From the Archives: Playwright August Wilson Distilled Black America

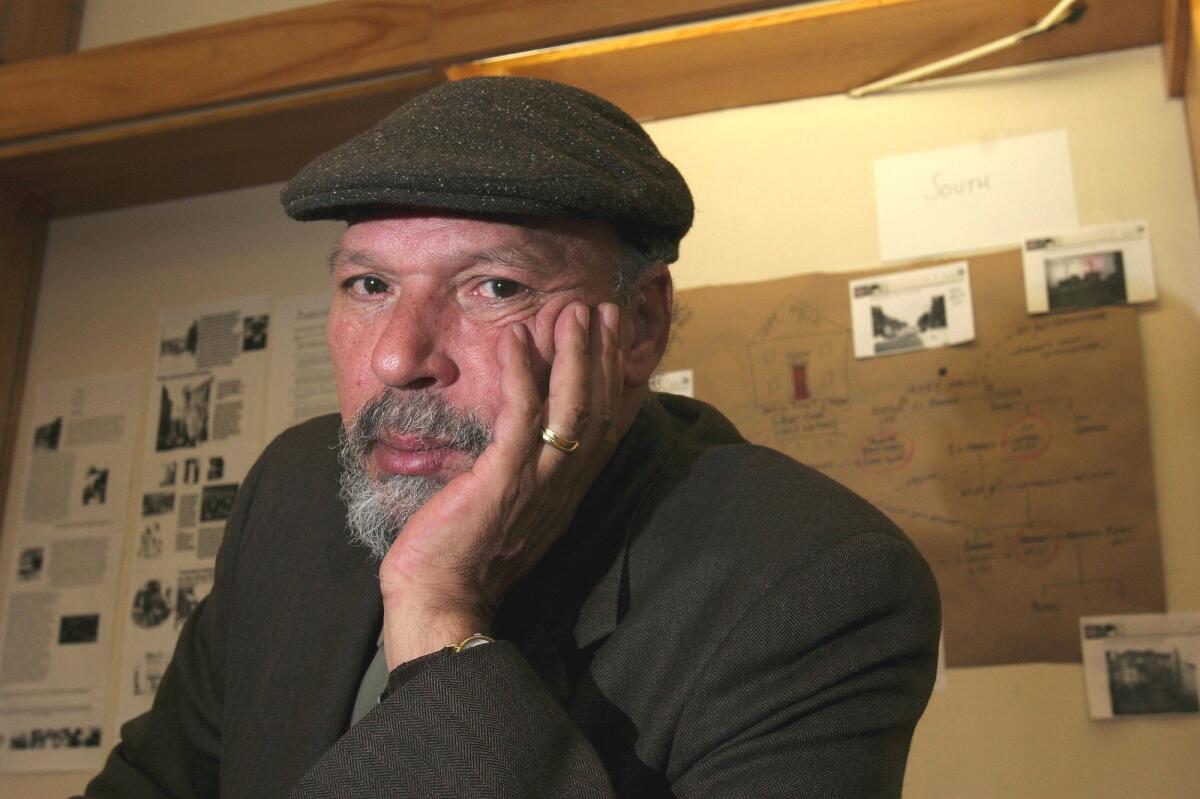

August Wilson.

- Share via

August Wilson, the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright who sought to distill virtually the entire African American experience in a cycle of 10 earthy, poetic and spiritually questing dramas, died Sunday. He was 60.

Wilson died at Swedish Medical Center in Seattle surrounded by his family, Dena Levitin, his personal assistant, said.

Doctors at the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle diagnosed Wilson’s liver cancer in June, but the disease was too advanced for treatment. Wilson announced in late August that he had only a few months to live.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

The obituary of playwright August Wilson in Monday’s A Section said Charles Fuller was the first African American playwright to receive the Pulitzer Prize for drama. Charles Gordone received the Pulitzer in 1970, 12 years before Fuller, for his play “No Place to Be Somebody.” The obituary also said Wilson had five siblings. He had six.

------------

“We’ve lost a great writer, I think the greatest writer that our generation has seen, and I’ve lost a dear, dear friend and collaborator,” Kenny Leon, who directed Wilson’s most recent play, “Radio Golf,” which just concluded a run in Los Angeles, told the Associated Press.

Leon, who also directed the Broadway production of Wilson’s “Gem of the Ocean,” said the playwright’s work “encompasses all the strength and power that theater has to offer.”

