They weren’t caped crusaders, but these Angelenos fought corruption and won

- Share via

Still another summer of superhero movies is upon us.

Oh, ho hum.

Here IRL, the superheroes who were among us did their work less flamboyantly, with pen and paper and bank statements and muscular documents like subpoenas.

They didn’t wear Spandex suits, and anyway, you would not have wanted to see that; I know I wouldn’t have.

Sometimes they got attacked, even bombed, and they survived and triumphed, but not by being able to fly or breathe fire or control the insect kingdom the way those made-up superheroes do. And looking at their stories today, their legacies are that they probably did more good than harm, not that they vanquished all evil. This is Los Angeles, after all.

Over the course of eight years, 1915 to 1923, L.A. endured eight revolving-door police chiefs and four mayoral administrations. Infesting it all, mayors, City Council members, and district attorneys pocketed campaign money and even payoffs from gamblers, bootleggers and madams, as did the police. As Joe Domanick wrote in his fine history of the LAPD, “To Protect and To Serve,” their “donors” stayed in business, and official L.A. looked the other way. This saturation of vice was “so corrupting it was rotting the fabric of both the city government and the LAPD,” Domanick found. One liquor smuggler brazenly griped that he never got the $100,000 worth of police protection that he’d paid for.

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Los Angeles needed a man on a white horse, somebody to clean things up, or at least give the place a sheen of rectitude. So it hired August Vollmer. Vollmer already had a formidable reputation as a criminologist — the newspapers liked to call him “the real Sherlock Holmes of the United States” — and if the men who hired him thought of him as window dressing, Vollmer didn’t act like it.

In 1923, L.A. gave Vollmer 12 scant months as police chief to make things happen — and he did. He began the school that later became the police academy, and demanded professional training and conduct. He instituted science-based detection and modern technology. He wheedled money from the city for more cops, more police stations, more equipment, and he made nice with community organizations. Before coming to L.A., he had, as Berkeley’s police chief, put police on motorcycles and hired a Black officer.

And then, like the Lone Ranger, at the end of his year he rode off — back to Berkeley, and to other cities whose police needed his touch.

Vollmer’s reforms of a hundred years ago are the LAPD’s scaffolding to this day. Yet their biggest fail was a problem Vollmer’s reforms didn’t address — or perhaps even recognize as a problem.

The Vollmer definition of corrupt and unprofessional didn’t really extend to the institutionalized abuses that had already brutalized Los Angeles’ communities of color, and would continue to do so. Aggressive, quasi-militarized policing of poor and minority neighborhoods, in the name of law and order, was not a glitch; it was the programming itself, the abuse of authority in the name of authority.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, Chief William Parker spent 15 years as LAPD chief, and he was a martinet about discipline. In those postwar years, he hired ex-military men accustomed to following orders and doing battle with an “enemy.” It was Parker who came up with the phrase “thin blue line.”

The Parker policeman didn’t take hooker freebies, nor “tips” for selective eyesight about crimes. The Parker policeman, as modeled by the TV cops created by Parker’s friend Jack Webb, didn’t have so much as an overdue library book. The Parker policeman was not divorced; Parker’s LAPD driver and the future police chief, Daryl F. Gates, told me that his own divorce cost him points on the police civil service exam.

In the decades after the Vollmer reforms, middle-class and white L.A. applauded the LAPD for suppressing crime by whatever means required; behavior that would now be police misconduct, even criminal, was just what it took to keep order. The cop jargon then was about “DWB,” driving while Black, and “NHI” murders, no human involved, meaning minority-on-minority killings — and, in squad-car conversation from an officer who took part in the Rodney King beating, a racist joke about “Gorillas in the Mist.”

Los Angeles’ reputation for civic corruption pales in comparison with Chicago or San Francisco. But the City of Angels has a long history of sinners in public office.

The first big fissure in the Vollmer reforms came about 10 years after his brief tenure. “Sailor Joe” Shaw, the brother of Mayor Frank Shaw, was selling the answers to police civil service exams and other preferments right out of his City Hall office. Although the mayor modeled himself as a progressive, and welcomed people of color into civic life — he lived in South Central L.A. — over time, the corruption that permeated the LAPD leaked into other parts of government work, like no-bid city contracts and political donations from mobsters and madams.

Wendell L. Miller, a minister and founding president of the reform group CIVIC, summoned the citizenry to action thusly: “The decent people of Los Angeles must get together and force the agencies of the law to carry out the intent of the law.”

L.A.’s government house was so crooked that any number of reform groups flourished in the 1920s and into the 1930s. Organizations on the left and right created a critical mass for a housecleaning, and in 1938 Shaw was recalled, the nation’s first recall of a big-city mayor. The recall was one of the reforms that another of our civic caped crusaders helped to put in place (more about him later).

