- Share via

Los Angeles police officers boarded the yacht with guns drawn.

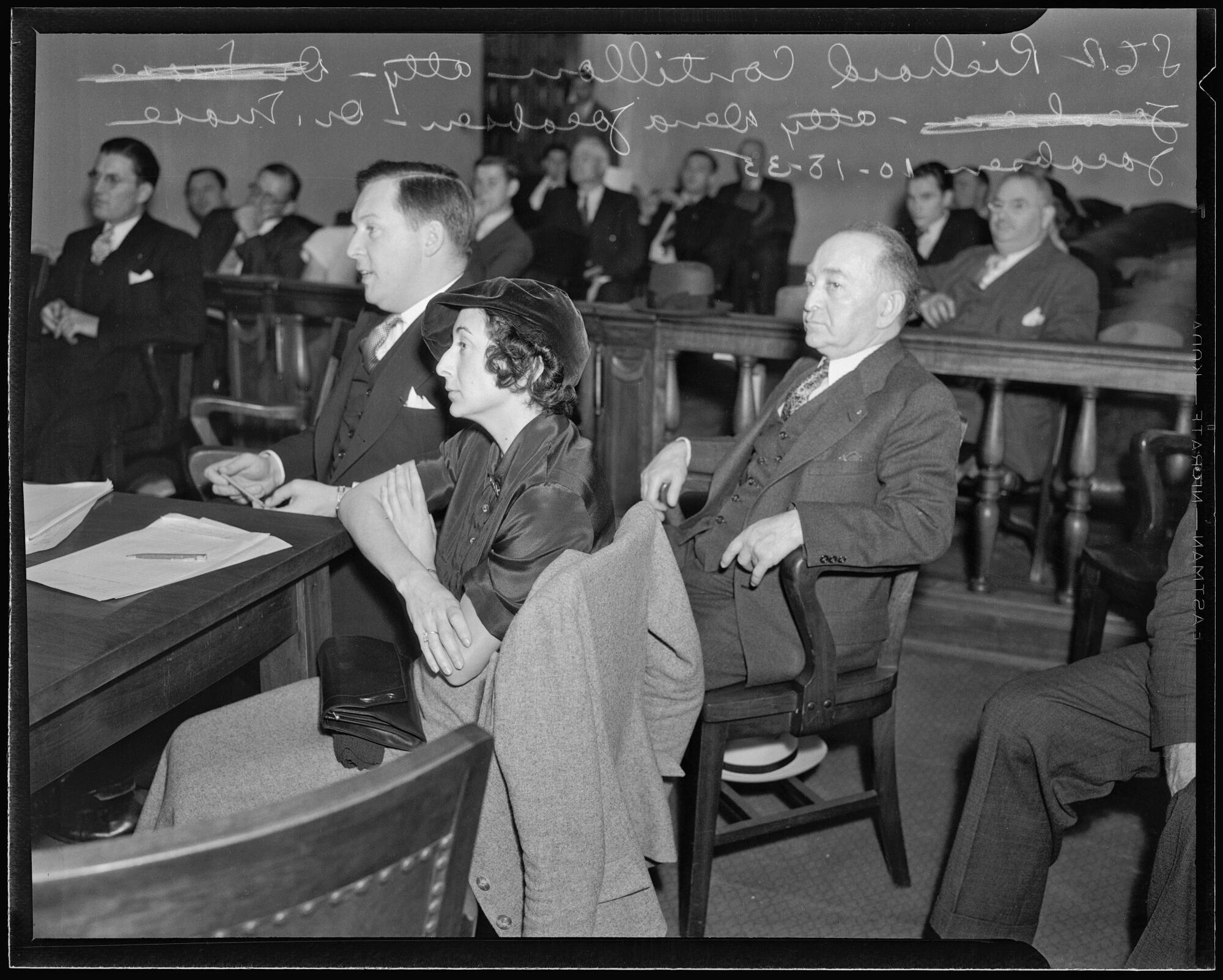

The Westerly had been under surveillance for two months and came with a sordid history. The bodies of a wealthy couple were found after an onboard blast; their daughter was acquitted of murder. Now officers suspected the vessel of being the mobile headquarters of an abortion ring.

Danny Dyer would steer the nearly 50-foot yacht out on the water. His wife would assist another man, who didn’t have a license to practice medicine, as he performed the procedures. They usually charged $450 per operation.

As officers moved in for an arrest that chilly winter morning, Dyer pulled a gun.

“Don’t try it,” Det. Danny Galindo warned Dyer as he raised his firearm. “I’ll kill you.”

It was Feb. 24, 1960, and the abortion squad had arrived.

Housed within the Los Angeles Police Department’s homicide division, the detail investigated what were often known then as “illegal operations.”

Officers on the squad questioned young women who had gone to the hospital for antibiotics after an abortion and were reported to law enforcement. They interviewed loved ones of women who died from botched operations. They went on stakeouts and kept dossiers on hundreds of providers of illegal abortions. They posed as boyfriends or brothers to trap people into confessing.

The team operated for decades, before the U.S. Supreme Court’s Roe vs. Wade decision in 1973 gave women nationwide the legal right to terminate a pregnancy.

Almost 50 years later, on a Friday morning in June, the landmark decision fell. The high court’s ruling has further inflamed debate in states across the U.S. about how to protect — or finally eliminate — the ability to have an abortion.

But it also underscores the potential role of law enforcement going forward. Some states and other jurisdictions want to empower police and prosecutors to enforce laws against abortion while others are pushing to minimize their role.

A 22-year-old woman and an abortion doctor from California played key roles in the legal fight that led to Roe vs. Wade, now struck down.

In a still unsettled post-Roe world, no one knows for sure what enforcement of abortion laws will look like. But L.A. in the 1950s and 1960s offers a hint into at least one possibility.

