- Share via

BIGFORK, Mont. — The college student lay down on an operating table, her legs trembling in the stirrups. The doctor warned her to remain absolutely silent.

She was 22, terrified of needles but prepared to go through with the medical procedure no matter what. Her future depended on it.

“I don’t think I was particularly afraid,” she said. “I had that strong determination. This was the right thing for me to do.”

“This” was an illegal abortion. The year was 1966, the place, California, and Cheryl Bryant was out of options. She had plans to graduate college and become a teacher, and her boyfriend, Clifton Palmer, to be a school psychologist. They were “poor as church mice,” she recalled, and couldn’t afford a baby.

The couple’s search for a way out would ultimately lead to the arrest and conviction of Dr. Leon P. Belous for conspiracy to commit an abortion. To their testimony in front of a grand jury. And to a battle that would wind its way up to the state Supreme Court.

Cheryl could never have anticipated that the legal fight over her abortion would help lay the groundwork for Roe vs. Wade. Or that the U.S. Supreme Court would cite that California case in handing down its landmark 1973 decision legalizing abortion.

Or that California, where she grew up and sought help as a desperate college student, would now be positioning itself as a sanctuary state for those in need of reproductive care, with Roe struck down on Friday.

::

They wore the passage of time on their faces. In the smile lines that creased their cheeks and once-blond hair that had faded to a snowy white.

Cheryl and Clifton Palmer, now in their late 70s, sat in their Montana living room, their elderly cattle dog, Pepper, snoring softly at their feet. As they spoke, each looked to the other to fill in the gaps of their life stories. After nearly 56 years of marriage, there wasn’t much they hadn’t gone through together.

It was May 16, two weeks after a leaked draft Supreme Court opinion signaled that Roe vs. Wade could soon become history. About a week after Montana Sen. Steve Daines stood by a poster showing a turtle hatchling next to babies and argued that, under an abortion bill proposed by Democrats, sea turtle eggs would have more protection than human fetuses.

Like millions of others, they had been following the news about the fate of abortion. The draft opinion, written by Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr., slams the 1973 Roe decision and a subsequent one — Planned Parenthood vs. Casey — that upheld it.

“Roe was egregiously wrong from the start. Its reasoning was exceptionally weak, and the decision has had damaging consequences,” Alito wrote. “And far from bringing about a national settlement of the abortion issue, Roe and Casey have enflamed debate and deepened division.”

The Supreme Court’s final decision was handed down Friday.

“I don’t know why this thing is even a political issue,” 77-year-old Cliff remarked. “It should just be between a woman and her doctor to figure it out.”

No state has had a bigger impact on the direction of the United States than California, a prolific incubator and exporter of outside-the-box policies and ideas. This occasional series examines what that has meant for the state and the country, and how far Washington is willing to go to spread California’s agenda as the state’s own struggles threaten its standing as the nation’s think tank.

The couple had felt the same way five decades earlier, when they’d decided to take their future into their own hands.

They scrunched up their faces, their blue eyes fixed in concentration, as they grasped at memories more than half a century old from a chapter of their life they rarely revisit.

“We were so busy in school, we put it behind us and I don’t think I ever really thought about it much,” Cheryl said.

Behind the 78-year-old, near the front door of their ranch house here in the small town of Bigfork, hung a sign that read: “Clifton Palmer, minister.” She had taken it from the church where Cliff had once worked.

The abortion, as Cliff puts it, was “a blip” in their lives.

“I guess we’re fortunate that we weren’t burdened by a lot of religious beliefs or guilt over this,” said Cliff, who spent six years as minister of the Foothill Community Church of Religious Science in Auburn, Calif. “I think you make your choices as best you can in the moment. And then you look forward and you don’t regret anything that’s happened to you.”

::

Cheryl was a 17-year-old high school student in South Pasadena when she first got pregnant.

She wore a girdle to hide the weight gain. When her mother learned of the pregnancy, she gave Cheryl castor oil, hoping to flush the baby out. When that didn’t work, she sent Cheryl to a Florence Crittenton home, a shelter for “unwed mothers.”

Cheryl gave birth to a son in July 1961.

She signed adoption papers, but the baby’s father wouldn’t. Rather than leave the baby with him, she cared for her son herself. She named him after her mother’s movie actor crush, Tyrone Power.

The second time Cheryl got pregnant, she was a student at what was then known as California State College at Los Angeles. She was dating Cliff, a cherub-cheeked man she met in class. They both had jobs and were putting themselves through college.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

“It was just horrible timing,” Cheryl said. “It would just put us in a bad place, a real hardship, to try to have a baby and interrupt our dreams and our parents’ dreams of both of us getting college degrees.”

She had missed her period in April 1966. Cheryl’s family doctor gave her pills that would induce menstruation if she wasn’t pregnant. She took them religiously for a week. Nothing happened.

“The only thing that was left for us to do, and we were determined we were going to do it, I was going to get an abortion,” she said.

But in California, an 1850 law made it a felony to perform, provide or procure an abortion unless necessary to preserve a woman’s life. For decades, women had been crossing the border into Mexico to get the procedure. Clandestine abortion rings operated throughout the state.

Doctors were being put on trial. In March 1966, a doctor was ordered to begin serving a one-year jail sentence for a conviction on three counts of performing an illegal abortion.

In 1966, L.A. County doctors said at least 2,500 women were admitted to the general hospital each year in need of treatment following an “incomplete abortion,” according to a Times article.

