- Share via

Michael Le had prepared months for this moment — and it wasn’t going well.

The TikTok star, who built a huge following with his viral choreographed dance moves, found himself barely hanging on in the second round of a live-streamed boxing match at Hard Rock Stadium in Miami Gardens, Fla.

Le was trapped in a corner of the ring, struggling to fend off a barrage of punishing punches from his opponent, British YouTuber Jarvis Khattri.

With only one of his prescription contacts remaining, Le didn’t see Khattri’s right cross punch. He fell backward and his head slammed against the ropes, as his body slid to the ground.

“Boom! Lights out,” a commentator yelled. Memes proliferated online celebrating the knockout punch.

“I was like, bro, three months all being down to this,” Le said in a YouTube video posted days after the fight. “I was extremely pissed.”

TikTok, a popular based social video app owned by China-based ByteDance, has seen explosive growth this year amid the coronavirus crisis. The company has plans to hire more people, including at its Culver City office.

Le was down, but not out. Despite the humiliating defeat in June, months later the Los Angeles resident began training for his next fight. Why would this 21-year-old multimillionaire — who is among TikTok’s most popular creators with nearly 52 million followers — subject himself to such punishment?

The answer says as much about Le’s pride as it does about the growing — and unlikely — confluence between the worlds of boxing and influencers.

Le is part of a crop of social media stars hoping to boost their fandom and pounce on the $438.6 million U.S. boxing events industry, according to market research firm IBISWorld.

- Share via

Influencers are training to participate in amateur boxing matches in a bid to gain more attention and fans.

In the last decade, the number of people who make money as a “creator” — a person who creates video, photo or digital content primarily on social media — has grown to more than 50 million people worldwide, including 2 million who do it as a full-time job, according to data released in 2020 by San Francisco venture capital firm SignalFire.

But gaining new fans for creators or influencers has become increasingly challenging, as the once-nascent social media platforms have now grown to massive, global video libraries where it’s difficult to stand out from the crowd.

That’s where boxing comes in. Boxing tournaments can draw thousands of viewers, exposing influencers to a new audience that could help increase their earnings — based primarily on their followers on apps such as TikTok, Instagram and YouTube, which in turn amp up the advertising and brand deals they make.

“There’s just way more of them, so it’s harder for creators and influencers to get those eyeballs because there’s so much competition,” said Jesse Saivar, chair of law firm Greenberg Glusker’s intellectual property and digital media and technology groups. “They’re trying to get as many eyeballs as possible and boxing has been a good source of that.”

What began as a marketing gimmick appears to be gaining traction. LiveOne, the Beverly Hills-based entertainment company that live streamed the Social Gloves match between Le and Khattri, says the one-day event that featured multiple stars from YouTube and TikTok generated more than $12 million in revenue.

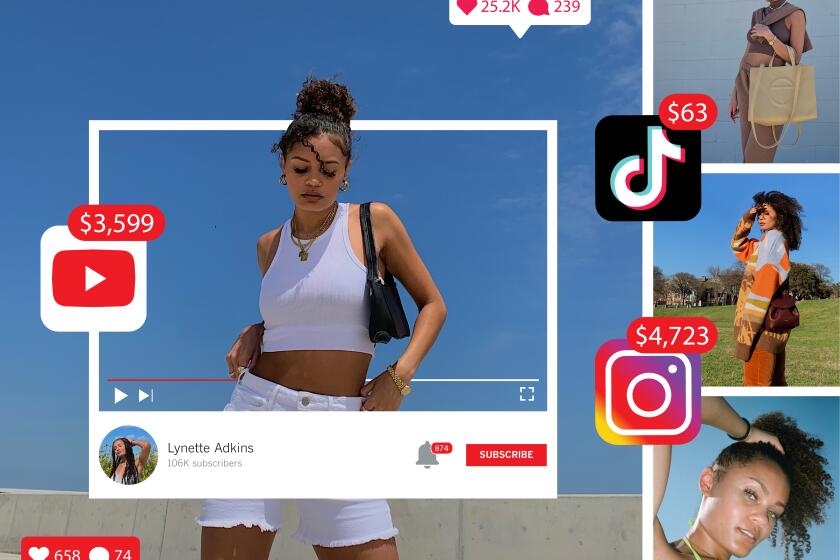

Meet Lynette Adkins. She’s part of a new crop of creators focusing their content on the how-to of the business: making money from an online following.

Despite a legal dispute with the organizers behind Social Gloves — which also sparked claims from Le and others over unpaid fees — LiveOne plans to stream several other similar events. The company says 70 influencers have expressed interest in participating.

