- Share via

For decades, this nonprofit has been at the helm of a process that can mean life or death for many Southern Californians: the recovery of kidneys, livers and other organs from deceased donors for transplants.

And for years, federal regulators have deemed OneLegacy to be falling so far short that it could eventually be shut down.

Their verdict comes from a measurement system rolled out in recent years that found the nonprofit has been recovering organs from possible donors at lower rates than the majority of such organizations across the country, according to the latest report released by federal regulators.

OneLegacy has repeatedly ranked among the lowest performers based on its “donation rate,” one of two metrics used by the federal government to gauge how effective organ procurement organizations are at their lifesaving work.

Critics including Rep. Katie Porter (D-Irvine) have excoriated many such organizations for “shocking mismanagement,” saying that it has resulted in fewer donated organs making it to patients. Porter said OneLegacy in particular “has failed families of organ donors and recipients alike for over a decade.”

If OneLegacy continues to lag in the government metrics, it could lose its longtime position managing organ procurement across seven counties in Southern California. In 2026, federal regulators are slated to begin doing something they have never done before: stripping the lowest performing agencies of their duties and offering other contractors a chance to take over their regions.

The federal plan to crack down on underperformers has been rolled out amid sharp concerns in Congress about the power that each of the 56 nonprofit agencies holds over organ donation in its region — a system denounced as an “unchecked regional monopoly” in one report repeatedly cited by lawmakers.

Dozens of people on the organ waitlist die or become too sick to receive a transplant every day, and “that’s not just an unfortunate or sad or heartbreaking inevitability,” said Jennifer Erickson, a Federation of American Scientists senior fellow who worked on organ donation issues in the White House under President Obama. “That is a result of the government’s own contractors not doing their job.”

OneLegacy has argued that the federal metrics rely on insufficiently reliable data about deaths and fail to account for demographic differences that could skew the results against agencies that serve more people of color.

The Southern California organization says it is performing well, based on its own analysis of donation data. Last year, it opened its second facility where people can be transported for organ and tissue procurement, which Chief Executive Prasad Garimella credited with maximizing the number of organs recovered from each donor, compared to doing the same work at hospitals juggling other patient needs.

“The most important thing that we’ve done is assure that the management has all the tools and resources they need to go after every single possible organ and donor that they can,” said Dr. J. Thomas Rosenthal, a UCLA professor emeritus who sits on the OneLegacy board.

The Azusa facility has a “donor care unit” that looks like intensive care, where people who have lost brain function can be sustained on ventilators and other support equipment before being wheeled to the operating room. On a June afternoon, OneLegacy staffers lined the hallway to the operating room to honor a soon-to-be organ donor. As a recording chosen by his family of “Mas Allá Del Sol” played, a woman sobbed before finally releasing the hand of the motionless patient on the gurney.

Inside the brightly lit operating room down the hallway, a passage of Scripture chosen by the family was read aloud — “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want” — before the surgical team observed a moment of silence in their blue gowns, then made the first incision.

Three years ago, Tonya Ingram complained about failures of organ procurement organizations, naming OneLegacy as “one of the worst in the country” in an NBC News opinion piece. Ingram, a Los Angeles poet and mental health advocate, argued that a “horribly broken” system had stranded kidney patients like her on dialysis.

As a 28-year-old, “I should be busying my days with travel and thinking about my next tattoo,” Ingram wrote. “Instead, my schedule is doctors appointments and surgeries and medication and protecting my compromised immune system.”

Thomas Mone, then the chief executive of OneLegacy, reached out to Ingram in an email obtained by The Times, telling her OneLegacy had seen tremendous growth in donation and critics were “preying on the understandable fears of those afflicted with organ failure.” He urged Ingram, a Black woman, to “help people in your ethnic group in particular to choose to donate life, as the need is greatest among that community.”

Ingram died this winter at the age of 31 after years of waiting for a kidney.

OneLegacy serves Los Angeles, Orange, Kern, Riverside, San Bernardino, Santa Barbara and Ventura counties. The federal metrics indicate that in 2021, among patients in its region who died from causes broadly consistent with suitability for organ donation, the rate of those who provided an organ was 9.3 per 100 — less than half the rate of the highest performing organizations, which serve Utah and northwest Ohio. To count under the metric, a donor must have an organ used for transplant or for pancreas research.