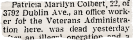

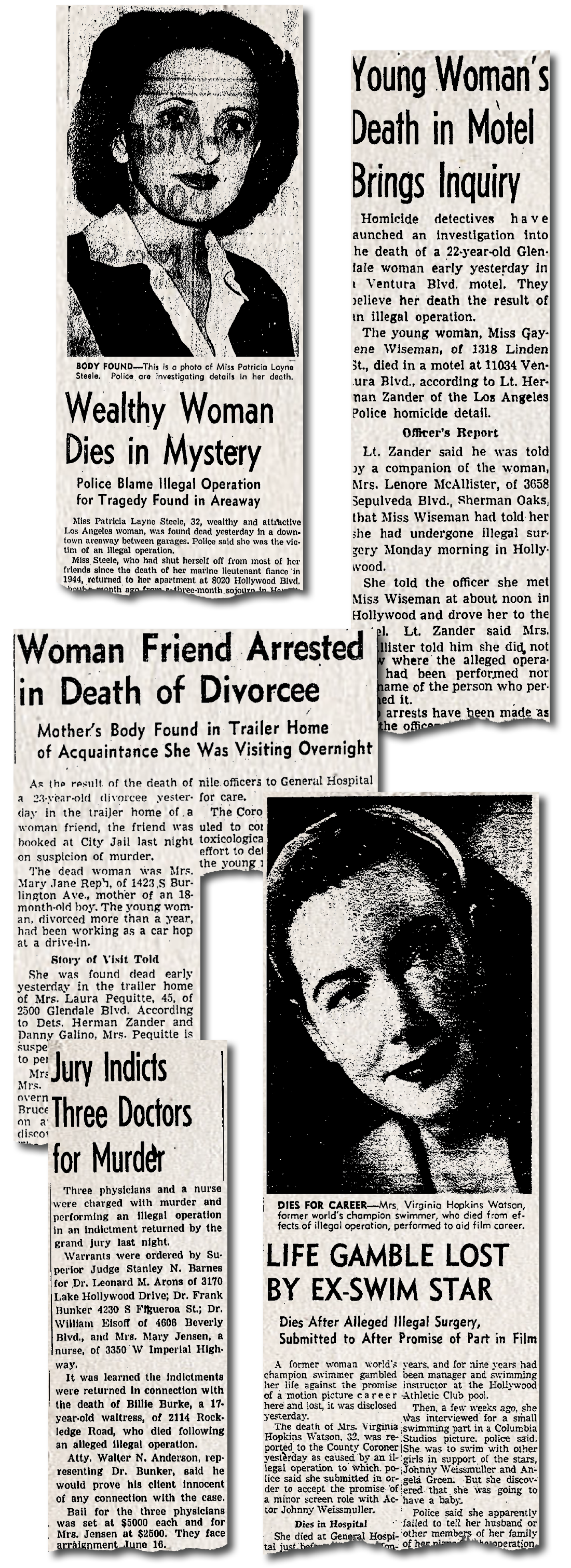

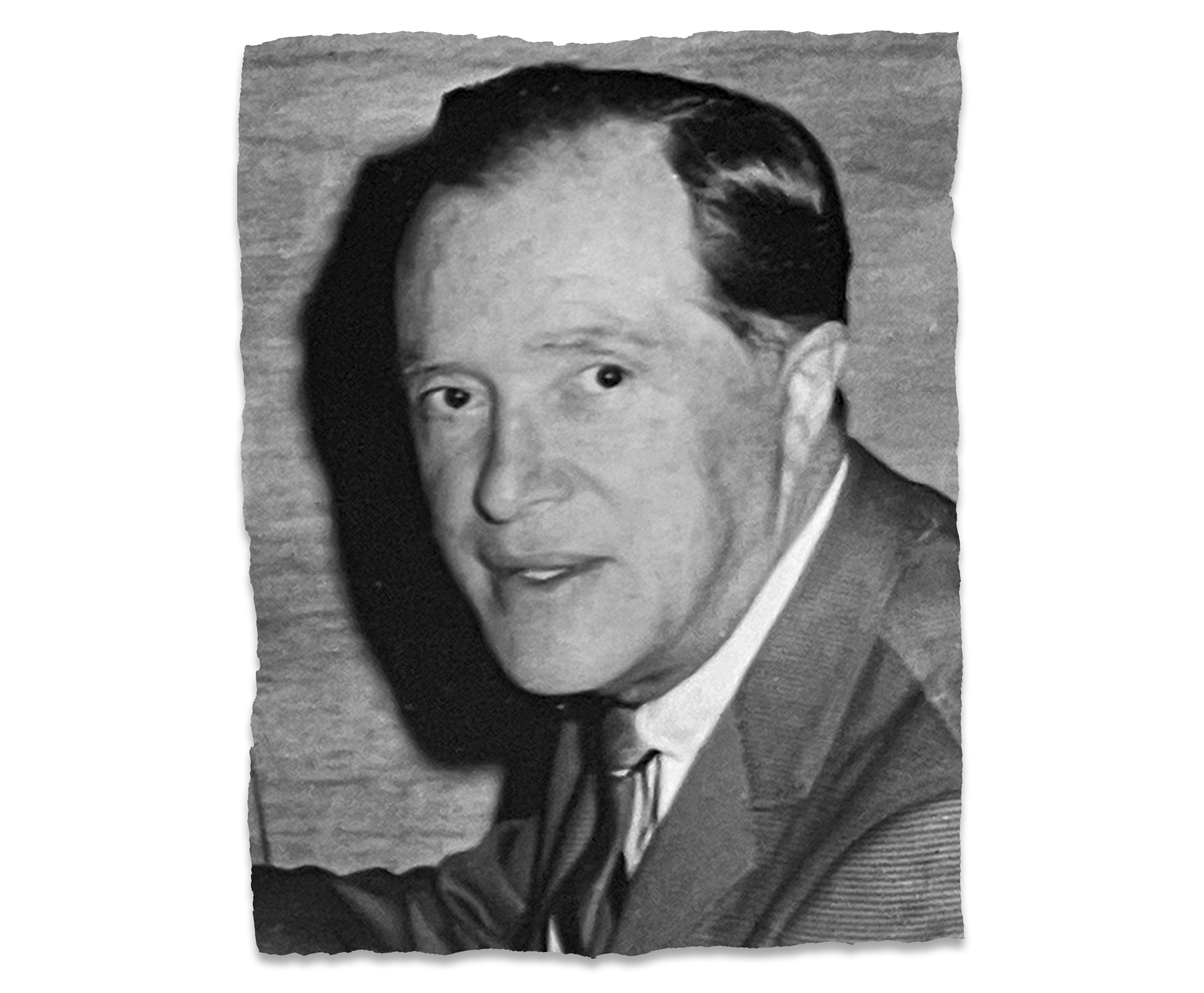

Galindo, 25, was a rookie cop in 1947, the year Elizabeth Short’s body was found, naked and cut in half, in a vacant lot. The Black Dahlia was Galindo’s first murder case.

He was charismatic and good-looking, with curly black hair, striking blue eyes and custom-made suits. He had a hero’s resume: World War II bomber pilot. Plane shot down over Germany. Prisoner of war.

As a homicide detective, he quickly became well-acquainted with death. Standing in a Highland Park ravine, over a headless body discovered by a Boy Scout. Smelling for days the stench of corpses that had decomposed in too-small rooms. Seeing an 18-year-old’s life cut short, after a reserve police officer shot the young man through the neck.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

By 1951, Galindo had taken on an unusual mission: a member of the newly formed abortion squad. His job was to enforce a century-old law that made abortion illegal except to save a woman’s life.

This was a time when television housewives and mothers — in heels, pearls and neatly tied aprons — peddled dreams of the ideal American family. Newspaper headlines read “Housewives Reveal What They’d Like to See in ‘Perfect Kitchen.’ ” A psychiatrist preached in an article that nothing was more important than being a good wife and mother.