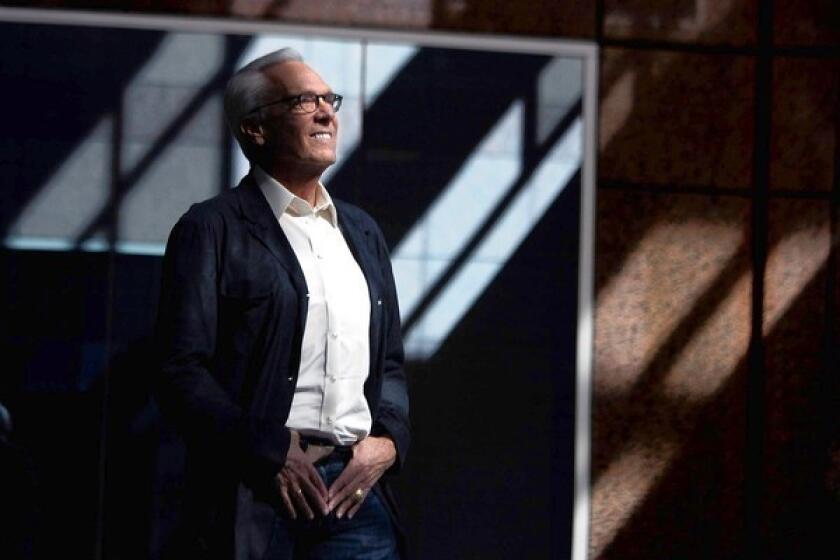

“It’s WrestleMania meets Disney,” LiveOne CEO Robert Ellin said. “There have been so many superstars that have come out of wrestling, who have driven brands, became movie stars, became pop stars. You’re going to have this great trend now of social media stars that are going to want to get across this entire environment of fighting, athleticism and driving their brand in this fashion.”

Many were inspired after watching YouTuber Logan Paul fight Floyd Mayweather Jr. last year. (ESPN deemed Mayweather the winner).

“That is insane — Logan Paul going from no boxing experience to fighting one of the best fighters in the world,” said Jaden Sprinz, a 24-year-old Arizona influencer who has taken up boxing. “It was like, ‘Wow.’ It kind of showed me that anything’s possible.”

For their part, boxing promoters are embracing such fights, viewing them as a way to connect their sport with younger audiences who don’t watch cable TV.

“It was almost inevitable that social media stars would break into sports,” Showtime Sports President Stephen Espinoza told The Times last year. “Celebrity today clearly means something very different than years before.”

