Column: A new era at California Endowment as longtime leader Robert K. Ross retires

- Share via

The fourth-floor office of California Endowment CEO Robert K. Ross offers an Instagram-worthy view of Union Station, Olvera Street, City Hall and Chinatown. But I found a far more interesting landscape Friday inside his corner suite.

Moving boxes. Paintings and photos bundled up in bubble wrap. Handwritten notes on file cabinets with instructions to staffers on what to keep and what to toss. Awards — dozens of them.

“In a week, man, this will all be gone, brother,” Ross said with a laugh as we sat at a small table, the one place not too cluttered with 24 years of memories. “The county and city proclamations and certificates of appreciation — I mean, I don’t want to sound ungrateful, but where am I going to put them? These things are huge. They take a lot of space, you know, and I don’t want a study that’s like a monument to s— I did, right?”

Ross, 69, a pediatrician by training, is retiring next week after nearly a quarter-century heading one of the most important philanthropic forces in California. Its financials are huge enough — it sits on $4.3 billion in assets and gave $381 million last year to more than 700 groups in the name of combating the state’s health inequities. But Ross’ legacy rests on how he helped to transform charitable giving during his tenure.

Robert Ross, 86, the president and chief executive of the Muscular Dystrophy Assn. who recruited Jerry Lewis for the organization’s annual Labor Day telethon, died Monday of pneumonia at a Tucson hospital.

Miguel Santana, head of another L.A.-based philanthropic giant, the California Community Foundation, called Ross a “revolutionary” figure who challenged his peers “to believe that the billions we steward belong to the people” and “trust in those most proximate to the issues and injustice.” Santana was referring to place-based funding — the idea that communities, not rich organizations or individuals, know best what they need and how to use grants and donations to attain their goals.

Ross and the endowment didn’t invent that movement. But their institutional weight made it de rigueur in Southern California philanthropy. Hundreds of community groups are witness to this vision. Meanwhile, the L.A. political landscape has been transformed by a new generation of elected officials trained in the nonprofit sector — including Mayor Karen Bass and incoming City Council President Marqueece Harris-Dawson, both former heads of Community Coalition.

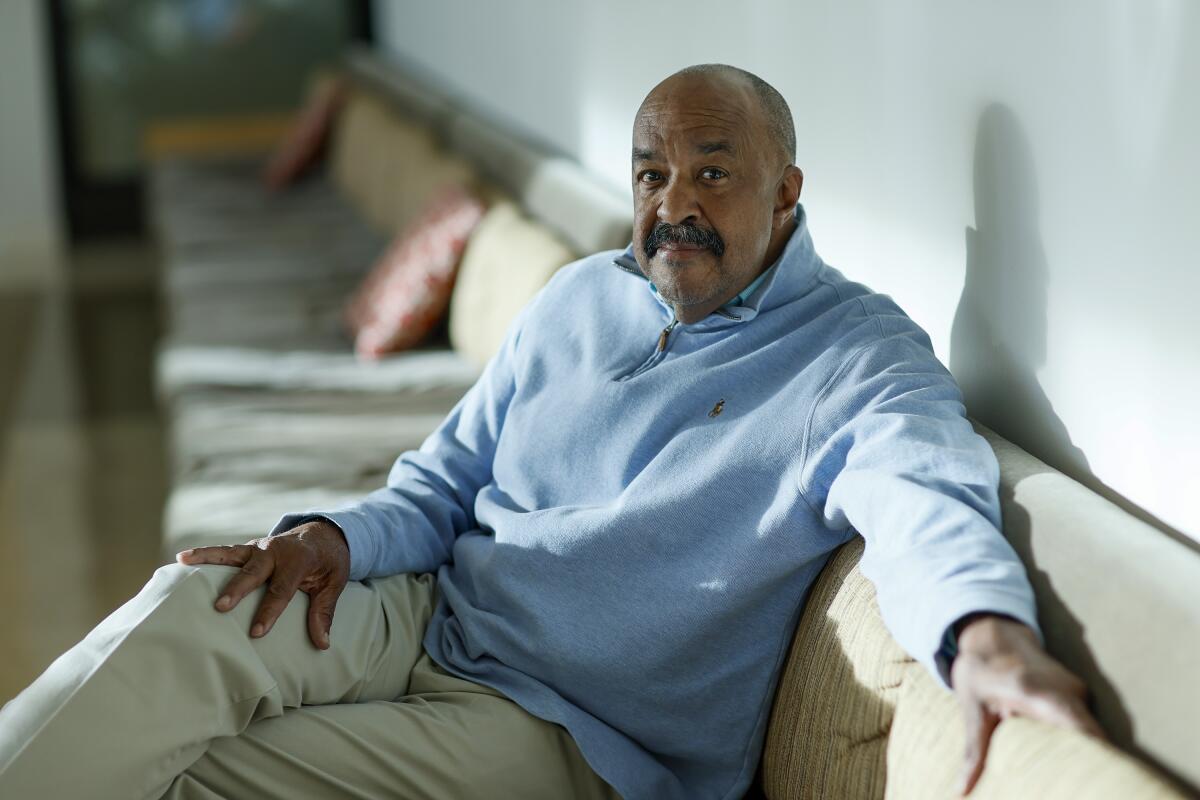

Ross cuts an imposing figure with his height, stocky build, thick mustache and perfectly Bicced head. Underneath is a gentle man with a soft voice sometimes drowned out by the symphonies and concertos of KUSC that played while we talked — “my chill music,” he said. Passionate gestures during our one-hour talk — hands clasped in gratitude or tapped on the table to make a point, eyes closed in contemplation, thoughtful silences — and a lifetime’s worth of anecdotes brought his crusading spirit to life.