But throughout the City of Angels, women and girls desperate to get an abortion were dying as a result of operations often done by people not qualified to perform them.

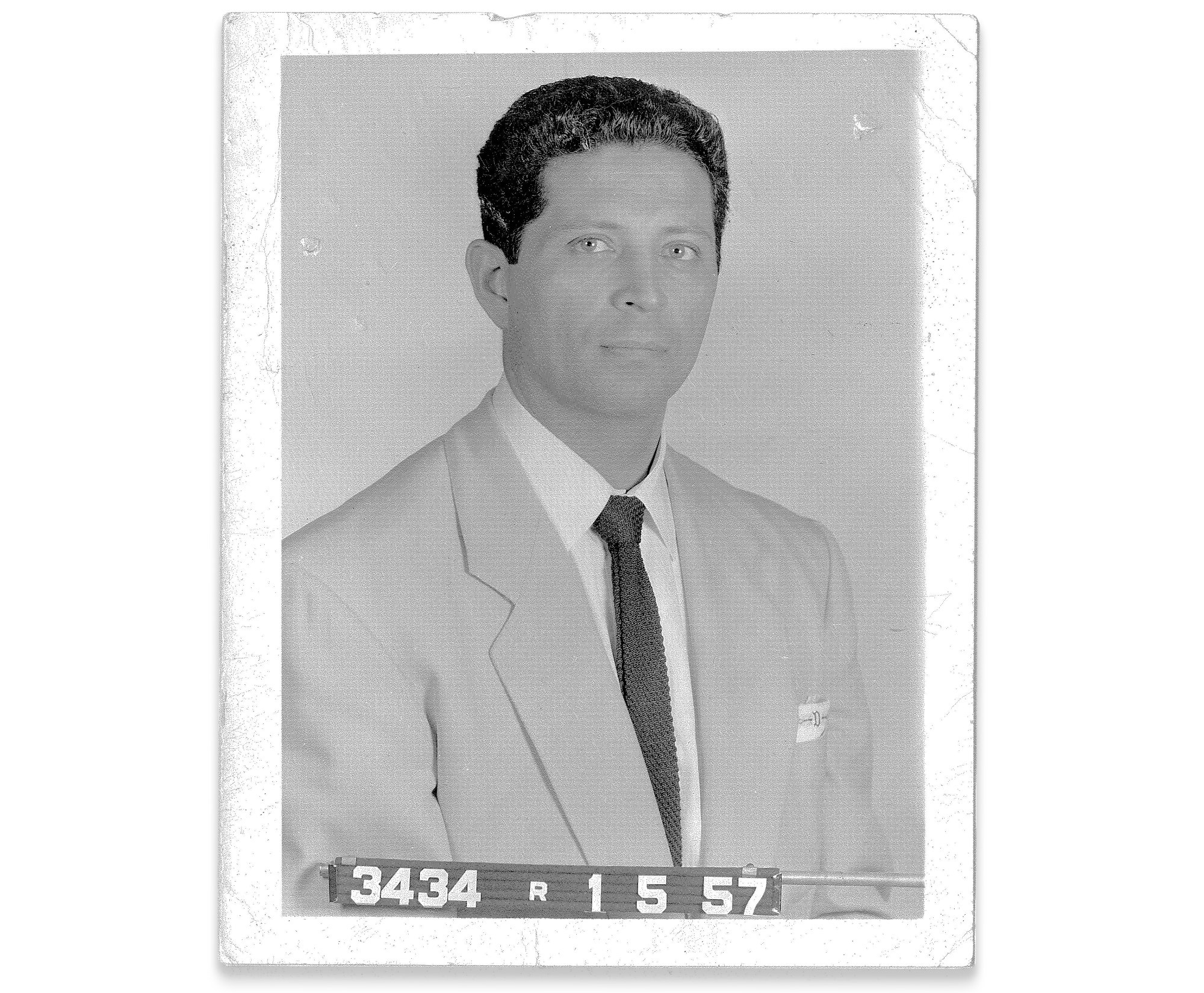

Gaylene Wiseman, 22, who died in a motel room. Brenda Emerson, 16, dumped on a hospital lawn. Patricia Layne Steele, a 32-year-old socialite left crumpled in a dingy alley. Mary Jane Reph, a 23-year-old drive-in car hop, who died in a trailer home while her 1-year-old boy waited in a car outside.

And Virginia Hopkins Watson, a former swimming champion who died in the hospital; the 32-year-old dreamed of a Hollywood career and had gotten the botched operation so she could take a modest movie role.

Women unable to get legal abortions were dying after being injected with disinfectants, overdosing on a too-rapidly-administered anesthetic, suffering a perforated uterus that led to blood poisoning.

The abortion squad fielded calls from hospitals, which were obligated to report any sign of a criminal abortion. As women grievously harmed in crudely done procedures lay on their deathbeds, officers tried to get the names of the person who performed the abortion for their “dying declarations.”

Deaths were the surest way to trigger an investigation, but the squad relied on other means to root out “abortionists” — as the men and women who performed the procedure were called. Scores of women visiting a doctor’s office in one case unleashed a months-long investigation. Detectives communicated through walkie-talkies during stakeouts.

In true Hollywood fashion, Galindo played the role of angry boyfriend when confronting people who performed abortions. He’d tell them his loved one was sick due to the operation and demand money for hospital bills. When the abortionists paid up, Galindo arrested them.

Women in the Police Department helped too. After receiving numerous complaints about a doctor, Josephine Serrano Collier, the LAPD’s first Latina officer, posed as a distressed patient. Dr. Ralph Reed, a practicing physician for 28 years, felt so sorry for her he knocked $20 off his usual $100 abortion fee. Collier paid him in marked bills.

Later, Galindo patted the doctor down, found the cash and arrested him.

“I was sincerely trying to help people in trouble,” Reed, a lieutenant commander in the Navy during World War II, said as he was booked. One paper dubbed him a “bargain basement abortionist.”