“I feel an incredible sense of responsibility on walking how he would want us to walk and delivering his work,” he said.

Tributes to the playwright began even before his death. On Sept. 1, Rocco Landesman, president of Jujamcyn Theaters, which owns five houses on New York City’s Broadway, announced that the Virginia Theater would be renamed this month the August Wilson Theater, the first on Broadway named after an African American.

Wilson grew up sharing a two-room apartment with his mother and five siblings in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, a poor black neighborhood that became the location for all but one play in his cycle, “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.”

A Play for Each Decade

From 1979, when he wrote his first version of “Jitney,” through rewrites after “Radio Golf” premiered last April, Wilson worked indefatigably on the cycle. The project — a play for each decade of the 20th century — did not become clear to him until the mid-1980s, when he realized that he had set each of several early plays in a different decade.

“I thought ... ‘Why don’t I just continue to do that?’ ” he told Howard University professor Sandra G. Shannon in 1991, in an interview later published in African American Review.

Wilson won acclaim in 1984 for “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom,” his first play to be prominently produced. Set in a 1920s Chicago recording studio, it explores the strife between blues singer Rainey and her band as they face exploitation by the white-run music industry.

With his career established after long years in which he supported himself with assorted jobs, including stock clerk, gardener, dishwasher and short-order cook, Wilson rapidly earned two Pulitzer Prizes — for “Fences” in 1987 (it also took the Tony Award for best play) and for “The Piano Lesson” in 1990.

His remarkably fertile period of the mid- to late 1980s also included his favorite, “Joe Turner’s Come and Gone” (1986), in which a man who had been hauled off for years of involuntary servitude in the Jim Crow South comes north in 1911, trying to find his long-lost wife. Wilson was also a Pulitzer finalist with all three of his plays that premiered during the 1990s: “Two Trains Running” (1990), “Seven Guitars” (1995) and “King Hedley II” (1999).

The cycle does not tell a continuous saga, but it is unified by setting, theme and style. Some characters pop up in two or more plays, either in person or in tales told by others — notably Aunt Ester, a kindly prophetess who is the central character of “Gem of the Ocean,” set in 1904. Most denizens of the Hill District take it on faith that she was born at the dawn of African slavery, and Wilson gives her the power to “wash” supplicants’ souls in racial memories that help them take sustenance from the past, rather than being overwhelmed by it. We learn of her death, at age 366, in “King Hedley II,” set in 1985.

Reviewing the concluding work of the cycle, “Radio Golf,” for the New Yorker in 2005, critic John Lahr marveled at the “unprecedented, magisterial” oeuvre created by this self-taught writer.

After premiering in April at the Yale Repertory Theatre — where six of Wilson’s plays were launched — “Radio Golf,” an account of black businessmen trying to pull off a redevelopment scheme in the Hill District in 1997, moved to the Mark Taper Forum for an August to mid-September run.

Gordon Davidson’s last production, capping 38 years as the Taper’s artistic director, was “Radio Golf.” He said the dying Wilson was able to muster enough strength and focus to do some rewriting even after the show opened at the Taper. The changes, including a honing of a central husband-wife relationship, were implemented for the last two weeks of the run, Davidson said.

With “Radio Golf,” L.A. is believed to be the first city in which the entire Wilson cycle has been staged, starting in 1987 with the Los Angeles Theatre Center’s production of “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.” In all, his plays have been produced more than 2,000 times in the United States.

Wilson dropped out of school at 15 after a series of racist indignities; the Hill District branch of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh became his do-it-yourself alternative school. He spoke proudly, years later, of the honorary high school diploma the library awarded him in 1999, when he returned to help celebrate the 100th anniversary of the branch.

As for his university, it was the black-awareness literary movement of the late 1960s. Wilson also crucially schooled himself just by paying close attention to the stories told by his Hill District neighbors and to their ways of telling them.

And his muse? Wilson invoked the blues as the driving wheel of his inspiration and as the source of his characters’ vibrant speech cadences and reflex-quick wit. Some of the plays include musical set pieces. For Wilson, the blues was a spirit, a way of being that infuses his characters with a survivalist ability to strive, or at least endure, even as the heavy legacy of slavery and racism circumscribes their lives.