To reach the same rates as higher performers in the U.S., OneLegacy would need to have recovered more than 400 additional organs that year, according to the federal report. “OneLegacy’s failures mean hundreds of potential organ transplants never happen,” Erickson said.

Rosenthal and others have argued that the federal metrics are faulty because they rest on death data that include people who can’t become organ donors, such as those with cancer. University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus professor Jesse Schold said the metrics are “not reliable to the extent that we want to close organ procurement organizations based on this alone.” His analysis found that more detailed data about deaths could result in different rankings.

That research was funded by foundations tied to OneLegacy and another organ procurement organization. University of Miami associate professor of medicine Dr. David Goldberg, whose work undergirded the metrics used by federal regulators, called the analysis by Schold “a problematic way to try to undercut” the government metrics. His own study found close correlation between the way federal regulators are measuring deaths and the other data set analyzed by Schold.

Whether a dying person becomes an organ donor is not just the result of whether they agreed on a form at the DMV. Donors must die in a hospital and on a ventilator, which excludes many deceased people. Some possible donors are ruled out because of cancerous organs or infectious disease.

But when hospitals alert organizations like OneLegacy about possible donors, the organizations play a crucial role in whether organs are ultimately recovered. Some have failed to pursue possibly viable donors, researchers have found: In Indiana, one effort to boost organ recovery resulted in a 29% increase in transplants in a year, driven heavily by upping procurement from older donors.

Whether organs are ultimately donated can also hinge on how promptly the organization arrives at the hospital, how workers speak with grieving families to seek authorization for people not already registered as donors, and how they work with hospital staff to manage the care of patients and ensure their organs remain viable for transplant, experts said. For instance, a 2019 audit of the New York organ procurement organization LiveOnNY, published by the nonprofit news outlet the Markup, found that hospitals did not have information about what “clinical triggers” should prompt them to alert LiveOnNY about possible candidates.

OneLegacy said it provides that crucial information and its phone number on cards that can be displayed inside nurse stations or tucked on the back of an employee badge; has tracked where its employees are to maximize efficiency in reaching hospitals; and employs critical care physicians to work with hospital staff on referrals and manage the care of potential donors.

Rosenthal said the board had urged Garimella, the CEO, to “look at every single aspect of the operation and ask the question, ‘Is it functioning in the optimum way it possibly can?’” That work is not over, Rosenthal said, but “Prasad and the team have done a spectacular job in my opinion.”

The nonprofit said that in 2021, it had approached every family of a “medically appropriate referral” to try to get authorization for donation, but many referrals from hospitals ended up being ruled out because of medical problems or sheer impossibility, such as the ailing patient recovering. Only 1,260 out of 7,850 referrals that year were deemed appropriate, according to the organization.

The Southern California nonprofit is under pressure to boost its donation rates as organ procurement is under mounting scrutiny in Washington, D.C. It is among more than a dozen such organizations facing ongoing investigations in Congress.

Porter and other lawmakers have also lambasted spending at OneLegacy, including a compensation package of roughly $1 million for its chief executive and paying its board chair $100,000 a year, according to its most recent available nonprofit filings. Rosenthal and Garimella said executive salaries were set with the help of a “third party company” and that paying board members helped ensure OneLegacy could retain qualified people.

“For the time I’m asking them to invest in this organization, I think it’s appropriate,” Garimella said. The last available nonprofit filings indicate that the board chair averaged 11 hours a week at OneLegacy and related organizations; OneLegacy said the current chair averages up to 15 hours a week.

Congressional critics have also denounced OneLegacy for arguing that its performance is tied to lower rates of donation among people of color.

OneLegacy “blames the diverse communities in L.A. for its failure to serve them,” Rep. Ayanna Pressley (D-Mass.) said at one hearing, calling it an “irrational, irresponsible and biased approach.” Failing to recover organs from Black, Latino or Asian people at the same rates as white people can put ailing patients from those same groups at a disadvantage in getting a transplant, since people are more likely to find a suitable match for an organ with someone of the same ethnicity.

Before federal regulators put the metrics into effect, OneLegacy argued that the system would unfairly punish organizations that served more people of color through “intentional disregard” of differing rates of organ donation by race. The National Survey of Organ Donation Attitudes and Practices found Americans strongly support organ donation, but Black and Asian Americans were somewhat less likely to say they would probably agree to donate a relative’s organs if they didn’t know their wishes before they died.