A novice in the ring

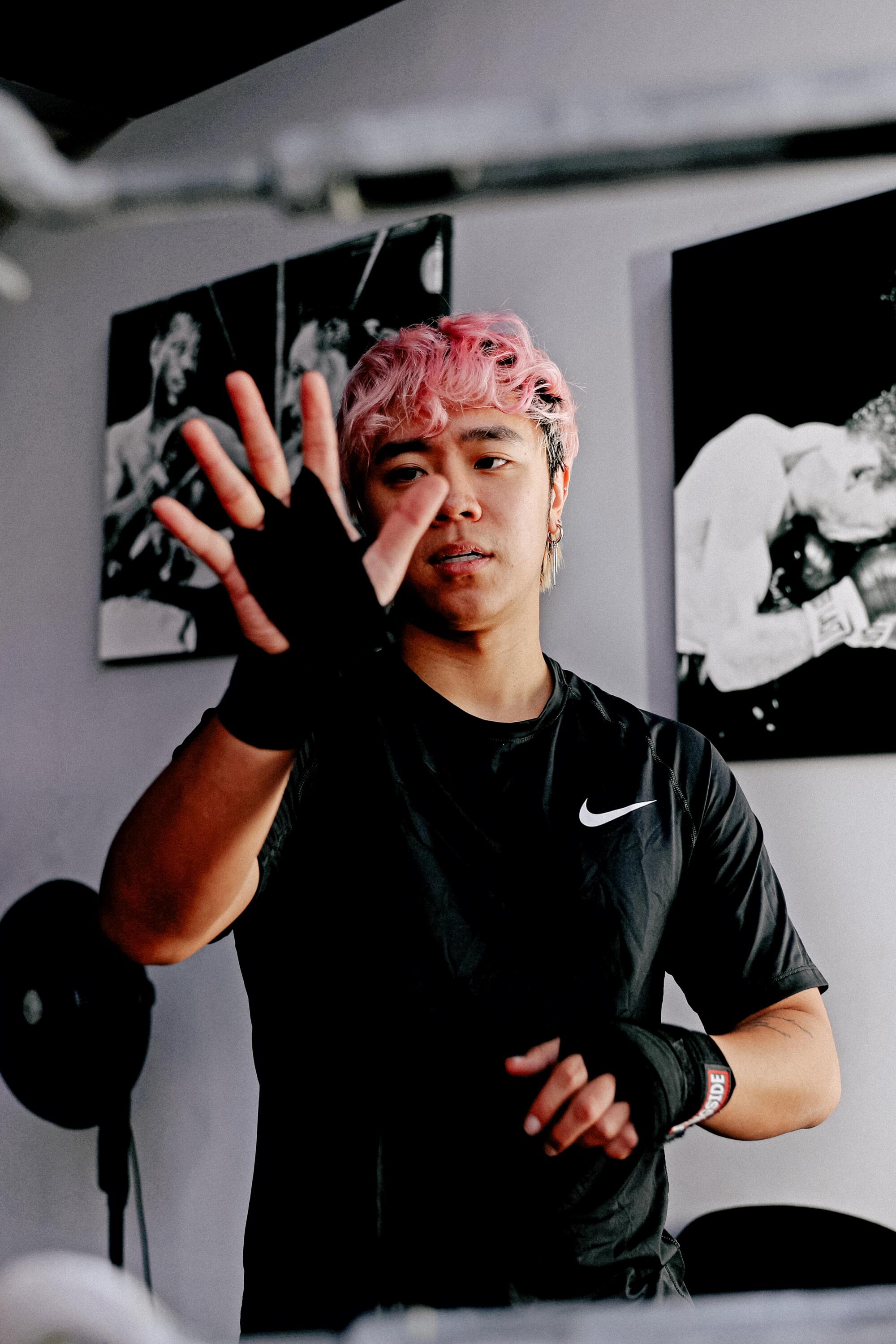

On a recent Friday afternoon, Le donned boxing gloves and practiced punches at a Studio City gym. Sparring with his coach Ricky “Showtime” Quiles, the pink-haired influencer worked on his jabs and uppercuts beside a backdrop photo of Sugar Ray Robinson and other boxing champions.

Le delivered 12 uppercut punches, swinging his right fist into Quiles’ boxing glove.

“Like that, like that,” Quiles said, a four-time championship prize fighter and boxing trainer. “The goal is to have it in your muscle memory,” Le said. “It’s like once you enter the ring, you forget a lot of it. A lot of it gets thrown out the window.”

Le, who had no prior boxing experience before committing to his first match, is no stranger to learning footwork and combinations.

He fell in love with dance after taking a class at 12 years old, and propelled it into a career as an instructor in his hometown of West Palm Beach, Fla. Then, in 2015, he decided to build up his social media profile.

“I told myself, ‘OK, it’s not a matter of how, it’s a matter of when’ ... and ‘I know I can do it,’” Le said.

Popular Asian American comedic video creators like Ryan Higa and Kevin Wu inspired him, showing a different way to make a living, said Le, who is Vietnamese American.

“I’ve always personally been very entrepreneurial-minded, and never really felt like I wanted to do a 9 to 5 for the rest of my life,” Le said.

Meet Lynette Adkins. She’s part of a new crop of creators focusing their content on the how-to of the business: making money from an online following.

Out of his family’s garage, Le uploaded dance tutorials on social media, like how to do the Nae Nae, a hip-hop dance move, in reverse. His popularity skyrocketed after he ramped up his video content on burgeoning social media app TikTok in 2019.

Le’s clip of him dancing inside his local Walmart store stood out in a sea of lip-synching videos and went viral. His followers grew from 600,000 to 1 million in just one week.

“That was just unheard of,” Le said. “So I was just super stoked and I just kind of like fell in love with the app and just kept going.”

Le, whose social media username is “justmaiko” (which he says is “just an Asian way of spelling Michael”), eventually amassed 51.5 million followers on TikTok, with videos capturing pranks, smooth dance moves, his life and interests.

He became a full-time video creator, and in 2020, moved his family from West Palm Beach to Los Angeles. His sister Tiffany and mom Tina both featured on Le’s videos, also have gained millions of social media followers.

As Le’s fan base grew, so did his income. Last year, he says he made more than $3 million, primarily by promoting brands such as streaming service Disney+, clothing sold on Amazon and teeth straightener Invisalign. He recently made his first film appearance, a cameo in the blockbuster “Spider-Man: No Way Home,” and is represented by major talent agency WME.

Forbes ranked Le as the sixth highest-earning TikTok star in 2020. He’s the 14th most popular video creator on TikTok based on number of followers, according to analytics firm Social Blade.