“Blues is the bedrock of everything I do,” he told the Christian Science Monitor in 1991. “All these ideas and attitudes of the characters come out of it. Blues is the best literature that we as blacks have.”

He added his own chapter to theater literature. “Wilson’s output and quality ... have been extraordinary,” Lahr wrote as the 10-play cycle ended, noting that Eugene O’Neill was the only other American playwright even to have embarked on such an epic task — and O’Neill completed just two plays of a planned 11. (William Shakespeare wrote 10 historical plays spanning 400 years of medieval English royalty.)

“At least six of the plays in Wilson’s series ... are, I think, first rate, and one, ‘Joe Turner’s Come and Gone,’ is a masterpiece,” Lahr wrote.

In an introduction to “King Hedley II,” printed in “The Fire This Time,” a 2004 anthology of contemporary African American playwriting, Wilson said his mission had been to create a thorough and encompassing representation of African American culture.

“The manners and rituals ... the music, speech, rhythms, eating habits, religious beliefs, gestures, notions of common sense, attitudes toward sex, concepts of beauty and justice, and the responses to pleasure and pain ... have enabled us to survive the loss of our political will and the disruption of our history.... I wanted to place this culture on stage in all its richness and fullness and to demonstrate its ability to sustain us ... through profound moments of our history in which the larger society has thought less of us than we have thought of ourselves.”

Wilson’s project was not to dramatize political issues and historic events — Gertrude “Ma” Rainey is the only real-life figure in the cycle — but to show the weight of the present and the past as his characters go about their seemingly ordinary lives of struggle. There are only four whites in the entire cycle: a Chicago recording studio owner, a manager and a policeman in “Ma Rainey” and a peddler in “Joe Turner.”

“His plays,” Lahr wrote in a 2001 New Yorker profile of Wilson, “are not talking textbooks; they paint the big picture indirectly, from the little incidents of daily life.”

Although Wilson’s people are boxed in by economic want and blunted in their attempts at a decent material life, they can be buoyed by music, humor, tradition and the joy of conversation.

He ultimately leaves them either to drown amid their unforgiving material circumstances — often in violent climaxes — or to take hold of a sustaining spiritual awareness by embracing the African American past and finding strength there despite all its sacrifice and horror.

In “Joe Turner’s Come and Gone,” the voodoo-practicing street philosopher, Bynum, defines the individual’s — and the race’s — past as a “song” that can carry a person through life if it’s not forgotten. The past has become a prison for Loomis, the wandering, bereft, long falsely imprisoned man Bynum counsels in the following passage:

“When you look at a fellow ... you can see his song written on him. Tell you what kind of man he is in the world. Now, I can look at you, Mr. Loomis, and see you a man who done forgot his song.... A fellow forget that and he forget who he is. Forget how he’s supposed to mark down his life.

“Now, I used to travel all up and down this road and that.... Searching. Just like you, Mr. Loomis.... Then one day my daddy gave me a song. That song had a weight to it that was hard to handle.... I fought against it.... I tried to find my daddy to give him back the song. But I found out it wasn’t his song. It was my song. It had come from way deep inside me. I was making it up out of myself. And that song helped me on the road. Made it smooth to where my footsteps didn’t bite back at me.”

Wilson insisted fiercely — and controversially — that America needed a black theater that could stand on its own, inviting all audiences but under black control. The leading outlets for his own work were the white-dominated mainstream regional theaters and Broadway.

He also staked out what many thought was an extreme view that colorblind casting, the common practice of casting blacks (and other minorities) in classic theatrical roles originally written for whites, was a sham that would only weaken attempts to forge a strong black theater.

Most critics found a universal appeal in his plays, amid their single-minded specificity to black experience.

In “The Piano Lesson,” set in 1936, Wilson turned a common feature of Depression-era parlors, the upright piano, into an emblem of the black past and of the challenges blacks face in shaping their future. Berniece Charles regards the piano as a sacred relic to be left unplayed, its ornate carvings and bloody history a testament to horrors her family has endured. Her brother, Boy Willie, wants to sell it so he can buy a plot of prime Mississippi farmland their forebears worked as slaves.

Reviewing “The Piano Lesson,” Clive Barnes wrote in the New York Post that although the play takes place in “a microcosm largely remote, for many of us, from our own little worlds,” Wilson speaks “the language of humanity.... This is a wonderful play that lights up man. See it, wonder at it and recognize it.”

