Review: Salman Rushdie’s new novel ‘Two Years’ lets the jinn out of the bottle

- Share via

In his new novel, Salman Rushdie lets the genie out of the bottle and puts her straight into the arms of a 12th-century philosopher. Their relationship kicks off a story that pits reason against religion, imagination against order, and genies against puny humans.

Rushdie corrects “genie” to “jinn,” the original Arabic for the fantastical creatures born of fire with the ability to shape-shift. Featuring in Islamic mythology and pre-Islamic folk tales, the jinn’s characteristics are as varied as the many cultures that recognize their intercessions in human affairs. Rushdie builds his own cosmology around them:

“The jinn are not noted for their family lives. (But they do have sex. They have it all the time.) There are jinn mothers or fathers, but the generations of the jinn are so long that the ties between the generations often erode.... Love is rare in the jinn world. (But sex is incessant). The jinn, we believe, are capable of the lower emotions — anger, resentment, vindictiveness, possessiveness, lust (especially lust) — and even, perhaps, some forms of affection....”

These creatures lay siege to humanity in “Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights” for exactly that long — and the time tallies up to 1,001, a reference to “The Arabian Nights” and Scheherazade’s many stories. Set predominantly in the present day with a few flashbacks, the story is framed by anonymous chroniclers a thousand years hence recalling the events that transpired, giving them the glow of legend.

We begin in the 12th century when Dunia, a jiniri (female jinn) takes the form of a 16-year-old girl who, fascinated by his humanist take on reason and religion, falls for the elderly philosopher Ibn Rushd. The similarity between Rushd and Rushdie is not incidental — the author’s father took the family surname from the philosopher, known as a progenitor of Islamic secularism (in the West, he’s often called Averroës).

The fictional version of Rushd fathers a huge brood with Dunia. Sometimes, exhausted by his youthful lover’s ardor, he explains his ideas to her, philosophy as pillow talk. What is still controversial in some circles today was, in his time, also dangerous.

“[Rushd] was a sort of anti-Scheherazade, Dunia told him, the exact opposite of the storyteller... her stories saved her life, while his put his life in danger.” This is just one of the book’s many self-aware references — to both Rushdie’s real-life past and Scheherazade’s tales, which the novel mirrors with its stories-within-stories.

Some are grounded and physical, like the tale of Geronimo Manezes, a New York gardener past his prime who misses the country he left, India, as much as the wife he lost. Others are all about language: Blue Yasmeen, a spoken-word artist, remembers her dead father and spins on-stage stories with style and passion. Still others — like the centuries-old debate between Rushd and his deeply religious opponent, Ghazali — are making arguments about God and reason, imagination and science.

Geronimo comes into the possession of a magic storytelling box that serves as a mirror for the book’s structure. “[A]s each layer fell away a new voice told a new tale, none of the tales finished because the box inevitably found a new story inside each unfinished one, until it seemed that digression was the true principle of the universe, that the only real subject was the way the subject kept changing.”

The shift from one story to the next is lightning-fast, only occasionally signaled by something as formal as a chapter change or italics. The narrative is a speeding cacophony, each person’s life story or heartbreak or moment in time deftly rendered then abandoned in a long fleet-footed riff.

This is Rushdie’s first book for adults since 2008, and he seems to be having fun with the adult content. He works in jokes about the sexual appetites of his jinn, brings alive dark corners of Manhattan, explores misplaced love, and creates a good-versus-evil battle that’s firmly grounded in philosophy.

He has packed the novel with allusions, and while I can catch the veiled references to Nikolai Gogol’s story “The Overcoat” and Luis Buñuel’s film “Un Chien Andalou” and know without being told that George Simenon was an absurdly prolific French noir writer, that only makes me realize how much else there is — particularly in terms of religion — to discover.

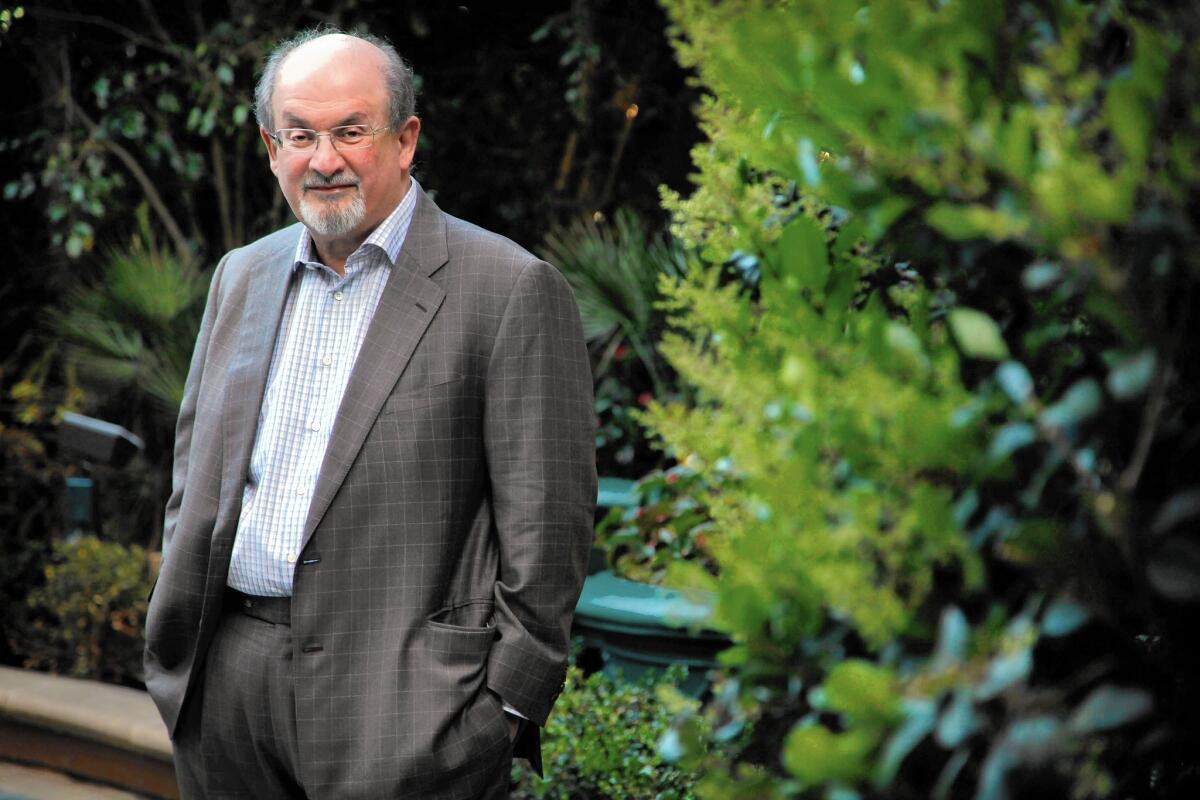

The writing isn’t slowed by the plethora of references, which speed by faster than most will be able to catch. Rushdie, 68, may be the only person with the multicultural experiences to be able to understand them all. Born in Bombay (as it was then known), educated in England, world famous after the Ayatollah Khomeini declared a fatwa against him for his 1988 novel “The Satanic Verses” and now a New Yorker, Rushdie is a unique polymath.

“Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights” is erudite without flaunting it, an amusement park of a pulpy disaster novel that resists flying out of control by being grounded by religion, history, culture and love.

::

Two Years Eight Months and Twenty-Eight Nights

Salman Rushdie

Random House: 304 pp., $28

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.