- Share via

LAHAINA, Hawaii — Archie Kalepa has spent his life in the ocean. He’s a legendary surfer and world-renowned pioneer of techniques to rescue people when colossal waves crash down on their heads.

So his first glimpse of his still-smoldering hometown was, of course, from the sea.

Roads into Lahaina were closed when Kalepa flew into Maui two days after a wildfire had leveled much of the historic town of 13,000. But a network of friends spirited him onto a boat and raced him up the coast.

As the boat came to shore and everyone on board took in the blackened hillside, the melted cars, the teetering columns of ash that used to be homes, they started to cry, Kalepa said. Sitting in the back, with the stuff of nightmares fast approaching on the horizon, Kalepa swore to himself he wouldn’t break down.

“Be strong, be strong, be strong,” he whispered.

He knew he was about to wade into the arms of friends and family and neighbors who were “lost in the reality of what happened to them, not knowing what to do or where to begin,” Kalepa said.

They would need someone to rally around.

Less than a week later, Kalepa’s frontyard has been transformed into a supply depot to rival those established by the government and aid organizations. Life-sustaining staples — water bottles, gas cans, tents and food — are stacked neatly, and everywhere.

The stuff is free to anyone who stops by, especially people from the neighborhood, which sits on land where, by law, you have to be at least 50% native Hawaiian to buy a house.

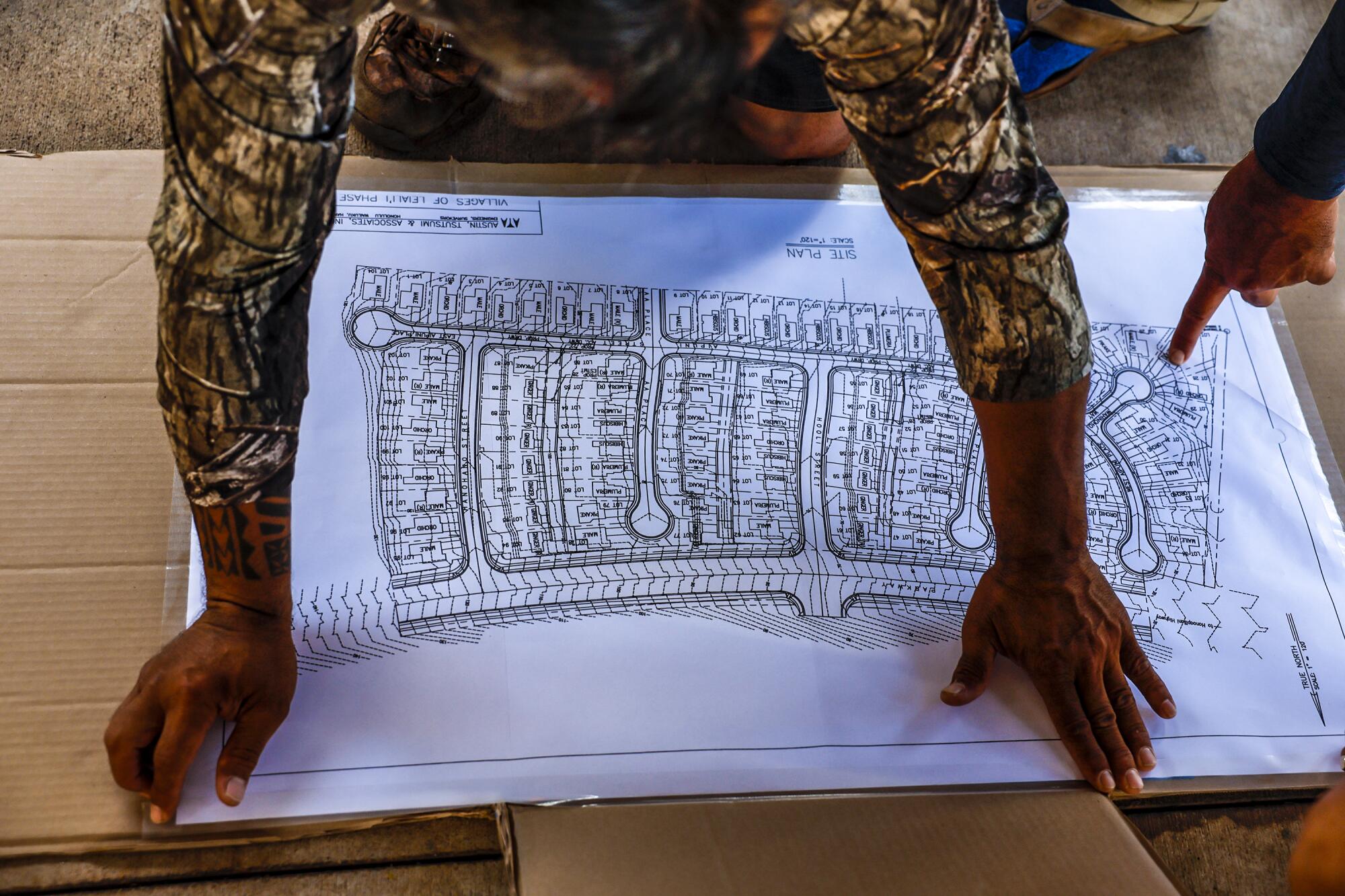

While public officials come under scrutiny for their failure to prepare for this disaster and a faltering response to what’s become the nation’s deadliest wildfire in the last century, close-knit networks of Indigenous Hawaiians, like Kalepa’s, are mounting efforts to ferry supplies and people with needed expertise past the government roadblocks into their neighborhoods.

