From the Black Death to AIDS, pandemics have shaped human history. Coronavirus will too

- Share via

Hernan Cortés fled the Aztec capital Tenochtitlán in 1520 under blistering military assault, losing the bulk of his troops on his escape to the coast.

But the Spanish conquistador unknowingly left behind a weapon far more devastating than guns and swords: smallpox.

When he returned to retake the city, it was reeling amid an epidemic that would level the Aztec population, destroy its power structure and lead to an empire’s brutal defeat — initiating a centuries-long annihilation of native societies from Tierra del Fuego to the Bering Strait.

From the Plague of Justinian and the Black Death to polio and AIDS, pandemics have violently reshaped civilization since humans first settled into towns thousands of years ago. While the outbreaks wrought their death tolls and grief, they also prompted massive transformations — in medicine, technology, government, education, religion, arts, social hierarchy, sanitation. Before the cholera epidemics of the 19th century, cities thought nothing of mingling their sewage and water supply.

No one can know exactly how the COVID-19 pandemic will ultimately change the world. Unforeseen consequences will lead to even more unforeseen consequences.

But stress cracks are already showing. Nations are turning inward. Rulers are seeking more authoritarian power. The decline of American leadership is accelerating. Economies are facing recessions. People are living in fear and distrust, with many losing jobs and potentially facing poverty they’ve never experienced before.

At the same time, scientists, technocrats and businesses are working feverishly to stem this pandemic and better prepare for the next one. There is little doubt that new technology will rise from this epic crisis.

So too might things less tangible.

Americans, by and large, appear to be looking to science to save the day, not to political spin and partisanship. The virus could revive faith in the inarguable forces of biochemistry, deep in the fact-based universe.

On another level, the abrupt disruption of routines that were so long considered by many unalterable — the long daily commute, the business meeting that requires a flight or two, the need to schedule children’s every hour, the go-go-go mentality — opens the possibility of a behavioral reset, for those who can afford it. Millions have stumbled onto the ancient simplicity of an afternoon walk, and many wonder if there might be a way to reduce some of the noise in their lives, keep the freeways a bit more open and the air a bit more clear.

“People tend to need a big shock to change their behavior,” said Marlon G. Boarnet, professor and chair of USC’s department of urban planning and spatial analysis.

In particular, he sees opportunities to fight a slower-moving, potentially far more destructive global disaster: climate change.

“Now we see our day-to-day habits can change more quickly than we thought,” he said. “People have had the opportunity to telecommute. The reality is they didn’t have to go to every conference. And we’re getting a glimpse of what Los Angeles could look like if we could get ahead of our transportation problem.”

He said public officials need to craft policies to make some of the positive changes permanent before old habits return and solidify.

Although many people cannot do their jobs online, those who can should consider it, he says.

“If we had everybody telecommute a day a week, you would have an incredible air quality improvement.”

