Playwright August Wilson was ahead of his time. But would he have made it today?

- Share via

Review

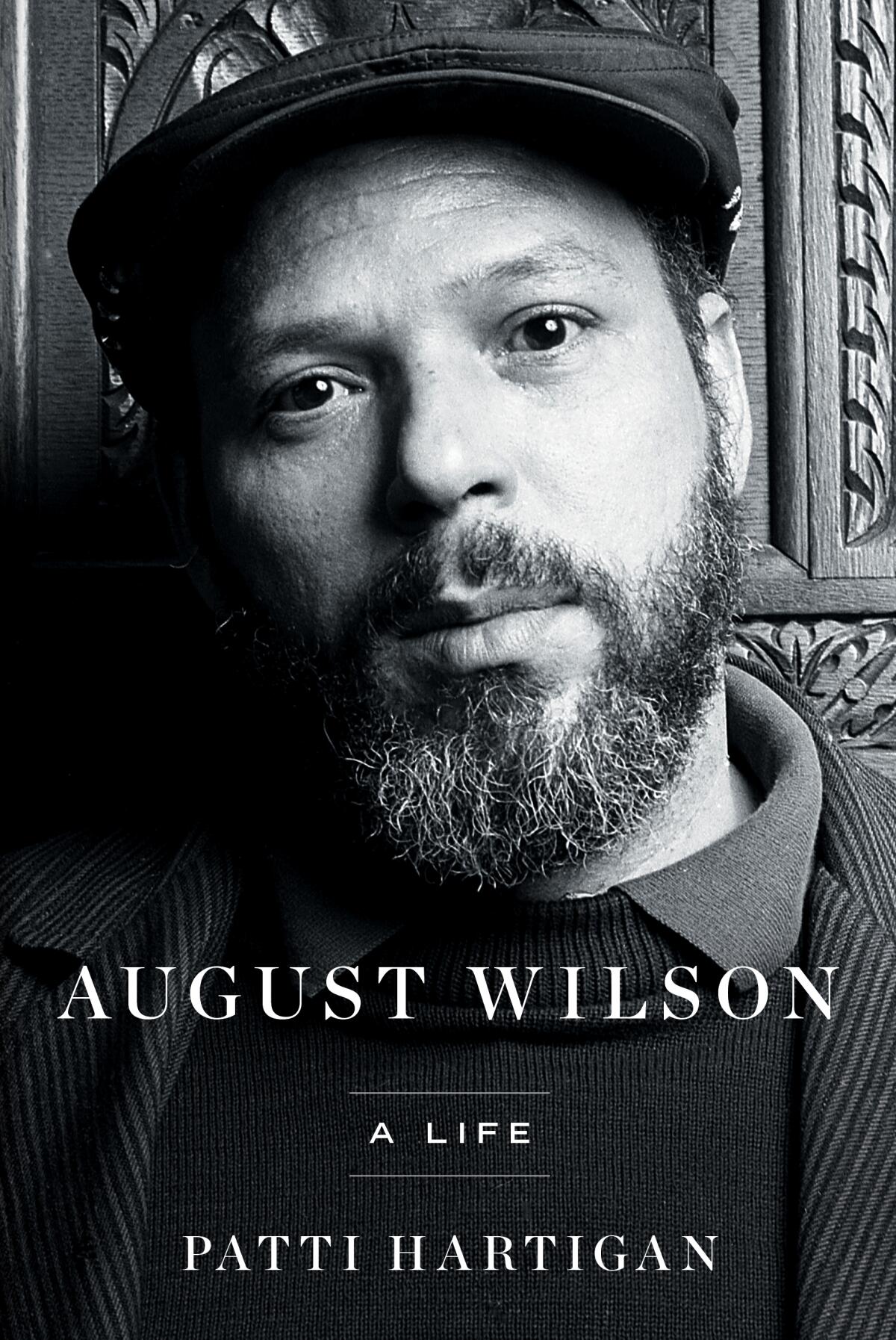

August Wilson: A Life

By Patti Hartigan

Simon & Schuster: 544 pages, $32.50

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

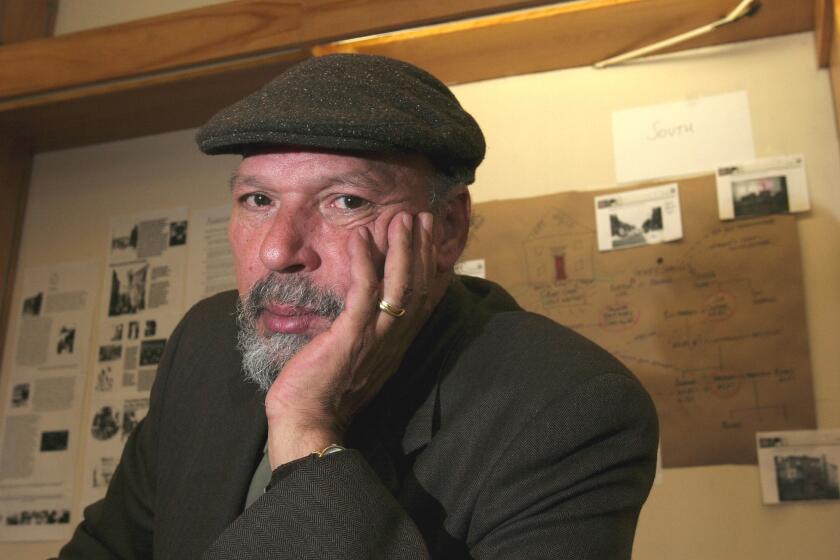

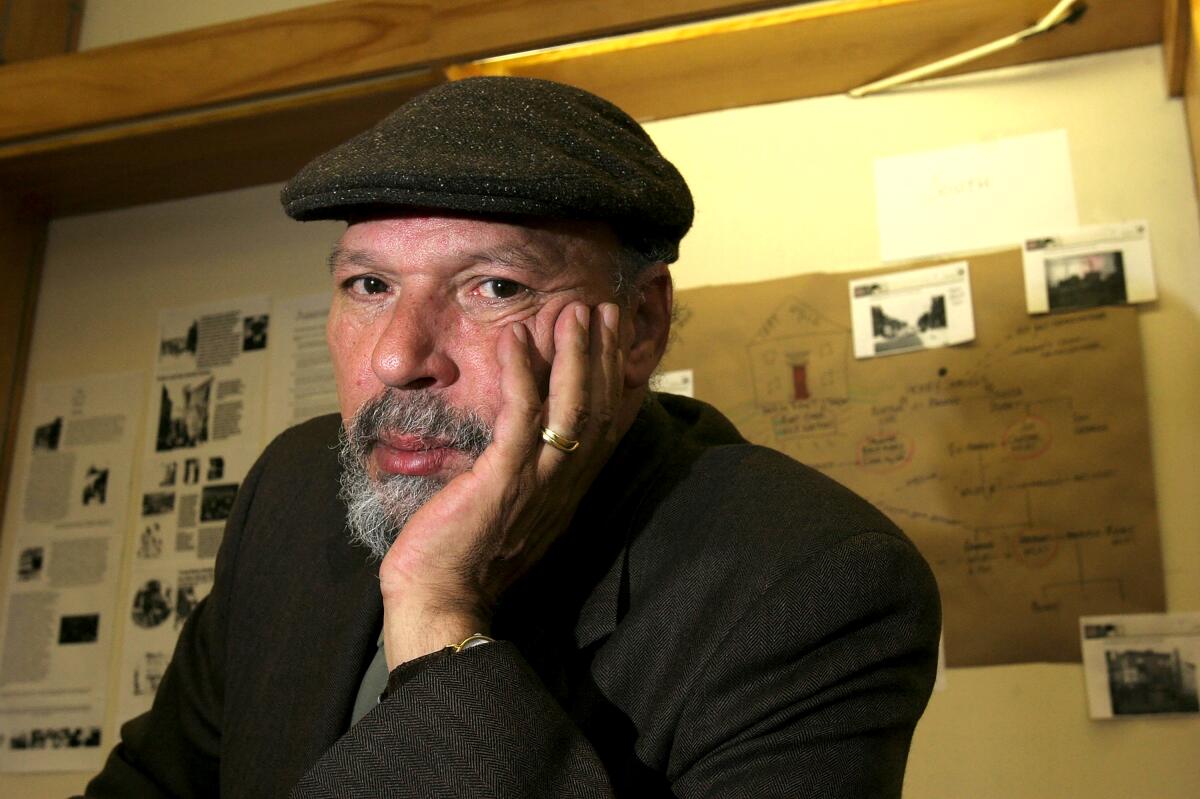

It wasn’t easy for Frederick August Kittel Jr., a high school dropout from Pittsburgh’s Hill District, to transform himself into August Wilson, the venerable playwright whose 10-play cycle examining 20th century Black life in America earned him a seat in the pantheon beside Eugene O’Neill, Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams and Edward Albee.

No dramatist survives the journey from obscurity to fame unscathed, but Wilson’s path was especially grueling. In addition to dealing with the usual economic pain and maddening fickleness of a system that enjoys bestowing favor only to take it away, he had to contend with the legacy of white supremacy, as deeply entrenched in the liberal bastion of the American theater as anywhere else in society.

Patti Hartigan’s “August Wilson: A Life,” an invaluable and highly absorbing new biography, traces Wilson’s groundbreaking trajectory from his penurious beginnings to his death at age 60 in 2005, which made the front pages of newspapers around the nation. Through high-profile revivals and star-studded screen adaptations, Wilson’s work lives on powerfully and prolifically. Hartigan’s book reminds us what it took for the man to become a monument.