Mone, now OneLegacy’s chief external affairs officer, said that some newer immigrants “did not grow up with the practice of donation and transplant as part of their culture and community.” And for Black donors and their families, he said, mistrust of organ donation is an enduring problem. He pointed to an analysis by researchers at the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients, which warned that, under the federal metrics, some organizations might “appear better or worse than others due to underlying differences in the populations served.”

Other researchers have vigorously disputed the idea that poor performance is unavoidable in regions with higher numbers of Black, Latino and Asian potential donors and specifically argued against a push by some organ procurement organizations to adjust for race, saying it would conceal inequities.

One agency serving northern parts of California and Nevada, Donor Network West, has won praise for bolstering donation rates dramatically among people of color in a single year under a new director. Researchers have found some agencies have recovered organs from people of color at much higher rates than others: One analysis found OneLegacy fell far behind many other organizations in the percentage of Black and Asian potential donors whose organs were ultimately donated in 2019. Its rates also lagged for white people.

“There’s no reason why we should believe that there are significant deficits among a racial or ethnic group that are somehow intrinsic to that group,” said health services researcher Brianna Doby, one of the authors of that analysis. Instead, Doby argued decisions made by organ procurement organizations are crucial, including when and how they talk to families. In the past, researchers have found Black families were much less likely than white ones to be approached about donating.

Because little data is publicly released about how organ procurement organizations carry out their work, “we can’t even describe how often people of color are approached to donate their loved ones’ organs, or how much time families have with the [organ procurement organization], or whether providers are culturally competent in how they provide care,” said Dr. Raymond Lynch, director of transplantation quality and outcomes at Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, another author of the analysis with Doby.

OneLegacy said it devotes more time on site to cases involving possible donors of color, based on its own tracking of employee time, and Mone said its workforce matches the diversity of Southern California. Before approaching a family about donation, OneLegacy workers meet with hospital chaplains, nurses and other staff to learn more about the relatives, including the language they speak, so that they can assign a worker who speaks that language, its staff said.

“We hope to meet every family where they’re at,” said Daisy Colin, who oversees family support services. “We need to do it with the utmost compassion.”

