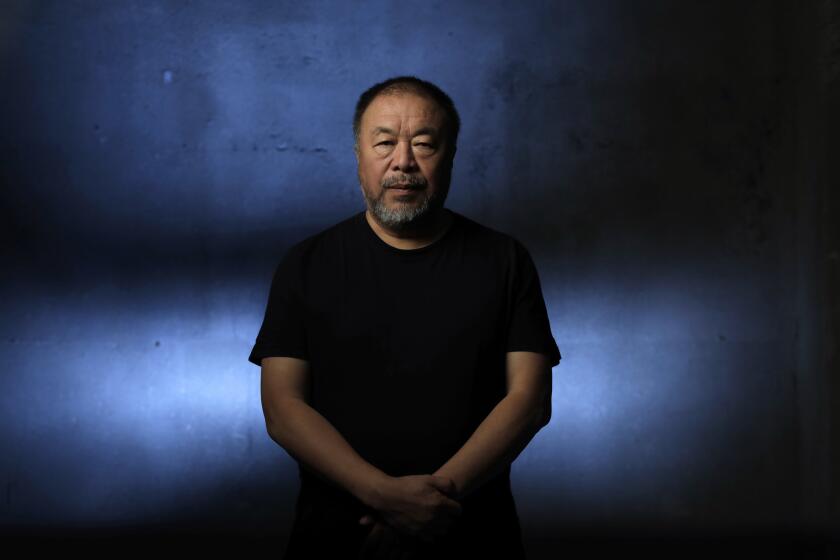

Chinese artist Ai Weiwei on his memoir, his persecution and ‘why autocracy fears art’

