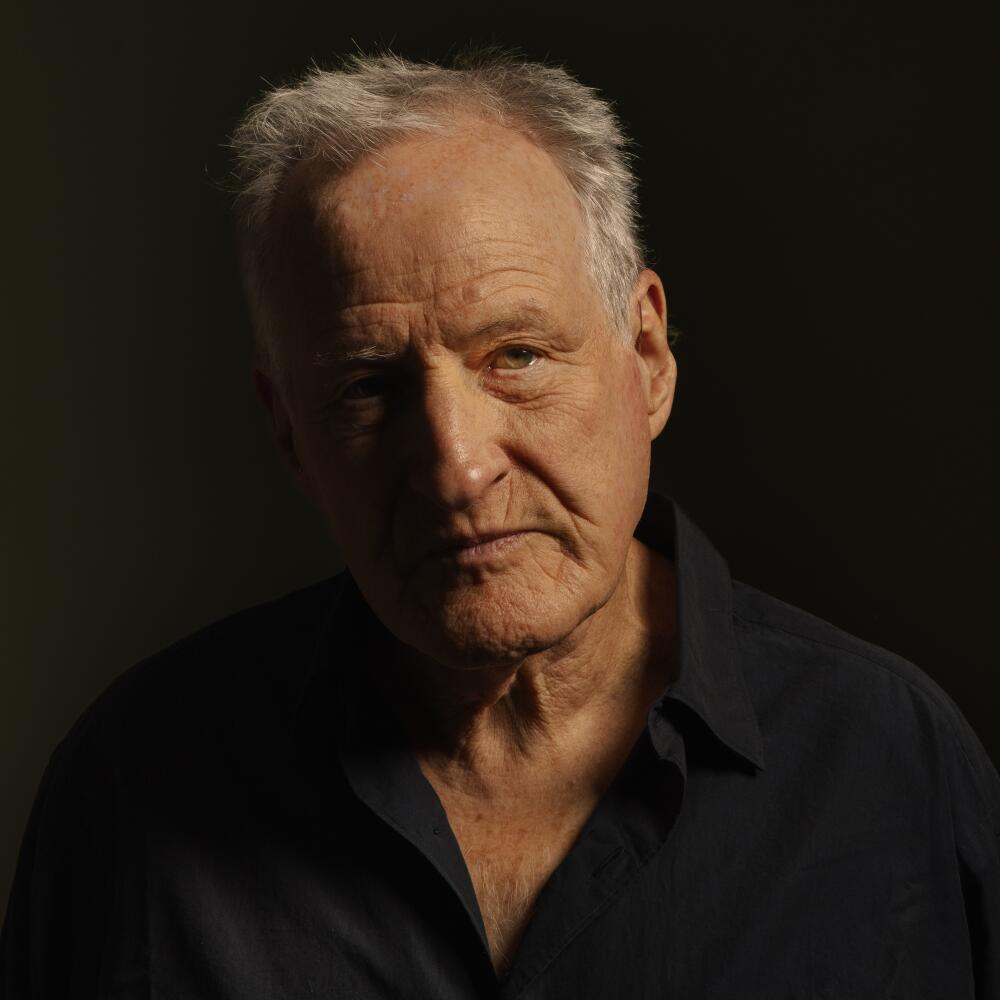

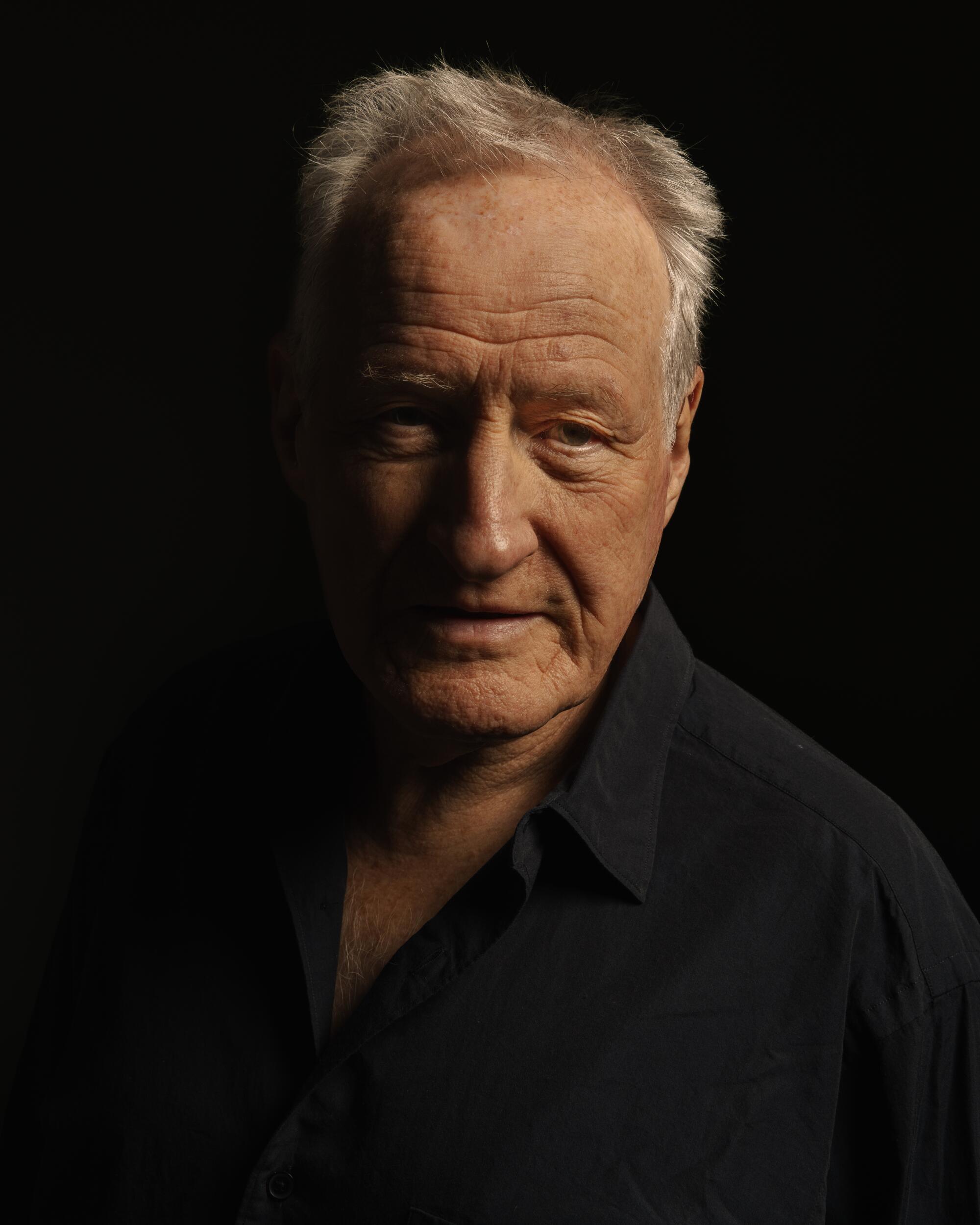

Michael Mann is a filmmaker known for his exacting, obsessive attention to detail. Enzo Ferrari was an automaker who many would describe the same way.

And yet, in the decades it took for Mann to develop and finally make “Ferrari” — which details an especially pivotal chapter of Enzo Ferrari’s life over a turbulent few months in 1957 — the director says he was never drawn to the story for how it reminded him of himself.

“I really don’t see myself in Enzo,” says Mann, 80, during a recent video interview. “First of all, I don’t go looking just for characters within whom I can find myself. So I don’t do that search in the first place. I’m not really interested in myself. I’m not that self-reflective.”

But there were elements that spoke deeply to him. “The challenge was very exciting to me,” Mann says, “to create life as it was in Italy, in Modena in 1957, and not just the material, like the facades of buildings and wardrobe and decor and the factory, but the sociology, the psychology, the emotionality.”

‘Tis the season for much more than gift exchanges, cocktail parties and cozy sweaters: The holidays bring with them a bumper crop of films and TV shows, and The Times is here as your guide. Through Sunday, we’re covering the key titles to watch this season, from late-breaking Oscar contenders and acclaimed TV dramas to holiday classics old and new. Hot cocoa sold separately.

The film follows Ferrari (Adam Driver), on the crest of 60, as he struggles to keep his company financially afloat while preparing his racing team for the arduous Mille Miglia race, while also juggling difficulties with his wife Laura (Penélope Cruz) as they suffer through the emotional fallout of the death of their son Dino the year before. Secretly, Enzo also has a young son, Piero, with another woman, Lina Lardi (Shailene Woodley), and must decide whether the boy will eventually take his last name.