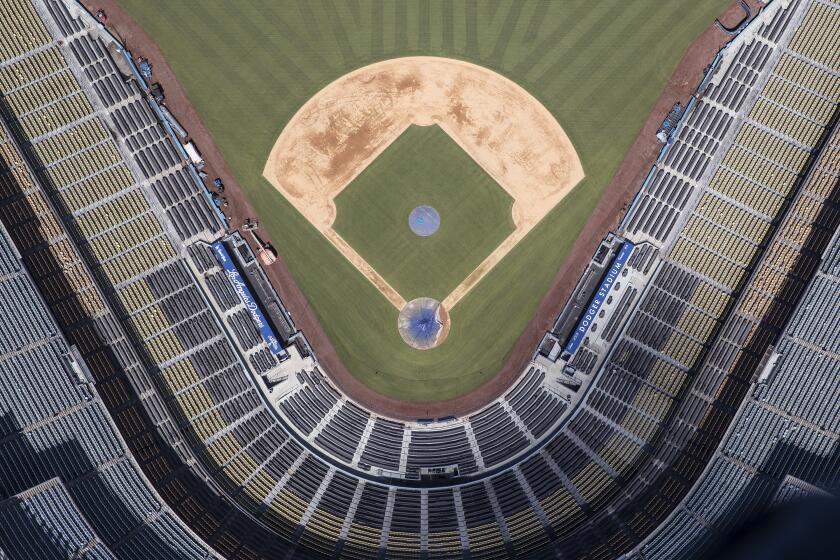

Gov. Newsom has issued a stay-at-home order and all nonessential businesses are closed due to the coronavirus outbreak. So what does it look like outside — from above?

Pandemics are famously idiosyncratic in the havoc they cause and the human adaptations that emerge in their wake. An adage among those who study these global infections: “If you’ve seen one pandemic, you’ve seen one pandemic.”

Together, pandemics and epidemics have led to advances in public health that allowed cities and civilizations to grow and prosper: germ theory, urban sanitation, vaccination, penicillin, better hygiene, isolation wards and the scientific method, which brought rationality to modern medicine.

Nations and societies rose and fell on the backs of pandemics. The Black Death of bubonic plague that erupted in the 1300s, killing half the population of Europe, dealt the final blows to the feudal order of serfdom, with waves of deadly outbreaks to follow for centuries, shaking faith in the Roman Catholic Church, and some historians suggest, making possible the Renaissance and the Reformation.

But disruptions caused by smaller epidemics, even mere footnotes in history, have also had colossal consequences. Consider how the United States obtained the vast midsection of the country that allowed it to expand westward to California and become the most prosperous nation on Earth.

In 1802, Napoleon sent the world’s greatest army to the Caribbean to put down a slave rebellion and restore French rule in what had been France’s most profitable colony, St. Domingue. But an epidemic of yellow fever devastated his troops, killing an estimated 50,000 and forcing his army to leave in defeat.

Without the wealthy island colony to fund his grand plans on the American continent, Napoleon retrenched to Europe to face off with England. St. Domingue became Haiti, the first free black republic in the world, and American President Thomas Jefferson bought 828,000 square miles of French territory on the cheap, stretching from New Orleans to the Rocky Mountains to Canada.

So in the great cascade of human events, Kansas City and Denver, and by extension Los Angeles and Seattle and the Silicon Valley, owe a bit of themselves to that long lost ancestor, a pestilence in the Antilles.