Doctors were required by law to report to police any case in which they saw an indication that an abortion had been performed. If the investigation revealed where the abortion was done, that information was sent to local law enforcement. L.A. police records tallied 40 to 60 arrests and prosecutions of providers in the city each year.

There were about 70 maternal deaths a year in the county, about 25 of which were the result of abortions, according to state data at the time.

Getting an abortion meant risking death and being willing to break the law. Cheryl and Cliff had no criminal records. Had never gotten so much as a traffic ticket. They didn’t know where to start.

Then, one night, while watching “The Louis Lomax Show,” a weekly news and public affairs program, they heard Belous speak. He was advocating for a change in California’s abortion laws. They called the program and got his number.

In a call to Belous, Cliff explained they were at their “wits’ end” and asked for Belous’ help. At first, Belous said there was nothing he could do. In that case, Cliff told him, Cheryl would go to Tijuana for an abortion.

Belous was familiar by then with the abortion business in Mexico. And he knew that in going there the young woman would be taking an enormous risk.

He agreed to see the couple.

::

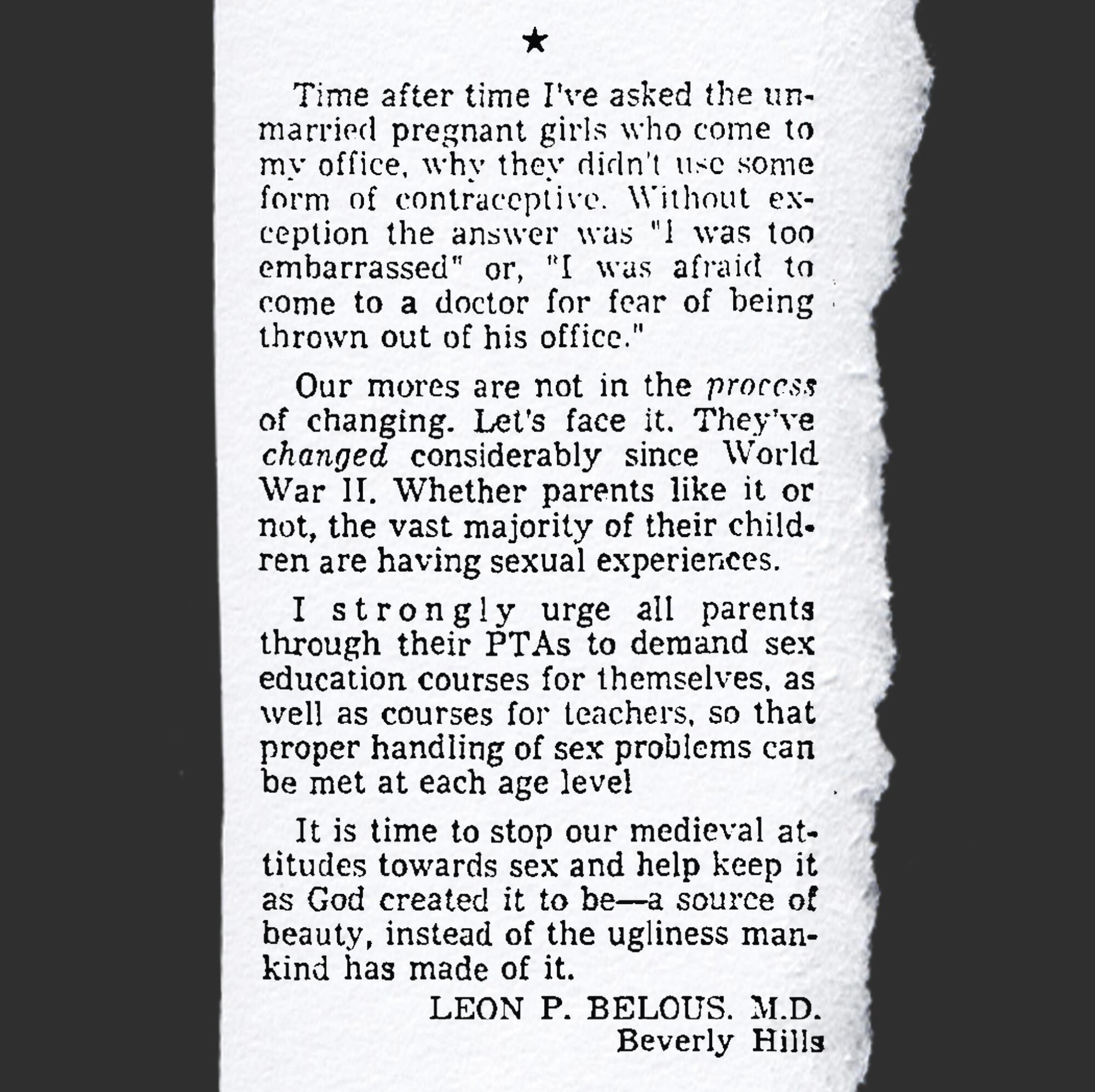

“Unwanted pregnancies, that cause thousands of needless deaths and about a million criminal abortions a year, must be recognized as a social disease and be treated as such. These women are not criminals, they are human beings who are entitled to protection instead of being ‘thrown to the wolves,’” Dr. Leon P. Belous, Los Angeles Times, Aug. 4, 1962.

Belous was no stranger to a woman’s desperation.

He had been practicing obstetrics and gynecology in California for more than three decades after his family emigrated from Russia. He’d entered the field, his granddaughter Amy Stone said in a recent interview, because he felt “he could bring the most good in that area.”