“I remember my father as my father,” says Piero Ferrari, now vice-chairman of Ferrari, during a recent call from the company’s historic headquarters in Maranello, Italy. “My father was a person who was always looking ahead, moving forward, never going back.” He feels that Driver has captured something true to that drive and determination.

“You can say you like the movie or not, but the story in this case is a real story — it’s really what happened,” says Ferrari.

That sense of detailed authenticity is Mann’s stock-in-trade. The moody existentialism of his work, which includes “Thief,” “Manhunter,” “The Last of the Mohicans,” “Heat,” “The Insider,” “Miami Vice” and others, has only grown in popularity since the release of Mann’s previous feature, 2015’s “Blackhat.” A sense of fandom and fervor around the director has never been higher, with a younger generation of movie fans attaching itself to his genre reinventions, impeccable craft and philosophical explorations of masculinity.

Mann’s professional connection to Ferrari cars goes back to the original “Miami Vice” television show in the mid-1980s, on which he was an executive producer. (The Daytona Spyder and Testarossa featured on the show are among the most iconic cars in TV history.) The Chicago-born director also raced Ferraris for a time — “I couldn’t race consistently enough to get good,” Mann says — and figures he has owned from six to eight of the cars over the years.

The hyperfocus required of driving a high-performance car has some similarities to making movies with the level of exactitude demanded by Mann. But it also expands even beyond that.

“You do have that unity and you’re in kind of a harmonic state with a car,” says Mann. “You and the car become one organism. And you’re not present in the moment. You’re always projecting yourself into the future. You’re not aware of where you are. You’re focused on what you’re going to do next. Then the next thing just kind of happens, it’s gotten from ideation to fact. And that’s obviously an advanced state of performance.

“And I think there is a connection between that mentality and a universal human impulse to exceed whatever the current limits are,” says Mann, “to go farther, go faster, to excel beyond the last stage we were personally at as individuals in any and every endeavor. It’s why we run, it’s why we paint pictures, it’s why we go to the moon. It is a real universal human impulse.”

Mann is speaking from his longtime offices on the edge of Santa Monica, not far from his home. He first started keeping offices on that side of town when he was making “Heat” in the early 1990s and didn’t want to commute to the Warner Bros. lot in Burbank.

“I’ve just always wanted to be about eight minutes, nine minutes from where I live, because I work very erratic hours,” says Mann. “I could get up at three in the morning or on the weekend, suddenly decide I want to do something in editing and go there. So proximity’s real important.” (The image of someone heading to work in the middle of the night is straight out of a Michael Mann film.)

On a wall over his shoulder behind him is the famous photograph of Che Guevara, inscribed and given to Mann personally by artist Alberto Korda. (Mann also has the original contact sheet from which the image was chosen.) That sense of being both an insider and an outsider, making a film about an Italian auto industrialist under the gaze of a Cuban revolutionary, is part of what gives Mann’s work its combustible energy.

“I remember him saying it’s hard not to get philosophical about an engine, because it is a metaphor for a lot of things,” says Driver, recalling a visit to the Ferrari factory with Mann just weeks before shooting. “It’s like a million parts that have to move in perfect synchronicity and perfect timing for it to function. And the minute one piece is off, the whole thing collapses. It’s very much a metaphor for making films.”

Driver describes working with Mann as a submersion into technical mastery, though not without its moments of invention. “He does a lot of research, he’s a deep dive, but he is very open on the day to being surprised, which I think is not talked about enough,” the actor says. “His preparation is very extensive, obviously, and that’s exactly who you want watching a monitor, watching your performance and giving you his opinion about the movie he’s trying to make. But he is very impromptu at the same time.”

Shooting in Modena, Italy, where the Ferrari family lived meant that the research process never stopped. Cruz read love letters between Enzo and Laura Ferrari provided by the family doctor, and learned to cook some of the same dishes as Laura, even though they are not in the movie. For all their discontented men, Mann’s films have also often acknowledged the impact on the women in their lives, memorably with Tuesday Weld in “Thief” or Diane Venora in “Heat.” But the attention he pays to Cruz’s Laura in “Ferrari” (a performance of rage and unexpected humor that’s already getting awards buzz) pushes him further than ever.

