This writer loves feminist ‘art monsters’ — but thinks ‘cancel culture is destructive’

- Share via

On the Shelf

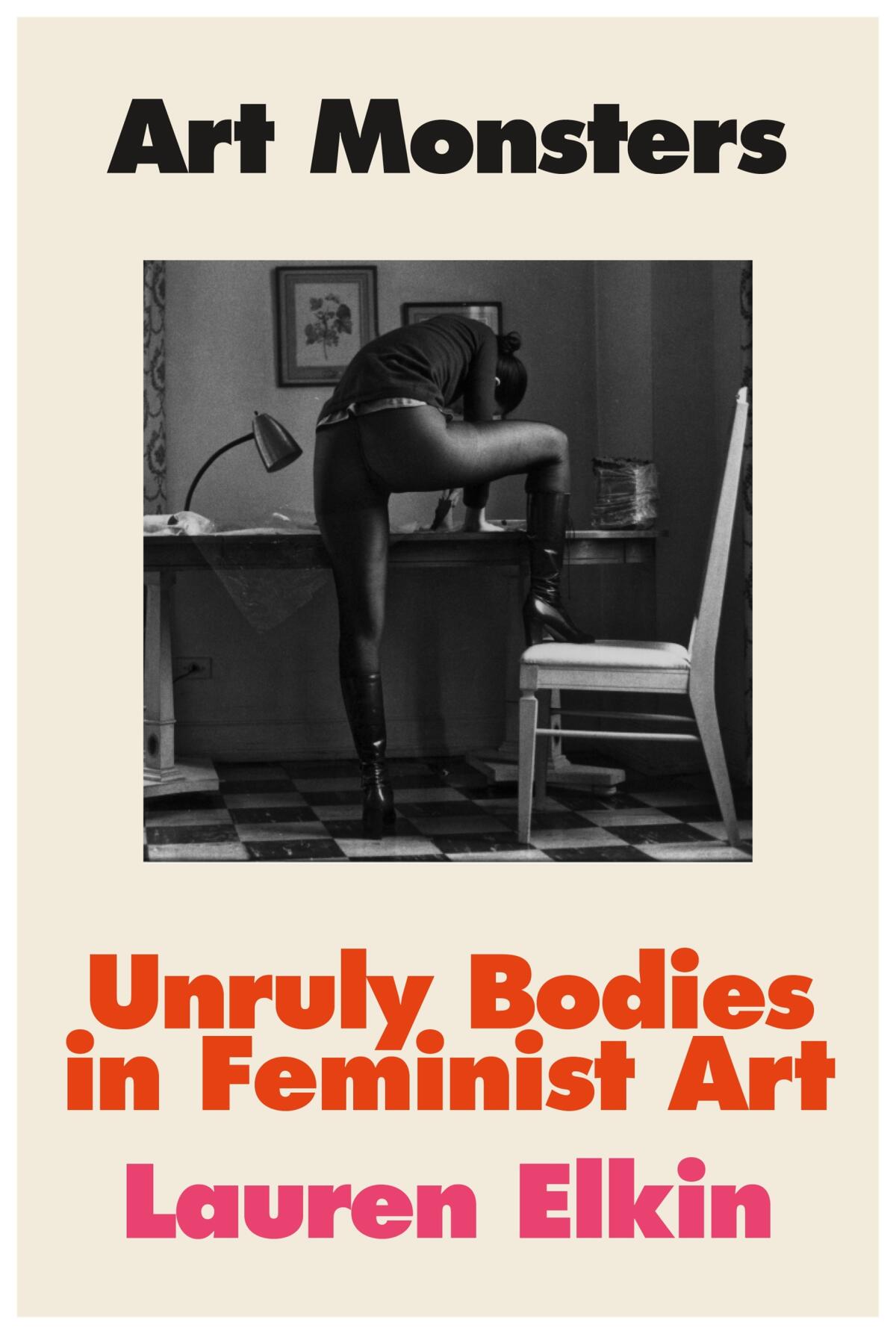

Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art

By Lauren Elkin

FSG: 368 pages, $35

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

There came a point when Lauren Elkin realized her book-in-progress was becoming a blob. As the writer Chris Kraus defines it: “the book as Blob, swallowing and engorging … Unwise and unstoppable.” Elkin introduces “Art Monsters,” a book about “unruly bodies in feminist art” with an epigraph from Virginia Woolf, reflecting that the adventure of “telling the truth about my own experiences as a body” is, for her, still unrealized. That is the driving force of this book — what unites all the monsters within it.

Approaching my conversation with Elkin, which was held over video chat from her home in London, I wondered what to ask her about. Kara Walker’s sugar sphinx? The controversy surrounding Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till, “Open Casket”? What Carolee Schneemann pulling a scroll out of her vagina had to do with “Three Guineas,” Woolf’s 1938 indictment of the connection between patriarchy and fascism?