“He took the counseling part of his medical approach really seriously and discovered just how deeply women were being hurt by not being heard,” Stone said. “And the decisions that they were making ... were the ones thrust on them by a very male-dominated society. The more he learned from talking to women, the more of an advocate he became.”

Belous became a leading crusader against the state’s antiabortion laws. But few people knew his personal connection to the fight.

When his daughter, Dionne, was a college student in the 1950s, she confided that she had gotten pregnant with a boyfriend with whom she saw no future.

“How would you feel if you dropped out of college?” he asked.

“Devastated,” Dionne said.

“Well, would you want to marry this man? Would you want to have a family? Would you want to be a wife and mother?” he went on.

“Those were all questions my mother had a one-word answer to, and that was ‘no,’” Stone said.

Dionne got an abortion. Her father supported her.

Throughout the 1960s, Belous wrote several letters to The Times. He advocated for birth control, called for sex education courses in schools and decried the death and disease that stemmed from illegal abortions.

He called California’s century-old abortion law “rigid” and “antiquated” and supported a modification that would permit therapeutic abortions in cases of rape or incest or for pregnancies that endangered physical or mental health.

“I have seen many pregnant girls and women who should have had abortions, but which our laws would not sanction,” he wrote in a 1962 letter. “Because of the rigidity of our abortion laws, I have seen some of these patients die — not without something dying a little inside me too.”

Belous participated in a 1963 public forum titled, “Should abortion be legalized,” which he said should more appropriately be called, “Man’s inhumanity to women.” On the panel, he talked about his first patient with an unwanted pregnancy, “who left my office and ended in a grave.”

The 24-year-old had three children, an alcoholic husband and no money, he said. She pulled together $50 to get an abortion from someone who wasn’t a doctor. He perforated her uterus and damaged her bowels. She died of blood poisoning.

The list went on and on. The 24-year-old who had a corrosive agent injected into her uterus to induce an abortion, but which led to her death. The 25-year-old whose husband used a bicycle pump to push air into her uterus, with fatal consequences.

“At present we have no place where a woman can come” for help, he said. “She is rejected by society and the medical profession. In her hour of greatest need, she is forced to hunt for a quack abortionist on her own.”

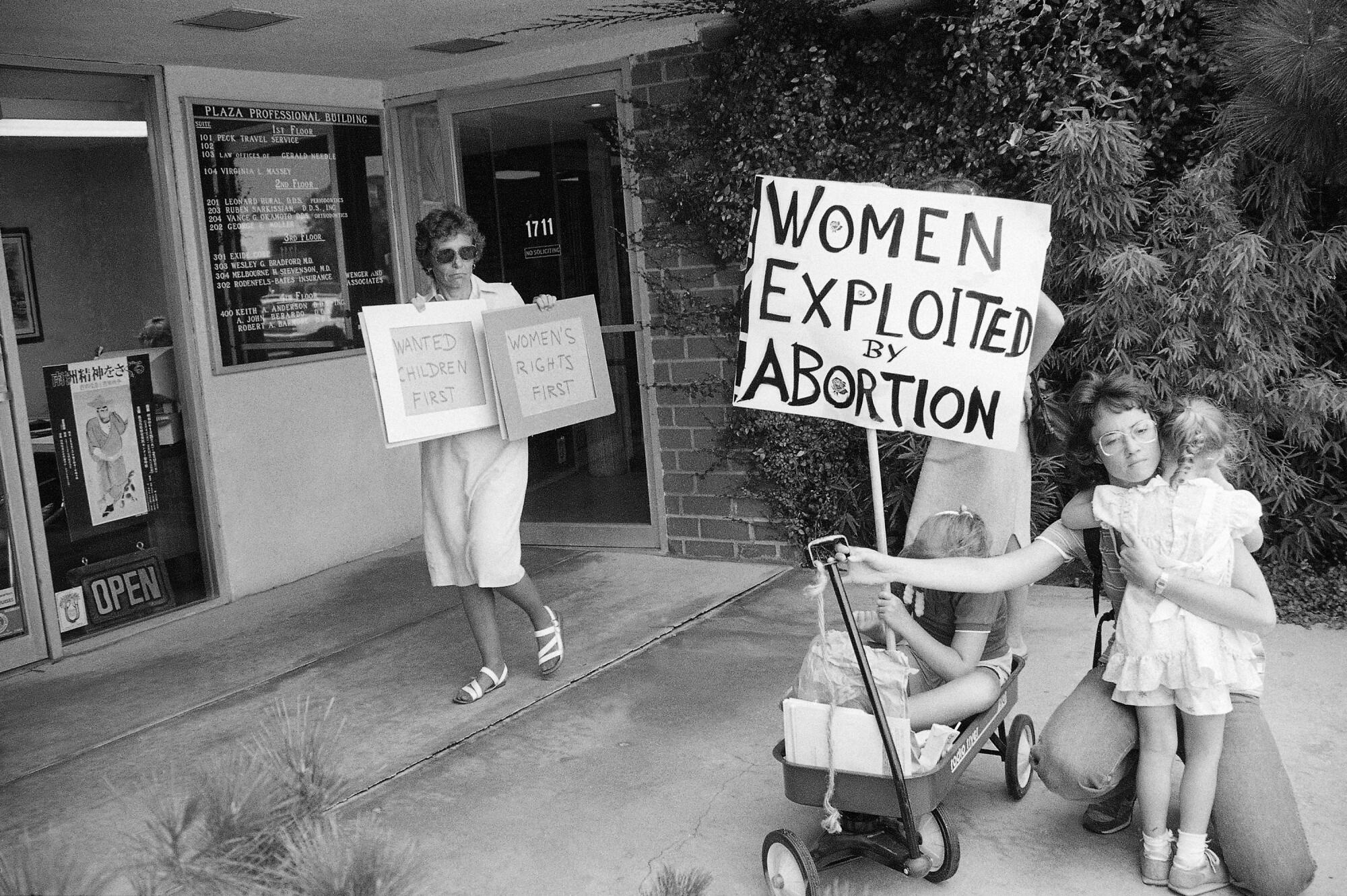

On the same panel, Dr. Robert Hood, a general surgeon, argued that abortion “violates one of the fundamental tenets of Western civilization: Thou shalt not kill. It promotes promiscuity and lessens the sanctity and worth of marriage.” He added that “the unwanted child in one home may be the highly desired child in another home.”