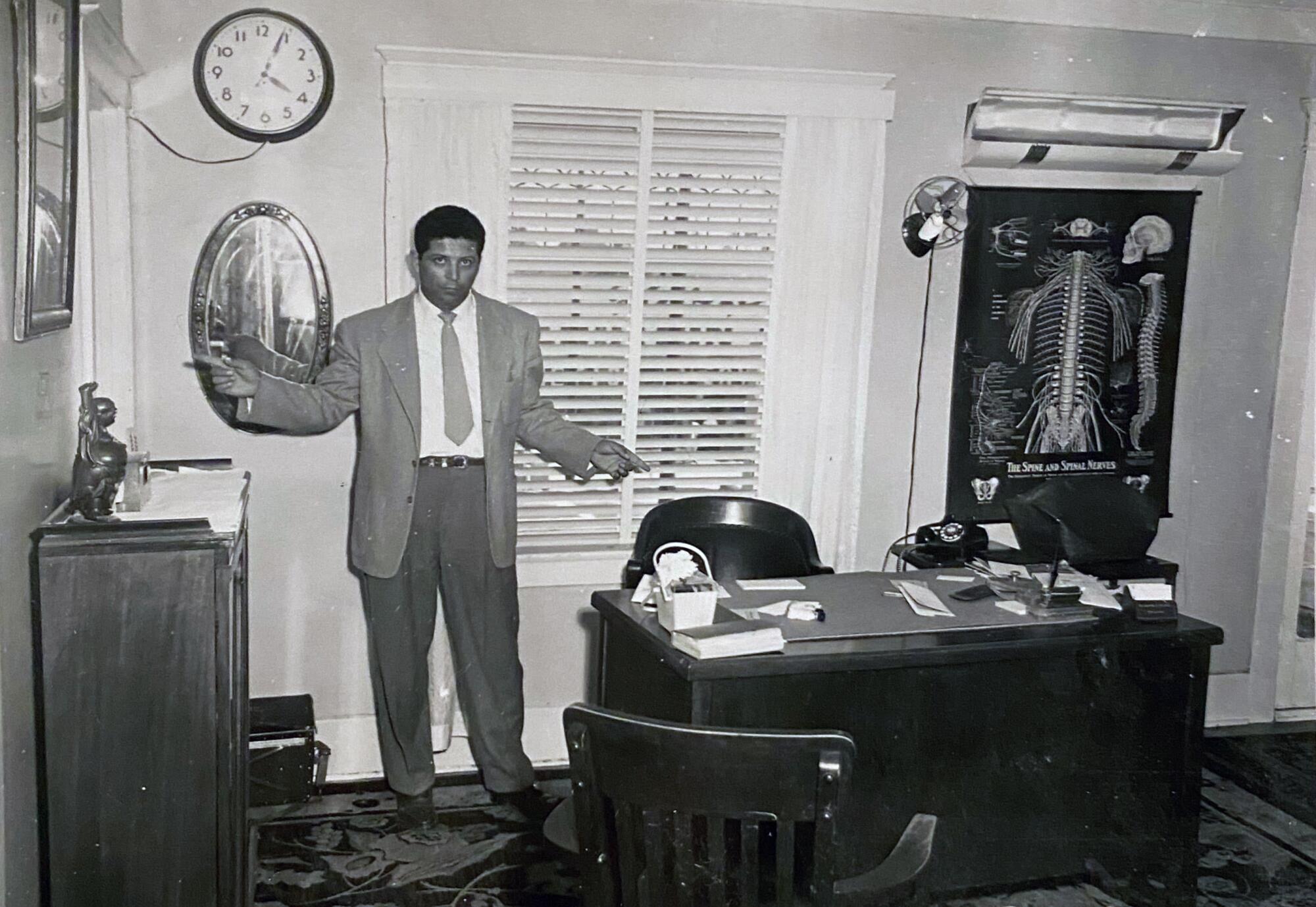

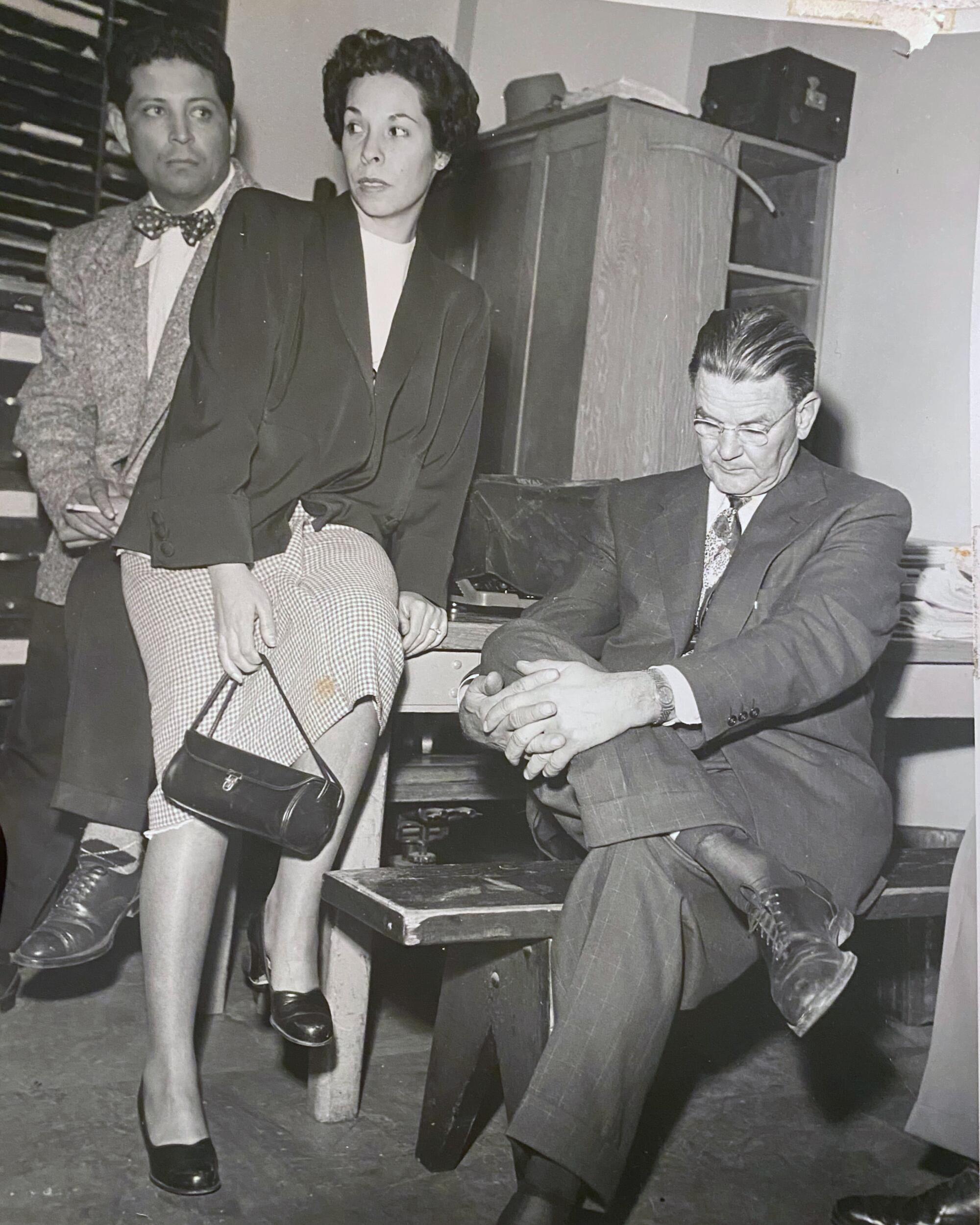

In 1953, Galindo and the team were winding down a six-month investigation into George Davis, a retired doctor in his 70s. Davis had come to their attention after he testified in defense of an abortion suspect found with surgical instruments in her car. Davis said they were his. The woman was acquitted. Davis was placed under police surveillance.

