Helpless women? Not these slave owners

- Share via

It’s 1858, and a 21-year-old Tennesseean named Elizabeth Childress decides she wants to “convert into money” something she owns — a piece of property that history never previously imagined a woman like her might own, let alone be able to sell. That property? A 15-year old girl named Sally.

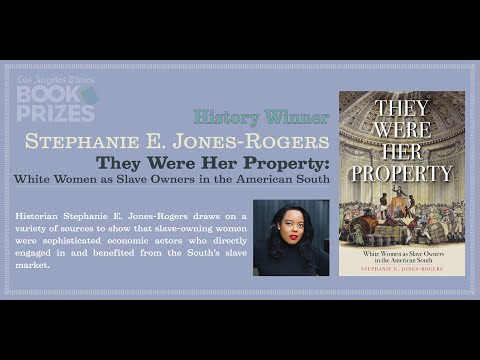

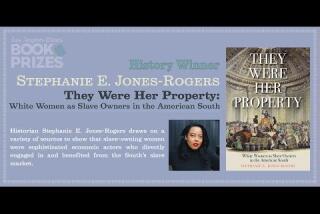

This anecdote in Stephanie Jones-Rogers’ “They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South,” winner of the 2019 Times Book Prize for history, contradicts much of our received wisdom on women in the antebellum South — that they were passive witnesses, helpless in the face of the law, lesser victims of the long, ugly reign of terror that was American slavery.

Thanks to the careful scholarship and sharp storytelling of Jones-Rogers, a professor at UC Berkeley, we now know differently. The sale of a young slave like Sally didn’t necessarily involve a husband or brother or male relative. It was completely normal for a white woman to do it all herself — a dark twist to a complicated legacy of female independence. In the above instance, the young Childress not only had the gumption to hire a “negro trader” but when the first sale fell through and the final price came in lower than she judged fair, she also took the matter to court. And she won.

It’s one of many bewildering and upsetting facets of Jones-Rogers’ book, which offers a shocking, stirring and deeply complicated new understanding of the central role white women played in one of our nation’s worst moments.

As Jones-Rogers recalled in a recent phone call from the Bay Area, it all started with a question. She was a graduate student at Rutgers in 2009, teaching a history course, when a young white female student asked what motherhood had looked like in the 1800s.

An expert in the colonial period, Jones-Rogers could have lectured about how slaves like Sally had to care not only for their own infants but also for the children of white masters. Some slaves, Jones-Rogers could say, were even known to serve as wet nurses, suckling the babes of their white counterparts. But the query inspired Jones-Rogers to ask a more specific question: Just how much and in what ways did a white woman control a girl like Sally?

The answer took 10 years of poring over the well-thumbed archives of a Works Progress Administration-era initiative called the Federal Writers’ Project, which collected first-hand accounts from actual former slaves, their children and other relatives. “It’s letters and conversations researchers have studied for decades,” Jones-Rogers said. “But I was looking — based on a new framework and a new set of questions.”

The 14 Times book prize winners, including Steph Cha, Namwali Serpell, Marlon James and George Packer, were honored in a virtual ceremony on Twitter.

Jones-Rogers began to amass a growing body of evidence — bolstered by antebellum legal documents, Confederate correspondence and numerous other sources — that suggested white women were hardly helpless observers or secret protestors, wilting on fainting couches in the salons of the American South. Rather, they were full and independent owners of slaves, deeply aware of and expert in the business of buying and selling them — and worst of all, they were fully engaged in the cruelty, invention and conniving that kept a whole people in chains.

Growing up in Newark, N.J., Jones-Rogers didn’t originally plan to study history. As a little girl, she was obsessed with creative pursuits like singing, violin and fashion. But in college, where she majored in psychology, a handful of history courses — coupled with the thrill of evidence-based whodunit reality shows like “Forensic Files” — sparked her investigative passion.

The hardest reading in “They Were Her Property” illustrates the sadism with which white women controlled their captives. They were unafraid to use the threat of bodily harm not just to keep slaves in line but also to squeeze greater profits from them. Out of both necessity and choice, white women could be even more devious than men in the brutal mechanics of corporal punishment and torture.

The example Jones-Rogers says haunts her the most is the “rocking chair” incident.

Voice cracking, the author recalled one white woman who kept her slaves at a level of near starvation, including the children. Every day, Jones-Rogers said, she left a trap, plopping a piece of candy on a dresser, so that every afternoon a young slave girl named Henrietta King saw it. “The young girl is so hungry, she can’t resist anymore,” Jones-Rogers said. When the mistress comes home, it’s gone. “She punishes the young girl by pinning her head under the rocker of her rocking chair.” The owner’s daughter joins in, beating King with a leather cowhide while her mother rocks and rocks. “For the rest of this woman’s life, she is disfigured, she causes children to cry, people to cross the street.”

It’s “a very ugly feminist story,” Jones-Rogers said, referring to this portrait of white women as powerful, independent and cruel. “But the freedom that they are able to procure for themselves is only made possible by subjugation and oppression.”

At a time of sensitive debates over whether today’s feminism is too corporate or too white — when, for example, minorities employed by go-go women’s workspace the Wing complain of marginalization and hypocrisy — Jones-Rogers’ research helps reframe and complicate the narrative. But she isn’t just speaking truth to elites or to her fellow academics: “I wanted to write a book my mother could read, and she only has a high school education.”

Jones-Rogers isn’t done stirring up the dynamics of history and feminism. Her next project will investigate the hundreds of white women from Britain who traveled on slave ships from 1680 into the 1700s, picking up captives on African soil. “What were they thinking when they heard the moans and mourning?” Jones-Rogers wants to know. And why, she will endeavor to explore, did many of these white women ultimately decide to stay in West Africa?

The kinds of details Jones-Rogers is collecting are not just shattering conceptions, deepening both the academic and popular understanding of some of the worst things we can do to one another. They also resonate on an almost cinematic level. Would she be interested in adapting any of her work for the screen? “I would love that,” she said, laughing. But, she cautioned, “No matter how much information some people have at their disposal — or that you present to them — nothing will change their minds.”

Deuel is the author of “Friday Was the Bomb: Five Years in the Middle East.”

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Keren Taylor, Innovator's Award

2:04

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Namwali Serpell, Art Seidenbaum Award

1:51

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Maria Popova, Science & Technology

3:09

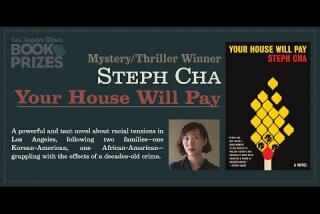

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Steph Cha, Mystery/Thriller

1:33

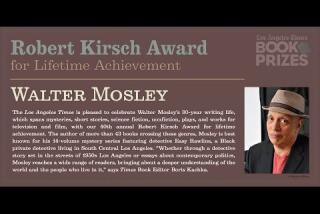

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Walter Mosley, Robert Kirsch Award for Lifetime Achievement

2:27

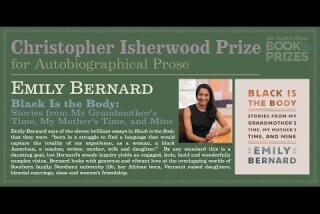

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Emily Bernard, Christopher Isherwood Prize for Autobiographical Prose

1:43

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, History

1:35

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Ben Lerner, Fiction

1:11

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Emily Bazelon, Current Interest

0:42

Los Angeles Times Book Prizes: Eleanor Davis, Graphic Novel/Comics

2:00

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.