Salman Rushdie’s new novel reminds us how his writing changed the world

- Share via

On the Shelf

Victory City

By Salman Rushdie

Random House: 352 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

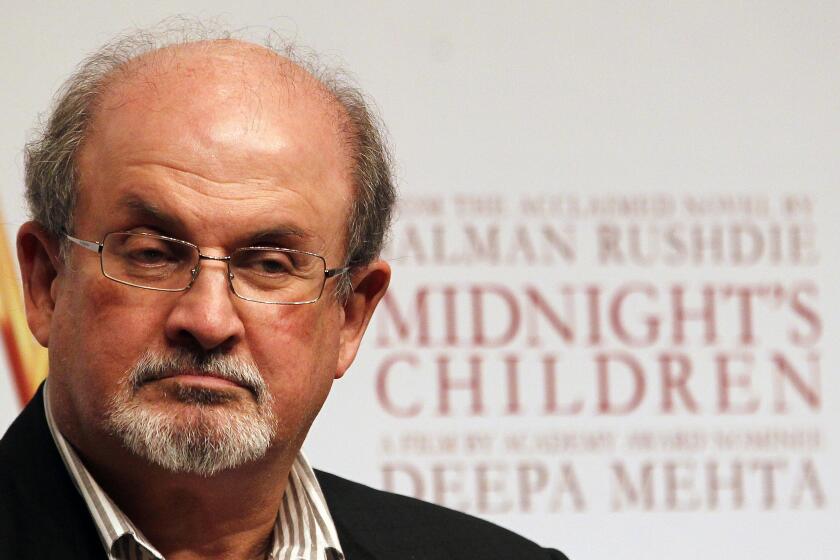

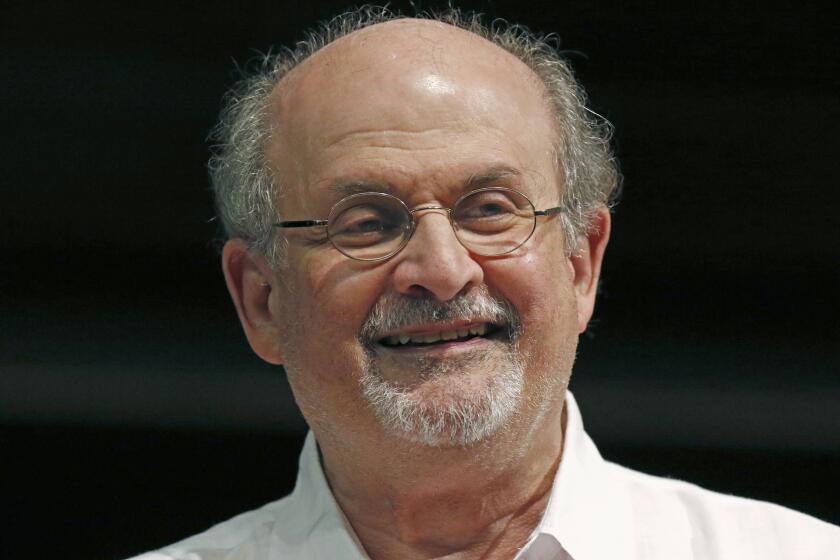

It is impossible to talk about Salman Rushdie’s work without acknowledging that he is that Salman Rushdie. The Rushdie who went into hiding because of the 1989 fatwa over his book “The Satanic Verses,” eventually reentered public life, big-time, and was brutally attacked onstage last August. Rushdie is a novelist whose writing is prolific, exuberant, extravagant, magical, expansive, mythological, brilliant — and he is also the man who has lived under decades of threats that are all too real.

As he releases a new novel, “Victory City,” Rushdie has returned to seclusion, declining media requests. He has not made a public appearance since the attack that left him gravely injured. Rushdie’s absence speaks volumes. How can we tell the dancer from the dance? The writing and the writer are one.

“The public attack on Rushdie’s life, while publicly exercising his right to free speech, will surely affect how his work is received and, broadly, how we perceive the role of writers as public intellectuals,” said Ana Cristina Mendes, a professor at the University of Lisbon and author of the book “Salman Rushdie in the Cultural Marketplace.” Rushdie is, especially now, a kind of secular saint who was nearly sacrificed for free speech.

When the author was rushed to the hospital after being attacked by a knife-wielding assailant in 2022, “Victory City” had already been announced. Out next week, it is a sweeping Rushdie-fied history of the Vijayanagara Empire, which ruled southern India from the 14th to the 16th century, told by Pampa Kampana, the 247-year old woman who created it all.

The book spans Kampana’s extra-long life, which kicks off when, as a child, she watches her mother and the other women in her village commit mass suicide. She imagines that women might not be subordinate to men, goes mute for nine years and is touched by a god. After that, she helps bring the city into being — the land and circumstances and people — then whispers dreams and histories to these new citizens so they can live and grow. Witnessing generation after generation, she’s our narrator once removed; the prose narrative is recorded by an unseen translator, who occasionally shares Kampana’s “original” verse and sometimes argues with an imagined critic/editor.