Women, sometimes accompanied by friends, went into his home at night, under the cover of darkness. If they cried out while on his operating table, Davis, a gray-haired bespectacled man, told them he would stop. He didn’t want the neighbors to hear.

Sometimes the women told Davis their stories. One had gotten pregnant while her divorce was not yet finalized. She had a very strict family, and if she were to have the baby, “we would be disgraced and very much humiliated.”

On a Tuesday night in April, Galindo and two other officers raided Davis’ modest Highland Park home. Galindo had been there before, three years earlier, after four bandits bound and gagged Davis, ransacked his home and stole thousands of dollars in jewelry and cash.

This time, Davis was the suspect, not the victim.

In the back bedroom, which Davis used as an operating room, a full-length mirror hid a cabinet containing surgical instruments. One newspaper called it the “butcher shop.” Police arrested Davis and his housekeeper.

Records showed Davis had done nearly 100 abortions in the previous four months on women who had traveled from as far away as San Francisco and Las Vegas. After his arrest, Davis asked Officer Herman Zander if he was being booked for murder.

“Well, doctor, you haven’t lost any girls lately, have you?” Zander asked.

“You know, I have never lost a girl in all my years of practice, either legally or illegally,” Davis replied.

Convicted of abortion, Davis was later freed on appeal.

On a February day the next year, Galindo, part of a four-man raiding squad, went to a Figueroa Street rooming house to arrest Davis again. This time, Davis met them with a tear gas gun in hand.

After he surrendered the gun, police arrested Davis, his wife and a housekeeper who acted as a nurse. Police believed the two women had been helping the doctor perform as many as 30 abortions a month.

Three months later, Galindo helped raid a palatial home in the San Fernando Valley. The abortion ring operating there moved from spot to spot, using a private home, a beach resort and a mountain cabin for operations — performing up to eight a day. Police didn’t know of any deaths that had resulted from the procedures.

By the time he met his future wife, Margie, in 1956, Galindo had been on abortion cases for five years, working those along with murders and rapes. Galindo often found himself interviewing women at the worst moments of their lives.

“He had to gain the confidence of women in a traumatic situation,” Margie said. “He had the ability to do that.”

When John Bartlow Martin, a journalist, met the abortion detail, he called them “expert at persuading girls to talk.” In a three-part series for the Saturday Evening Post, Martin described Galindo as the handsome, likable man who “tries to persuade them gently.” If that didn’t work, his partner, Sgt. Paul LePage, a big man with a cigar, “talks tough to them.”

“It’s like playing a game all the time,” Galindo told Martin. “Any little abortion case is as interesting as a murder.”

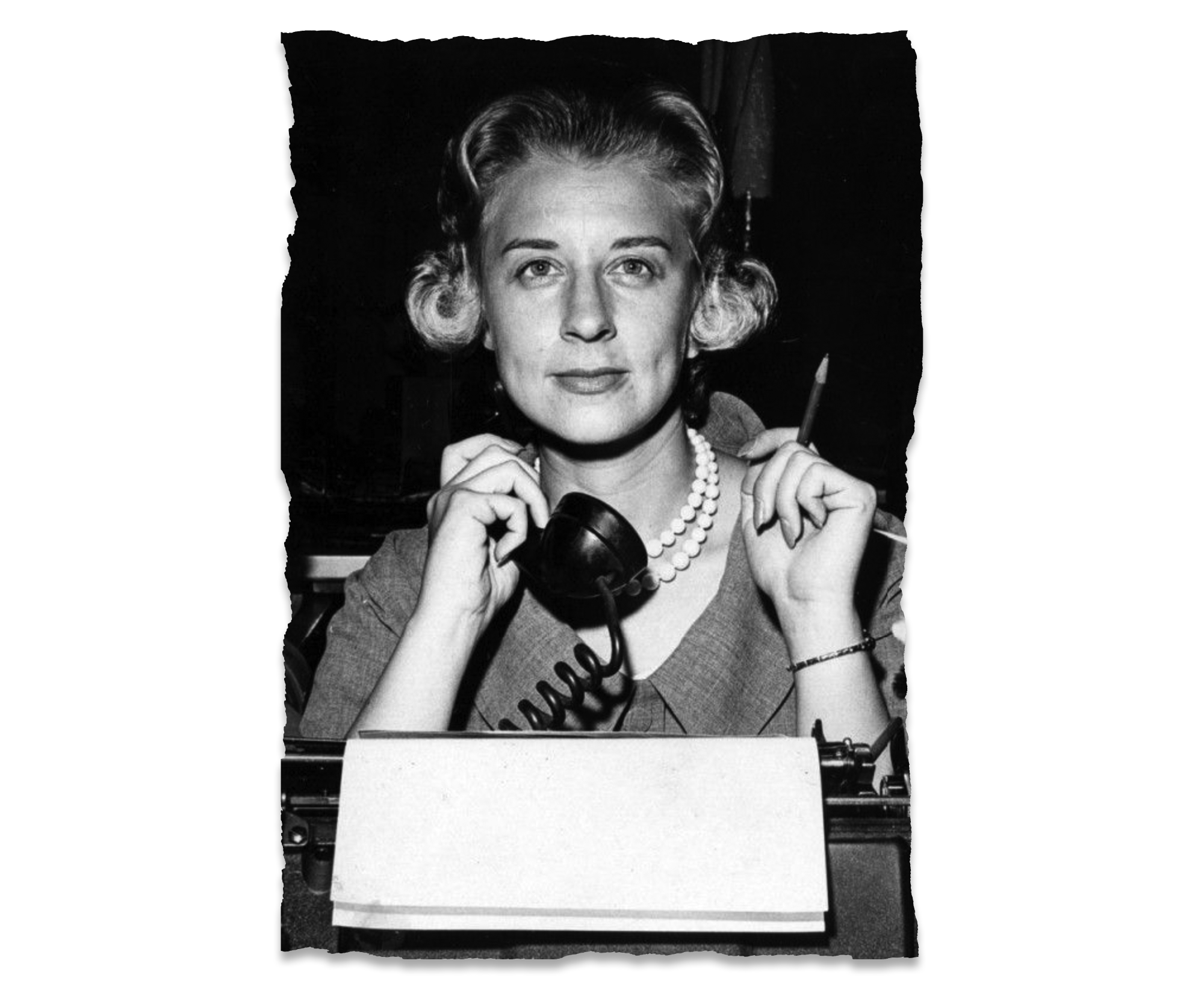

Doris Klein was a reporter at the Valley Times when she started looking into the doctors who performed abortions, the women who contacted them and the police who investigated them. One of the few female reporters covering hard news, she wanted to challenge the societal aversion to talking about the issue.