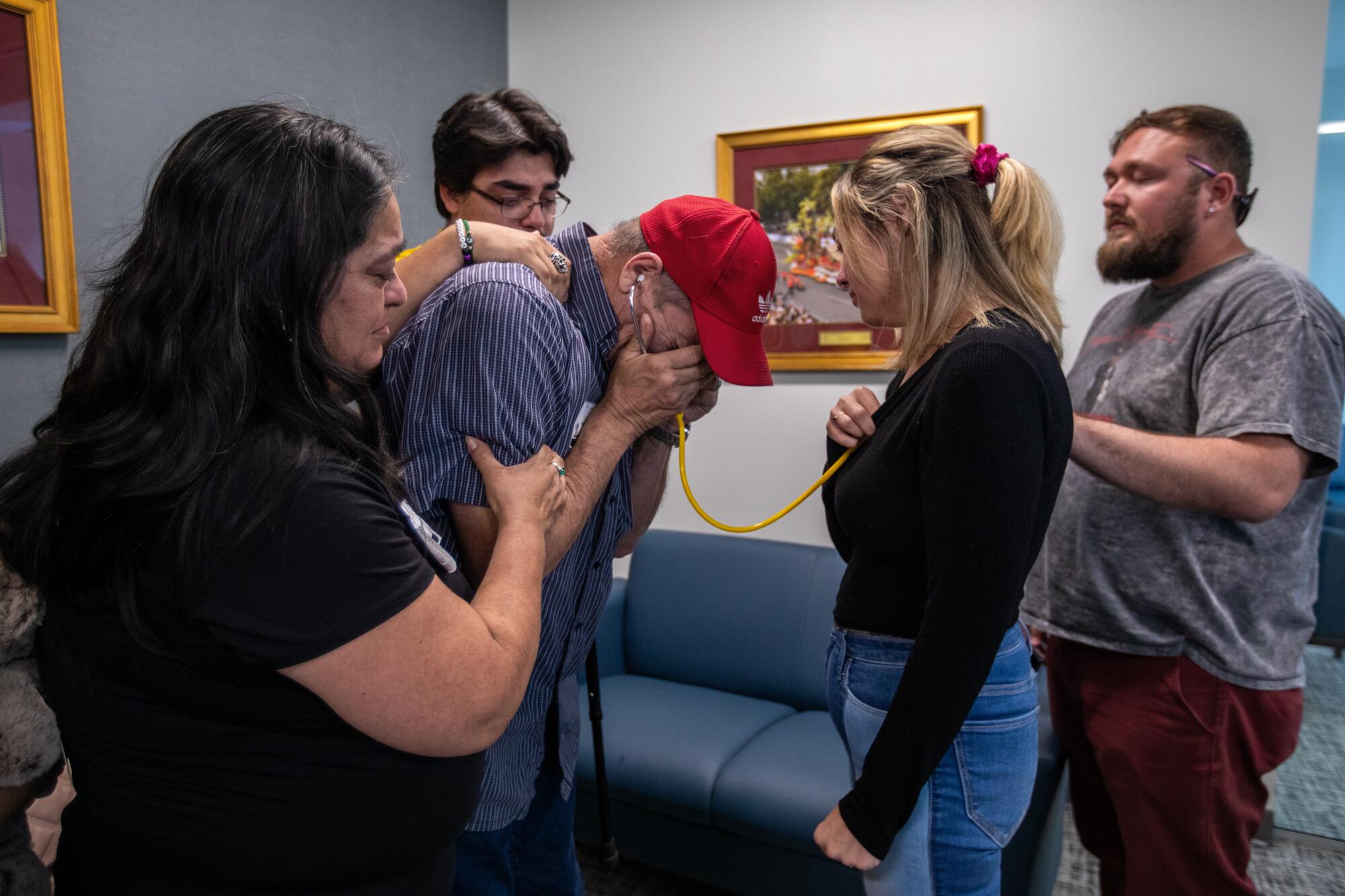

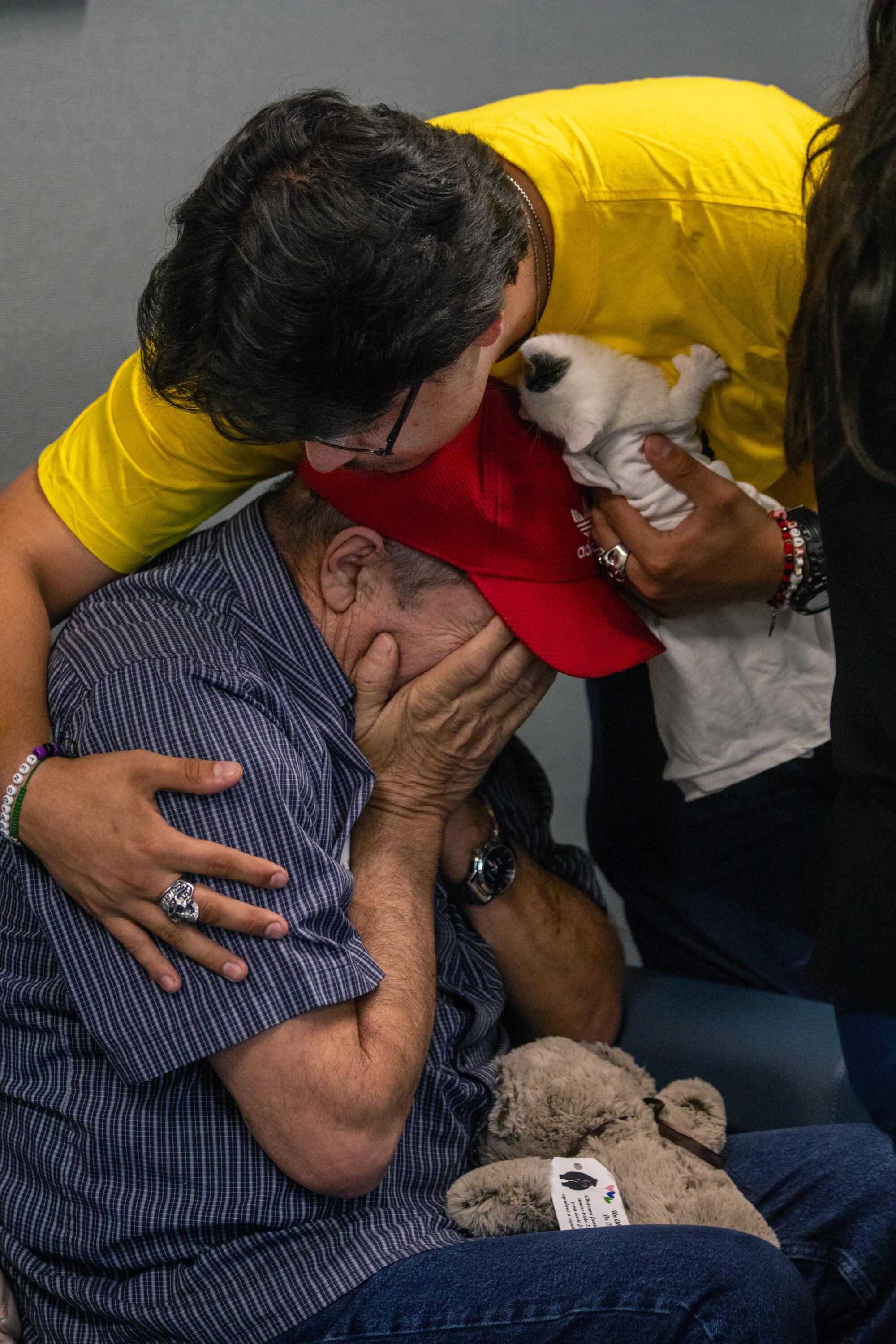

That work can be deeply personal: When Marco Garcia asked to hear the heart of his late son — now beating inside the body of a young mother — OneLegacy hosted a June meeting in a front room at its Azusa facility. Garcia listened, sobbing, through a stethoscope as family members pressed his shoulders and steadied his arm.

“I don’t have adequate enough words to say thank you,” Alyssa Sauls, who received the heart transplant, told the Garcia family.

Colin translated between Spanish and English. “He says you feel familiar,” Colin told Sauls, “and it might be because you have his son’s heart.”

Despite the federal rankings, OneLegacy stated it is performing well, citing its own analysis of donors compared to “eligible deaths.” But federal regulators have stopped relying on eligible deaths, which are reported by the organ procurement organizations themselves, deeming them “subjective.” One analysis by Kentucky researchers found “widespread variability in how they are captured” and concluded they were not a “suitable metric” for gauging performance.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in the past has stopped short of shutting down poor performers amid such objections to past metrics. The current system sets targets that are tied to how well other organ procurement organizations have performed in securing donors and transplanted organs.

In Congress, Porter has questioned why OneLegacy is performing more poorly than the organization serving San Diego and Imperial counties, which has “similar patient demographics.” Mone, asked about the gap, mentioned a higher percentage of white people in the San Diego area as one factor.