- Share via

On the Shelf

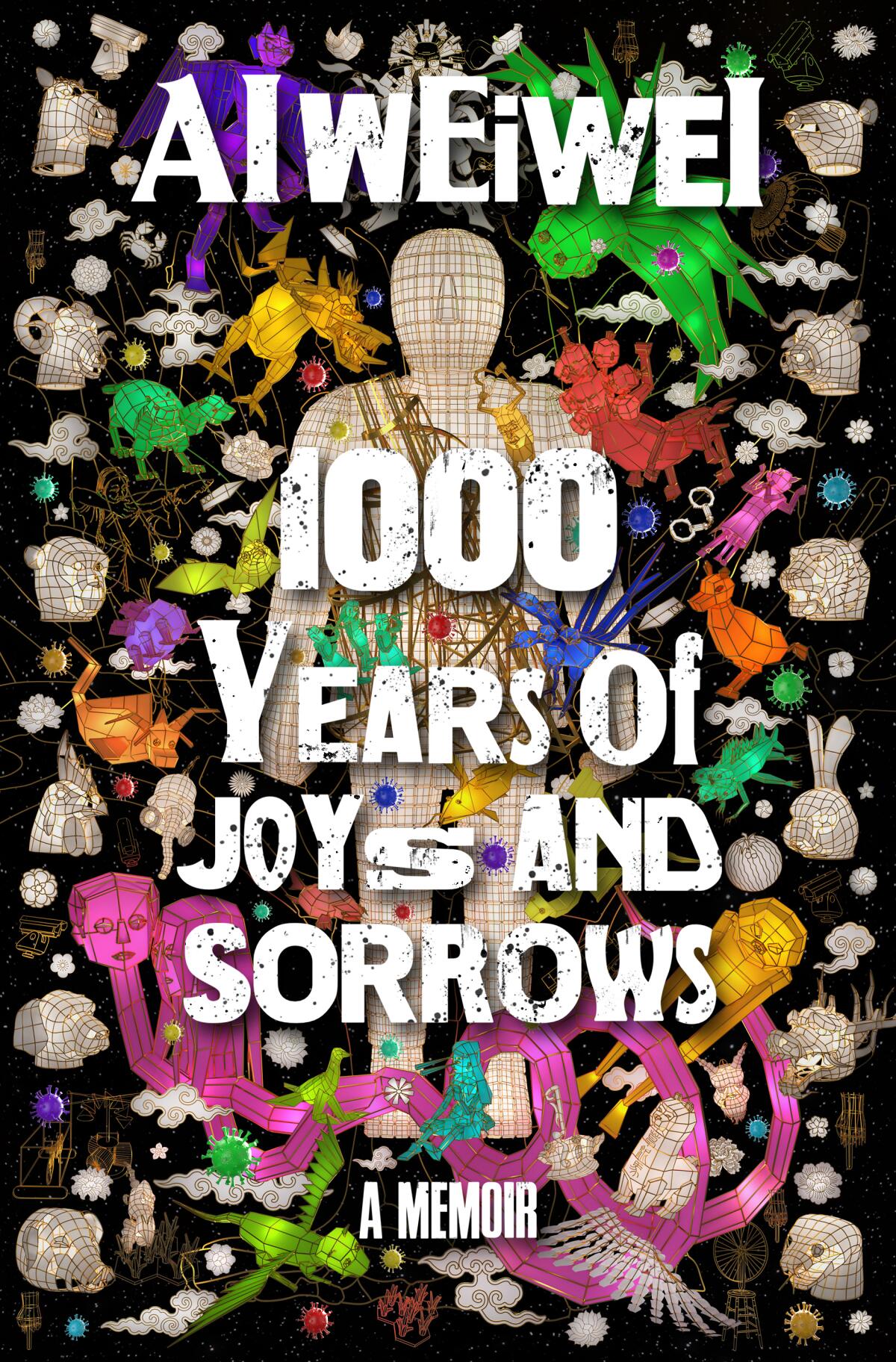

1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows

By Ai Weiwei, trans. by Allan H. Barr

Crown: 400 pages, $32

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

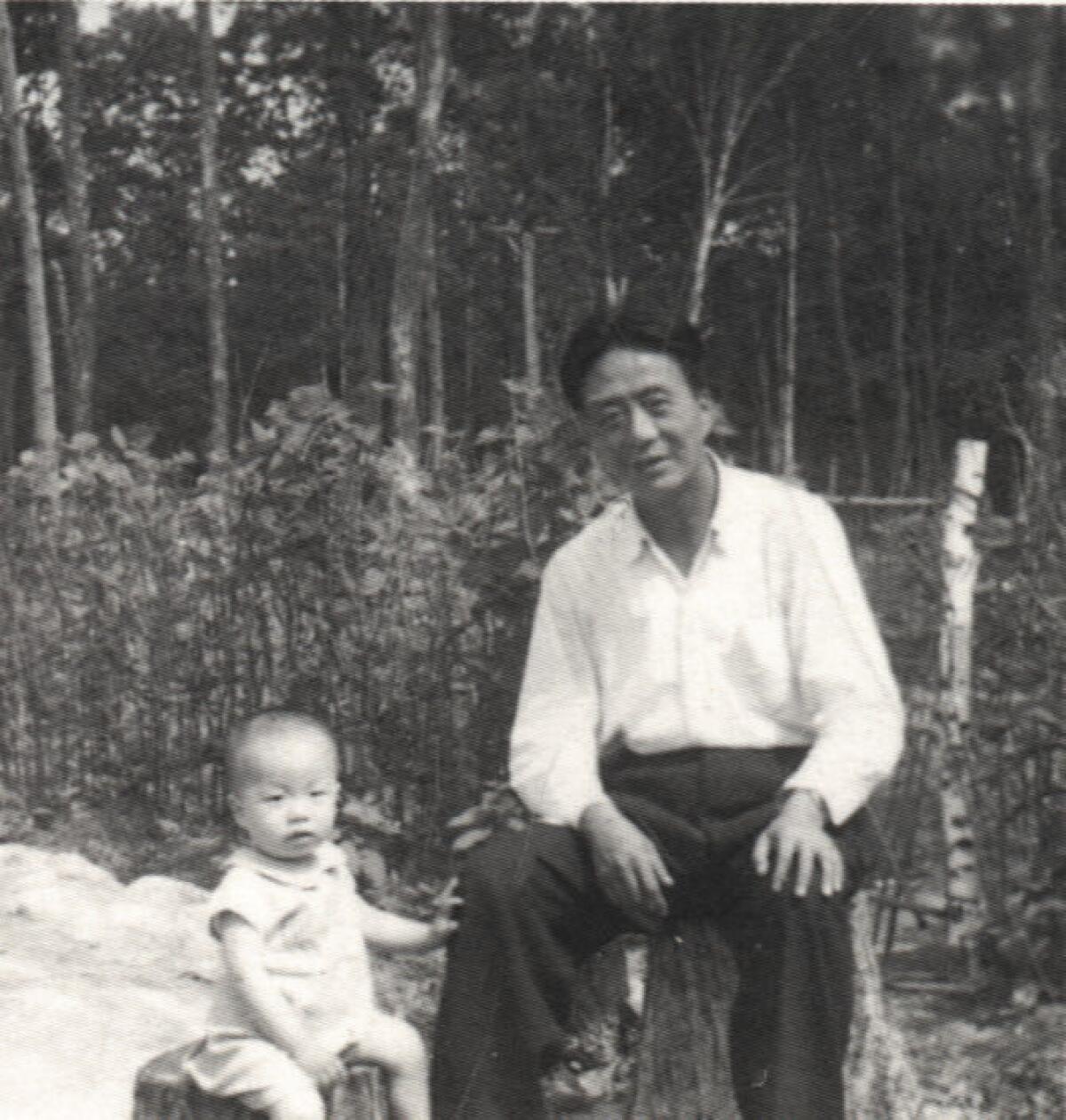

Two people activate artist Ai Weiwei’s new memoir, “1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows”: his father, renowned poet Ai Qing, and his 12-year-old son, Ai Lao. As a child, Ai watched his father suffer the humiliations and privations of political persecution. As an adult he became China’s preeminent contemporary artist and, almost inevitably, another government target.

“During those long weeks in secret detention my fear was not that I might not be able to see my son, but that I might not have the chance to let him really know me,” Ai writes of his 81 days in Chinese custody in 2011. “So the idea came to me that if I was released, to bridge the gap between us,” he would write a book, partly to explain to his son “what life means to me, why freedom is so precious, and why autocracy fears art.”

Though Ai is best known for his collaboration on the Beijing National Stadium, a.k.a. the Bird’s Nest, his larger body of work is inseparable from his human rights advocacy in China and beyond. That makes his memoir, like his career, an alchemical mix of art and activism.