As Klein looked for sources, someone pointed her in the direction of the LAPD abortion squad. She visited their office, where detectives kept files with cards and background on every complaint about a suspect and records of every case handled.

Galindo estimated that 70% of the women who came to their attention were married. Klein questioned why so many women risked getting the procedure.

“There are about as many reasons as there are women and family problems,” he said. “Most are because they have too many children and can’t stand the financial strain of another.”

The six-man unit — made up of five detectives and a lieutenant — had investigated 80 abortion deaths over the last decade, Klein wrote in a five-part series published in 1961. In the first six weeks of that year, she wrote, there had been three abortion deaths in L.A. County.

The squad’s arrests included chiropractors, osteopaths, nurses, a cocktail waitress, a former real estate agent and a secretary. One abortion ring netted $2.5 million in two years and included a school that taught the procedure. The amount of money earned by those doing abortions ranked only below the take in illegal gambling and narcotics traffic.

Lt. Hugh Brown, head of the squad, told Klein that women who had an abortion were treated “as the victim of a crime.”

“That is,” he said, “she is treated as a witness for the prosecution.”

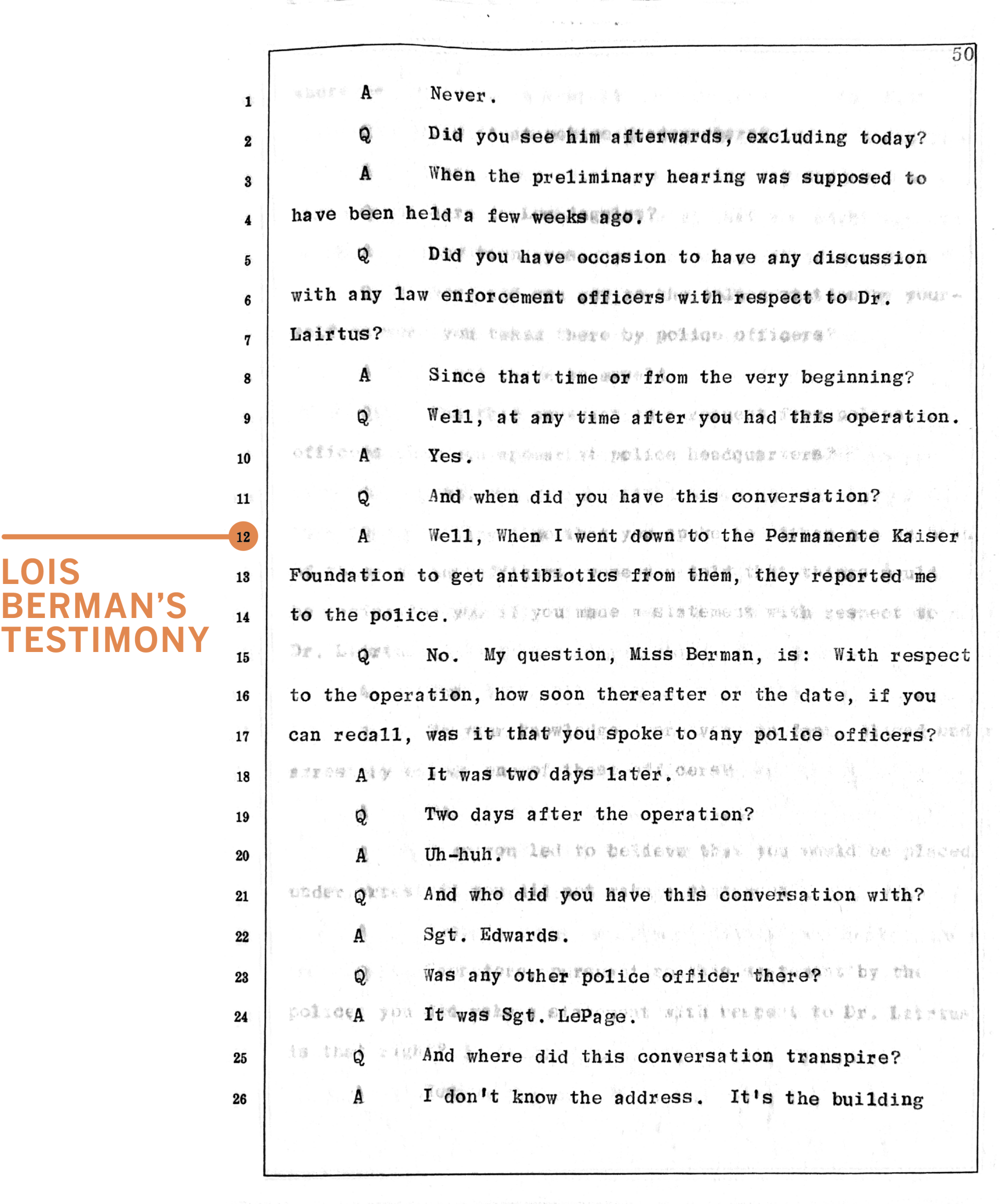

Lois Berman was 19 when she crossed paths with the abortion squad.

As a teenager, Berman, who wore her dark hair in a bouffant, worked part time in a department store along Broadway. The British Invasion was sweeping the nation and, she said, “everything British was popular.” That included her manager, Timothy Harrington, who was from England and had an accent.

In 1966, after she’d left that job, Harrington invited her on a motorcycle ride in the Santa Monica Mountains. Berman didn’t expect anything would happen. The two had sex without using contraception.

“I thought he really liked me and wanted to spend time with me,” she told The Times. “I wasn’t prepared and I didn’t tell him that I didn’t have the birth control device in me, because I felt embarrassed.

“From that one time, I wind up finding myself pregnant. I felt like my whole life was going to be ruined because I wanted to go to college,” she added. “I had all these ambitions for my life, and I knew that guy wasn’t going to marry me. I just foresaw this terrible future.”

Berman spent days shut in her room, crying. Her family was far from wealthy; she, her sister and their parents crowded into a small, two-bedroom apartment. She wanted to have an abortion. She said she “saw no way out” otherwise.

Harrington called a number he’d obtained on the USC campus, where he was studying business administration. He was told they should come to an apartment building on North Kenmore Avenue, where someone named “Grossman” would perform the procedure.

On May 3, the pair went to the apartment, where they met a man who introduced himself as Dr. Grossman. He told Berman it was a very simple operation when done by doctors.

“It is just when quacks do it that people die and get infections,” he told her.

Berman put on an operating gown, lay on a table and put her feet in the stirrups. She closed her eyes tight as Grossman put a mask for anesthesia over her face. A woman assisting in the operation stood by Berman’s side, holding her hand.