Rushdie was taken by helicopter to a hospital. “The news is not good,” his agent said, adding that he had nerve and liver damage.

Like a typical human, she has marriages and love affairs, births children, attends festivals and shops for mangoes. Yet like very few of us, she learns sword fighting, makes an enemy of a powerful religious leader, marries one brother after another, turns at will into a bird. There are battles and alliances and wars won and lost. How much of this derives from the myths and true history of the Vijayanagara Empire I can’t say, as my first encounter with it was in Rushdie’s end notes about his research.

Following two novels by Rushdie in a more comic vein set in some of the more absurd precincts of the modern U.S., “Victory City” feels like a return to form, recalling the kind of reality-bending, effortlessly erudite world-building that first defined his style — and may be key to his literary legacy.

“This is very typical of his work,” Mendes explained. “The style of his literary texts is characteristically hybrid or syncretic, drawing on Indian and Western literary tropes and weaving Indian literary traditions into the English language in ways that come across as verbal pyrotechnics.

“From my experience,” she continued, “we can only enter Rushdie’s narrative universe if we accept our historical and cultural ignorance of the many-layered contexts he sets his novels. To know all the references he deploys in his texts would be an extremely time-consuming and, perhaps, self-defeating endeavor.”

This gives some comfort to a reader who, say, might be unfamiliar with this history of South Asia, allowing her to take pleasure in recognizing a line from James Joyce while realizing there’s much passing her by (an experience not unlike reading Joyce himself).

But it’s not the only way to enjoy reading Rushdie. Alan Johnson, a professor at Idaho State University who teaches Rushdie to his undergraduates, points to the breadth of Rushdie’s references as part of what makes his writing special. “Midnight’s Children,” published in 1981, is Rushdie’s greatest work, Johnson says, because it is “a kaleidoscopic, idiosyncratic, virtuosic book of magic realism (and comic realism) that interweaves an astonishing number of themes, images, characters, cultural motifs and histories.”

The author recalls the landmark book with joy -- and some pain.

“As someone who was born and raised in India,” Johnson added, “I can say that Rushdie manages to capture voices, places and events both accurately and vibrantly, bringing them to life. I relish, for example, the Hindi-English puns, the intersecting Hindu-Muslim-Christian cultures of Bombay (not to mention Goa) and the ever-present, ever-playful wit.” Johnson noted global literary references including works by Cervantes, Laurence Sterne, Gabriel García Márquez and Günter Grass intersecting with Hindu epics and folktales.

Rushdie was born in pre-Partition India and schooled in England before making his home in England and the U.S.; he is a product of both colonialism and its dissolution. “Midnight’s Children” was a breakthrough sensation, winning the Booker Prize. It landed just three years after Edward Said’s critique of the western gaze, “Orientalism,” which helped lead a dramatic shift within the academy and broader literary circles to decenter European and American voices. “Midnight’s Children” was soon understood to be a landmark work. “Rushdie has been a representative voice of postcolonial literature since then, whether he intended it or not,” Mendes said.

And yet the cultural shift has continued dramatically in the decades since. Rushdie “has managed and succeeded over the decades to subvert expectations of orientalization by publishers, critics and readers, often through strategic, consciously articulated self-orientalization,” Mendes said. If that sounds like a contradiction, it points to how Rushdie consciously plays with the complexities of being who he is.

Way back in 1982, Rushdie published a widely referenced essay, “The Empire Writes Back With a Vengeance,” which remains essential to what Mendes describes as the “expectations that postcolonial writers write back to the metropolitan center.” In the years since, Rushdie himself has been seen as less a postcolonial messenger than a transnational literary celebrity.

That celebrity was, at times, thought to be unearned. Some commentators, Mendes noted, “had it that Rushdie’s investment in public performance was intended to court controversy after the fatwa; that he capitalized on his experience of being forced into hiding (at the expense of British government funds); that he fed a public perception of a controversial figure to boost book sales.” The August attack on him — 33 years after the fatwa issued by Ayatollah Khomeini — proved that every precaution taken was necessary.

Patt Morrison talks with Salman Rushdie, the British Indian novelist and essayist.

Close to the end of “Victory City,” the narrator is blinded by an angry rival. Rushdie lost an eye in the attack at the Chautauqua Institution. But according to Random House, his publisher, the manuscript was already completed. The passages are terrifyingly prescient, imagining how a blinded writer might feel.

Kampana is asked, “Is there still something you hope for, something you want? I know, your lost eyesight, of course. … But some secret desire?”

“My time of desiring is over,” Kampana replies. “Now everything I want is in my words, and the words are all I need.”

It’s true for every writer, in the long run; the words will have to be enough.

Kellogg is a former books editor of The Times. She can be found on Twitter @paperhaus.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.