August Wilson, the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright who sought to distill virtually the entire African American experience in a cycle of 10 earthy, poetic and spiritually questing dramas, died Sunday.

Raised by his mother, Daisy Wilson, he had only the most precarious relationship with Frederick August Kittel, the white Bohemian-born immigrant baker who was said to be his (and a few of his siblings’) biological father. Kittel, who was married, was an erratic and destabilizing presence in the household.

Wilson couldn’t understand how a man who neglected his children could be their real father. The scars of this wound established an early paradigm of Black maternal love and reckless white patriarchal cruelty that was serially reinforced as Wilson made his way in the world.

His reluctance to talk about his biracial background only seemed to provoke further questions. In a 1988 interview with Bill Moyers, Wilson was asked about his practice of writing almost exclusively about Black characters. Was he not denying part of his own heritage?

Accustomed to answering what would never be asked of a white author, Wilson patiently explained, “The cultural environment of my life, the forces that have shaped me, the nurturing, the learning, have all been Black ideas about the world.”

Skepticism about his identity wasn’t strictly a white phenomenon. Wilson was especially stung when Henry Louis Gates Jr. challenged his authenticity in the 1997 New Yorker article “The Chitlin Circuit.” “He neither looks nor sounds typically Black — had he the desire he could easily pass — and that makes him Black first and foremost by self-identification,” Gates wrote.

