‘Votes for women!’ — 110 years ago marked the first time in California

- Share via

You go, girls ... right to the voting booth.

One hundred ten years ago, California women joined their already-enfranchised sisters in five other Western states — Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, Idaho and Washington — and cast their first ballots.

It took another nine years for all American women to get the vote; the 19th Amendment made it illegal for states or the nation to stop women from voting.

It was a near thing, though, even in California.

In the Oct. 10, 1911, election, with only men voting, of course, Proposition 4 — sponsored by a Pasadena Republican state senator — passed by the skinniest of margins: 3,587 votes, which added up to about one vote per precinct across the state.

Our friends in San Francisco County — brawling, broad-minded San Francisco — voted an unequivocal “no” — just 38.1% in favor. Along with rural voters, it was Los Angeles County voters who helped Proposition 4 to reach the winners’ circle, with a countywide “yes” margin of about 5,200 votes.

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Ellen Dubois is a professor of history and gender studies at UCLA and the author of “Suffrage: Women’s Long Battle for the Vote.” And she says suffragist campaigners weren’t just the white, middle-class lot that you might have thought. For one, Dubois points out, there’s Maria Guadalupe Evangelina de Lopez, a Los Angeles native and future instructor at Dubois’ own university. She gave pro-suffrage speeches around Southern California. She had suffrage leaflets translated into Spanish and had 50,000 of them handed out by election day. At an immense rally at the L.A. plaza before election day, she delivered her speech in Spanish — a novel and compelling thing to do then.

Five months before the critical 1911 vote, Lopez threw what The Times described as a “brilliant tea party … at her home in the shades of the old San Gabriel Mission” for the College Equal Suffrage League.

According to the book “Earning Power: Women and Work in Los Angeles, 1880-1930,” she went to France in World War I, drove an ambulance, learned to fly and was honored by the French government. She died in 1977 at age 96.

Naomi Bowman Anderson, a Black woman who moved to San Francisco in the 1890s, took up the suffrage crusade but died in 1899 before it came to pass. Another formidable Bay Area Black woman, Lydia Flood Jackson, campaigned for civil rights and women’s suffrage and said feelingly that “suffrage stands out as one of the component factors of democracy; suffrage is one of the most powerful levers by which we hope to elevate our women to the highest planes of life.” She died at 101, a year before the nation’s landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act became law.

L.A.’s formidable suffrage movement still had to maneuver around restrictions on public meetings that L.A. — a famously anti-union city — had crafted to thwart labor organizing. So, as Dubois tells it, they put together a “picnic” where they handed out “votes for women” doughnuts. (I have no idea what the crullers actually looked like, but I hope they were frosted in the suffragette colors of purple, white and green.)

Katherine Edson was a pillar of the suffrage movement here; at the time, activist women of means and social standing were called by the genteel name “clubwomen,” but a lot of them, like Edson, kicked posterior. In later years she sought and got a minimum wage and better working conditions for women. But in October 1911, Dubois noted, she exhorted Los Angeles suffragists not to “lull yourself into the belief that the vote has been won;” that they should “begin early and work late” on election day. Scores of cars — this was Los Angeles, after all — rolled out onto the streets on election day to take voters to the polls.

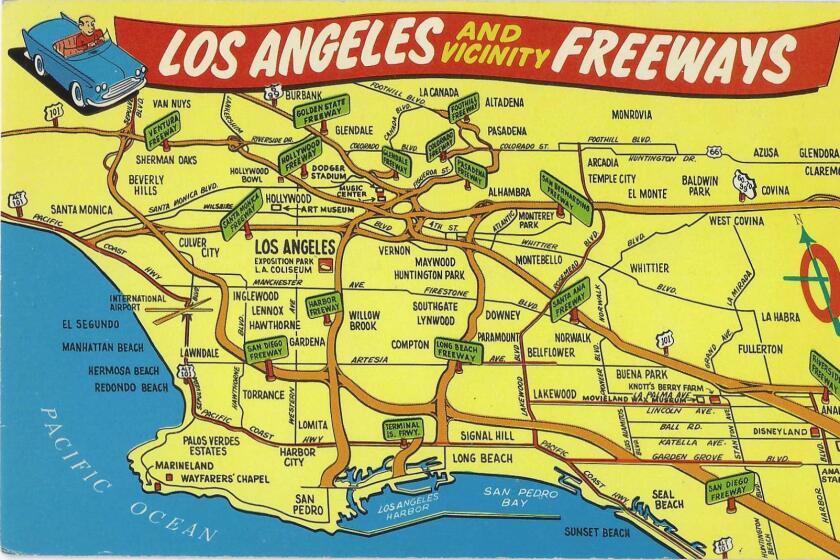

There is no Beverly Hills Freeway. Nor does the 2 connect to the 101. What even is the 90? These are the freeways that didn’t happen as planned.