In response, Belous said, those who oppose him, like Hood, had never offered constructive suggestions on what to do about women who go to abortionists and die.

“They just sit back and just have philosophical discussions about the moral issues and so on, but in the meantime there’s death and destruction going on,” he said.

When Cheryl and Cliff visited Belous’ Beverly Hills office nearly three years later, in April 1966, he warned the couple about the dangers of criminal abortions.

He didn’t do illegal abortions, he explained. He was trying to liberalize the law, he said, not break it.

In tears, Cheryl and Cliff explained that having a baby would derail their futures. Their story was reminiscent of Belous’ daughter’s. They too were of college age. They too were determined to graduate. They planned to go to Tijuana for the abortion if necessary.

Belous wrote down the number for a man named Karl Lairtus. He had met Lairtus while in Tijuana and had seen him perform skilled and safe abortions. The doctor had since moved to Los Angeles.

He wrote Cheryl a prescription for antibiotics and told her to return for an exam after the procedure.

::

The young couple pulled up to the Hollywood apartment building in Cliff’s blue Volkswagen Beetle on May 10, 1966. They carried $500 in an envelope to pay for the abortion. Cliff had sold his motorcycle to raise the money.

Cheryl spotted a police car parked across the street, a few houses over. Three officers were inside. Cliff thought they might be wearing suits. The couple wondered what was going on.

In fact, officers from the Los Angeles Police Department abortion detail had been staking out the apartment complex for the last hour. Days earlier, they had gotten a call from a clinic supervisor at a Kaiser hospital. She reported a woman asking for antibiotics after an abortion.

Police had questioned the woman and learned the location: 1525 N. Kenmore Ave., Apt. 305. The name on the mailbox, police said, was Jack Grossman. But it belonged to Lairtus.

Cheryl and Cliff arrived shortly before noon. When Lairtus opened the door, he ushered them into the living room. He checked off Cheryl’s name in a little book and asked for the cash.

Cheryl changed into a white smock and went into the bedroom. Lairtus told her to get on the portable operating table and put her feet in the stirrups. If she made a sound, he warned her, “I’m stopping wherever I am.”

Lairtus gave her a “gas mask” to slip over her face. He told her that it would deaden the pain and — when she needed it — to inhale deeply. Soon, she felt a pressure-like pain as he inserted a cold instrument into her vagina. She grew woozy from the mask and her legs grew wobbly and tired. She kept her eyes clenched shut.

When it was over, Lairtus brought her a Coke from the fridge to settle her stomach. As she lay resting, the doorbell rang.

The Spitzes, a married couple, had arrived for their 1 p.m. appointment. But when Lairtus opened the door, police officers were right behind them. Sgt. Phil Barone stepped across the threshold and spotted Cliff seated on a divan.

Barone read Lairtus his rights. The officers patted him down. Lairtus, who was licensed to practice medicine in Mexico but not in California, handed police an appointment book. It included the names and ages of women — and the names of physicians, including Belous.

When Barone went to the back bedroom, he spotted Cheryl lying on one of the beds. After he questioned her, she confirmed that she’d just gotten an abortion.

The police took Cheryl to the hospital, but no one offered to treat her, she said.

The couple told the police Belous had provided them the number to call for the procedure. That same afternoon, Barone and other officers arrested the doctor at his Beverly Hills office. The charge: abortion.

It would be much easier on Cheryl and Cliff, the police said, if they cooperated with authorities. But that meant testifying for the prosecution against Belous.

Cheryl dreaded the idea. In her opinion, the doctor had saved her life.

::

On an August day in 1966, in the grand jury hearing room in Los Angeles Superior Court, Cheryl raised her right hand and swore to tell the truth.

She described going to Belous’ office months earlier, fearing she was pregnant.

“I told him that … I couldn’t have this child,” she testified. “I wasn’t financially or mentally equipped.”

Cheryl testified Belous had told her there was no way to get a legal abortion, that he couldn’t help. But, she said, “I kept persisting.” Eventually, “he finally gave me the phone number of a doctor who would perform an operation.”

When Barone took the stand, he said he’d been on the abortion detail for two years and two months. The unit made about 50 arrests a year related to criminal abortions and probably handled 100 to 150 investigations a year, he testified.

The LAPD officers learned from Lairtus that Belous “was referring patients to him and they would split the fee,” Barone testified. Belous denied receiving any money.

The bulk of Belous’ defense rested on his belief that Cheryl and Cliff would do anything to terminate the pregnancy, which could involve butchery in Tijuana or self-mutilation and put Cheryl’s life in danger.

On Aug. 11, the grand jurors decided enough evidence existed for Lairtus and Belous to go to trial.