Elkin’s own experience as a body is also in play. “I’m sure if this book had been written before the pandemic, pre-motherhood, it would be a completely different book,” Elkin said. “But then I thought, why am I trying to make a book about monstrous art into some obedient, traditional little book?” Elkin spoke to The Times in a conversation edited for length and clarity.

Claire Dederer, author of ‘Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma,’ explains why she went beyond bad men to probe our history with all artists who defy moral expectations

Can you say a bit about how you came to write this book?

I started writing it for real in 2017. My PhD advisor, Jane Marcus, died. She’s responsible for changing the way we read Woolf, in the States at least — from this snobby upper-crust crazy lady to this radical pacifist and socialist. I wanted my next book to play into this legacy.

I’m not a joiner; I see my writing and my teaching as my activism. The whole book was going to be about Woolf’s “Three Guineas” — I had in mind that I wanted to write a war book about Woolf. But I felt like I wasn’t done writing about women in public space. I was writing toward that.

I was shocked to learn that Woolf’s close friends and family didn’t like “Three Guineas.” They didn’t think she should be writing such an “angry” book about war.

Yes, E.M. Forster infamously said after Woolf died that feminism was a blight on her work. That her writing was so beautiful, her prose was such an achievement, and that her writing about feminism and pacifism and politics in general were “spots” on her greater contribution to literature.

Many of the artists you cover are grappling with war, from Woolf to Schneemann, who created work about Vietnam, and Martha Rosler, who collaged magazine spreads together with war photos. It made me think of Sylvia Plath, who was accused of antisemitism for appropriating Jewish identity and the Holocaust in her poem, “Daddy.”

As a Jewish woman, I have never read that poem as antisemitic. If anything, I’m grateful to Plath for drawing attention to the horrors of the Holocaust. It is an appropriation, but she’s using it as a metaphor. It is cringey, for sure, to see her compare herself to a Jew. But that was some of what I was trying to do with this book — it’s called “Art Monsters,” by the way, not “rah rah, amazing art heroines!” Some of these artists are monstrous; certainly the art is monstrous because it forces us to go places that are out of our comfort zone.

As editor and annotator of this new edition, Merve Emre leads the reader to a new understanding of ‘Mrs. Dalloway.’

In your discussion of a recent controversy in the art world, Dana Schutz’s painting of Emmett Till, “Open Casket,” you say you agree it should have been destroyed. This surprised me. Why do you think so?

It isn’t as if Dana Schutz is painting herself as Till, but she is making a portrait of him in his casket with no awareness of her whiteness or of the gaze. I think it is problematic for an artist to be lazy about looking. Till’s casket had a sheet of glass laid over it, so in all of the photographs taken, you can see the reflection of the people looking down at his body. Without that gaze, or interest in looking, that’s a problem. As a white woman, perhaps, her place is to be thinking about whiteness. When you have people saying this artwork traumatizes me, it hurts me, and it’s not generating a conversation, then you have to wonder: What is its purpose?

You write jubilantly about the artists you love, but so many of those in your book died horrific, tragic deaths. Eva Hesse of a brain tumor at age 34, Hannah Wilke of lymphoma at 52, Helen Chadwick of a heart attack at 42. Ana Mendieta was murdered when she was 36; Theresa Hak Kyung Cha was raped and murdered at 31. How is this possible?

I asked myself this question so many times while I was writing this book. I wasn’t trying to find women who have come to bad ends. I think, obviously, racism and misogyny kill women. They still do. Even though this is a group of women from all different backgrounds, racism and misogyny, even in medicine ... these things kill women.

Do you think recent “cancellations” of iconic male artists have opened up a space for audiences to be more engaged with the work of women artists, and artists of color?

I’m not a fan of cancel culture. It shoots down interesting people without describing what you mean by calling something or someone “problematic.” These should be teachable moments rather than just throwing the art and the artist away. For instance, why does it make me cringe when Plath calls herself a Jew in “Daddy”?

Perhaps it has opened up more space for artists who are underrepresented, but cancel culture is destructive to art. It’s really up to the consumer of the art. You have to ask yourself, what am I getting from this? If Kathy Acker’s “Pussy, King of the Pirates” gives you more sustenance than Jonathan Franzen’s “The Corrections,” then go to “Pussy.”

In ‘The Baby on the Fire Escape: Creativity, Motherhood, and the Mind-Baby Problem,’ Julie Phillips looks to 20th century artist-mothers for answers.

Perhaps this is an annoying question, but do you think you would’ve written this book had you not become a mother?

I don’t think this is an annoying question at all. I don’t see why we can’t talk about this. Though we need to ask men this too. It would be a totally different book. The connection to the body that so many of these artists are working through ... if I hadn’t become pregnant when I was working on this proposal, or experienced childbirth or early motherhood, it would’ve been completely intellectualized. Now I know what the monstrosity of the body is.

Can you be an art monster if you’re a parent?

I think you certainly can create monstrous art, and art in general, if you are a parent — with the right support and under the right conditions. Perhaps you can’t be an art monster, but you can create monstrous art. Anyway, I hope so.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.