Remember Marineland? Do you know the whole story?

- Share via

How’s your summer going?

Been attacked by any seagoing creatures? Lot of that going around.

If you happened to be boating off Spain, or yachting off the Shetland Islands, there’s a slight chance your vessel got rammed by orcas. Maybe you were swimming off the coast in the Sea of Japan, and a bunch of dolphins — those ocean-going teddy bears — set upon you.

Perhaps you were surfing off Santa Cruz and that furry bad girl who goes by the official name of Otter 841 jacked your board right out from under you, and tore off a piece of it just to prove that she has as many teeth as you do, and her bite is four times stronger than yours, so yes, she is the boss of you.

That’s what those animals are up to. And a great many of us landlubbers are cheering them on — quite the swing in sentiment since “Jaws” made us all rethink our relationship with the ocean’s murk.

Nearly 50 years ago “Jaws” — and its tagline, “You’ll never go in the water again!” — made humans specifically shark-phobic and generally ocean-critter-phobic. No measure of reason or statistics — that you are, say, 2.4 times likelier to be killed by a high-velocity Champagne cork in France alone than murdered by a shark anywhere in the world — could divert us from the ominous, two-note shivers of the “Jaws” theme.

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

But “Free Willy” and “Blackfish,” “Shark Tale” and “Finding Nemo” turned us into a human rooting section for the fish, and especially the mammals with the nickname of “killer whales.”

It’s understandable, as climate change is boiling some ocean waters into fish stew, that we should endow these creatures with conscious motive, and cast them as heroes acting in self-defense on this small, small scale against the human species that is destroying their habitat and killing their friends and relatives.

On Twitter — excuse me, Elon: X — one user posted a photo of a farmers market find — a bowl painted with an orca and the text: “They are orcanizing.” The killer whale holds a sign: “Eat the rich.”

Some scientists are waving off these incidents as clumsy and over-energetic orca play. But on the site LiveScience, Alfredo López Fernandez, a biologist at Portugal’s University of Aveiro and co-author of a paper last year on orca-human behavior, suspects that a trauma to the orca pod’s leader — say, an injury from a ship rudder or illegal fishing — may have started the behavior, and other orcas picked it up. “The orcas are doing this on purpose. Of course, we don’t know the origin or the motivation, but defensive behavior based on trauma, as the origin of all this, gains more strength for us every day,” López Fernandez said.

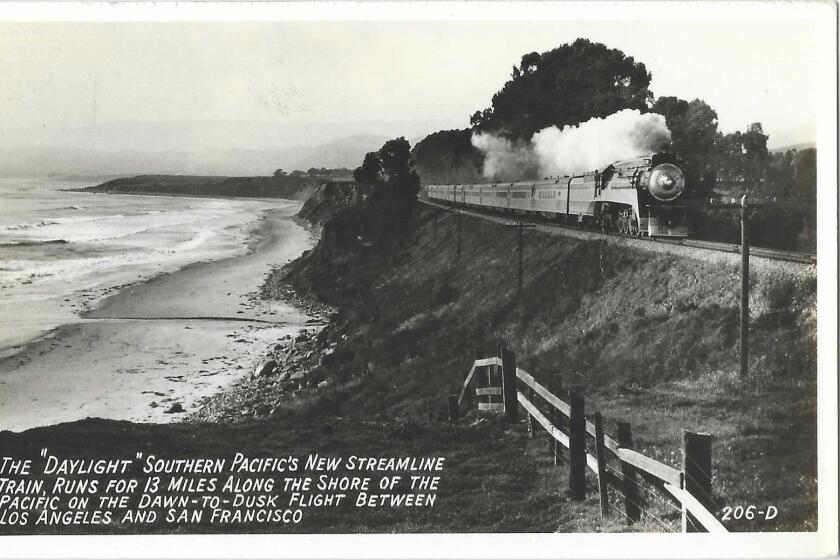

The beauty of train trips used to be a key selling point. But with the Pacific Surfliner suffering the effects of climate change, safety and reliability may trump the pretty view.

Every uprising has its origin story, and Los Angeles may be part of the orcas’.

