Intersectionality is nothing new for ‘Vanguard’ author Martha S. Jones

- Share via

2021 L.A. Times Festival of Books Preview

Martha S. Jones

Jones, a finalist for the 2020 L.A. Times Book Prize in history, appears April 23 on “History: Racism and Exclusion in the United States” with fellow finalists Alice Baumgartner and Walter Johnson, moderated by Anna-Lisa Grace Cox.

RSVP for free at events.latimes.com/festivalofbooks

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

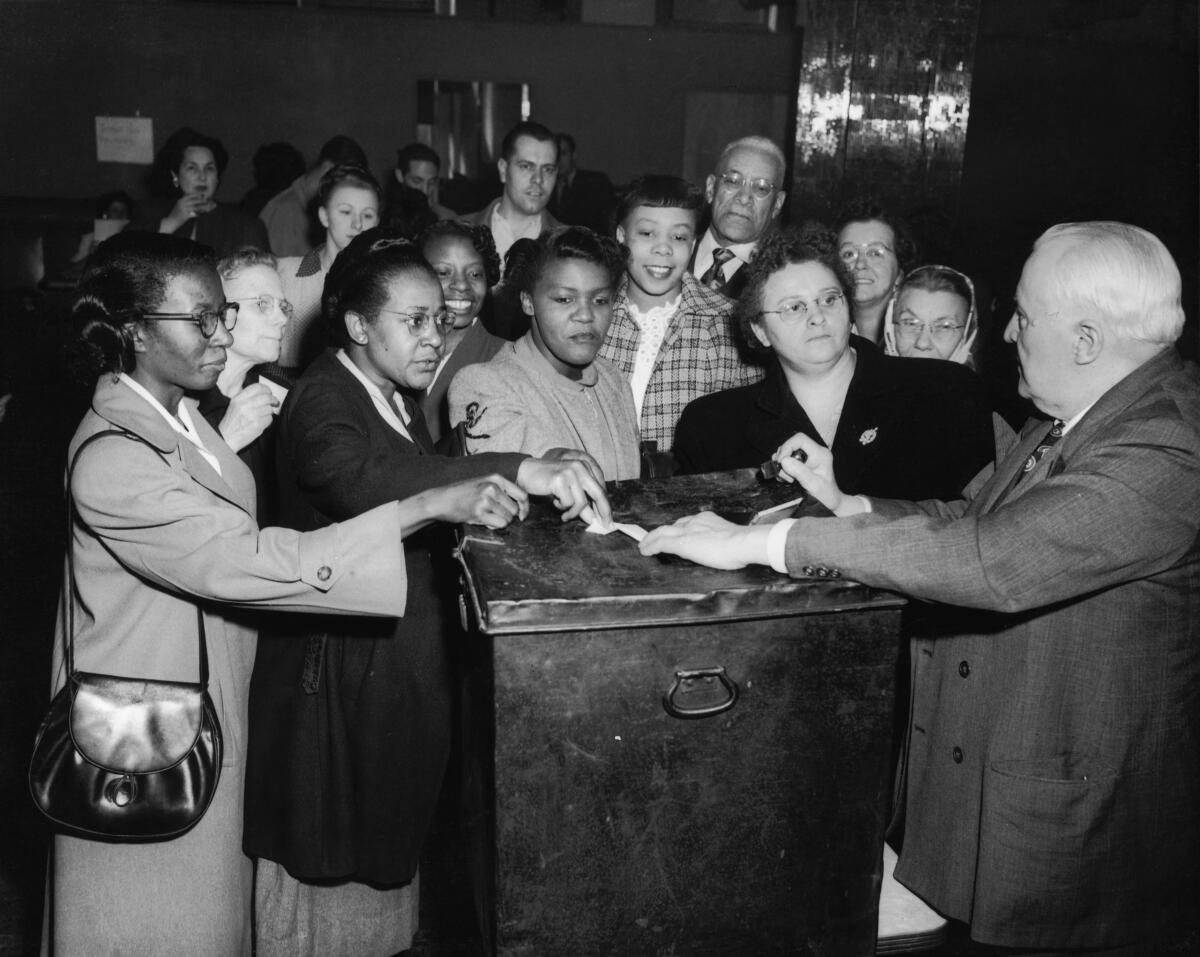

“Intersectionality” may be a modern term, but the concept of identities defining one’s place in the power structure isn’t new at all. Martha S. Jones reminds us of this in “Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All.” Her study of the vibrant history and rich legacy of Black women working toward goals both individual and universal is a finalist for this year’s L.A. Times Book Prize in history. Jones also will be a guest at the virtual Festival of Books.