“I love the work of being in this fight” of social justice, Ross said. “If you’re not fighting, it’s not social justice.”

The Bronx-born son of a Black father and Puerto Rican mother was galvanized into action while working as a pediatrician in Camden, N.J., and Philadelphia during the late 1980s, at the height of the crack epidemic. He described having to clean up vials outside the clinic every Monday. “It was lunacy,” he said. “And, you know, excuse my language, ‘What the f— is going on here?’”

Ross left the private sector to head Philadelphia’s public health department, then moved to a similar role with San Diego County in 1993.

“I knew this much about Cali,” Ross said, pinching his thumb and index finger together. “And I flew out in February for the interview. It was a dank, icy, cold, gray Philadelphia day. And when I landed in San Diego, it was like a chamber of commerce day. Like, picture perfect. Seventy-five [degrees], blue sky.”

Ross stayed there until taking the endowment position in 2000, tiring of how “you have immense resources at your disposal” in government “with very little flexibility in terms of how to deploy those.” One example he came across early in his new role was in Boyle Heights, where residents had long used the unpaved sidewalks around Evergreen Cemetery as a jogging track in the absence of publicly funded alternatives.

“It’s like, ‘How outrageous is that? The only safe place in your community is a cemetery?’” Ross remembered thinking. “People would hear that story and sort of chuckle — ‘Oh, that’s interesting,’ or, ‘That’s creative.’ It’s not. It’s a tragedy.”

He pushed the California Endowment to focus on place-based philanthropy. Out of that came Building Healthy Communities, a decadelong initiative that distributed $1 billion to groups in 14 places from Del Norte County to the Coachella Valley to San Diego.

Early on, though, Ross admits he was sometimes “well intended but arrogant.” He and his staff visited the Youth Justice Coalition, a South L.A. nonprofit that helps formerly incarcerated people. “This place was grassroots — like, old-ass building, frayed carpet, paint’s chipping away, but great energy.”

Ross told the group about the endowment’s programs to help juvenile parolees. “And this kid says to me, ‘Yo, doctor, that’s kind of nice, but, you know, really, man, we don’t think these kids need to be in lockup in the first place.’”

“I am a board-certified pediatrician, master’s in public health,” he continued, now flashing a grin. “Former head of a health department, running California Endowment. And I had to be subjected to a lecture by a 19-year-old who was formerly incarcerated who basically says, ‘We don’t need to fix youth prisons. We need to close them’? And I remember leaving that day feeling kind of humbled — but enlightened.”

California Endowment broadens ambitions and narrows scope

Building Healthy Communities is how I first heard about the endowment. Activists I knew in Orange County were intrigued but initially skeptical at staff members’ willingness to hear out ideas, no matter how radical, in an area long dismissed by L.A.-area do-gooders.

One of those O.C. activists was Carolina Sarmiento, a community studies professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who sits on the board of El Centro Cultural de México. The Santa Ana nonprofit uses music and art classes to organize residents around issues such as gentrification and cultural identity, and it also puts together one of the biggest Día de los Muertos commemorations in Southern California.

In 2014, El Centro Cultural was finally able to buy a headquarters, using an endowment grant. It continues to receive financial support from the endowment.

“There were few foundations that would allow us to do the work we do, the way we do, and the endowment allowed us to do that,” Sarmiento said. She credits Ross with “leading the conversation in philanthropy on how to gift responsibly in a way that they’re not co-opting social movements but letting community-based groups lead.”

I told Ross about El Centro Cultural, and he nodded.

“We’re a field that’s [now] less top down in its orientation. Quite frankly, less colonial and white supremacist. Where we [used] to say, ‘We have the money. It’s our money. Here’s what we need you to do. And if you beg the right way, we’ll give it to you,’ right?

I asked whether he thought he was successful during his time at the endowment.

Ross took a drink of water.

“No one’s asked me that question, because I think they assume that my career has been successful,” he said, looking around his office before cracking, “I have all these awards! Of course I’m successful!”

He took a deep breath. “I’ve been successful in modeling what a humble learner looks like as a leader … by listening.”

Another look around his office prompted a thought: “My favorite farewell gift — I wish I could show it to you because it’s really quite something to see — is a quilt.”

His staff sewed together T-shirts from more than 20 campaigns supported by the endowment — school truancy reduction, health coverage for undocumented residents, programs to help young men of color, parkland equity.

“That’s democracy in action. And so I feel good about that,” he said. “So much more work to do, obviously.”

More and more of L.A.’s institutional foundations have gotten behind the idea of trusting nonprofits to use increasing amounts of money as they see fit.

Ross isn’t sure what’s next for him, although he will remain on the Weingart Foundation board of directors to keep engaged in L.A. philanthropy. And although he recently moved to Huntington Beach — “One less Trump flag there” — Ross continues to believe that Los Angeles activism is leading the way for a better California.

“We can’t wait for D.C. to show us what the beloved community looks like,” Ross said, referring to a philosophy of inclusion and neighborly love made famous by Martin Luther King, Jr. “And what the state of belonging looks like. So that’s on us. L.A. can lead that. I can say that 20 years ago, I would have said, ‘Well, that’s probably up to the Bay Area to lead that.’”

What changed?

“Community organizers in this region have gotten terribly sophisticated about impact,” he said with pride. “Some of the organizations we support — they are crafty. And they are relentless. And they simply refuse to give up the fight. That’s the difference. It made the difference in O.C., right?”

“We’re still a work in progress,” I countered.

“Yeah, a work in progress,” Ross concluded. “But, man, compared to 20 years ago?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.