The pushback to women voting was pretty muscular. In California, the Liquor Dealers League worked especially hard to keep women and their moralizing sentiments away from the polls; the temperance movement already had a good head of steam, crusading against the ruination that drunkenness was bringing to families, when a man sometimes drank up most of his weekly pay at taverns tempting him between his workplace and his home.

Tobacco and gambling interests also went weak at the knees thinking of women’s power at the polls to interfere with carousing and corruption.

But some of the opposition took on the guise of protecting the little lady from herself.

A month before the decisive October 1911 election, a prominent member of the local Men’s League Opposed to Extension of Suffrage to Women argued that “We are not fighting women. We are fighting for women, fighting lest the efforts of an overenthusiastic minority should succeed in imposing useless burdens upon the women of our state.” The speaker was a prominent San Marino man, George S. Patton, father of the World War II general. Referring to a popular operetta of the time, suffragists called the league “the Chocolate Soldier brigade.” A “chocolate soldier” was a strutting man with an overweening belief in his own fabulous importance.

The Times, I am sorry to say, was venomously opposed to women’s suffrage. Venomous was pretty much the default tone for anything the paper’s publisher, Gen. Harrison Gray Otis, didn’t happen to like. But this venom was flavored with snark, something between “don’t worry your pretty little head about it” and “there’s probably nothing in your pretty little head anyway.” To The Times, Proposition 4 was a “pet proviso.” The cause sent “charming young women” to lobby men with their coquetry.

Instead, it offered this: “The Times honors the women of Los Angeles more than those who are trying to lure them from the mellow radiance of the home into the fierce glare of publicity. It would regret to see our maidens acting as members of caucuses and our wives leaving the babe to wait in the cradle while they crowded to the polling booth.”