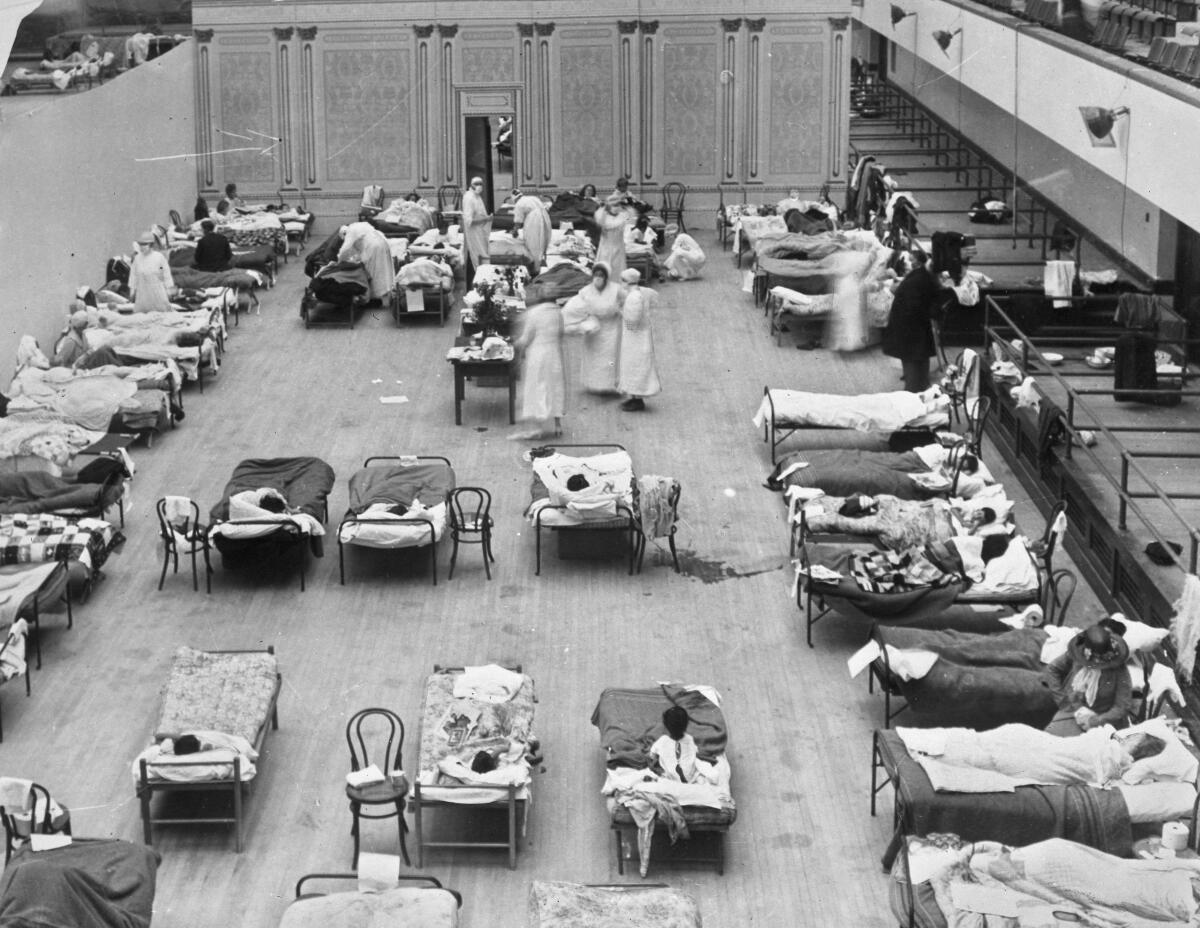

Yet a much bigger biological disaster, the influenza pandemic of 1918, which killed anywhere from 20 million to 50 million people globally at the end of World War I, left mere ripples in terms of broader societal change. Some historians dubbed it the “forgotten pandemic,” and even the great generation of American writers who lived through it — Hemingway, Faulkner, Fitzgerald — ignored or barely mentioned it in their works.

“Nothing else — no infection, no war, no famine — has ever killed so many in as short a period. And yet it has never inspired awe, not in 1918 and not since,” wrote Alfred W. Crosby in “America’s Forgotten Pandemic.”

Disruptive events like the COVID-19 outbreak can end political inertia and result in bold changes

How the novel coronavirus — SARS-CoV-2 — will bend that human torrent is impossible to know. We’re still crashing down the first rapid.

With modern medicine, and the current data on the virus, no one is predicting the next Spanish flu or Black Death. But plenty see trouble beyond the death toll and economic fallout.

Many political scientists fear that America’s deep polarization and divisive president will prevent the nation from rallying around any big policies to save millions from poverty in the event of a recession or to massively reform our healthcare system.

No new New Deal seems likely, despite efforts on the left to pass a Green New Deal. And as the U.S. lets go of the leadership role it has wielded since World War II and nationalism bubbles up across the planet, it will be harder for countries to cooperate on the big transnational crises: climate change, cybersecurity, terrorism, nuclear weapons proliferation, refugees, every sort of trafficking and the next pandemic. Countries might turn inward, supply chains contract, the global economy sputter.

“This is the most global crisis of our lifetimes,” says Ian Bremmer, a political scientist and founder of Eurasia Group, a political-risk research and consulting firm. “We desperately need a coordinated response.