She heard the scrape of metal, as something turned around inside her. Within 20 minutes, the operation was over.

Grossman told her that if she were bleeding to go to the doctor and say she had a miscarriage so she could get antibiotics.

“Don’t talk about this to anybody,” he warned. “If I get found out, I won’t be able to help other girls like yourself.”

The next day, Berman went into work. A few hours into her shift, she felt blood seeping through her pink dress, leaving a bright red spot. She made up an excuse to go home, where she changed and then went back to work.

When she got home later that evening, she was bleeding as if somebody had cut her. Nervous, she drove to Kaiser. Rather than lie, she confessed that she had gotten an abortion.

“I don’t want to die here,” she thought to herself. “I’m just going to tell them the truth.”

She thought her admission would remain there.

Afterward, she recalled, the air in the room changed. The gynecology clinic supervisor called the police.

The next afternoon, Berman fearfully entered the downtown police headquarters, dubbed the Glass House for its gleaming facade. On the way over she practiced her story: She’d been blindfolded and had no idea where the abortion happened.

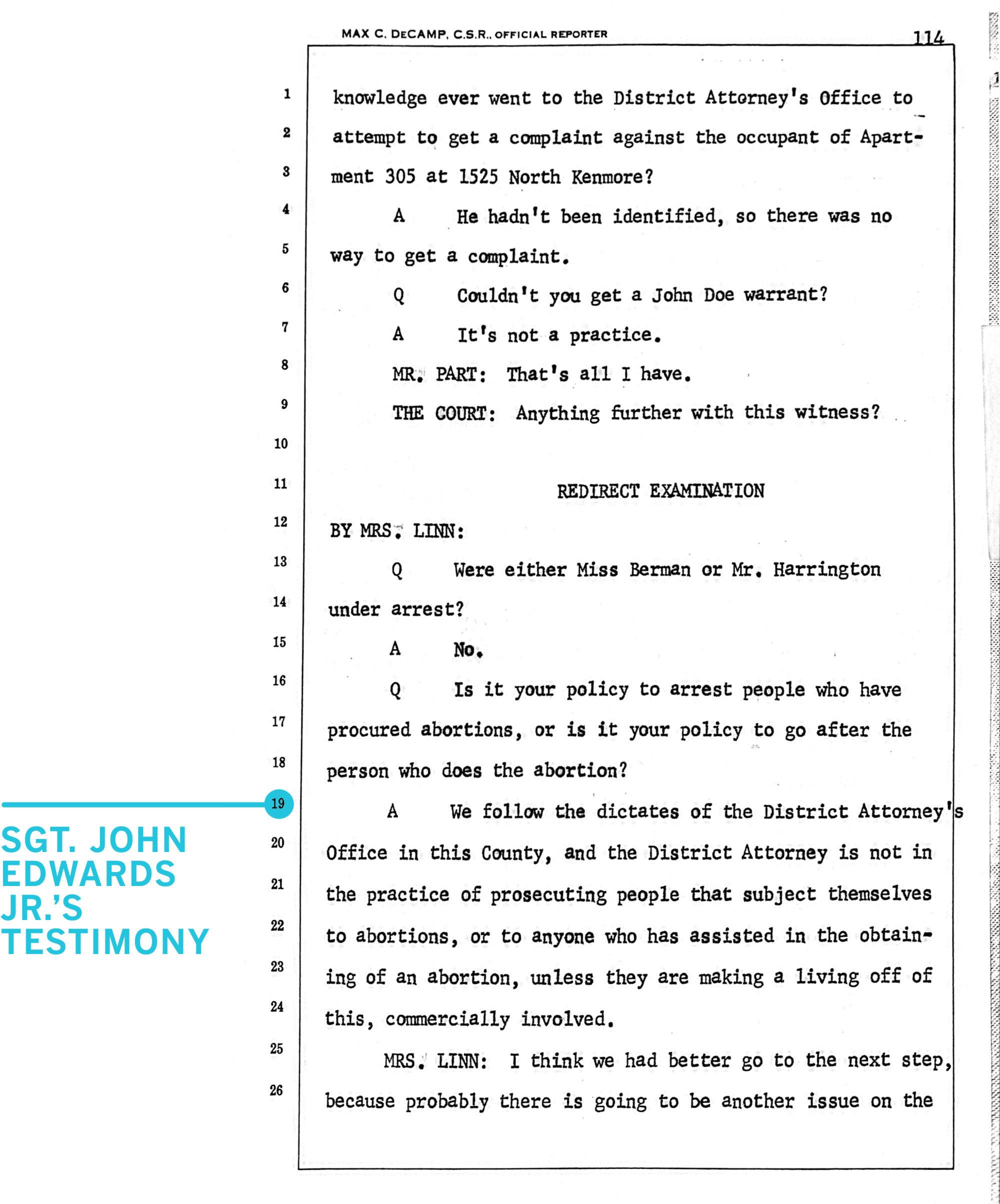

Sgt. John Edwards Jr. and LePage, of the abortion squad, were waiting for her. The stone-faced detectives, in suits and ties, listened as she rattled off her account.

“OK, Miss Berman, you told us this story,” one of the men chided. “Now, how about telling us the truth.”

“I don’t want to die here,” she thought to herself. “I’m just going to tell them the truth.”

The officers rifled through her purse. She had worked for an eye doctor and they pulled out his card and asked if he was involved. They said they would contact him along with everyone in her address book if she didn’t come clean.

“I had kept everything a big secret from my family and friends, and having everyone contacted would have been devastating,” she said.

Berman told them what she knew. That she had entered the apartment building through an alley but didn’t have the address. That the doctor was fair-skinned, around 5-foot-10 with salt-and-pepper hair. That Harrington drove her there.

After staking out Apartment 305, Edwards and two other officers apprehended Grossman on May 10. They soon learned that his real name was Karl Lairtus and that he was licensed to practice medicine in Mexico but not in California. He lived in Chula Vista but had been renting the L.A. apartment for the past year to perform abortions.

“The next thing I know, there was a court date and I was going to have to go testify,” Berman said.

Under cross-examination, Berman said she’d tried to get antibiotics from Kaiser and “they reported me to the police.” She confirmed she’d been led to believe she would be placed under arrest if she didn’t make a statement.

She had to testify about missing her period. About the pinch of pain as she lay on the operating table. About having the police called on her.

When LAPD Officer Phil Barone took the stand, he deciphered a notebook they’d obtained from Lairtus. It included names, days, times and phone numbers. A “3W” listed, he said, meant “three weeks overdue.” Inside Lairtus’ apartment, he testified, were an anesthesia mask, vaginal speculums, curettes, cotton, alcohol and a type of sheet to help drain blood into a pan. He was familiar with the instruments, having made about 100 arrests during his more than two years in the abortion detail.