On the Palos Verdes Peninsula, where Tongva settlements flourished for several thousand years, there’s a spectacular part called Portuguese Bend, named for the Portuguese whaling station that operated there more than 150 years ago, when gray whales were hunted so relentlessly that soon there were almost none left to kill.

That’s some bad cetacean karma.

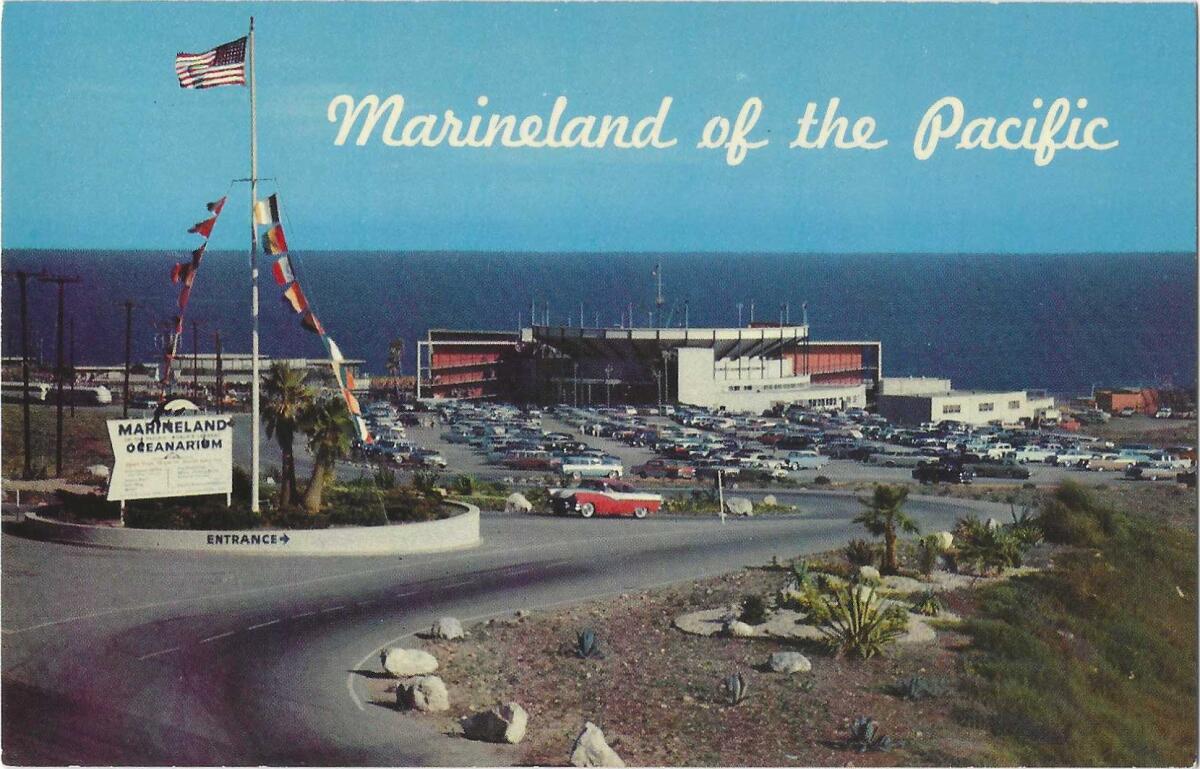

Then, about a hundred years later, on those cliffs above the ocean, they built … an ocean in miniature.

