- Share via

Just over a decade ago while in her mid-20s, British actress Rebecca Hall started to unpack the legacy of her biracial roots.

Hall — who presents as white — is the daughter of the opera singer Maria Ewing, a fair-skinned biracial woman and the late theater director Peter Hall. Her maternal grandfather, a light-skinned Black man who married a Dutch woman and raised his kids white, was also white-passing.

For the record:

4:51 p.m. Jan. 29, 2021An earlier version of this post incorrectly said Rebecca Hall identifies as white.

“I began to think about how racial passing is representative of the American dream, in the sense that you can be self-made and turn yourself into something else, but also representative of the lie at the center of the American dream, which is that you only get to [participate] if your complexion is a certain color,” said Hall. “And as I started thinking more about that, I started wanting to know more and see how I sit in relation to that.”

A friend recommended she read “Passing,” Nella Larsen’s 1929 novella examining the fluidity of racial identity as it pertains to two light-skinned Black women living in New York amid the Harlem renaissance. She didn’t yet know the material would lead to her feature directorial debut, which premieres at the Sundance Film Festival this weekend.

Hall says she was “viscerally gut-punched” by Larsen’s book. “I found it to be such a staggering work of literature and so startlingly modern,” she said. “Here is a woman writing about racism in America not through acts of white oppression as dramatic set pieces but about the things one internalizes through living within a racist society. I found it startling that she’s also using it as a metaphor for the complexity that is at the center of how we form our identity.”

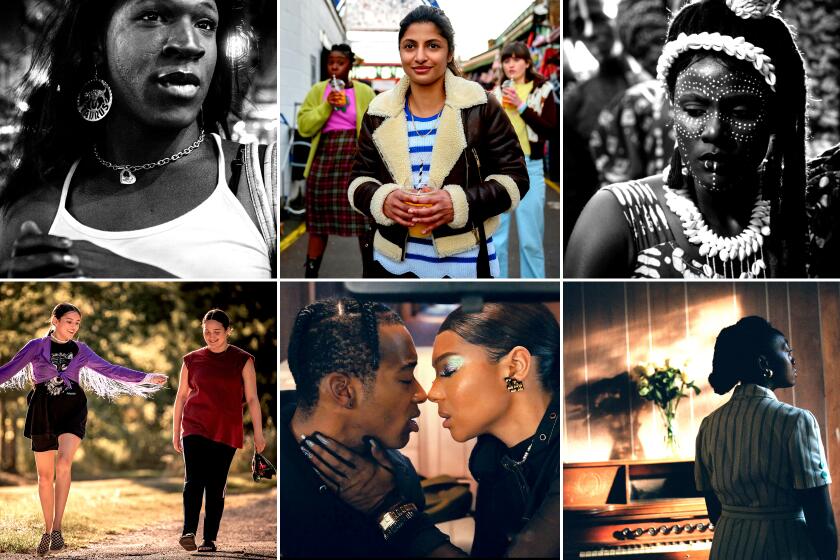

The book centers on the friendship between Irene (played in the film by Tessa Thompson) and Clare (Ruth Negga), childhood friends who reconnect during a chance encounter at a ritzy whites-only hotel. It is Irene’s first attempt at passing, while Clare has made a lifestyle of it, even marrying an unsuspecting wealthy racist (Alexander Skarsgard) who affectionately calls her “Nig.” “It’s a book where very little happens, and yet how it interacts with your mind is enormous,” said Hall. “And it affected me so profoundly: I recognized these women. I understood them.”

She began adapting the story into a script immediately and wrote the first draft in 10 days “and then rapidly put it in a drawer and thought, Well that’s crazy. No one’s ever going to let me make that.

“I had this fantasy about making a 4:3-aspect-ratio, Academy standard-looking noir centering faces that didn’t get to have those films made about them at the time,” she said. “I had a very precise understanding of how I wanted the film to feel and the tone of it, but it also felt completely crazy to me at the time. So I wrote other things and pretended I was going to make them instead, and yet I kept coming back to this one.”

Trying to get the film made was “a long road” with multiple false starts. “It’s been difficult to make movies about women and even more difficult to make movies about women of color,” said Hall. “When I first started showing people the script, it was, ‘This is great but you know it’s going to be very hard to get made.’ And I’d be like, ‘Why?’ And there wasn’t really an answer.”

In 2018 she teamed up with producing parters Nina Yang Bongiovi and Forest Whitaker, whose company Significant Productions helped launch the first features of Ryan Coogler, Chloé Zhao and Boots Riley.

“I was a little hesitant because what we do as a production company is champion filmmakers of color,” said Bongiovi. “Our mission is to lift up underrepresented voices. So I told her, ‘I don’t know if it’s right for a Caucasian woman to tell a story about Black women who can pass. And when she told me that her [maternal side of the family] is African American but have been passing for generations, I almost fell off my chair. I was like, Wow, this actually makes her such a perfect filmmaker to tell the story.”

From there, one major challenge still remained: getting the clearance to shoot in black and white. “Black and white is not an easy thing to get financed at the best of times, but I was very bullish about that,” said Hall. “It felt like the most interesting way to make a movie about colorism was to take all the color out of it and be in a symbolic environment where you’re already thinking about how important those categorizations are. It’s not actually black and white, it’s gray. And I didn’t want to cast actors purely because of their capacity to pass for white; I wanted to cast the right people.”

