- Share via

ON THE U.S.-MEXICO BORDER, San Diego — I’ve done the drive from Orange County to the United States-Mexico border so many times that it’s as easy to describe as my backyard.

Start in Anaheim if I’m taking my dad, Santa Ana if it’s my wife. Slow down at the Border Patrol station in San Clemente, even though all the agents are on the northbound side and I’m an American citizen — because you just never know.

Try to sneak a peek at Camp Pendleton’s natural beauty and military installations. Take the 805 South to avoid downtown San Diego. Zip through suburbs, working-class communities, rolling hills and all sorts of Spanish-named streets until reuniting with the 5 in San Ysidro.

Cross into Tijuana. Fin.

It’s such a familiar journey that I rarely think of it as what it is — a trip to another country. It doesn’t take more than two hours, but it might as well be an eternity.

The border was drawn 175 years ago by a joint U.S.-Mexico commission after the U.S. won the war between the two countries and conquered what is now the American Southwest. Both sides of la frontera have been picking at this open sore ever since.

Voters will go to the polls in less than three weeks, ears ringing with rhetoric from Democrats and Republicans alike about this border and what the migrants who cross it represent for the future of this country.

Meanwhile, political pundits and journalists are fretting over another question: What will Latinos do?

Seven days. Seven states. Nearly 3,000 miles. Gustavo Arellano talks to Latinos across the Southwest about their hopes, fears and dreams in this election year.

As the child of Mexican immigrants — my mom arrived legally, my dad came in the trunk of a Chevy — I have dealt with American suspicion about Latinos and especially Mexicans, personally and professionally, for most of my life. The ignorance — yes, we assimilate, and no, we’re not sleeper agents hell-bent on retaking the American Southwest through demographics and enchiladas — mostly amuses me when it doesn’t offend.

That’s why I initially rolled my eyes when my editors suggested a road trip to ask Latinos whom they plan to pick for president, when “our” votes can make or break a candidate as never before.

The “Latino vote” is a tired trope, I argued. It’s an insulting one too. To say there even is such a thing reduces a wildly diverse group into a trite narrative that I’ve spent my career trying to debunk, when not ridiculing it altogether.

Latino disenchantment with the Democratic Party, the growing numbers of us who support Donald Trump, our emerging power in swing states — I’ve covered all of this ad nauseam over the last eight years. I was in no mood to go down those same trails along with the rest of the national media.

But the more I thought about it, the more a road trip intrigued me. What better way to show what I’ve known forever but that many Americans refuse to even consider — that Latinos are as American as anyone else, if not more so? That although we pay attention to politics, we care more about local issues than the electoral horse race?

That’s why I found myself on a Wednesday morning, a week before the Democratic National Convention, headed down to the border.

Over seven days and nearly 3,000 miles in a small but sturdy Nissan Versa rental, I visited Mexican American communities across the Southwest, the region the U.S. took from Mexico by conquest. Here is where American fears about Latinos first hardened — and here is where we made a life for ourselves, haters be damned.

I went to copper country in Arizona, where my family’s American tale began, and El Paso, long a migrant hub but nowadays depicted by right-wingers as a place of invasion, chosen by a gunman who wanted to “remove the threat of the Hispanic voting bloc” as the place to massacre 23 people.

I drove through New Mexico, where Latinos have farmed since before the Pilgrims landed on Plymouth Rock, and spent time in tiny Antonito, Colo., home to the oldest Latino civil rights group in the country.

Some of the most important names in L.A. Latino politics were born in Arizona mining towns or traced their lineage there. I share those roots.

In Colorado Springs, I dropped in on a Mexican American couple famous for their beer and now called heroes for their role in ending the 2022 Club Q massacre.

Sunflowers in Utah. Do-gooder college kids turned elected officials in Las Vegas. Cousins making historically significant tacos while fending off internet trolls in San Bernardino.

I found humor, I found grit. I found hope. I found a people thriving — and mostly ambivalent about this country’s partisan divide.

Who’s the next person in the White House matters — but not as much as what’s in front of them.

The border wall begins at the Pacific Ocean, bisecting the half-acre Friendship Park. First Lady Pat Nixon presided over the park’s dedication in 1971, crossing a barbed wire fence that separated the two countries to greet cheering Mexicans on the other side.

“I hope there won’t be a fence here very long,” she told the press.

Instead, California and other states passed anti-immigrant laws, as migration from Mexico increased and Central Americans also began to cross over. The U.S. built a succession of border walls, each higher and sturdier than the last. The feds added a second, interior barrier in 2011, yet Friendship Park remained a space of unity.

Murals adorned the wall on the Mexican side. On the American side, activists set up a garden with native plants. People could talk to one another through the wall and even touch through the mesh fence American authorities eventually set up. Once a year, la migra opened a gate so separated families could embrace in a designated space for about half an hour.