After testifying, Cheryl and Cliff moved on. They got married on Sept. 11, 1966, in the Little Church of the West on the Las Vegas Strip. Cheryl’s mother had been married in the same place.

Cheryl wore a chic white lace sheath dress. She was still in school working for her teaching credential. Cliff, who’d gotten his bachelor’s in psychology, was enrolled in graduate school. The two stayed at the newly opened Four Queens Hotel and Casino.

Cliff’s hometown newspaper carried the news under the headline: “Clifton Palmer Claims Bride in Vegas Rites.” The announcement ran under a photo of the couple arm in arm, grinning. Cliff adopted Cheryl’s child, Tyrone, who was a toddler by then.

The couple put the case out of their minds and focused on their future.

A Los Angeles Superior Court jury convicted Belous in January 1967 of abortion and conspiracy to commit an abortion. He was placed on probation for two years and faced a $5,000 fine. He decided to appeal.

Stone said her grandfather wanted to fight what he felt was a wrongful conviction and to protect his reputation in the community. He also worried that his conviction would make it harder for other doctors to stand up to “legal bullying that was going to further threaten the lives of women already traumatized by the stigma of an unwanted pregnancy.”

As the months wore on, the tension built. As threats rolled in, the phone in the Belous house rang and rang. Strangers shattered the family’s windows. Once, a rock landed in the middle of the dining room table, a piece of paper tied around it with twine.

“I couldn’t read much, but I knew how to read D-I-E,” said Stone, who was 4 years old at the time.

The family stopped eating in the dining room, because the windows were too close to the table. At one point, Belous’ wife, Julie, collected the rocks and arranged them into a morbid centerpiece on the dining room table.

Belous received death threats every day. At his office. His clinic. His home. He found notes on his car in the morning.

At one point, Stone worried that her grandfather was contemplating suicide. He sat her on his lap and asked if it’d be OK if he went away “for a very long time.” No, she told him, “you can’t go. I need you, Papa.”

“He made the decision to stay and fight,” Stone said.

After his conviction was upheld by the Court of Appeals in the fall of 1968, Belous petitioned the state Supreme Court, challenging the constitutionality of California’s abortion law.

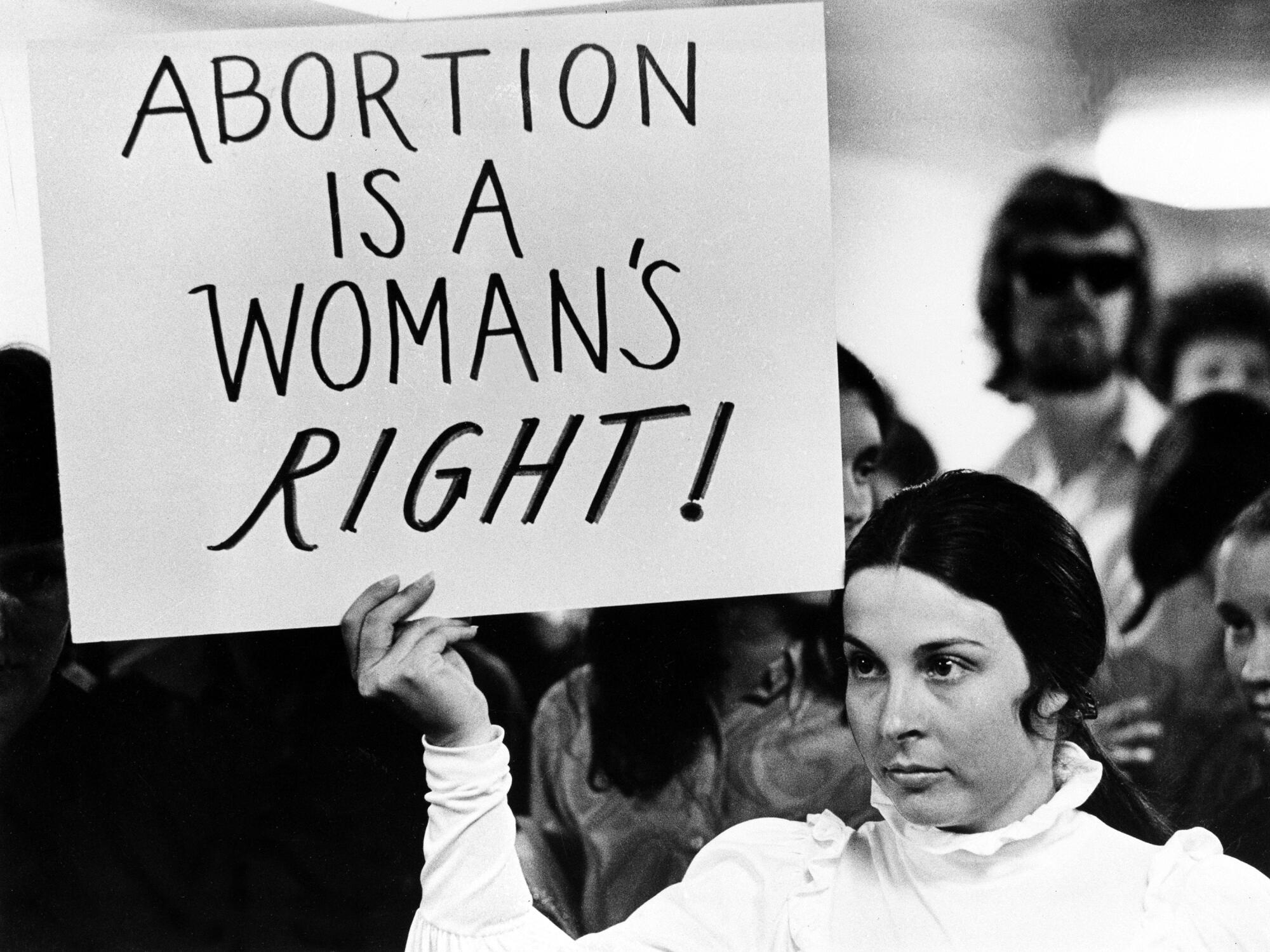

The petition was prepared by attorneys with the American Civil Liberties Union. It declared that the right of a woman not to be compelled to bear a child must be considered a personal right of the most intimate and highest nature.