Then Los Angeles elected a new civic janitor-in-chief to swab out City Hall — Fletcher Bowron, a man not on a white horse but in a judge’s robes, a moderate of unchallenged integrity, acceptable to all of the elements of the reform movement.

Let’s take a moment here to zoom out, while the new Mayor Bowron starts his administration by firing the corrupt Shaw-loyalists in City Hall, up to and including the police chief.

L.A. civic government in that age was a sinkhole, but that sinkhole was different from its equivalents elsewhere to the east. Raphe Sonenshein, the executive director of the Pat Brown Institute at Cal State L.A., told me, “In the East and Midwestern urban worlds, reformers were often considered ‘goo-goos,’” a baby-fied mocking of the phrase “good government.”

It sneeringly implied they were “a bunch of dilettantes,” Sonenshein said, amateurs seeking some rainbows-and-roses ethical governance outside the hard-nosed practicalities of party-boss politics. “But in the Western and Southwestern states, where party organizations rarely took root, reform became a bigger movement led by Progressives, who made reform into real politics and government.”

This was especially the case in L.A., where progressivism sank some deep roots more than a hundred years ago, with the result that nowadays, “reform is real politics and government in Los Angeles, as many leaders and activists — from City Hall to community organizations to neighborhood councils — are pursuing their own visions of L.A. reform. That’s what makes this era in Los Angeles not just a reminder of L.A.’s history but a roadmap to today’s politics and government.”

Bowron was reelected on the eve of World War II. Two months after Pearl Harbor, he went on the radio and declared that had Abraham Lincoln been president at that moment in history, he “would make short work of rounding up the Japanese and putting them where they could do no harm,” and that meant Japan-born and U.S.-born alike, “good and bad.”

What was life like on Dec. 6, 1941, and in the years before then for one group of people for whom Pearl Harbor would drastically alter their lives — the Japanese and Japanese Americans in Los Angeles?

In 1942, that kind of talk only enhanced his standing. What got him booted from City Hall happened the late 1940s and early ’50s, during the Red Scare. Bowron — still operating in a good-government gear — snagged a huge federal grant to build public housing for thousands of poor and working-class Angelenos. The city used eminent domain to clear much of Chavez Ravine of its residents (most of them also, paradoxically, poor and working-class Angelenos) to build the Elysian Park Heights project.

Well, the city got the land and cleared off the locals, all right — but before the building began, the cry went up that this was a socialist undertaking.

“He took a lot of crap for that — people who were against it calling him a communist,” Tom Sitton told me. Sitton is a historian who’s written a half-dozen books on L.A.’s civic leadership.

Then the real estate industry jumped aboard, arguing that the gubmint should not be in the house-building business. And so, after 15 years in office, Bowron was voted out. L.A. bought the Chavez Ravine land back, cheap, from the feds, on the promise that it would go to some public purpose, and then L.A. traded it to the Brooklyn Dodgers in exchange for Wrigley Field in South L.A. And some magic beans.

(Fletcher Bowron Square near City Hall is named for him, and it’s a diss to his memory: a few dismal shops in the underground mall, and above ground, the pitiable six-story Triforium, intended to be a vividly lighted music box, but it’s never really worked properly, and if it can’t be fixed in time for the Olympics, better we throw an immense tarp over it and hang an “under construction” sign to keep the embarrassment from going global.)

Bowron had a couple of well-known crusading contemporaries. One of them was John Anson Ford, after whom the open-air amphitheater in the Cahuenga Pass is named. (How many of you thought the Ford was named for the renowned director John Ford? C’mon, you know you did.)

Ford came here in 1921, driving across country with his family. He’d been a Chicago Tribune newspaperman and an editor at, of all places, Popular Mechanics. The slimy mechanics of L.A. government soon engrossed him, and in 1927, he was on the grand jury looking into the Julian oil swindle, which picked the pockets of prominent and ordinary Angelenos alike. In 1934 he was elected to the first of his six terms as a county supervisor — often the only liberal on the board. Translation: a lot of 4 to 1 votes.

Ford’s enduring reforms in a changing L.A. County included establishing the county human relations commission, “to lessen the frictions that tend to produce deplorable incidents involving minority groups.” He crafted government programs to help poor and elderly Angelenos, and retired from the board at age 75. He lived to be 100, and earned his nickname, “Mr. Los Angeles.”

In 1937, he ran against Shaw and lost, but a year later, Shaw was recalled and Ford’s friend Bowron was mayor, taking up the reform cause.

The freeways, the smog, the people, the culture, the intellect — nothing and no one is spared when it comes to people from New York and elsewhere insulting Los Angeles.