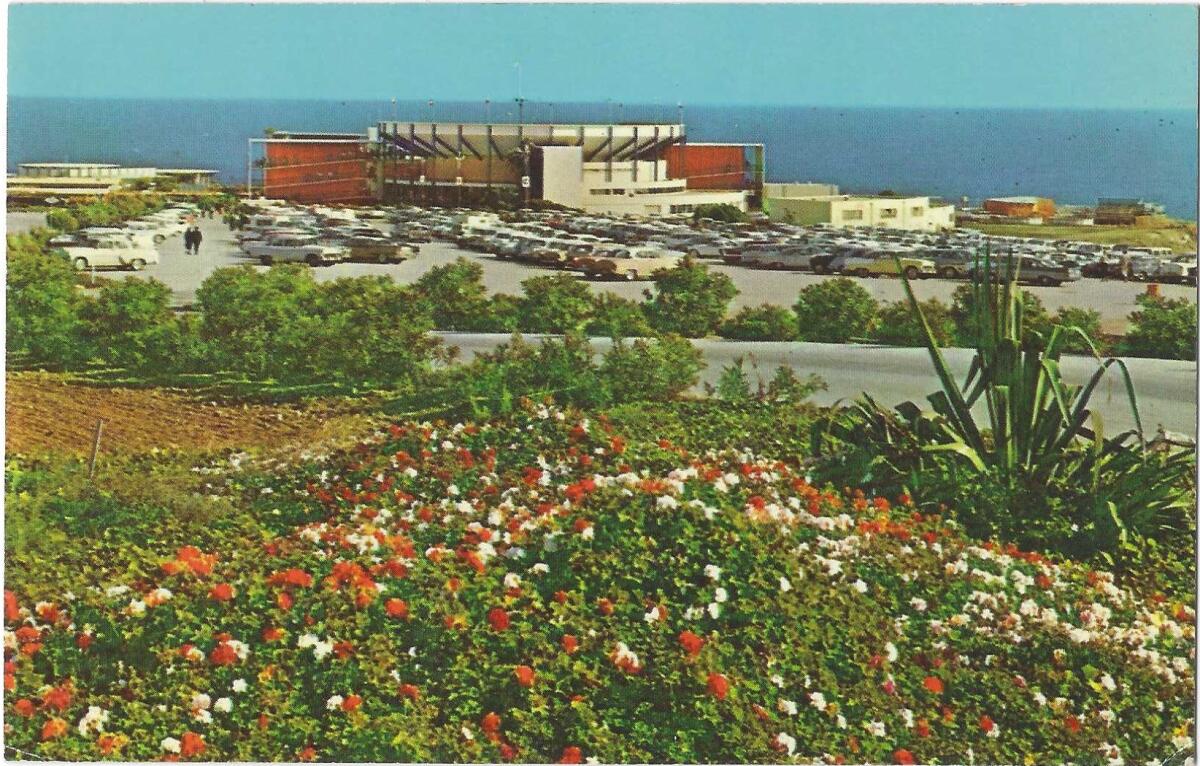

In 1954, a year before Disneyland opened in Anaheim, Marineland of the Pacific inaugurated its “oceanarium” theme park, with a 12-year-old girl, “Alice in Marineland,” cutting a fishnet instead of a ribbon.

It was in truth more of a circus, with water tanks instead of rings, where captive marine mammals and other seagoing creatures were trained to do tricks for admission-paying human audiences. It even called itself a “4-ring sea circus.”

Through the 1970s, the Sunset Travel Guide to Southern California wrote of Marineland that, “Though the aquariums and sea collections are impressive, entertainment is the first purpose of this well-known Palos Verdes show place.”

This was the second golden age of Southern California amusement parks, after our turn-of-the-century playgrounds.

Marineland was quickly followed on by Disneyland, Knott’s Berry Farm’s ghost town, Pacific Ocean Park, the modern-era Universal Studios tour, Lion Country Safari, Magic Mountain — the fortunes of each falling or rising in tempo with public tastes and economic dips and shifts.