While doing press for the Sundance-launched bio-pic “Christine” in 2016, Hall kept running into Negga, who was doing a simultaneous press run for “Loving” (the true story of an interracial couple that would ultimately earn Negga an Oscar nomination for lead actress). Hall gave Negga a copy of the script and her choice of the two leads. “We took a meeting after she read the script and she said, ‘You’ve got to let me play Clare,’” Hall remembered.

“I just found Clare so beguiling, quite mysterious and full of these massive, lovely contradictions,” said Negga. “I thought [the story] was such a brilliant evocation of why people pass, and in Clare you can very much see in her backstory and her history why she felt that was in many ways the only option. I was so struck by the amount of energy it must have taken to keep this huge secret.”

A wide range of narrative and documentaries highlights to watch for at the first virtual Sundance Film Festival.

Shortly after, Hall approached Thompson for the role of Irene. “I was astounded by how haunted I was by Nella Larsen’s words and world, I truly couldn’t shake either,” said Thompson by email from the set of Marvel’s “Thor: Love and Thunder.” “Because the book is so intimately from Irene’s perspective, the world of the material was incredibly intertwined with the character for me. Then I read Rebecca’s screenplay and was wowed by how she communicated the themes of the book with such economy and clarity.

“I have not gotten to play a character as undone by her thoughts as Irene, and it seemed like a terrifying challenge. I do sometimes live in my head, so I felt an utter compassion for Irene. And I really wanted to be directed by Rebecca, who is one of the finest actors around.”

Hall credits the actresses’ “tenacity and loyalty” as a big turning point in getting the film made. “When it was clear there were people who trusted my vision who are respected and brilliant, things started to move,” she said. “And then I had to get as many other famous people as I could in it. But [Ruth and Tessa] were real champions of it and stood behind it for a long time.”

While Thompson has never considered herself as able to pass, she says the themes of the film hit home for her particularly in relation to her experiences in the film industry. “I believe I am very clearly a woman of color,” she said. “I do however know that I have a certain measure of privilege because of my light skin. That is something I am continuously unpacking, especially working in Hollywood.”

“What’s interesting about this book is that we’re all so very much affected by how other people see us or perceive us,” said Negga. “I think when you’re a kid it’s very hard to understand the impact it has on you. For me, I felt like it was very important not to be treated like flotsam and jetsam on somebody else’s wave of interpretation of who I am. And it was very important for me to seek identity in art and literature. I think it spurred my interest in the arts because I think that’s where we see ourselves reflected.”

Under the umbrella of race and colorism, “Passing” deals with themes of sexuality, class, motherhood and the performative aspects of femininity. “‘Passing’ to me is as much about ‘passing’ for any of the norms, and I think the book is talking about the performance of gender and sexuality to be sure,” said Thompson. “Relationships are so complicated, it’s impossible to parcel out exactly why we are drawn to each other.”

“I think sexual undertones exist in so many relationships; it’s just that we don’t really talk about them,” Negga agreed. “And now that sexuality is being acknowledged as being more fluid and talked about in less restrictive terms, I think we’re acknowledging what has always been there. There are levels of attraction in relationships that are not black and white.”

With the exception of films like 1959’s “Imitation of Life” and 1949’s “Pinky,” the film presents a rare examination of colorism and an even rarer depiction of white-passing characters not portrayed by white actors. “The film history of it feels like it’s a white gaze-y fascination with people who look white but actually are not, and that’s kind of racist,” said Hall. “I don’t think there’s been a film that actually deals with it as sophisticatedly as the book does, and I felt that there was a huge gap there.”

Today, passing has become an antiquated notion, while blackfishing, or attempting to pass for Black, is much more common in popular culture and on social media. “I believe Blackness is one of America’s most popular exports,” said Thompson. “Blackness has never not been en vogue or commodified. For me, what feels more interesting is to talk about Blackness independent of whiteness. Blackness on its own terms for its own sake.”

Sundance’s Tabitha Jackson won the festival director gig, then the pandemic hit. How she’s leading the film festival’s 2021 edition into the future at a pivotal time in history.

“Blackfishing has been around since the minstrel days,” said Negga. “It’s not really a new phenomenon, but I think people are calling it out for what it is more and more. I don’t think a lot of people are very aware of the damage it can do and the duplicity of it. But now there is a stage set to talk about these things, and society is confronting it and looking at what we digest, how we digest it and who we’re digesting it from.”

More than 90 years after the book was first published, Hall says Larsen’s story feels as relevant as ever. “What’s interesting about the book is that it’s also about this precise time in America, and there are some echoes in this moment to that moment in history,” she said. “We’re in a time of enormous upheaval, potential economic crisis and huge social unrest.”

“I think any time would have been right [for this story], but now whether by their own volition or because there’s pressure, [Hollywood’s] gaze is looking towards Black film, literature, music and art,” said Negga. “It’s a renaissance. And I think it’s wonderful that there’s going to be a spotlight on this film, whereas before maybe there wouldn’t have been.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.