A couple of times, the defense attorney misspoke and referred to Barone as a narcotics expert.

“Excuse me, I’m sorry,” the attorney said. “I have seen more narcotics experts, your Honor, than perhaps abortion experts.”

Lairtus eventually pleaded guilty to abortion and conspiracy to commit abortion. He then testified against Dr. Leon P. Belous, a prominent Beverly Hills physician whom police accused of having referred patients to Lairtus. Belous was convicted of the same charges.

After Belous’ conviction was upheld by an appeals court in the fall of 1968, he petitioned the state Supreme Court, challenging the constitutionality of California’s abortion law.

In September 1969, in what was touted as a landmark decision, the California Supreme Court reversed Belous’ conviction. Splitting 4 to 3, the high court held that the state’s century-old abortion law was so vague as to be unconstitutional.

By the time the ruling was issued, lawmakers had amended the state’s law to legalize abortion when a woman’s mental or physical health was at risk or if pregnancy resulted from rape or incest. In its decision, the state Supreme Court said it would not rule on the validity of the amended law.

And so, criminalization of abortion continued in California.

In May 1970, LAPD detectives, including LePage, raided a West L.A. clinic. After finding an abortion in progress, they allowed the doctor to finish the operation. They feared if they stopped it, the woman’s life would be endangered, police said. They then arrested the doctor.

Officers also arrested a 23-year-old Cal State L.A. student, who kicked a policewoman and two policemen. The young woman was working at the clinic to save up for an operation for herself, police said.

That was the last LAPD abortion raid that made headlines in The Times.

In January 1973, a U.S. Supreme Court ruling legalized abortion nationwide.

“The police were relieved when it became legal for women to have abortions and they didn’t have to pursue those cases,” said Margie Galindo. “It opened them up to other pressing duties.”

Inside the Los Angeles Police Museum in Highland Park, a display case holds the original booking photo of Richard Ramirez, the serial killer known as the Night Stalker. Another features a now faded red sweatshirt worn by Gregory Powell, one of the notorious “Onion Field” murderers whose 1963 slaying of a Los Angeles officer became a bestselling book, a star-studded movie and changed police practices.

Upstairs are police guns and uniforms spanning decades. In one case, a weathered TV Guide features the stars of “Dragnet,” a series based on the LAPD. One episode starred Marco Lopez in the role of Danny Galindo, as he questioned a victim in Spanish about a shady tow-truck driver.

There’s no visible sign here that an abortion squad ever existed.

LAPD Sgt. Dylan Wells, a police museum volunteer and amateur historian, came across mention of the detail for the first time last year, while researching Josephine Serrano Collier.

A remnant of that time lives on in the LAPD homicide manual, which was most recently revised in 2021. In a chapter titled “Unusual Circumstances,” methods used in abortions are listed, including “the production of a toxic state” and “a mechanical action intended to directly harm the embryo.”

“Murder, as a result of criminal abortion, is practically non-existent under current law and practice,” a paragraph reads. But the information was still being provided “for its value in other death investigations because of the possibility of a change in the law, and for those unique occasions when an unlawful abortion may be performed.”

The way Wells sees it, police must “adapt to something that changes, that includes the criminalization and decriminalization of an act in society.”

After the fall of Roe vs. Wade, Tom Sherman, a Delaware journalist, dug into his collection of antique and vintage historical documents — specifically searching for old New York Police Department manuals he’d rescued from a dumpster a decade earlier.

The NYPD had formed its own squad after an abortion ring bust in the mid-1950s. A 1968 training bulletin titled “ABORTIONS” detailed the use of wiretaps and tails placed on women visiting a doctor’s office for an abortion.

“It was this weird moment,” he said, “of digging it out and looking into the future by reading about the past.”

As of January 2023, 12 states are enforcing a near-total ban on abortion with very limited exceptions, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a research group that supports abortion rights. Doctors who violate abortion laws could face criminal penalties.

An imminent Texas court decision could halt the distribution of a key abortion drug, mifepristone, part of a two-drug combination used in more than half of all abortions in the U.S.

“The Future of Abortion” is a series of stories about the state of abortion is it is challenged in America.

Leslie J. Reagan, author of “When Abortion Was a Crime,” expressed her concern about what could unfold in states where abortion is illegal.

“We have a history of 100 years of what happens when abortion was criminalized,” she said. “It means medical care is varied in the quality of care that people can get. So, it’s unfair and inequitable by class and race and age and all the other variables. It means that doctors and health personnel are acting as police and most concerned about state regulations rather than their patients.”

Berman, now 76, said she kept her abortion “a big secret all my life.” As she got older, she wrestled with guilt over her decision.

‘It was this weird moment of digging it out and looking into the future by reading about the past.’

— Tom Sherman, journalist

She remains conflicted today, calling herself “antiabortion but pro-choice” and stressing that she is against criminalizing the procedure. The environment has changed so much, she said, that she wouldn’t want a return to the time she remembers.

“With Roe vs. Wade, I was really happy that it was legalized, that women wouldn’t have to go through what I went through,” she said. “That they didn’t have to worry, ‘Am I going to get arrested? Am I going to go to jail?’ ”

After abortion was legalized, Galindo kept working homicides and later testified in a retrial of Leslie Van Houten — a follower of cult leader Charles Manson — who was convicted in the killings of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca. Galindo, considered an important member of the Manson murders investigative team, recounted in court seeing the word “war” carved into Leno’s stomach.

He retired from the force in 1977 and went on to work as an investigator for the State Bar of California. He later started a private investigation business. Galindo died in 2010. He was 88.

On a Sunday last fall, Margie pulled out a folder filled with news articles, yellowed with age. One detailed how Galindo had swerved his car in front of a go-between for an abortion ring to stop him from getting away.

Another mentioned the yacht arrests, which Galindo had described to his wife. (“Just one of the ways he could have been killed,” Margie said.) Dyer eventually put down the gun and later pleaded guilty to abortion charges.

Margie and her husband never talked much about abortion, but, she said, “he was happy that he didn’t have to police that anymore.” He felt, she said, that it was an infringement on women’s rights.

“Some of those doctors really thought they were helping the women, and he could understand that,” she said. “It certainly relieved the homicide department when they could concentrate on more horrendous crimes.”

As for where Margie stands on abortion, the once-criminal act her husband spent much of his career policing?

She supports a woman’s right to choose.

She hopes it doesn’t disappear.

More to Read

About this story

This story was reported and written by Brittny Mejia. Library research by Jennifer Arcand, Scott Wilson and Cary Schneider. Editing by Maria L. La Ganga. Photo editing by Marc Martin. Engagement editing by Javier Panzar and Mary Kate Metivier. Story design by Allison Hong, with additional art direction from Nicole Vas. Illustrations by Nicole Rifkin. Copy editing by John Penner. Additional digital help from Lora Victorio and Ben Brazil.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.