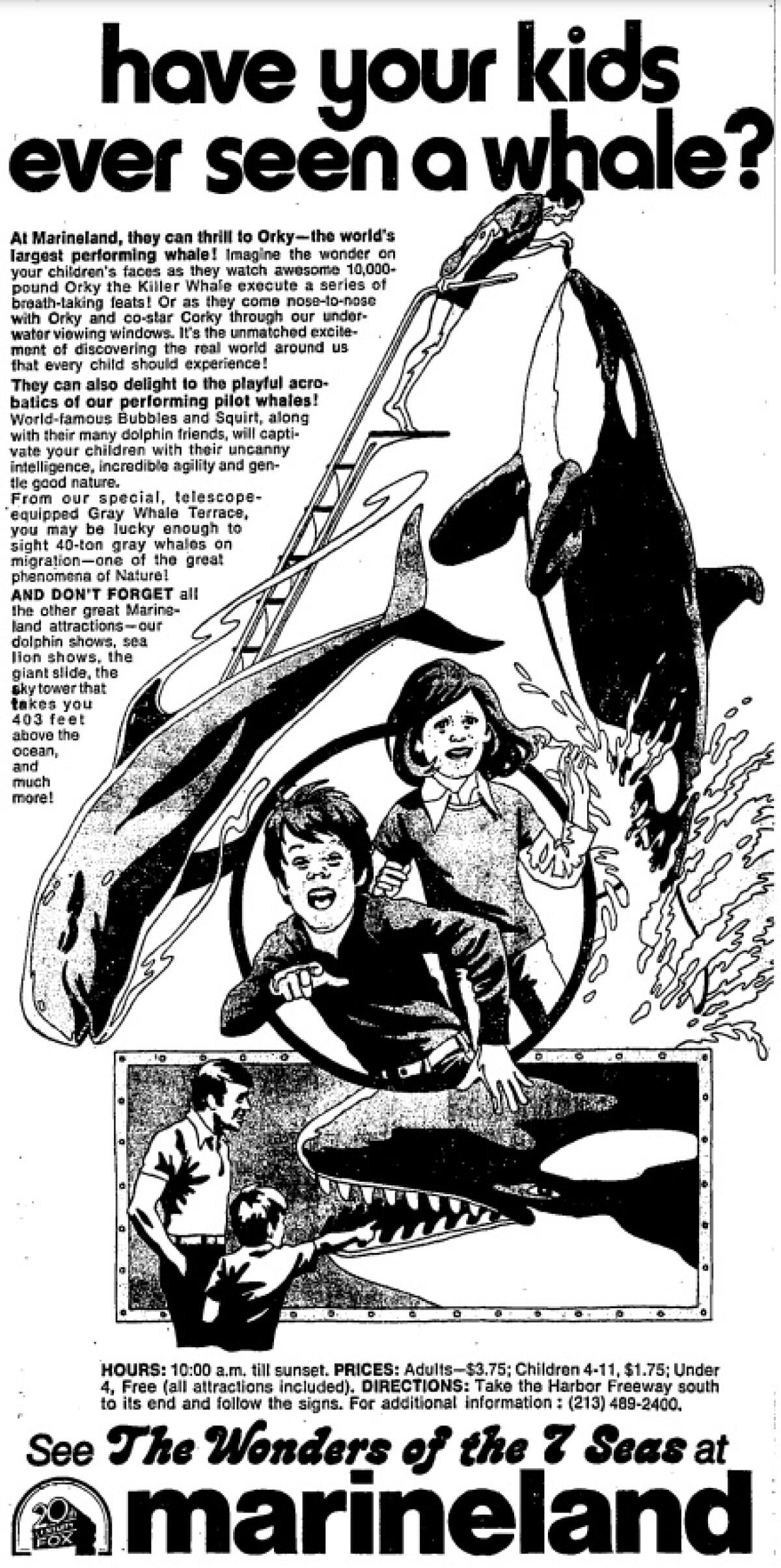

Schools sent kids to Marineland on field trips, and colleges made connections for their marine biology students. Yet by 1972, Marineland’s attendance was flagging. There seemed to be no idea it didn’t try: a new paint job and graphics, a “giant Alpine snowslide” made of Fiberglass, a pirate training school for sea lions.