“If you look at the last couple of crises we had, whether it’s 9/11 or the Great Recession, it was a U.S.-led-global order,” he says. “There was a rally-round-the-flag effect. There was a strong cohesiveness between the U.S. and our key allies around the world.”

George W. Bush had a 92% approval rating after the 9/11 attack.

“Trump is at 46,” he says.

Bremmer calls this pandemic the first “G-Zero” crisis, without the Group of 7 or Group of 8 industrialized countries to provide global leadership.

“No one is going to replace the United States, but China is certainly going to take advantage of the geopolitical vacuum that’s being left by the U.S. right now, and it’s going to cause a lot of American allies to hedge more.”

But taking a less internationalist role could have some advantages too, Bremmer says. He notes when the Cold War ended, there was much talk of a “peace dividend,” in which the U.S. would scale down its defense budget and focus on building infrastructure and education. But President Clinton was stymied by resistance from the defense industry and opponents in Congress, and then 9/11 led to costly wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the global war on terror.

Bremmer hopes to see an effort like that, but fears the economy might be crippled in the short run.

“The U.S. government hasn’t been adequately investing in its citizens for decades,” Bremmer said. “It’s not going to be easy. But it’s now or never.”

Health policy experts hope that, at the very least, the pandemic leads to the buildup of state and local public health agencies, led by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, to meet the next new contagion and better deal with other behavioral health challenges that affect large swaths of society, including obesity, smoking, vaping, sexually transmitted diseases and the opioid epidemic.

“Our less-than-halting response to this shows we need a real public health system in this country,” said Drew Altman, president and chief executive of the Kaiser Family Foundation. “A system that is able to rapidly test whether we have a pandemic, and trace and isolate cases.”

Altman does not see this pandemic changing the political equation on a nationalized healthcare system. “Theoretically, this is a short-term crisis,” he said. “At some point Republicans and Democrats will return to form.”

Charlie Cook, who has tracked campaigns and trends for three decades for his nonpartisan political guide, says Americans don’t see this so much as a failure of the medical system but “more of a civil defense/homeland security threat to the nation.”

And he doesn’t think the chaotic federal response is convincing many people that it should be in charge of their healthcare. What many hope for is a return to faith in science, expertise and hard truths.

“I can imagine that the anti-vaccine movement will finally go into decline,” said Daniel Hallin, a UC San Diego communications professor who has studied how information spreads during epidemics. “Possibly a shift toward appreciation of why we need competent government.”

He expects that people will be more cognizant of washing their hands and touching things for a flu season or two, but that when the virus fades from memory they will return to hugging and shaking hands, going to concerts and movies and restaurants. “When people say this will change the world as we know it, I don’t see that.”

But Larry Diamond, a political scientist and senior fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, has a different vantage.

“I think this is going to be a very long, protracted crisis,” he said. “I think it’s going to be very deep and multidimensional. I think the effects are going to unfold over many years.”

Diamond, who has spent four decades promoting democracy in more than 70 countries, is particularly concerned about authoritarians exploiting the crisis. Surveillance used to track people exposed to the virus can be turned against political enemies and dissidents. Critical information can be suppressed, as was the early outbreak in Wuhan, China, allowing the virus to spread across the world.

“The Hungarian parliament has just passed a law giving the authoritarian prime minister absolute unchecked decree power,” he said. “I think were going to see more and more efforts to use the crisis to suppress freedom of information and civil liberties and judicial independence and legislative and other institutional checks and balances.”

And he doesn’t fear this happening only in foreign countries. He is dismayed that Congress is not rallying behind a bill to make sure every voter in America can cast their ballots by mail in November, when epidemiologists say the Northern Hemisphere could be in the midst of another outbreak.

“We just cannot allow a situation where an incumbent president comes back in late October and says the election has to be postponed because we have a resurging public health crisis,” he said. “We’ve got plenty of time to make this transition. Our democracy is at very great risk if we don’t do so.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.