“After going through this kind of struggle, you cannot be a pure art-for-art’s sake artist,” he says during a recent phone call from his home outside Lisbon. “Everything accumulates gradually, so many injustices I have seen for my family, and other families, so much difficulty during Chairman Mao’s time and so much political struggle. And it stayed with me.”

The Ai family’s persecution began the year Ai Weiwei was born, 1957. During a political purge, Ai Qing was condemned for defending fellow modernist author Ding Ling and sent to live in the country’s far northeast. Two years later he was sent west to Shihezi in Xinjiang, currently home to China’s embattled Uyghur population.

“My father was the No. 1 enemy and had to clean everybody’s s—hole,” Ai recalls. “He was forbidden to write. He could not do what he loves the most, but he was insulted and humiliated with daily confrontations with people, most of them not well educated. It’s a horrible struggle when you don’t have daily nutrition, you have nothing. It’s the bottom of surviving.”

Ai Qing was rehabilitated in 1961 with a good word from then-Vice Premier Xi Zhongxun, the father of current President Xi Jinping. Even so, as the Cultural Revolution raged on into the 1970s, Ai Qing decided his expansive book collection might put the family in jeopardy.

“When I see he has to burn those books he loved and we all loved, all those images ... all the poetry ... you feel something is dead,” Ai recalls. But he also recognizes the power implied in the need to destroy them. “Those writings and those images are a real threat to someone or some system.”