‘Rattles History’

Frank Rich of the New York Times was equally impressed, though less convinced that universalism was the note being sounded: “Like other Wilson plays, ‘The Piano Lesson’ seems to sing even when it is talking. But it isn’t all America that is singing. The central fact of black American life — the long shadow of slavery — transposes the voices of Mr. Wilson’s characters ... to a key that rattles history and shakes the audience on both sides of the racial divide.”

Wilson’s ability to turn black American experience into vivid drama — and to do it repeatedly for the stage while virtually ignoring the more lucrative tug of Hollywood — dovetailed with an emerging consensus among nonprofit regional theaters during the 1980s that they needed to better reflect the racially diverse communities they were chartered to serve. If Wilson hadn’t existed, diversity-minded theaters may have had to invent him.

Unlike Lorraine Hansberry, author of “A Raisin in the Sun,” who died of cancer at age 34, and Charles Fuller, whose “A Soldier’s Play” in 1982 became the first by an African American to receive the Pulitzer Prize for drama, Wilson delivered steadily for more than 20 years.

And at a time when serious plays were considered almost an endangered species on Broadway, Wilson’s -- despite their tendency toward audience-taxing three-hour lengths — regularly made it onto New York’s stages.

Davidson, who worked with Wilson as an L.A. producer from the late 1980s onward as his plays arrived at the Taper and its sister theater, the Ahmanson Theatre (or, for a time, the Doolittle Theater), said that although Wilson’s cycle of plays did supply a growing need for theaters bent on multicultural programming, the shows earned a place on their merits.

“I don’t think it had anything to do with affirmative action,” Davidson said. “His importance is that he has a voice, and that voice was worth hearing. He’s a great storyteller, he’s a poet and there’s music in his writing, and there is a willingness [on the part of regional theaters and their predominantly white subscription audiences] to be part of that experience.”

One of those neither shaken nor stirred by Wilson’s plays was drama critic Robert Brustein, the founding director of both the Yale Repertory Theatre and Harvard’s American Repertory Theatre. “This single-minded documentation of American racism is a worthy if familiar social agenda,” Brustein wrote of Wilson’s oeuvre as he assessed “The Piano Lesson” for the New Republic in 1990. “No enlightened person would deny its premise, but as an ongoing program it is monotonous, limited, locked in a perception of victimization.”

By 1997, Brustein and Wilson were debating their differences in front of an audience at New York City’s Town Hall, focusing on Wilson’s call for a black theater independent of the existing theater establishment. He had first delivered that call in “The Ground on Which I Stand,” a 1996 keynote address to a conference of the Theatre Communications Group, a service organization for nonprofit theaters.

Wilson tried to turn his ideas into action by convening two national black theatre summits in 1998, at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H., and in Atlanta. Out of them grew the African Grove Institute for the Arts, a nonprofit group devoted to cultivating black performing arts organizations across the country; Wilson was founding chairman.

Childhood Memory of Racism

A native of Pittsburgh, Wilson grew up as Frederick August Kittel, the firstborn son and namesake of his white father. The elder Kittel was a hard-drinking German immigrant who worked as a baker and was seldom with his family. Wilson’s mother supported the family by cleaning houses and sometimes relied on welfare payments.

One of Wilson’s favorite childhood memories concerned the time a radio station ran a contest, and his mother phoned in with the correct answer. The prize was supposed to be a new washing machine, but the station tried to give her a secondhand one when it found out that she was black.

She refused, saying, “Something is not always better than nothing,” Wilson told the Boston Globe in 2005.

Wilson had reached his teens when his mother, divorced from Kittel, married David Bedford, a sewer worker and former star high school athlete who had served 23 years in prison. The New York Times reported in 1987 that Bedford had killed a man while holding up a store to get money so he could go to college.

There were elements of Wilson’s stepfather, who died in 1969, in Troy Maxson, the great but bitter former baseball player turned trash collector in “Fences.” James Earl Jones won the 1987 Tony Award for best actor playing the part.

During his ball-playing days, Maxson had been on the wrong side of the major leagues’ racial barrier, which didn’t fall until the arrival of Jackie Robinson in 1947. The play is set in 1957, and Maxson perversely blocks his talented son’s athletic ambitions, claiming that racists will only thwart him if he tries.