A central irony of Wilson’s life is that, despite the communal source of his artistry, he was fated to be an outsider. Misunderstood and racially tormented in Catholic school, he found refuge in inwardness.

Sister Mary Christopher recognized his writing ability and encouraged him to read his stories to the class. But not all his teachers had such a favorable view. The nuns would tell his mother, “He’s either going straight to the top or straight to the bottom. There is no middle ground for him.”

His formal education ended at Gladstone High School after a teacher accused him of plagiarizing a paper on Napoleon Bonaparte that he assiduously researched and wrote himself. Undeterred, he continued his studies at the Carnegie Library, where he read his way through the stacks. “I dropped out of school, but I did not drop out of life,” Wilson said of that turning point.

D.T. Max’s “Finale,” about Sondheim, and “Shy,” by Mary Rodgers and Jesse Green, bring the singular Broadway personalities back to life.

This resilience would carry him through decades of struggle. Wilson found his vocation as a street poet with a group of neighborhood bards known as the Centre Avenue Poets. But his voice as a writer took time to discover. He began composing verse in a flowery style, heavily influenced by Dylan Thomas and John Berryman. Amid the revolutionary currents of the 1960s, the young Wilson dressed like a literary gentleman from the 1940s.

The blues alchemized him. Listening to Bessie Smith was a sort of baptism: He submerged himself in what he called the “wellspring” of his art. “The universe stuttered and everything fell to a new place,” he recalled.