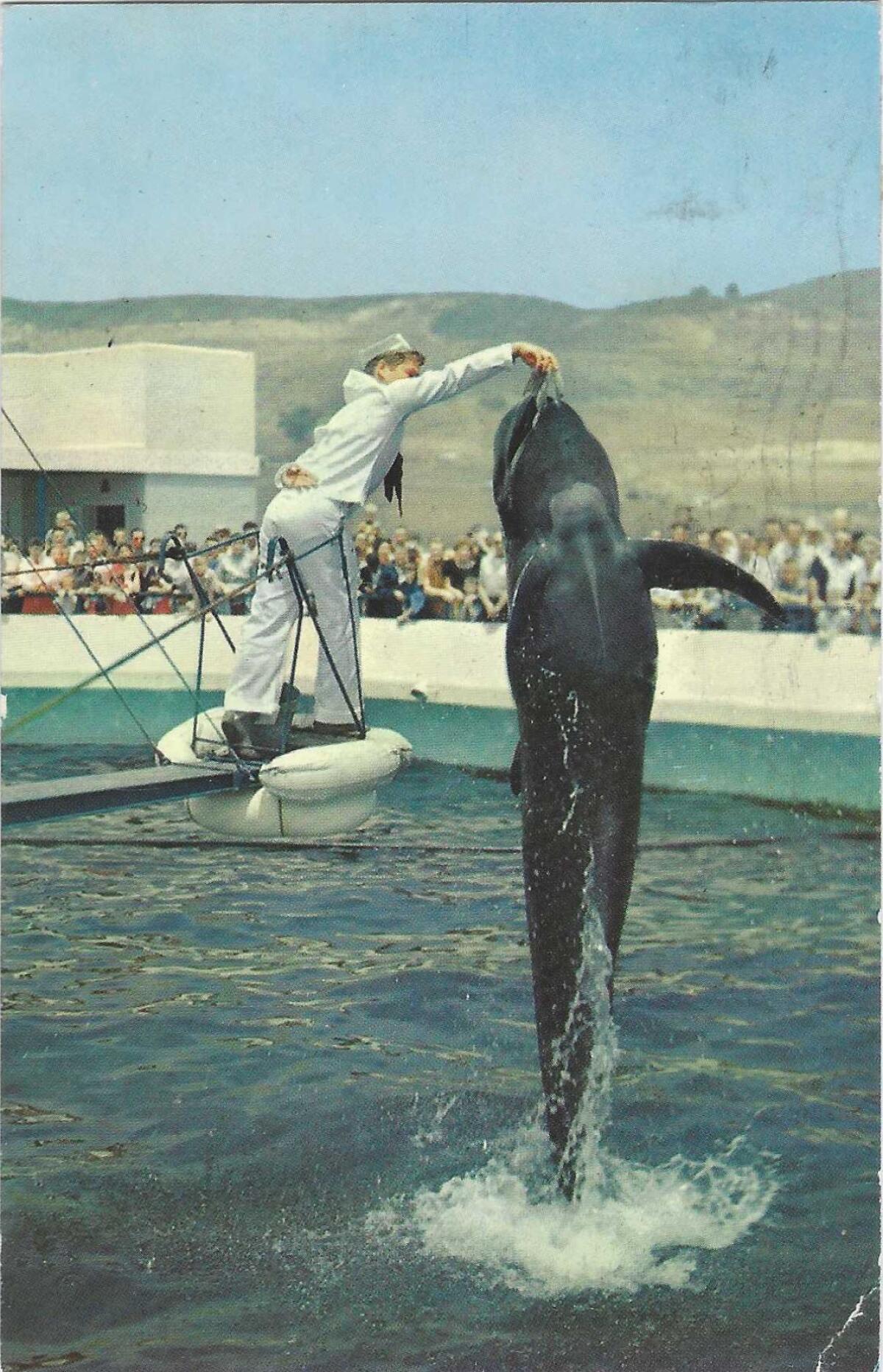

New Marineland owners cycled through, but what remained were its stars: the orcas Orky and Corky. Marineland’s original orca pair, Patches and Kenny, died at Marineland just a couple of years after their capture off British Columbia.

The freeways, the smog, the people, the culture, the intellect — nothing and no one is spared when it comes to people from New York and elsewhere insulting Los Angeles.

Marineland’s first orca was a happenstance resident. In 1961, Wanda was spotted swimming off Newport Beach, far from native waters. A Marineland “collection crew” was dispatched, and chased her to exhaustion, netted her, and trucked her to Marineland. Spectators to the pursuit had cheered Wanda every time she eluded the captors. She died less than two days later, swimming frantically, “encircling the tank at great speed and striking her body on several occasions,” Marineland staff wrote, until she convulsed and died.

In late 1986, a book publisher — Harcourt Brace Jovanovich — bought Marineland, pledging to keep it going and even spiff it up. About six weeks later, HBJ abruptly closed Marineland.