One amicus brief in particular, largely written by ACLU volunteer attorney Norma Zarky, cited the violation of the 1st Amendment’s prohibition against laws respecting an establishment of religion. It also argued that the law was an arbitrary invasion of the fundamental right of women to determine when to bear offspring and physicians’ rights to prescribe for their patients.

“The challenged statute violates the private right of a woman to determine whether or not to bear a child,” the brief stated.

The state attorney general’s office, in a brief filed in opposition to the appeal, said “all laws restrict one’s freedom to a certain degree.”

“In the present case, we must weigh the life of the unborn child against the mother’s right to freedom of action,” the brief stated.

Cheryl and Cliff, both wrapped up in school and work, were suddenly splashed across the front page of The Times. Cheryl stole all the copies she could find and hid them from her family.

The case was argued before the California Supreme Court in March 1969. The ruling didn’t come until September.

In what was touted as a “landmark decision,” the high court reversed Belous’ conviction. Splitting 4 to 3, the high court held that the state’s century-old abortion law was so vague as to be unconstitutional.

“The fundamental right of the woman to choose whether to bear children follows from the Supreme Court’s and this court’s repeated acknowledgment of a ‘right of privacy’ or ‘liberty’ in matters related to marriage, family, and sex,” Justice Raymond Peters wrote in the opinion.

After the decision was handed down, The Times reported that it was the first time a high court anywhere in the country had ruled on the constitutionality of an abortion statute.

By the time the ruling was issued, lawmakers had amended the state’s law to legalize abortion when a woman’s mental or physical health was at risk or if pregnancy resulted from rape or incest. In its decision, the Supreme Court said it would not rule on the validity of the amended law.

The state attorney general, Thomas C. Lynch, later urged the U.S. Supreme Court to review the California court’s decision striking down the original law, which was enacted in 1850. The Supreme Court declined.

The Belous decision was “a kind of sea change,” said Alicia Gutierrez-Romine, author of “From Back Alley to the Border: Criminal Abortion in California, 1920-1969.” States began seeing challenges of their own abortion restrictions using some of the same legal arguments.

“You begin to see some of these federal cases pop up shortly thereafter,” said Gutierrez-Romine, an assistant professor of history at La Sierra University in Riverside. “It’s a kind of full-circle recognition that these abortion laws are no longer serving their purpose.”

::

The most renowned case came out of Texas, where it was then illegal to have an abortion except by a doctor’s orders to save a woman’s life.

Linda Coffee had been researching and writing a challenge to the state’s abortion laws even before she graduated from the University of Texas School of Law.

In September 1969, while studying which legal arguments failed in previous challenges to abortion restrictions across the country, she came upon the case of People vs. Belous. She immediately got excited. If the fight had succeeded in California, she reasoned, there was a possibility of successfully challenging Texas’ abortion law on the same basis.

Coffee would later refer to People vs. Belous as “the most pertinent case I reviewed.”

“That’s really what started this talk about the right of privacy,” she said in a recent interview.