An equally powerful transfiguration occurred through his encounter with the work of the Black American artist Romare Bearden. “What I saw was Black life presented on its own terms, on a grand and epic scale, with all its richness and fullness, in a language that was vibrant and which, made attendant to everyday life, ennobled it, affirmed its value, exalted its presence.” These words, which appear in Wilson’s introduction to Myron Schwartzman’s 1990 biography of Bearden, serve as an eloquent summation of his own art.

The shift in Wilson’s poetry was dramatic — and led naturally to drama. “He started thinking, hard, about the banter he heard in Pat’s Place [a pool hall in the Hill District] and at the jitney station, about men sitting around signifying and telling lies,” Hartigan writes. Wilson recognized what was holding him back as a writer: “I didn’t value and respect the speech pattern ... I was always trying to mold it into some European sensibility of what the language should be.”

The road to becoming a playwright would have several false starts, including the musical “Black Bart and the Sacred Hills,” an epic disaster that might have derailed a lesser talent. He was a father in his mid-30s, living with his second wife in Minneapolis after filing for bankruptcy, when the future finally beckoned.

When August Wilson received word in 2005 that he had inoperable Stage IV cancer, he was not just personally but professionally disconsolate: There was still so much work to do.

After several rejected applications, Wilson was invited to join the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center’s National Playwrights Conference in 1982 to work on what would eventually flower into his breakthrough play, “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.” Lloyd Richards, the artistic director of the conference who directed the original Broadway production of “A Raisin in the Sun,” would guide Wilson’s playwriting evolution.

Hartigan’s biography is at its best in chronicling the artistic process that reshaped not only Wilson as a dramatist but also the producing structures of the American theater. As artistic director of the Yale Repertory Theatre and dean of the Yale School of Drama, Richards made available to Wilson a safe place to incubate and launch his works.

No sooner was Wilson admitted into the big leagues than the creative floodgates opened. In rapid succession he followed “Ma Rainey” with “Fences,” “Joe Turner’s Come and Gone” and “The Piano Lesson.” This period — one of the most breathtakingly fecund in the history of the American theater — was assisted by regional theater tours that gave him time to hone his plays before they hit Broadway.

Wilson’s artistic story, throbbing with the ancestral memory Wilson felt in his blood, is profoundly inspiring in Hartigan’s magnificent rendering. This unauthorized biography, forced to paraphrase many of Wilson’s letters, early plays and poetry, may not offer the kind of detailed critical readings found in other monumental biographies — James Knowlson on Samuel Beckett, Michael Meyer on Henrik Ibsen, Michael Holroyd on George Bernard Shaw. But the work is blessedly free of the endless plot summaries that weigh down Hermione Lee’s biography of Tom Stoppard.

“King: A Life,” by Jonathan Eig, chisels away the myth of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to reveal new layers and debunk falsehoods. Eig talks about how he got there

A former theater critic for the Boston Globe, Hartigan brings a sharp critical perspective to bear that keeps “August Wilson: A Life” from crossing over into hagiography. She loves her subject but remains clear-eyed about Wilson’s limitations, including the stereotypical leanings of his female characters and the muddled quality of some of his later plays. She identifies “Joe Turner’s Come and Gone” as the masterpiece of the cycle, recognizes “Fences,” “The Piano Lesson” and “Gem of the Ocean” as modern classics and responds to the irresistible vitality of speech rhythms in “Jitney” and “Two Trains Running.” All of this strikes me as unimpeachable.

There are other versions of Wilson’s life to be told — versions that give a more intimate look at his psychological complexity, versions that reckon more deeply with the roots of his Black imagination, versions of a more scholarly order — but Hartigan arrives at a satisfying balance.

It’s particularly moving to read this book in the wake of national reckoning that followed the murder of George Floyd. Wilson took enormous flak for calling out the systemic racism of the American theater. Robert Brustein even suggested Wilson was guilty of a “failure of gratitude” toward the system that had anointed him.

Straddling zeitgeists, Wilson was at once ahead of his time and the beneficiary of a particular moment in the history of American drama that may sadly be no more. As regional theaters across the country struggle to remain open in the face of dwindling audiences and rising costs, is the path of a 21st century August Wilson still possible?

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.