These reforms looked both obvious and like a slam-dunk in modern L.A., but the forces were entrenched enough that someone saw fit to bomb people over them.

Clifford Clinton was the son of missionaries. He grew up in a chaotic, hunger-stricken China, and hunger was front and center in his mind. In Los Angeles, he operated Clifton’s cafeterias, where the policy and motto were “Golden Rule — Pay for what you wish, or dine free unless delighted.” Clinton was forever questing for ways to feed the world for pennies.

Ford asked Clinton to investigate the workings of the cafeteria at the county hospital, where Clinton — surprise — turned up waste and favoritism. This put him in conflict with Shaw, who had once overseen the hospital, and who sicced health inspectors on Clinton’s cafeterias.

Clinton came to serve on a grand jury that balked at digging too deeply into the Shaw administration, so Clinton hired his own investigator and made his own report exposing lucrative and unrelenting corruption virtually top to bottom in city and county government.

For this, the miffed grand jury foreman called him “Public Enemy Number One.” The taxes on his cafeterias were mysteriously hiked by nearly $7,000, and someone stink-bombed them.

Finally, in October 1937, a real bomb was set off in his Los Feliz house — damage, but no injuries. Three months later, Clinton’s investigator survived a car bombing. The crusade against Clinton was the handiwork of an LAPD captain acting on orders from the chief, who had ordered an open-ended investigation of Clinton and his fellow reformers.

The 1920s and ‘30s certainly needed civic reformers, but it didn’t have a monopoly on them.

The earliest of them was a husband-and-wife pair, John Randolph and Dora Haynes. You may have heard their names on some public service announcement, for the foundation they began nearly 120 years ago is still flourishing and giving away money to study, understand and improve the workings of this place.

The Haynes family were health refugees to Los Angeles at the turn of the last century. After his brief work at reform in his native Pennsylvania, John Haynes saw his new town and state in the stranglehold grip of the Southern Pacific Railway.

Haynes was a physician, and the personal doctor to The Times’ publisher, Harrison Gray Otis, whose retrograde politics could not have been more different from Haynes’. Twice, in the early 1900s and again in 1925, Haynes worked on reforming the city charter. In about 1903, L.A. voted itself the powers of the initiative, referendum and recall, nearly a decade before the state of California did.

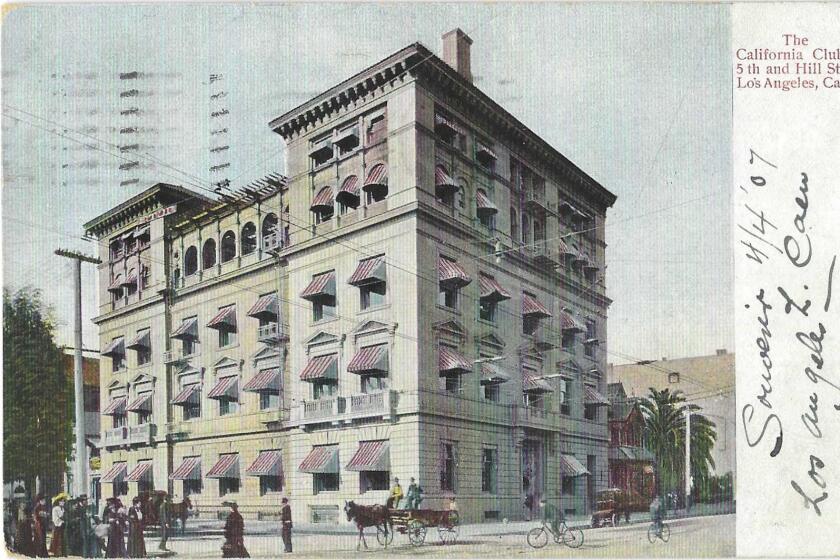

An L.A. Times exposé — and in one instance, Gloria Allred quite literally exposing sex discrimination — led the Jonathan Club, the California Club, the Friars Club and others to become less exclusive, if not less expensive.

The city’s entrenched powers did not like surrendering a morsel of power to the voting rabble. The Times hollered against it as “freak legislation … conceived in rottenness.” Needless to say, Haynes did no more doctoring at the Chandler house.

Sitton describes Haynes’ civic career in his book, “John Randolh Haynes, California Progressive.” In the city’s 1925 charter changes, Haynes helped to lock in further reforms, and he served on all manner of boards and commissions to build and monitor L.A.’s ethical guardrails, and to argue for civil service and tax reforms and public ownership of utilities.

Dora Haynes, a daughter of Pennsylvania, hit the ground running in California, working for women’s suffrage, which California women got in 1911, well before most other American women did.

Together the Hayneses crafted what is today the oldest independent general purpose foundation in L.A. — still fighting for truth, justice and something better than the old Los Angeles way.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.