At the end of 2019, the Border Patrol shuttered the American side of Friendship Park for what it said was a construction project. Last year, the Biden administration replaced the 18-foot-tall secondary fence with a 30-foot-tall one. The park has never reopened.

My drive down the 5 Freeway had been uneventful save for an exit I had never noticed before: Tocayo Avenue.

In Mexican Spanish, the word signifies “namesake” and is exclaimed with pride — ¡Tocayo! — when two people with the same name meet. It’s a way to proclaim that even though you’re strangers, you share something that binds you forever.

The United States and Mexico are tocayos, I thought, even if they’ll never admit it.

From the Tocayo Avenue exit, I passed through large ranches and gorgeous stretches of estuary. It was a beautiful drive, until I saw signs hanging from fences and telephone poles that proclaimed: “Keep the sewage in Mexico. Stop the stink!”

The reference was ostensibly to the polluted Tijuana River — but I couldn’t help thinking that Trump and his followers would approve.

That morning, the closest vantage point for the border wall was closed because of the river pollution.

Instead, I hiked up a gravel road with Adriana Jasso and her friend Nanzi Muro. I wore slacks and sneakers, because I’m no hiker. Jasso offered me water, sunblock, a hat and an orange, but I declined.

Fifty years ago, my dad ran through these hills, back when they were far less patrolled. In a decade of crossing and re-crossing, Papi treated the border and the fences that demarcated it like an exercise in prepositions: He went around it, through it, above it, below it, past it. So did his siblings, my grandparents, cousins, friends and hundreds of people I’ve known, all to make a better life in the United States.

That’s why I can never hate anyone who does the same thing, for the same reason. The least I could do was tough out a hike for an hour.

We walked underneath big trees and through coastal scrub, past a roadside memorial for a migrant and a Border Patrol truck with no one in it. A military helicopter circled above.

Jasso, a member of Friends of Friendship Park, which takes care of the park’s American side, went over its history as the sun baked us.

“Christmas parties, yoga classes, English and Spanish classes,” recalled Jasso, who was born in the Mexican state of Guanajuato. “Food for everyone on either side. The fence was just something that was there.”

Activists had to ask for permission from the Border Patrol to hold events, but Jasso said they almost never had a problem until Trump. In September 2018, then-U.S. Atty. Gen. Jeff Sessions appeared at Friendship Park to announce a zero-tolerance policy that included separating migrant children from their parents.

Visions of combo platters and glorious tacos filled my mind as I barreled down the 15. The only election reminder was a “Viva Trump” sign outside Victorville.

After about half an hour, we reached our destination: a hilltop marker declaring we were about to enter federal land monitored by the Border Patrol.

Down below, excavators, cranes and graders were building a bluff where a new border wall will join an existing 30-foot wall the Trump administration spent billions of dollars to erect. Behind the construction site was Tijuana; in front of it was an interior wall that will also be replaced. The scene looked like “Minecraft” come to life, with human misery the prize.

This year, Jasso attended a meeting at the White House where she and other activists pleaded with Biden administration officials to reopen Friendship Park.

“I think the reason why they keep it closed is there is something to be said about a space that brings together families,” Jasso said as we hiked back to our cars, bitterness in her voice. “And now that the border is front and center in this election, you just can’t have that.”

Jasso, who helps run the American Friends Service Committee’s border program, suggested we head over to the group’s field camp. It’s set up against the interior wall that runs parallel to the actual border wall. A massive gate in that interior wall looks like something out of a medieval castle — all that’s missing is a moat and guards.