After Wilson’s mother married Bedford, his family moved to a mostly white neighborhood of Pittsburgh; there, Wilson recalled, racist notes were left on his desk at school. He transferred but dropped out when, as he described it to a British newspaper, the Guardian, an African American teacher accused him of plagiarizing an essay on Napoleon.

“I said, ‘If I hadn’t written it, I wouldn’t have put my name on it.’ I tore it up, threw it in the wastepaper basket and walked out of school,” never to return.

The public library became his haunt, especially the “Negro” section, where he discovered Ralph Ellison, Langston Hughes and James Baldwin. Later, the writings of Malcolm X spoke to him about the need for black cultural self-sufficiency.

“Those books were a comfort,” he told the Guardian. “Just the idea that black people could write books. I wanted my book up there too.”

By his late teens, after a year in the Army, Wilson had bought his first typewriter, immersed himself in the blues and jazz and was beginning to write poems and stories.

He transformed himself from Freddie Kittel to August Wilson, taking his mother’s birth name after his father’s death in 1965. He joined a Pittsburgh poets’ collective, then became co-founder of a grass-roots theater company, Black Horizons on the Hill.

Some of his poems were published in black periodicals and anthologies. Although Wilson later spoke of publishing a book of poems, as well as a novel, he never did.

His first full-length play, “Recycle” (1973), produced at a community theater in Pittsburgh, concerned his failed three-year marriage to Brenda Burton, a member of the Nation of Islam. They had a daughter, Sakina. Wilson was married twice more: to social worker Judy Oliver from 1982 to 1990, and in 1994 to Constanza Romero, a costume designer with whom he had a daughter, Azula. His wife survives him, as do his two daughters.

As he began to write for the stage, Wilson absorbed the late 1960s plays of black dramatists Ed Bullins and LeRoi Jones (later known as Amiri Baraka). But he recalled a 1976 production in Pittsburgh of the white South African playwright Athol Fugard’s “Sizwe Bansi is Dead” as the moment when “the theater came alive for me.”

A Pittsburgh theater friend, Claude Purdy, had moved to Minneapolis and invited Wilson to visit. Wilson settled there in 1978 and began working with the Penumbra Theatre, an African American company.

After settling for odd jobs through his teens, 20s and early 30s, Wilson began earning a living as a writer for the first time, creating scripts for plays that accompanied exhibits at the Science Museum of Minnesota. He lived in Minneapolis for 12 years until his divorce from Oliver, then moved to Seattle.

Wilson told Shannon, the Howard University professor, that the move was a way of coping with his second divorce; he had visited the city and liked it, and “it was as far away from New York as I could get.”

By 1980, Wilson had begun sending unsolicited scripts to the National Playwrights Conference, a prominent annual play-development program at the Eugene O’Neill Theater Center in Waterford, Conn. Among the rejects was “Jitney,” a play about unlicensed cab drivers, which had been produced in Pittsburgh in 1979 and was revised and taken on a four-year tour starting in 1996.

In 1982, Lloyd Richards, the O’Neill Center’s artistic director and dean of the Yale School of Drama — he was Brustein’s successor at Yale — read the draft of “Ma Rainey” that Wilson had submitted and invited him to develop it at that year’s playwrights’ conference.

For the next 14 years, encompassing six plays of the cycle, Wilson and Richards, were a writer-director team. Together, they began Wilson’s career-long practice of honing works through several productions in regional theaters, often making substantial changes before bringing them to Broadway.

Lahr’s New Yorker profile noted that through the gradual process of watching, rethinking and rewriting, Wilson trimmed more than 90 minutes from the first 4 1/2 -hour version of “Fences;” the eventual ending to “The Piano Lesson” didn’t dawn on him until the show had been on tour for a year, after Richards suggested bringing in a ghostly presence.

“He hears the language of his people,” Richards told the Los Angeles Times in 1996.

‘My Mentor, My Provocateur’

In a 1987 interview with the New York Times, Wilson described Richards as “a kind of surrogate parent.” The playwright’s introduction to “Three Plays,” an early collection, described Richards as “my guide, my mentor, my provocateur.... His hand has been firmly on the tiller as we charted the waters from draft to draft and brought the plays safely to shore without compromise.”

Still, even critics who respected and admired Wilson’s plays could find gaps and flaws. Too talky, too long, too skimpily plotted, too many hard-to-swallow leaps into the metaphysical and the supernatural, not enough fully drawn female characters.