In 1976, the Ais returned to the capital. Weiwei studied animation at the Beijing Film Academy and co-founded the Stars, an early avant-garde art group. In 1981 he went abroad to study in the U.S. and wound up staying in New York until 1993. On East 7th Street he lived just a few blocks from an old acquaintance of his father, Allen Ginsberg.

“He reminded me of my father,” Ai says of the Beat poet. “They created this inner world which has a clear texture and light and you can walk into it. It’s a world I’m familiar with because of my father.”

Ai’s influences in New York included Jasper Johns and Marcel Duchamp, a profile of whom Ai fashioned out of a wire coat hanger. “Duchamp saved my artistic life,” he says. “For me, he’s a Zen master and he doesn’t know it.”

In 1993, Ai returned to China after a dozen years abroad; it was not a warm homecoming. “I don’t like Beijing, I don’t have good memories,” Ai says now. “I became another person from the past — not a person from New York, but I didn’t belong to Beijing.”

Ai Weiwei discusses his new film, “Yours Truly,” probing his life and work -- and meeting the current moment with art

Even so, 15 years later the city was the site of his most famous artistic achievement, the Bird’s Nest, centerpiece of the 2008 Olympic Games. He gave the government a starchitectural structure projecting a chic, modern image of the Middle Kingdom onto the world stage. But instead of being feted by authorities, he was already a target, having used his newfound prestige to publicize the harsh treatment of migrant workers during the Olympic Games.

Ai’s discontent with both the capital and the party traces back to the day he arrived there in 1976. It was the year of a 7.5-magnitude earthquake in nearby Tangshan whose death toll was estimated between 242,000 and 655,000. Following Mao’s death a few months later, the ruling Gang of Four tried to play down the catastrophe for political purposes.

The disaster resonated with Ai during the 2008 quake in Sichuan, which left 69,000 dead. In the ensuing weeks, Ai and his team launched a “citizens’ investigation,” eventually posting the names of 5,000 schoolchildren killed as the result of shoddy “tofu dregs” building materials and lax government standards — information the government had suppressed.

The government hit back. When he was in Chengdu to testify on behalf of fellow activist Tan Zuoren, police barged into his hotel room and struck Ai on the head. Weeks later he was hospitalized with a severe headache, the result of intracranial bleeding that became life-threatening. Doctors had to drill through his skull to drain the blood.

Police installed surveillance cameras around his compound outside Beijing, and in 2011 the government bulldozed his Shanghai studio. Soon afterward, they arrested him. Ai was held in a room with two guards who never left his side, joining him even in the bathroom and standing beside his bed while he slept.

“In jail there are certain conditions where you wish to die rather than to stay alive,” he recalls. “Basically, you use life to punish life. So everything in jail is against the essential meaning of being alive.”

Coming in November: Sam Quinones, Ann Patchett, Emily Ratajkowski, Nikole Hannah-Jones, Gary Shteyngart, Natashia Deón — and the list goes on.

In his memoir, Ai details interrogations during which flummoxed questioners try to pin charges on a man who has done nothing wrong and has little to hide. He befriends his guards, generally farm boys enticed by the opportunities of military service. One secretly tells him they work for a “‘dark empire,’ forbidding in its hierarchy, riddled with corruption and filth.”

But as Ai writes, he knows he can overcome it: “Having a real — and powerful — adversary was my good fortune, making freedom all the more tangible. Limitations come only from a fear inside the heart, and art is the antidote to fear.”

Responding to pressure from the global art world, authorities eventually released Ai. But it was only in 2015 that they restored his passport, allowing him to rejoin his family in Berlin.

“It’s become a responsibility to try to honestly tell the story about where I came from and also to give that record to my son,” Ai says of the memoir. “It was very hard and took 10 years.” He has revisited his pain, but not the country that took so much from his family. “I was thinking Los Angeles was great, upstate New York, and then now I’m in Portugal. Good food, an ocean. I’m very happy here.”

Sally Rooney, Anthony Doerr, Maggie Nelson, Richard Powers, Jonathan Franzen — the list goes on. Four critics on kicking off a big, bookish fall.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.