1

2

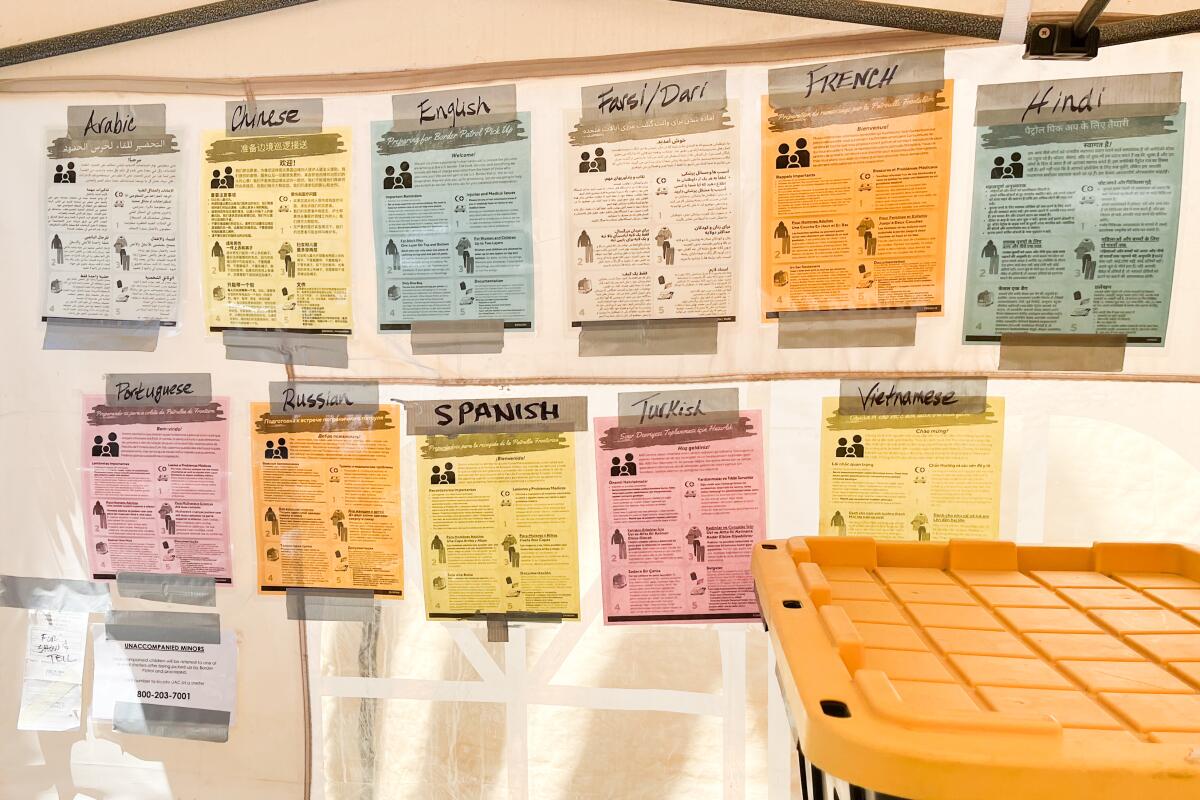

1. Health notices in different languages at a field camp run by the American Friends Service Committee at the border in San Diego. 2. Supplies for migrants at a field camp run by the American Friends Service Committee that is set up next to the border fence in San Diego. (Gustavo Arellano / Los Angeles Times)

Tents held bins packed with food, clothes and medical supplies. But I couldn’t stop staring at the wall. I had never seen it up so close. It was … ugly.

Rusted brown metal. Tall but not insurmountable. Cheap. A joke.

This country has so many problems, so much division — and a big, ugly wall is supposed to solve something? Shame on Trump. Shame on Joe Biden. Shame on Kamala Harris, who in late September near the border in Arizona bragged about how she’ll be better on “border security” than Trump ever was.

Immigration is a top presidential election issue again in 2024, as Republican Donald Trump and Democrat Kamala Harris espouse starkly different approaches to managing the border.

Jasso said that every morning, Border Patrol agents tell migrants who have scaled the first border wall but were caught before crossing the second to head to the Friends camp. Through the slatted wall, volunteers provide them with clothes, medical supplies and snacks — even free WiFi and an electrical strip to charge their phones. The agents eventually open the gate and take the migrants away for processing.

The Friends had assisted 15 people earlier that morning. But no one arrived while I was there. Biden’s executive order in July that severely limited asylum claims has caused the number of migrants to drop dramatically, Jasso said.

She showed me a daily log of the people who have passed through, including their arrival times and countries of origin. Colombia, Jordan, Dominican Republic, Ukraine. Mexico, of course.

“If Americans saw what we saw, they would feel different about this so-called crisis,” Jasso said in Spanish. “There’s a saying in Mexico: The heart cannot feel what the eyes cannot see.”

I left somewhat disappointed. For decades, I’ve heard that the border is little better than a sieve through which millions of migrants easily pass. I hadn’t seen one.

There was one more immigration hot spot I wanted to check out: Jacumba Hot Springs, an hour and a half away in eastern San Diego County.

Last fall, hundreds of migrants had arrived there with little more than the clothes on their backs. Activists provided them with food and makeshift shelter as some waited for days for Border Patrol agents to take them away. Conservative media and politicians depicted it as a full-scale invasion.

Agriculture, which intersects with key issues — the economy, climate change and immigration — is a barometer of where a region and its people are heading.

The border wall stretched all the way to the rocky horizon, with only a portable toilet disrupting the view. I saw no migrants here either. Or anyone, really: The temperature hovered at 105 degrees. The entire town seemed to be taking a siesta.

No one would trek through inhospitable terrain, far away from home, just to be a burden on a new land. My dad didn’t. His brothers and sisters didn’t. The new migrants don’t.

Sadly, more and more Latinos don’t feel this way. They want the new migrants out of here.

I merged onto Interstate 8 and sped off to Arizona. The wall lunged farther and farther south until it disappeared. Every 60 miles or so, I saw a Border Patrol vehicle stationed underneath a freeway overpass. Waiting.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.