“I realized that Michael really had a mission with this character in terms of paying homage to all the women with similar life situations, women living in the shadow of men, especially in those times,” Cruz says. “But what is kind of beautiful and funny is that Michael would not put that into words. But deep in his heart, he did this because he needed to.”

She recalls the smile on Mann’s face as he pored over ledgers and journals kept by Enzo Ferrari that detailed every minute piece of his cars and every moment of countless auto races.

“It’s so amazing to have somebody that can give so much and expect the same from you and from every member of the crew,” she says. “For me, that’s never too much.”

“Ferrari,” with a reported budget of $95 million, was financed independently by a patchwork of sources. It is the highest budgeted film ever released by Neon, the distribution company behind “Parasite,” “Spencer” and “Anatomy of a Fall.”

“It was a very difficult film to get launched,” Mann says, noting that with creative freedom came even greater responsibilities and risks. “That’s both a great way to make a movie and not a great way to make a movie.”

With a script credited to screenwriter Troy Kennedy Martin, who died in 2009, “Ferrari” allowed Mann to both further explore and expand on some of his ongoing themes.

“First of all, the absolute operatic melodrama of everything that was really going on in actuality in his life in those four months of 1957,” said Mann. “The wonderful contradictions, the unpredictability, he’s such a unique character. And it’s at such a radical divergence from the stoic image of that immobile face with the sunglasses.

“The duality of the guy. I think that’s what really got me,” adds Mann. “It’s so filled with the way we really are. We have all kinds of things in opposition within us. We’re internally in conflict. We’re in conflict with things in our environment and our circumstances within ourselves and our marriage. And most of these conflicts only resolve in motion pictures. They do not resolve in real life. They don’t resolve — we go to our grave with them.”

Mann adapted those tensions to the style of the film itself. While his films of late — from “Collateral” and “Public Enemies” to “Blackhat” — have committed to the jagged textures of digital filmmaking in a way that sometimes verged on experimental, “Ferrari” sees him returning to an almost classical feel, more composed in its imagemaking and cutting, especially the scenes of Enzo with his family.

“To me there is an artistic strategy about the narrative that I feel is my obligation to have,” explains Mann. “And for this one, so much of the story is the melodrama — it’s not drama, it’s melodrama — the larger-than-life passions, the sensuality that’s going on with these people and what they’re confronting. And that I decided it should be somewhat static in rooms.”

He still moves his camera around, sinuously but never distractingly. “I want to be seeing the faces and I want to hear the dialogue,” Mann says. “That generates the crises that are occurring in these lives. The resolution is the physical action of the racing.”

Indeed, the driving sequences in “Ferrari” are another matter, thrilling and terrifying in equal measure, building to the startling depiction of the horrific crash during the 1957 Mille Miglia that killed 11 people. Mann estimates a total of $6 million was spent just on building cars for the movie.

“I wanted to put you in the driver’s seat,” he says. “I wanted you to experience the savage beauty of these powerful machines as if you were in the shoes and looking through the eyes and feeling with your hands on the steering wheel what these drivers are. I wanted all that to be experiential.”

For Mann, it’s less about why than how. He says he rarely questions the root of his attraction to cars, the solitary driver and the twin momentums of fate and purpose.

“I think I’m attracted to people who are struggling to do something, to accomplish something,” he says. “And like all of us, I’m probably my own harshest critic, and I drive myself forward. I think characters who are conscious, are struggling to be conscious, are self-aware, want something, are pursuing something — they interest me.”

Mann is now turning his focus to adapting his first novel, the 2022 bestseller “Heat 2,” co-written with Meg Gardiner, into a film for Warner Bros. The story follows the characters of “Heat” both before and after the events of the original 1995 movie. Mann admits he could have made it for a streaming service and the structure of the story would make it easy to split into two films, but he resisted the urge. “I want it to be one hopefully important film of some scale,” he says.

“Ferrari” finds him still very much with his foot on the gas, even if the recent, ruminative epics of Martin Scorsese (only a few months older) offer him a point of comparison to his own restless ferocity.

“That’s probably because Marty’s more mature than I am,” Mann offers with a laugh. However, it’s a conversation he says he has had many times with his good friend, the 86-year-old architect Renzo Piano. Are they supposed to take it easy, or at the very least stop to consider all they have accomplished? Or should they be more like Enzo Ferrari with that racer’s philosophy of pushing ever onward?

“You just keep going,” says Mann. “You want to love what you do, and you keep doing it. Until you can’t.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.