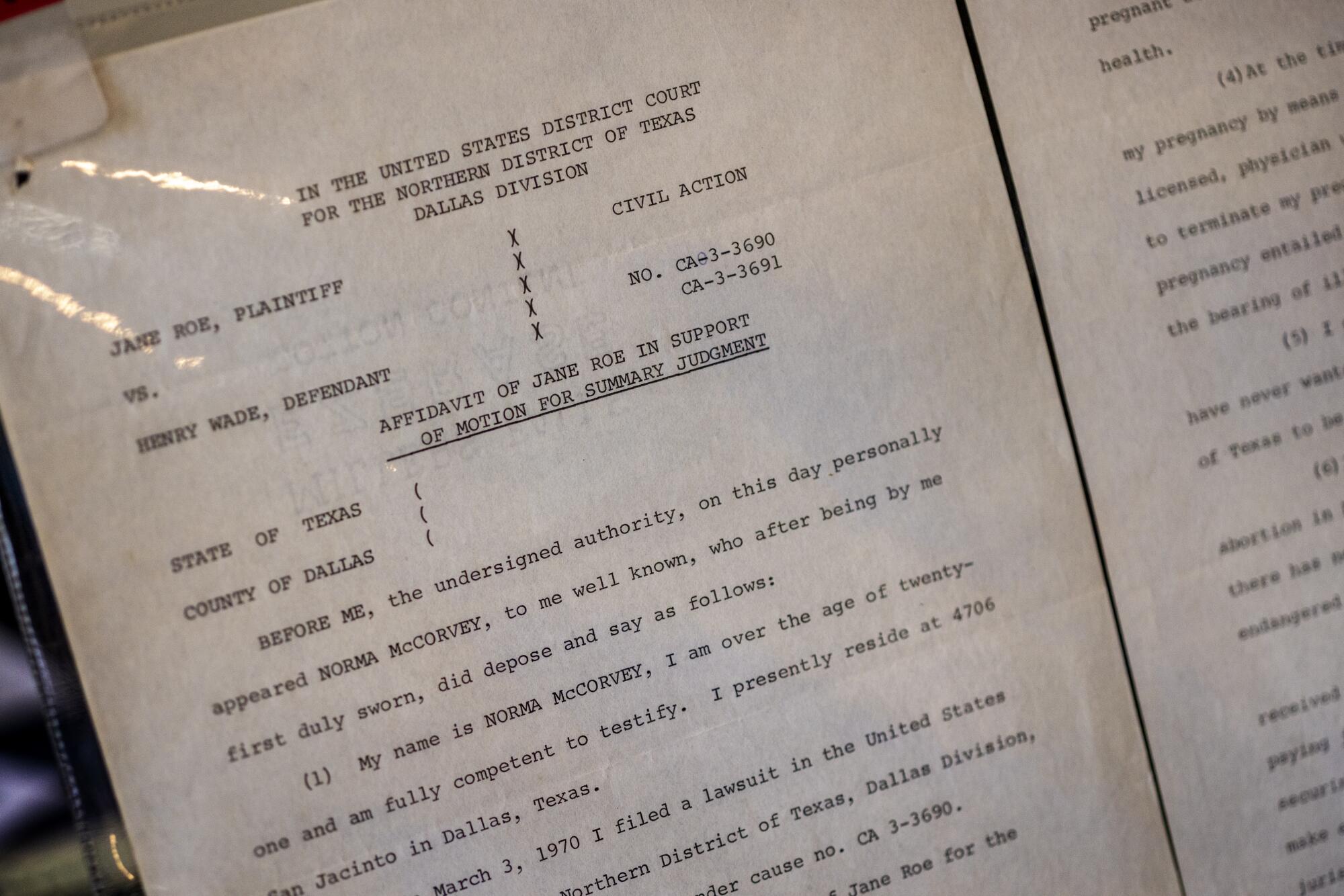

She soon teamed up with Sarah Weddington, an Austin lawyer, to contest the Texas law. They represented Norma McCorvey, who was more than two months pregnant. McCorvey used the alias “Jane Roe.”

The case was brought against Dallas County Dist. Atty. Henry Wade and eventually wound up before the Supreme Court.

“Everybody knew that that’s where the decision would have to be made,” Coffee said.

She recalled going to the Supreme Court and having to take nearly a dozen flights of stairs each time she needed to use the women’s bathroom. It felt, she said, like “an indication they didn’t expect to have very many women arguing.”

In January 1973, the Supreme Court’s 7-2 ruling legalized abortion nationwide. Cited in the decision was People vs. Belous.

::

To his patients, Belous was a steadfast advocate. To Cheryl, he was the man who saved her life.

To Stone, he was her grandfather and the doctor who delivered her. He gave her a “perfect bellybutton” — anyone who sees it says so, Stone blushed. Years later, he gave her birth control.