It looked an awful lot as if HBJ had bought Marineland just to poach Orky and Corky for its other marine theme park, SeaWorld in San Diego. SeaWorld needed orcas. Five had died in one two-year space, and when one dead orca was carried out of the park in the 1980s, The Times said that the trainers were under orders to shake the dead orca’s fins so that anyone who happened to see it would think it was still alive.

The regulatory net had been tightening around capturing orcas in the wild, and going out and capturing more orcas wasn’t in the cards. So Marineland’s new owners — the publishing company that had once operated a chain of seafood restaurants -- arranged a midnight move for Orky and Corky down the San Diego Freeway under police escort.

Their story was that the CHP insisted on the nighttime move for the public’s safety, but on the Palos Verdes Peninsula, and in Times letters to the editor, the muttering was about hoodwinking and betrayal.

The move was reported lightheartedly in the news — “Off to Sea World to Frolic.” But it was ghastly. First, Orky was put onto a special stretcher, and Corky — who had shared the tank with him for 18 years, and with whom she had six calves, all of whom died — tried to throw herself onto the stretcher with him. As The Times wrote, when the crane lifted Orky hundreds of feet up and then lowered him into a travel tank on a flatbed truck, “the sounds of her desperation filled the hollow tank. Orky responded with a cry [the trainer] had never heard before.” The public didn’t hear or see any of that.

Orky died at age 30, after 20 years in captivity. Corky has spent all but about five of her 50-some years in captivity.

With Corky and Orky and other sea creatures shipped off to SeaWorld, HBJ closed the park and then sold Marineland’s to-die-for-gorgeous 102 acres to a developer who had, as they all do, many plans, none involving keeping an aging marine park afloat.

This Malibu photographer captures images of great white sharks along the Southern California coast, many just feet from unknowing swimmers and surfers.

The land was sold and bought and sold again, until the developers of the Terranea luxury resort finally put shovels in the ground in 2007. The golf resort shares the peninsula with Donald Trump’s golf course; some people have conflated the two. “Terranea is not owned by or affiliated with Donald Trump or Trump Hotels,” someone from the resort blandly wrote in 2019 — in response to a tweeted slam about “crappy haired prez #45.” “We hope you will consider being our guest.”

I went to Marineland just once, on assignment. And once was enough. As a kid, I was creeped out by Charlie, the tuna in the StarKist ads, eager to volunteer to be killed for sandwich filling. Just as creepy to me was the mural on the Farmer John slaughterhouse in Vernon, a bucolic panorama of happy piglets gamboling with kids and sleeping under shady trees — a gory dissonance to the daily assembly-line killing of thousands of pigs inside the abattoir. Farmer John closed the site this year, and its land was sold to a property developer. The world has not yet gone vegetarian, but as with wild animal parks, tastes and sensibilities change.

My assignment at Marineland was in August 1984, during the L.A. Olympics, when I was writing about the outstanding Romanian gymnast Nadia Comaneci. Marineland had been put on her R&R itinerary, and I sat in the bleachers, watching her watching the display of dolphin gymnastics, and watching the crowd watching her. Maybe she was mentally scoring the performance. Marineland tried to coax her to go along with what would have been a PR coup, getting her into a swimsuit to snorkel in the water, but she sensibly refused.

Most of the whales and dolphins you remember from Marineland are long dead, but perhaps 55 orcas remain in captivity worldwide, 18 of them in the U.S. parks belonging to SeaWorld, whose website emphasizes its work rescuing and rehabbing marine wildlife. One orca, who has been in captivity in a Miami amusement park for more than 50 years, may soon go free. (A few days after this column first published, the orca died.)

The kind of capture practiced decades ago is banned now under strict federal regulations and even stricter California law, which effectively put a halt to the breeding and entertainment shows of yore. What was family fun in the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, came to seem grotesque and cruel, and movies like “Free Willy” helped to change those attitudes.

As for the present generation of seagoing avengers, I’d like to anthropomorphize them enough to think they’re so sick of being the objects of miserably hokey puns — “a whale of a tale,” and “you otter be very afraid” — that they’re slowly working their way through the human population toward the writers who commit them.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.