Opinion: This captive orca might finally go free. Why did it take so long?

- Share via

After five decades of performing at a Miami tourist attraction, the captive orca Lolita is finally on track to return to her native waters in the Pacific Northwest. Her path to freedom inspires hope — but also shows how far humans have to go in truly respecting animal life.

Born circa 1966, Lolita was a female member of the L pod, one of three southern resident orca groups living in the Pacific waters of the Salish Sea. In 1970, during a contentious capture in Penn Cove in which several orcas died, she was forever taken from her family.

Since then, Lolita — a.k.a. Tokitae in a Coast Salish language, sometimes shortened to Toki, or Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut, the name given to her by the Lummi nation — has spent more than 50 years penned in at the Miami Seaquarium entertainment park. Last year the Seaquarium, under relatively new ownership by the Dolphin Company and amid mounting public pressure, announced that Lolita has been retired from performing. Then a few months ago, the Dolphin Company signed a historic, legally binding agreement with Miami-Dade County and the nonprofit Friends of Toki (doing business as Friends of Lolita) to return this orca to a sea sanctuary in her home waters of the Salish Sea. Under the current plan, which is contingent on the receipt of government permits and regulatory approvals, it will take up to two years for Lolita to be relocated.

Killer whales have reportedly attacked more than 500 boats in European waters recently. Are they exacting revenge for humanity’s treatment of orcas?

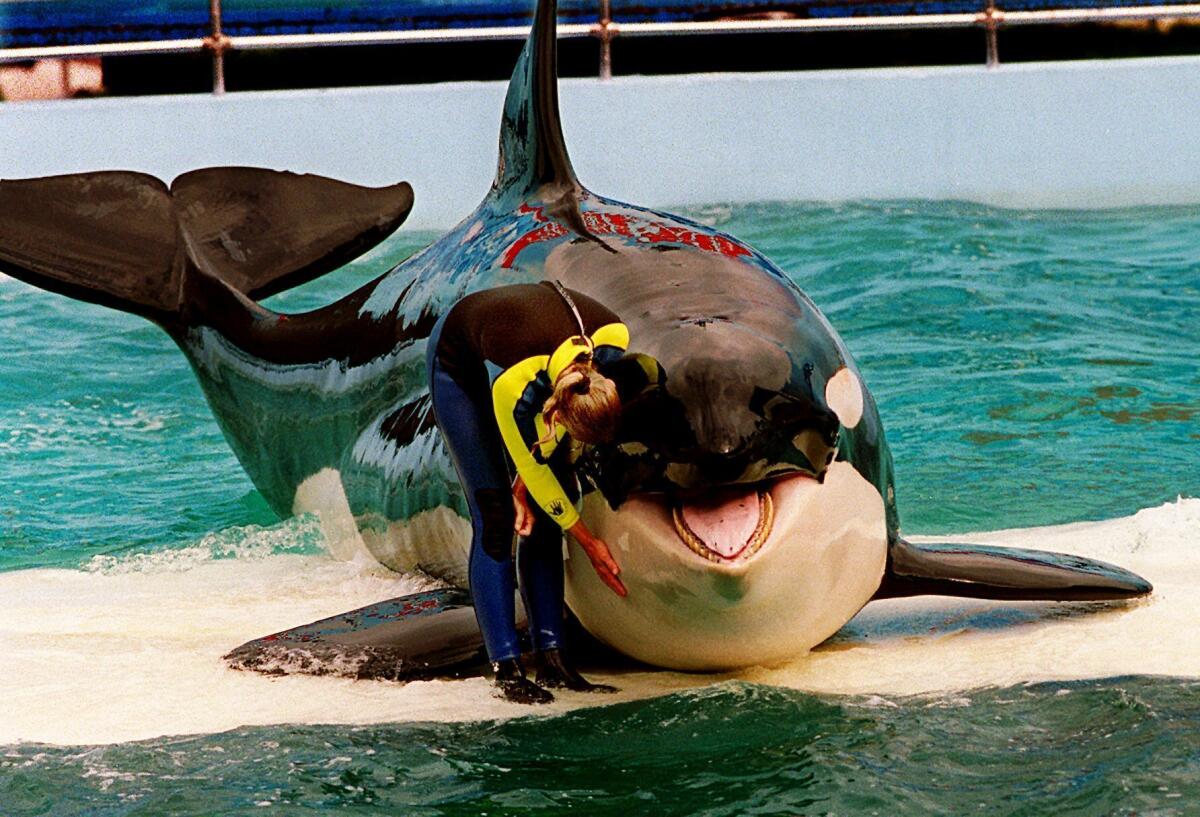

Lolita, for me, is more than just a cause or a “killer” whale. In 2016, when this orca had just passed half a century in age, I visited the Miami Seaquarium with a marine mammal vet and an ex-dolphin trainer. As a behavioral ecologist who has studied cetaceans in the wild for 30 years, I was asked to observe and record Lolita’s behaviors. The goal of our visit was to provide expert testimony on her physical and mental status in a legal action brought to compel her gradual reintroduction into her native sea.

Soul-crushing is the only way I can describe my time in Lolita’s company. Since her cage-mate Hugo died in 1980 from a brain aneurysm, likely the result of tirelessly hitting his rostrum against the walls of their under-sized pool, Lolita has had no contact with other members of her species. She was lonely, except for a couple of Pacific white-sided dolphins she shared her small tank with, unshielded from the scorching sun, deprived of environmental enrichment and forced to perform daily in a pool so minuscule she could barely swim.

There was little left in Lolita reminiscent of the wild orcas I have observed swimming free in the Pacific Ocean. With her collapsed dorsal fin she swam in seamless circles, dragged her flukes on the bottom of the pool or spent extended amounts of time underwater, motionless and facing the wall. She repeated the same behaviors, with no obvious function, over and over.

I was allowed to approach Lolita just once at the Seaquarium, and our eyes met for a heartbreaking instant. I was overpowered by the sense of hopelessness that this animal was able to convey. A couple of years later, when the appeals court in Lolita’s case ruled to keep her captive despite our — and many other people’s — efforts to free her, the thing that I remembered above all else was her suppliant, dispirited eyes.

We need a new approach to animal rights that centers on their freedom to act — not just protecting them from harm — to save them from injustice.

I still wonder how the jam-packed audiences clapping and praising Lolita’s shows could not perceive what I saw during my time at the Seaquarium: a creature severely scarred, inside and out. I wonder if it’s our human ego, sense of superiority to other beings or even desire for convenience that makes us ignore the effects of captivity. Maybe it’s just a lack of knowledge of what these animals are all about.

Lolita may never be able to thrive in the wild with her own species anymore. But as long as her health allows for her safe transfer, she must be released. In a sanctuary and under human care, she would at least have a last taste of freedom.

Intelligence and emotion in Lolita and other animals are difficult not only to define but to understand and gauge. Just think about how tricky it is for any of us to fully apprehend our own human thoughts and feelings on an everyday basis.

But it’s enough to spend time with wild dolphins, for example, to see they are capable of vivid experiences and emotional lives. Orcas are known to have their own culture. Lolita’s brain, like yours and mine, is equipped to feel anger, pain, joy, frustration and more. She is a smart, social being. And across the animal kingdom, not a day goes by without new discovery of other nonhuman creatures doing remarkable things.

Now is the time to recognize that we are not the only species able to feel and think. It’s the only road to developing the empathy necessary to regard other creatures as fellow sentient beings — and start appreciating them for who they really are.

Maddalena Bearzi is president and co-founder of Ocean Conservation Society. Her latest book is “Stranded: Finding Nature in Uncertain Times.” She lives in Los Angeles.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.