But Le knows there is no guarantee those fans will stay with him or if the platforms where he uploads his videos will continue to exist or alter their business practices.

Which is why boxing deals can be so attractive, generating potentially hundreds of thousands of dollars for each participant. YouTuber Jake Paul has a multi-fight deal with Showtime Sports. Forbes estimated Paul made $40 million from his three boxing wins last year.

So last year when YouTuber Austin McBroom came to Le’s home explaining his vision for “Social Gloves” — an amateur boxing match that would pit popular TikTok stars against their YouTube rivals — Le quickly signed up.

“I was really looking for something to boost my brand and get my name out there even more,” Le said. “With my social media ... I’ve always wanted to break the barrier, the boundaries of what I can and can’t do, and I saw this was a cool opportunity to be like, ‘Oh cool, you can do other things as well.’”

Le, with no prior experience in boxing, found his trainer a month and a half before the tournament. That didn’t leave much time for Quiles to shape him into a boxing champion.

L.A.’s TikTok creators earn thousands of dollars a month. Trump’s threat of a potential ban has them concerned.

“He was like a blank piece of paper,” Quiles said. “I’m like Michelangelo, and we both started creating our work together. So I started from scratch with him and taught him good boxing technique.”

By that, Quiles, a 51-year-old former professional boxer, means teaching Le how to do “slick s—.”

“Make a mess. Make them pay,” Quiles said. “Defense. Offense. All the jabbing, moving your head, being really slick.”

Le said over the course of his training, he lost 10 pounds and gained that back in muscle. He boxed in the morning for an hour, ran two miles during the day and at night worked out for another three or four hours. He consumed 150 to 180 grams of protein a day.

“It was like rinse, repeat, basically,” Le said.

Quiles, who has worked with celebrities like actor David Arquette, said he previously had no idea who Le was or the magnitude of his fame.

“At first I was like, this is kind of weird,” said Quiles, of the influencer boxing trend. “But you know, anything that’s positive out there, if they train hard and have deep respect to the sport, which they do, especially after a fight ... I think it’s pretty cool.”

And humbling.

When the Social Gloves tournament launched in June, Le was considered the underdog. His opponent, Khattri, weighed in 5.6 pounds more than the 145.6-pound Le. But Le had more social clout — at the time he had 48.6 million TikTok followers compared with Jarvis’ 4.57 million YouTube subscribers.

“I felt like I was going to be ready for it because I’ve done professional dancing so being onstage and performing for an audience isn’t something that is new to me ... but once I was at the ring, it was completely different,” Le said. “Your endurance is completely like wiped away just because of all the adrenaline is pumping because of the audience.”

Last fall, TikTok faced a number of problems and seemed to be on the ropes. Now, the app has bounced back.

Le’s knockout, along with other scenes from Social Gloves, went viral. LiveOne said Social Gloves collected more than 3.5 billion impressions across social media, the press and event platforms.

“Influence is what fame means today,” said Kyle Hjelmeseth, president of G&B, a firm that manages digital talent, in an email. “People will tune into a ‘typical’ celeb athletes vs. influencer boxing fight because the power of social media drives our economy, develops trends, drives retail sales, and now, as you are seeing, drives sports.”

But last summer’s sporting spectacle also gained notoriety over accusations that Social Gloves failed to pay some of the fighters.

Le said in a court filing that Palmdale-based Simply Greatness Productions (SGP), which is associated with YouTuber Austin McBroom, reneged on a commitment to pay him $400,000, and instead only paid him a $25,000 signing bonus.

LiveOne also sued SGP, saying the event wasn’t properly marketed. SGP countered that LiveOne withheld financial information. The case was settled.

Attorneys representing Le and SGP declined to comment on the litigation.

Despite the legal fight with Social Gloves — and losing to Khattri — Le hasn’t thrown in the towel yet.

There was an upside to his loss: Since that match, he’s already picked up 2.9 million more followers on TikTok.

At the Studio City gym, after punching through several workout sets to improve his agility and stamina, Le leaned against the sides of the ring, saying he was tired and sore. Then, he got back up.

“My boxing story isn’t finished yet,” he said.

His punching gloves compete with his many other projects, such as promoting NFTs or nonfungible tokens, another trend TikTok creators have embraced.

“Boxing has opened my eyes to a brand new sport that is super dope that I have a new appreciation for,” he said. “This is definitely not going to be the last time people see me breaking out of my box and my bubble.”

L.A.-based live music video streaming service LiveXLive said it plans to acquire PodcastOne, a Beverly Hills-based podcast production company. The all-stock transaction is the latest sign of growth in the podcast industry.

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.