The Lahaina fire in West Maui ignited as firefighters focused on the Upcountry fire. What happened next — the deadliest U.S. wildfire in more than a century — left the historic town in ashes.

They include doctors, nurses, chefs, firefighters and in some cases journalists invited in to tell the story.

Once past the primary roadblock just south of the seaside town, the journey to Lahaina winds about 15 miles up the coast, with the West Maui mountains rising to the right and the impossibly blue Pacific Ocean on the left.

There’s almost no sign of the ravages of wildfire until you’re within sight of the town — its center torched into rubble and ash — and acrid fumes burn your eyes and lungs.

The way to Kalepa’s neighborhood leads past the decimated downtown, where a second layer of official security personnel have set up blockades to keep gawkers from taking gory photos for social media or tramping through ash that could contain unidentified human remains.

Kalepa’s neighborhood, just north of the town center, is one of the few places in Lahaina where a majority of the houses remain standing. That’s thanks to luck and the ferocious efforts of residents and firefighters to “hold the line,” Kalepa said.

But not every home could be saved. The house behind Kalepa’s, just a few paces away, is burned almost to the studs.

As people flooded a main road out of West Maui, the inferno caught up. A resident who managed to escape with his family says he will never forget what he saw.

Unloading the stream of trucks rolling into Kalepa’s cul-de-sac — conventionally suburban except for the breathtaking ocean views — was an informal battalion of fit, bronzed bodies: surfers from Argentina, off-duty firefighters from other parts of Hawaii, even a contingent of U.S. Navy SEALs.

They weren’t officially deployed, one of the SEALs told a reporter, but they had trained under Kalepa in ocean survival and he’d made a lasting impression. So when they heard he needed help, they just came.

Kalepa, 60, gained early fame as a pioneer of tow-in surfing, using a jet ski to gather enough speed to catch the towering, terrifying, 70-foot waves that slam into the north shore of Maui at the surf break known as Jaws.

But that was for fun.

Kalepa made his living as a lifeguard. Before he retired, he spent 30 years as a member and eventual leader of Maui County’s ocean rescue service. His biggest contribution to the surfing world has been saving others. He’s credited with helping to develop the technique of attaching a floating sled to the back of a jet ski to race in and rescue surfers from the sometimes fatal consequences of wiping out in roiling whitewater when those giant waves collapse.

Watch any video of big-wave surfers today, anywhere in the world, and you’ll probably see the jet skis circling.

Today, Kalepa travels the world training people in water rescue.

He was working in Lake Tahoe when the fire consumed Lahaina. He woke up at 4 in the morning with an odd sense of dread, he said, and started seeing all the posts on social media. A relative called to report that his house was gone — not accurate, thankfully.

“But I was just shaking,” Kalepa said.

Before he got back to Lahaina, he started calling friends, telling them he was going to need bottled water, gas cans and tents. The distance worked in his favor, because electricity and the internet were out in the town and communication from there was almost impossible.