“When ghosts begin resolving realistic plays, you can be sure the playwright has failed to master his material,” Brustein sniffed, regarding “The Piano Lesson.”

To Charles McNulty, Los Angeles Times theater critic, what sets Wilson apart and seals his legacy is not so much how he told his stories — McNulty said he broke no new ground in dramatic structure and technique — but the fact that those stories had rarely been seen on mainstream stages and were told in spot-on dialogue and memorably drawn characters.

“There’s something slightly old-fashioned about Wilson’s storytelling; his plots can feel labored,” McNulty said, especially when compared to the innovations achieved by contemporaries Sam Shepard and David Mamet.

“Yet the range of African American voices he captured, the historical and psychological complexity with which he explored the ongoing legacy of slavery, the salutary effect of his political anger and the multitude of memorable roles he gave to black actors ensure his place at the top of modern American drama,” he said.

Wilson wrote his initial drafts in longhand; he liked to work at night and enjoyed hanging out in down-to-earth eateries and coffee shops, observing, soaking up the conversations around him and crafting scenes.

Ultimately, Wilson told the Los Angeles Times in 1996, all his characters were manifestations of himself. “Some are from deeper inside than others, but they’re all different aspects of my personality, I suspect. They’re not modeled after anyone that I know. They are voices of the black community.”

An intense, thoughtful and sometimes publicly combative personality, Wilson also had his own style of bearing, sporting a Vandyke beard and cap. He gave voluminous interviews as he churned out his plays and took them on tour, year after year. But he wasn’t necessarily at home in the spotlight.

“There is an aura of tension and discomfort about him, as though he would rather be listening -- more specifically, overhearing -- than talking,” the Washington Post observed in 1991. “He is a chain-smoking, stern, imposing, complicated kind of guy.”

Wilson never did hit it off with Hollywood. A proposed film of “Fences” got sidetracked when the playwright insisted that it needed an African American director, not the studio’s pick, Barry Levinson, to capture the right tone. The only screen version made from one of his plays was a television film of “The Piano Lesson.” With a teleplay by Wilson that earned a 1995 Emmy nomination, and with Richards directing, it starred Charles S. Dutton and Alfre Woodard.

Although Wilson’s plays helped launch some future film stars — including Laurence Fishburne and Samuel L. Jackson — he said his interests simply didn’t coincide with the kinds of movies the film industry wanted to make.

“The offers I’ve had from Hollywood are for the most part to write biographies, as though that’s the only kind of black material they are willing to look at,” he told the Washington Post. “I want to write an original play or film script, with ideas.”

Wilson regularly told interviewers that from 1980 to 1991, he went to just two movies: “Raging Bull” and “Cape Fear,” according to Lahr, both directed by Martin Scorsese and starring Robert De Niro.

He liked to describe himself as “a struggling playwright,” because he always was grappling with language, trying to put yet another drama on paper. In those perpetual struggles, he found his contentment.

Wilson told the Guardian that, after finishing “Gem of the Ocean,” the penultimate play in the cycle, “I immediately got depressed. It’s like you temporarily lost your reason for living, and the only thing to do is start another. So I will write down a title or a line of dialogue or an idea for a character or something. So, if someone asks me what I am doing, I can say, ‘I’m working on my new play.’ ”

With the cycle done and “Radio Golf” into its opening run, Wilson told interviewers last spring that he was already cooking up the first play of his next phase: a comedy, he told the New York Times, that would involve “a war between coffin makers and undertakers, Death taking a holiday, Queen Victoria and the Platters, Benny Goodman and a magic radio.”

In 2003, he jumped into acting, premiering “How I Learned What I Learned,” a solo show about his early life, at the Seattle Repertory Theater.

“For me, there’s nothing in life that can compare to those moments of sitting there with that blank page, then to have something emerge out of it,” he told the Chicago Tribune in 2000. “You keep pressing, wrestling with it, then — bingo! — it starts to emerge. Then you’re really excited. You think, ‘This might be something after all.’ ”

Ex-Chief Justice Rose Bird Dies of Cancer at 63

Jazz Great Duke Ellington Dies in New York Hospital at 75

Consummate Entertainer Sammy Davis Jr. Dies at 64

Prominent Angeleno A.C. Bilicke Among the Dead

Nat ‘King’ Cole Dies of Cancer

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.