But a Times analysis found that among white people who died of coronary heart disease and other causes generally consistent with organ donation — the same ones included under the federal metric — OneLegacy had lower rates of donors than the San Diego agency from 2018 through 2021. OneLegacy also had lower rates among Black, Latino and Asian patients than the San Diego-area organization in almost every year, the Times analysis found.

OneLegacy argued that the San Diego area also differs in other important ways, including higher rates of people registering to be organ donors and receiving the bulk of its donations from a much smaller number of hospitals. Lisa Stocks, its vice president of transplant services and performance improvement, formerly served as executive director of the San Diego nonprofit and said OneLegacy was taking the same steps as the highly ranked organization in San Diego.

The federal rankings come out more than a year after the donations that are measured, which means 2024 will be the year that organ procurement organizations are judged on in 2026, when the lowest performers — designated as Tier 3 — could lose authorization for organ procurement in their areas. Under the latest data, 42% of the groups ranked in that bottom tier, which includes organizations with donation or transplant rates below median levels.

OneLegacy has been in Tier 3 in each of the three years for which the data has been released — 2019, 2020 and 2021. Garimella said he is nonetheless confident that the nonprofit will not be in jeopardy in three years due to longstanding efforts to improve.

His focus, Garimella said, “is ensuring this organization continues to succeed in doing what we’ve been set out to do.”

Times staff writer Melody Petersen contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.