1

2

3

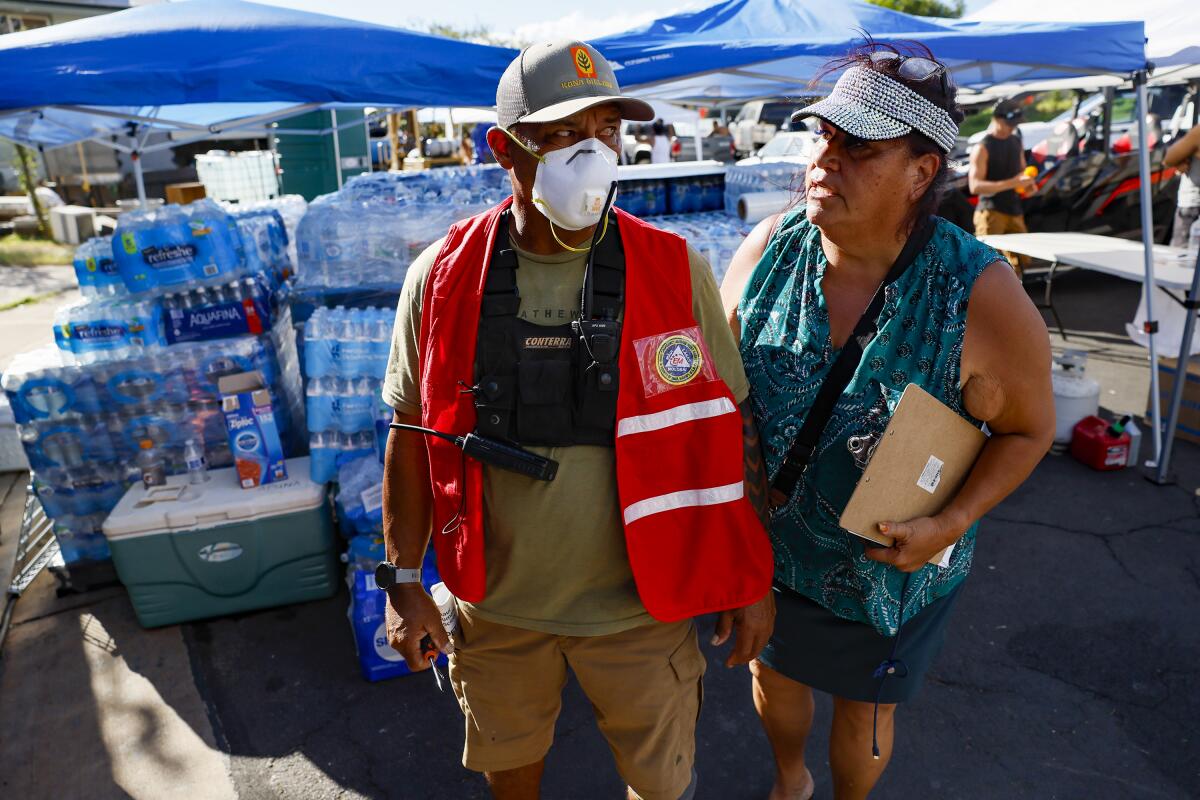

1. Volunteers greet Hawaii federal firefighters. 2. Archie Kalepa and Melissah Shishido gather supplies for Lahaina residents. 3. Supplies for Lahaina fire victims are gathered and delivered by Hawaiians sailing on a large catamaran. (Robert Gauthier/Los Angeles Times)

When he finally got home, Kalepa cleared his frontyard, waited and hoped. Within 24 hours, the critical supplies he asked for started showing up. The flow hasn’t stopped since.

Na‘alehu Anthony, a friend with an ocean-going catamaran used to retrace the routes of ancient Hawaiian sailors, pulled the Starlink satellite internet receiver off the boat and raced to Kalepa’s house. Less than an hour after he arrived, Kalepa and his growing crew of volunteers were back online and organizing donations, Anthony said.

Melissah Shishido, 60, a friend and fifth-grade teacher, emerged as field marshal for the operation. With her clipboard, two cellphones, walkie-talkie and a sparkling visor that looks a lot like a crown, Mish, as she’s known, seemed firmly in charge of logistics.

During a stop at Costco to pick up supplies — Kalepa was hosting dinner in his yard for dozens of weary firefighters who had spent the day combing debris — Mish pulled a handful of credit cards from her purse. They had been donated by friends, family and acquaintances. She looked like a Las Vegas card dealer rifling through them for one with enough money left to cover the $555 bill.

“It’s a nightmare keeping track,” she said.

Outside, as she waited for another friend to arrive with a truck big enough to carry the load, she confided she was running on “fumes.” She said she’s not a fan of the government agencies and aid organizations that can be lumbering and tentative when it comes to getting things done.

“We just gotta do what we gotta do,” she said, her phone ringing. “We don’t have time to wait for anyone else to come in to help.”

Among the things Kalepa tells the people he trains to survive an ocean disaster is to stop and think. “When you’re surrounded by danger and you’re feeling all of this fear, the only way you can survive is talking yourself out of it,” he says. Focusing on what’s immediately in front of you, and solving problems one at a time, staves off panic and gets you closer to safety.

“It creates a sense of calm,” he said, even in the worst moments. “It creates a sense of what you need to do.”

That’s essentially what he’s preaching now.

With the initial phase of the Lahaina disaster winding down — the people who can be saved have been — Kalepa is looking ahead to what’s next. Although he’s awash in supplies now, he worries what will happen when the fire drops off the public’s radar.

“The world that we live in today is energized by social media,” Kalepa said. “When you no longer are the hot topic, people aren’t paying attention.”

The cost of living in Hawaii is already higher than in any other state in the country. Many of his neighbors, particularly those who work in the tourist industry, hold down multiple jobs and still are barely hanging on. And that was before the fire destroyed everything.

One thing that kept a lot of them rooted to their ancestral soil, and out of the steady stream of Hawaiians leaving for places like Las Vegas where land is cheap, was the house they owned in neighborhoods like Kalepa’s. Now, with so many of those homes incinerated, there’s a gnawing fear, born from years of injustice, that wealthy land-grabbers will somehow find a way to buy the scorched earth and displace the natives forever.

“We need to stay strong for the long haul,” Kalepa said. “So everybody who owns a home here can return.”

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.