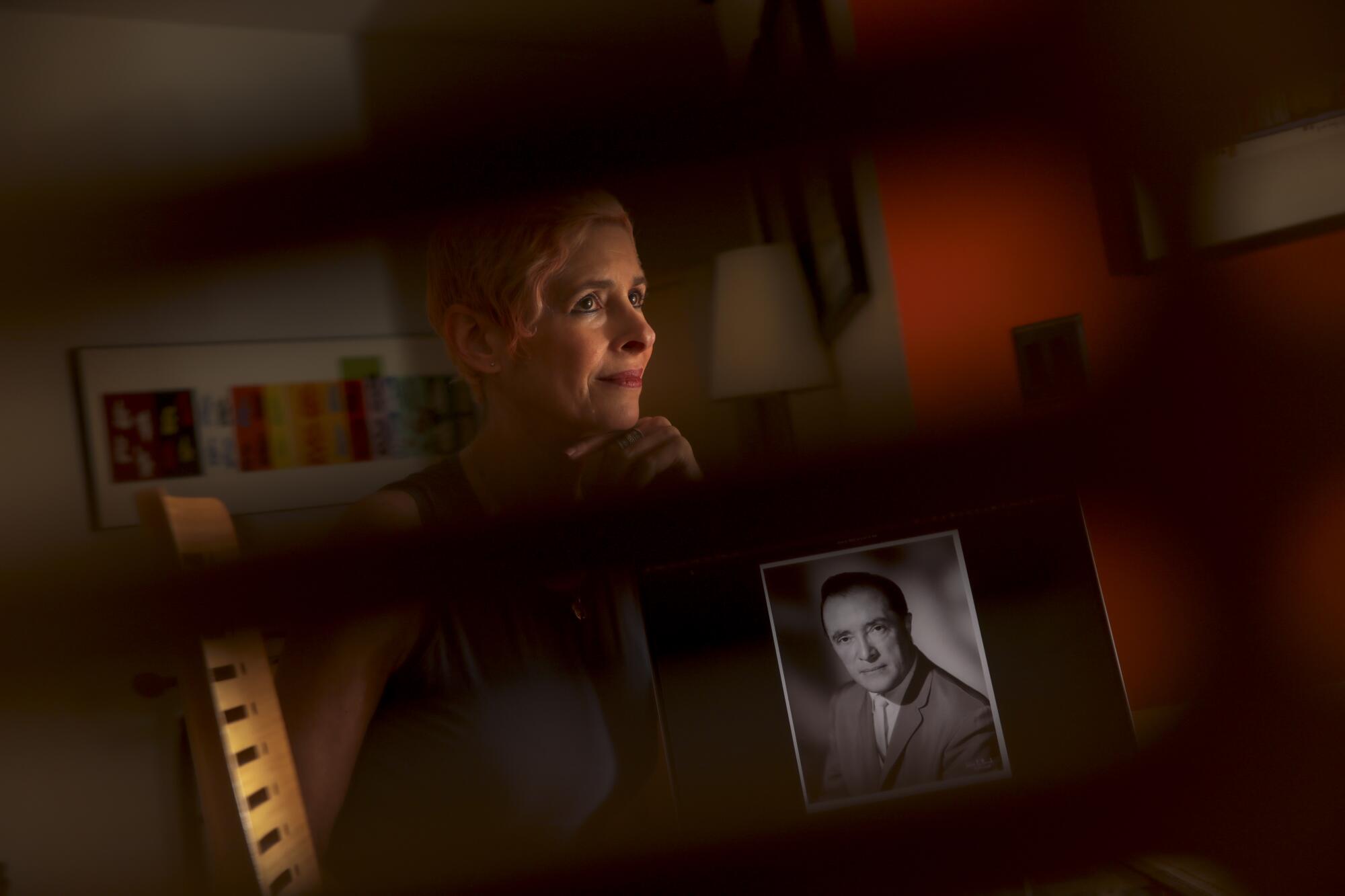

Decades have passed and Stone, now 58, still gets emotional talking about her grandfather.

For much of her young life, she lived across the street from her grandparents’ two-story home. At their house, there was a banister she could slide down and a basement that felt like a secret garden, the floor covered in birth control samples. They were walking distance to Schwab’s Pharmacy and had free soup for life, she joked, as Belous had delivered the babies of nearly every waitress there.

Stone’s grandfather was the one who taught her about pregnancy and delivering babies. He’s the one who talked to her about abortion.

“Even at such a young age, I understood what a coat hanger meant. I understood what Tijuana represented. I knew the phrase ‘back-alley abortion,’” Stone said. “I understood it from the standpoint of life lost, because that decision was not available to so many women.”

But it wasn’t until years later that she realized the toll the abortion-rights crusade had taken on Belous.

Late in his life, her grandfather confided to her that when he sat her down on his lap to ask about going away, he’d had a gun in the back of his closet.

“He felt that he couldn’t not fight. But he couldn’t put his family in that kind of peril,” said Stone, as she wiped away tears. “When I told him that I needed him, that was everything ... that was enough for him, and he stayed.”

After winning his legal battle, Belous retired in 1971. Seven years later, he wrote a letter to the editor of The Times in which he referred to himself as the “leading crusader in the 1960s for legalized abortion.”

“How proud I was of our Supreme Court and our state of California,” he wrote. He went on to slam the Legislature for voting to deny Medi-Cal funds for abortion: “When I read about the cowardly and barbarous act of our Legislature again forcing poor women into the crematoria of abortion mills with all their deadly implications, I was thrown into the deepest depression.”

Belous died in September 1988, the year that Stone married. Obituary headlines touted the 84-year-old as a “Pioneer in abortion issue” and an “Abortion Ruling Figure.” The Desert Sun wrote that the California Supreme Court ruling “opened the door to legalized abortion throughout the nation.”

His granddaughter said she is “happy to be his legacy.”

Stone called the continued battle over abortion “sickening.” She’s the first to admit that she doesn’t have her grandfather’s temperament to stay calm and grounded about it. The greatest emotional upheaval, she said, has been watching “every bit of ground that we’ve gained ... crumble beneath our feet.”

::

Cheryl and Cliff have lived in Bigfork, Mont., since 1993, following in the footsteps of Cheryl’s grandfather who spent much of his life in the state.

A sign planted in a grassy field in town touts, “God’s Ten Commandments.” Red letters on a white cross proclaim, “Christ died for you will you live for him?” Downtown, prayer request forms are inside a wooden box for those in need of intercession.

They have lived through it all together. Cheryl got her start as a substitute teacher, Cliff as a school psychologist. They had their son Casey in 1970 — when they were married, launched in their professional lives and ready for a child. They watched their children and then their grandchildren grow up. (Tyrone went on to become a commercial airline pilot.)

“My husband and I have worked so hard, we’ve done so well in life together as a team,” said Cheryl, her eyes a bright blue behind her wire-framed glasses.

Twice a day, they feed their Appaloosa horses, with names like Glacier Cat and Spotted Wind. Cliff feeds the barn cats; Cheryl one of the wild turkeys she affectionately calls “turkey girl.”

Now that the U.S. Supreme Court has struck down federal protections for abortion, the procedure will remain legal in Montana under the state constitution. But earlier this year, the Montana attorney general asked the state Supreme Court to overturn the 1999 decision that found the state constitution’s right to privacy guarantees a woman’s access to an abortion. The court has yet to rule.

The current conversations around abortion, Cliff said, feel like “a throwback.”

“The United States is going backwards,” he said. “You can’t force people to shift your belief system. ... I’m not going to argue with people about it. My refrain is, if you don’t believe in abortion, don’t have one. But to try to force other people to believe that same way is wrong.”

Cheryl called it “dinosaur thinking.” “The Founding Fathers wanted church and religion out of government, and here we are.”

There’s “positive energy in bringing life into this world sort of on your terms,” she said, “rather than being forced to do it the way the government is prescribing.”

Besides, Cheryl added, women would continue to have abortions, “whether they’re legal or illegal.”

The same way she did 56 years ago.

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.