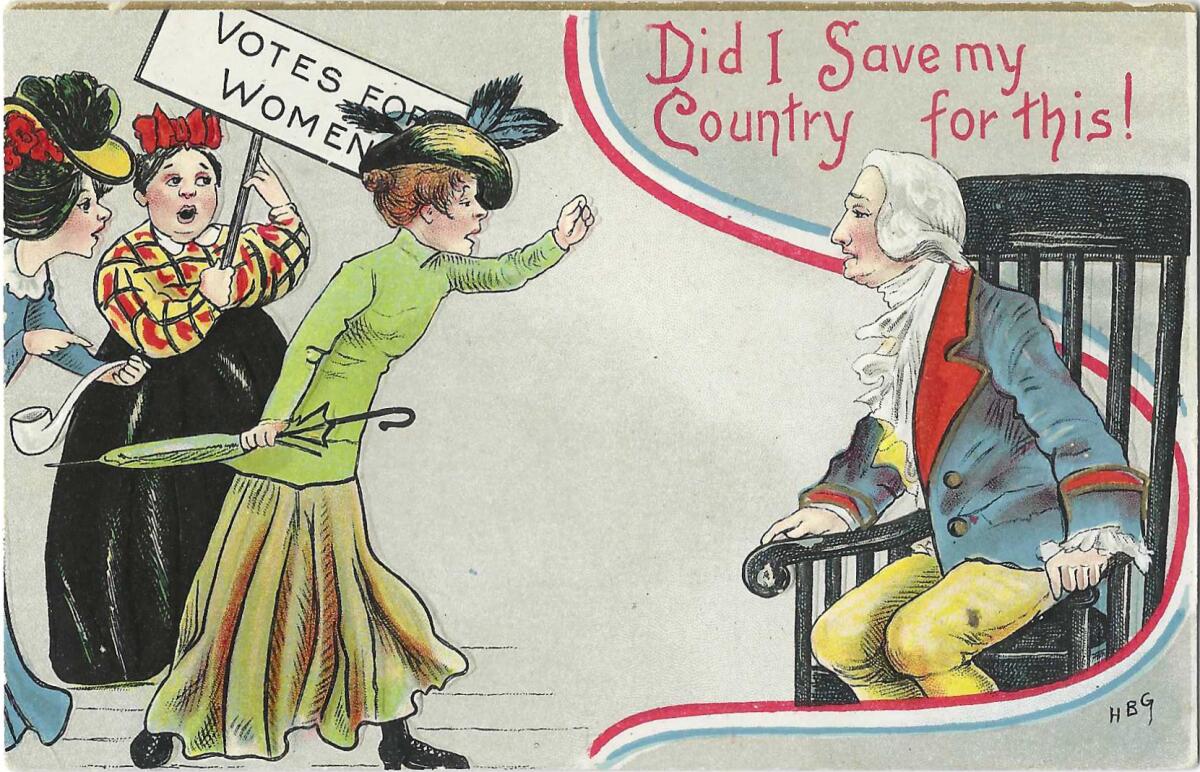

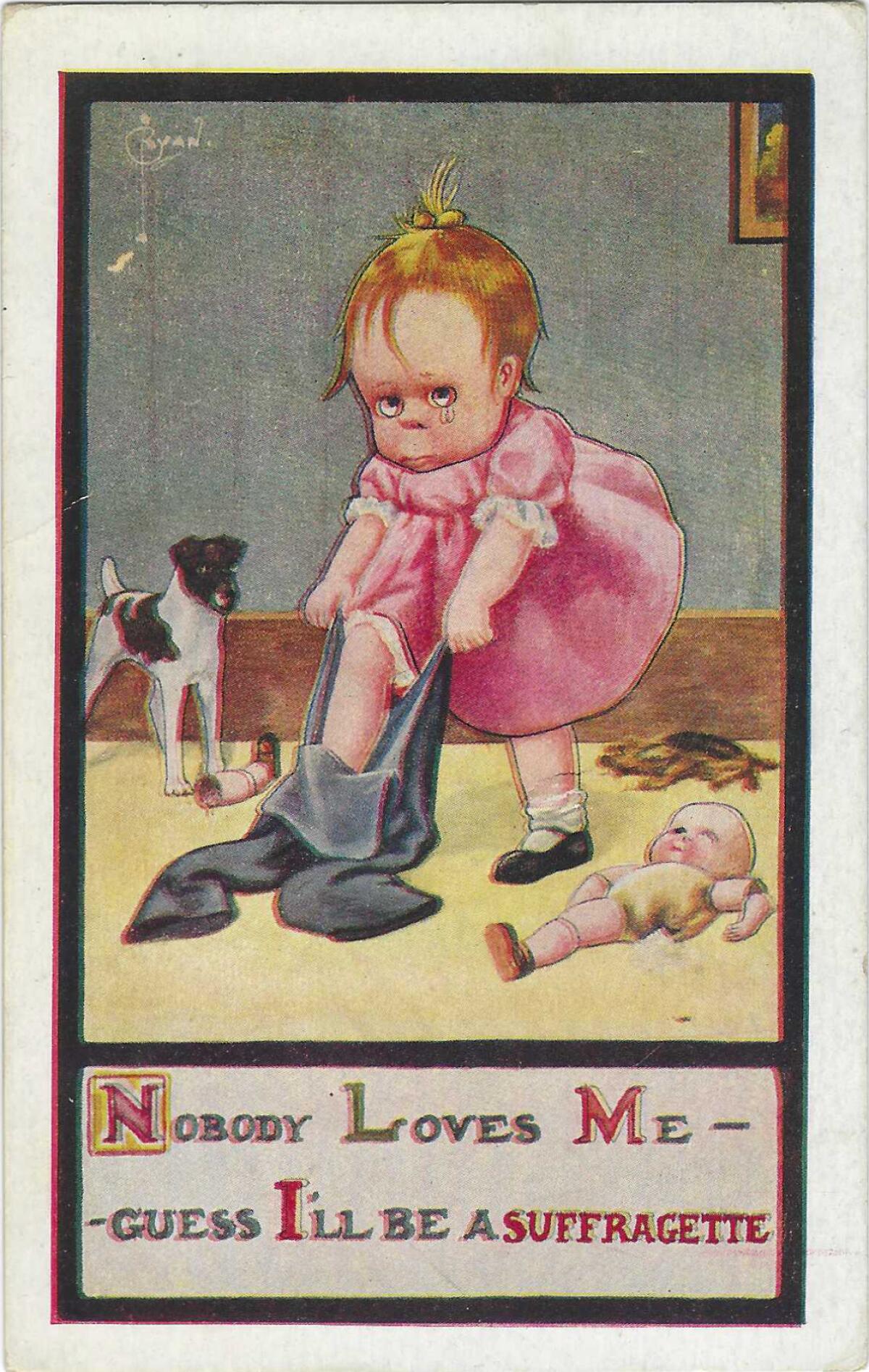

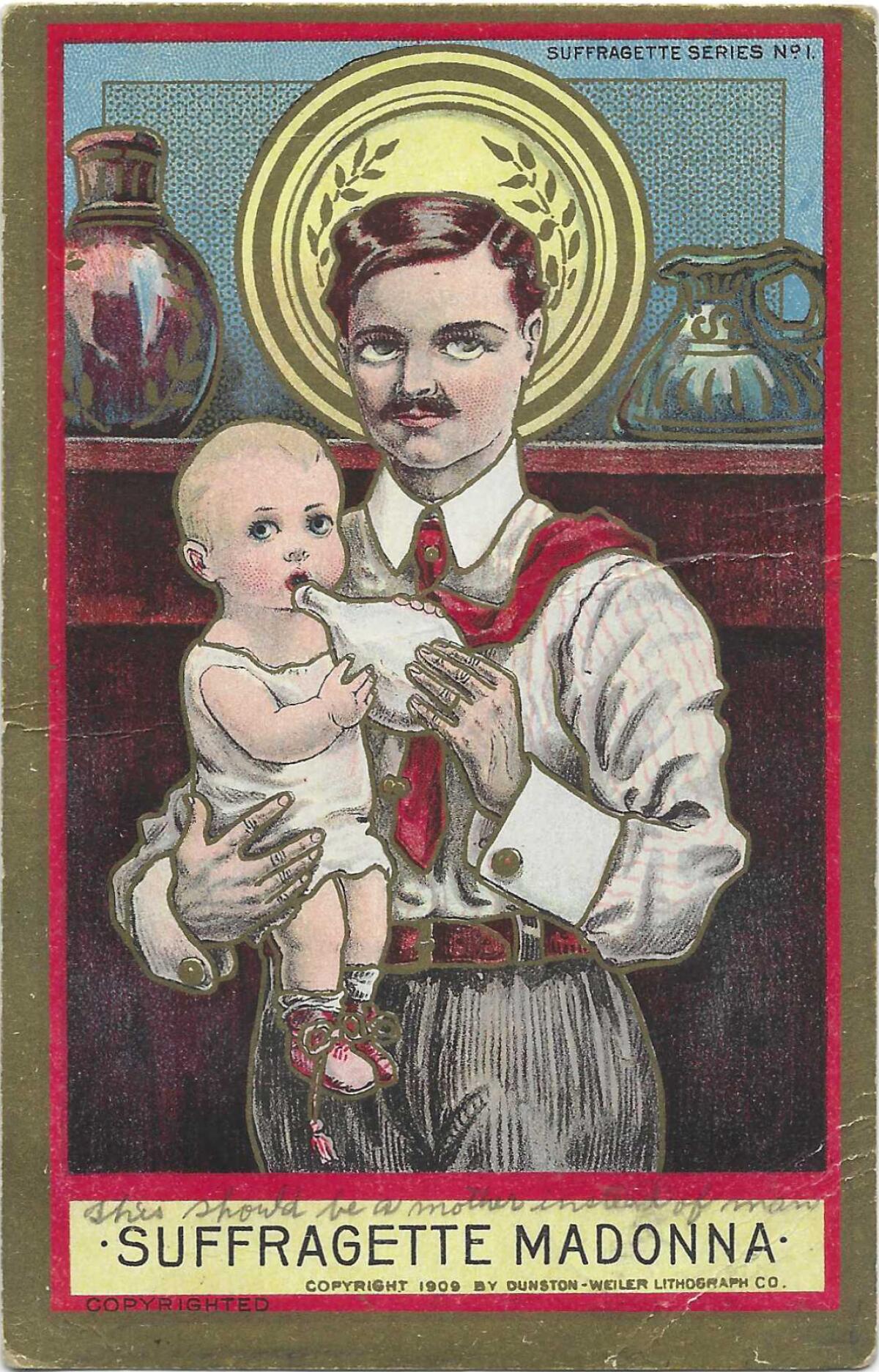

Yeah, about that “mellow radiance”: Postcards served as a kind of social media network of the day, and the cartoonish campaign via postcard against suffrage both here and in Great Britain unwittingly made the case for women.

In imagining a role reversal — women rather than men going out to work and vote, and then coming home to relax and read the paper, and men staying home all day and night with the kids — they showed that men actually did indeed have it good compared to women, whose lives were often round-the-clock drudgery at home.

The postcards also depicted women as so frivolous that they’d vote for the handsomest candidate, so corruptible that they’d give and take bribes for votes.

The one that delivered a gut-punch for me is a card (at the top of this column) showing 20th century suffragists standing before an 18th century George Washington and demanding the vote, and the shocked Father of His Country asking, “Did I save my country for this!” (Memo to George: Hell, yes.)

After women did get the vote, The Times — like lobbyists and politicians — turned out to be … limber. A year or so later, the paper unabashedly asked women to vote for its candidate for mayor, and when that man won, it congratulated women on being “well prepared for the ballot, and they proved yesterday how they understand its power.”

Gee, thanks, General O.

Los Angeles is a complex place. Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.