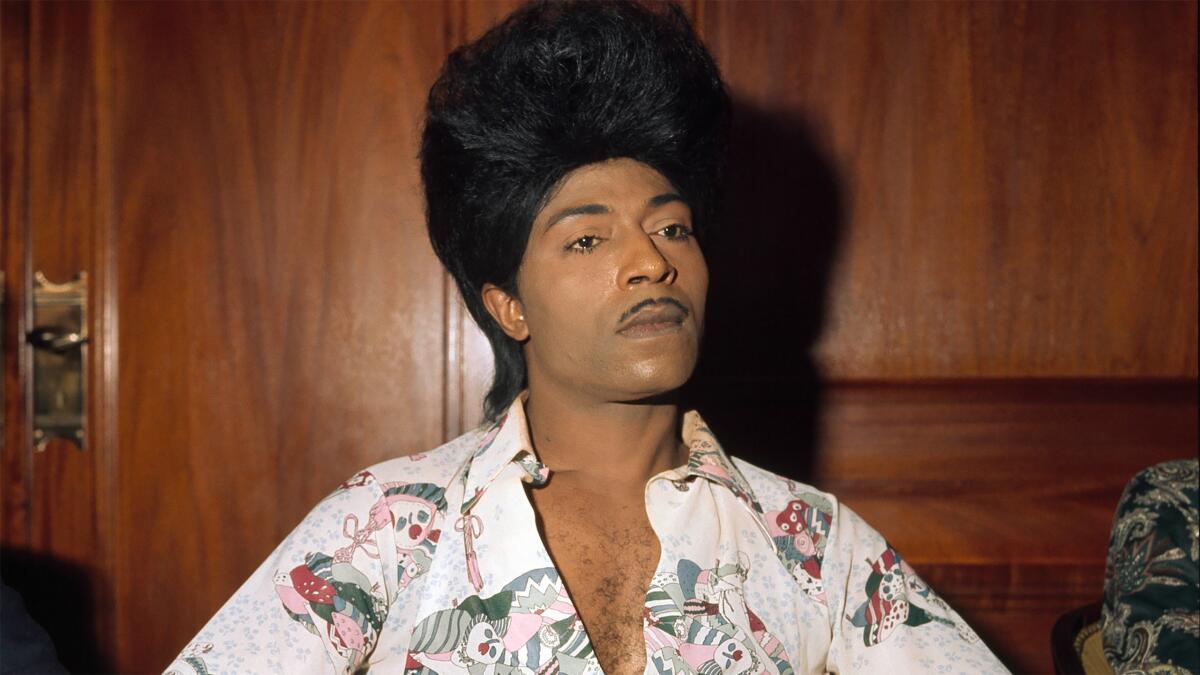

‘Spirit, rhythm and swagger’ highlight Little Richard documentary

- Share via

Filmmaker Lisa Cortés believes that if deacon’s-son-turned-rock-legend Little Richard had been whispering anything in her ear while she was making her documentary “Little Richard: I Am Everything,” it was, “There’s a lot of great music, but honor my spirit, my rhythm and my swagger.” Her electric, informative and history-correcting film does just that, portraying the ecstasy and agony of the Macon-born musician’s life as a roller coaster of innovation, liberation and erasure: what being openly gay did for rock ‘n’ roll, what the rock world never fully acknowledged, and how hard being Little Richard was as a result.

Little Richard, who died in 2020, is no easy subject to capture. Was that apparent early on in your research?

His journey is just so crazy. He’s rock ‘n’ roll, he’s in the church, he’s back to rock ‘n’ roll, he’s getting married. When you zoom out and see the social, cultural context of everything he’s starting and innovating and railing against, it defines what it means to be an icon. A lot of what was in the popular consciousness was Richard as a caricature, this comic foil. The minute you read just about the first 15 years of his life, you see he’s on this incredible collision course with history.

Little Richard, the flamboyant, piano-pounding showman who injected sheer abandon into rock ’n’ roll in its early days, died Saturday. He was 87.

Richard was always loud and proud but not necessarily a reliable narrator. How did you deal with that?

It was engaging with wonderful archival producers to pull in a lot of material, then interviews with family, friends, musicians. There was a lot more to Richard to not only excavate, but also interrogate. I wanted to give him the agency to tell his story, but I saw the need to have a counterpoint to Richard. If I’d leaned solely into Richard, there would have been inaccuracies. That’s why we have these different Greek choruses, particularly my Black and queer scholars, like Jason King and Tavia Nyong’o, brilliant folks who are able to live who they are in a way that Richard wasn’t able to but who had tremendous regard for him. They recognized he paved the way, so 50, 60 years later, you can be Lil Nas X in your fullness.

It’s heartbreaking how he could only swing like a pendulum between being out and God-fearing.

I think it’s this kind of code-switching. It started from the beginning. His father is a minister and a bootlegger. He’s going to the more sedate Baptist church, then the Pentecostal church. He’s born into the flame, so to speak, these crazy juxtapositions, and he’s never given any tools about how to navigate them. He’s at home with the sacred and the profane. So whether it’s rock ‘n’ roll or gospel, they’re equally filled with a great sense of Richard.

What do you feel like your film is saying about openness and expression in rock ‘n’ roll?

Rock ‘n’ roll is more than the music, the spirit and the icons. It’s a liberatory music. Think of how it fueled revolutions in other countries. The music is an amalgamation of some of the most intricate components of American music: gospel, soul, blues. These are born from struggle, and rock ‘n’ roll fuses them with a backbeat and a holler.

And where, as your film shows, would the Stones, the Beatles and Led Zeppelin be without his influence?

Led Zeppelin’s “Rock and Roll” takes the drum pattern from “Keep A-Knockin,’” and the reason why Richard’s drum pattern is so amazing is he took his drummer to the segregated train station in Macon. He said, “I want you to listen to the rhythm of the train. That’s what I want you to play.” That’s why there’s a close-up of that train station with the Colored waiting room, and we hold on that. It’s a part of our reckoning with this collective history that collides in this man.

You also deploy this visual motif of Richard’s influence being like dust particles through time, and dream sequences with musicians like Valerie June playing rock pioneer Sister Rosetta Tharpe. What inspired that?

His arrival on the scene was elemental, like the Big Bang. The idea of particles was something we talked about as embodying that energy. There was a great desire with this film to be immersive, to access emotionally what he’s going through. There are certain conventions that come with the music doc, but this is Little Richard, man! I wanted to break the fourth wall about what a music doc is supposed to be. I’m a huge fan of magical realism. Maybe it’s because I’m half-Colombian! I’ve read too much Gabriel García Márquez.

At a certain point, did you sense Little Richard collaborating with you from the beyond?

Absolutely. His spirit, I would like to believe, is quite happy with the fullness of the picture. And people who were incredibly close to him? They said, “Richard would have liked this. It feels like knowing Richard.”

What about reactions from moviegoers unaware of his importance?

A man came up after a screening, an older white man, he thanked me and said, “Every time I see docs about people who look different from me, I get really angry about the history nobody told me about. Because we actually need to know.” With Little Richard, you think it’s about this individual, but it’s about the world he inhabited and changed. It’s a much larger cultural conversation.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.