A professor and legal historian at Johns Hopkins University, Jones stresses the multiplicity of not only her subjects’ identities but their work, with “one eye on the polls and the other organizing and education.” Her goal, she said, was to build an alternative feminist pantheon alongside the monuments to Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. She was thrilled to hear Vice President Kamala Harris accept her party’s nomination by citing women named in her book — Fannie Lou Hamer, Constance Baker Motley and Mary McLeod Bethune.

Did Vice President Harris read “Vanguard”?

“I can’t say,” Jones said with a hint of mystery during a video call from her home in Baltimore. She spoke to The Times about the unique place of Black women in American political history, the question of colorism and why Rosa Parks was more than just a tired woman on a bus.

Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, winner of the Times Book Prize in history, spent a decade on “They Were Her Property,” about women slave owners.

Your book arrived in 2020, a difficult time for books and for the world. What do you make of the reaction since its release?

Despite the limitations, I’ve been overjoyed. Video meetings have given me the opportunity to meet with many more book clubs and K-12 educators, an incredibly broad range of readers. I don’t know how I would have managed that if I were getting on planes and trains and automobiles.

Do any of your Zooms with students stand out?

I’ve had some very poignant moments with young readers, who have a question for me: Why did you keep this history from us for so long? It’s important to remember the possibilities and obligations in writing history. I appreciate the ways in which young people see themselves in history. It resonated very deeply with the 2020 election cycle and how we’ve struggled over history — who writes it and for whom? That’s not a question that’s going to go away. That question is a perennial one.

Sometimes it feels like the phrase “Black women will save us!” is overused. Does that statement resonate with you?

Yes. I think “Vanguard” shows how Black women supporting American democracy is nothing new. For most of that history Black women did so despite suppression and denigration. But it is also to some degree true, right? African American women have always defined and held up the high bar for American democracy. That is not an enviable task. It is a burden.

You write in “Vanguard” that “without the vote, Black Americans had to build other routes to political power.” Could you discuss some of those other routes, and how they were specifically tied to feminism?

Running through everything in my book is how Black women use the pen and the printing press to build their own platforms and join the broader political debate. If I’d told the story through a conventional historical lens, it would have been a very short book. Black women’s perspective require us to ask, what does it mean to be a preaching woman or an anti-slavery lecturer, to step into a pulpit or up to a podium, where your very presence is called into question before you even speak?

They built up their own churches and societies and organizations to create spaces not defined by either Black men’s or white women’s political concerns, frankly. Anyone who thinks “Vanguard” is a story about how Black women wedged themselves into suffrage associations, for example, will be surprised, because Black women’s organizations have a long, independent history.

Annette Gordon-Reed, Ayad Akhtar, Héctor Tobar, Martha Minow, David Kaye and Jonathan Rauch discuss the Jan. 6 riot and what we do about it.

You include photographs of the women featured in “Vanguard,” and many of them use clothing and personal style in powerful ways.

There are a couple of things here. One is the idea of taking up space. Did a Black woman have the right to be a lady? Oftentimes the answer is no, if you answer from the dominant caste’s perspective. No, you can’t sit in the ladies’ car on the train, for example. And that kind of encounter comes to define political goals for Black women who want to maintain dignity in the face of hatred.

You can’t understand these women if you don’t understand how they are fashioning political identities through associations and through fashion. There’s joy in both. My editor was initially against portraits, because portraits appear sort of conventional in books. But I made the case that these women needed to be seen in their self-fashioning. It’s part of their story.

Even when these Black women played by the dominant caste’s rules, they didn’t give up their essential Blackness, their racial identities.

Many women worked by the rules of the “politics of respectability,” but that doesn’t define who they are. Remaining at a careful distance from racism was essential to their approach to power. Rosa Parks is a wonderful example. We all hear about the moment when she refused to give up her seat on a bus. But a lot of people don’t realize she had experience in politics, civil rights and voting rights long before that moment. She was a complex and multifaceted human being, not simply a tired older woman on a bus. That story probably served a purpose at one point, but I think we’re ready for more than that.

What is the role of skin tone among the vanguard, knowing that so many at the forefront were lighter-skinned?

I appreciate this question because you’re anticipating my next book, which looks at what we sometimes refer to as colorism. My question is: How did each generation of Black women grapple with the legacies of slavery and its sexual violence? In some generations it was an open secret, then in the next it would be tucked away and deliberately forgotten because it is painful. It is feared. It’s the kind of story that, earlier in history, would have compromised women who were working to claim full citizenship and their rightful place in political life.

But again, that’s what thrilled me about Vice President Harris’ nod to the the women of the vanguard: She introduced new sheroes and sent us to do our homework. It’s the kind of work Black women have been doing for hundreds of years.

She became the national youth poet laureate at age 16; six years later, she read her poem at Joe Biden’s and Kamala Harris’ historic swearing-in.

Patrick is a freelance critic who tweets @TheBookMaven.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.