Recent report on L.A. County hate crime numbers is a reminder of when we didn’t even count them

- Share via

You could plausibly take the point of view that much of the history of the 20th century is one long chain of hate crimes.

Still, no one evidently thought to put together the words “hate” and “crime” in any significant way until the 1980s — not even back in 1968, when President Lyndon Johnson signed a monumental civil rights act that criminalized force or the threat of it against anyone because of race, creed, color, faith or national origin.

In 1990, President George H.W. Bush signed the Hate Crime Statistics Act, requiring the attorney general to publish an annual report on hate crimes. States and cities give these data to the FBI voluntarily, so the results are a puzzling patchwork: In 2020, five dozen police departments in cities with more than 100,000 people reported no hate crimes at all.

Since 1990, myriad iterations of laws, at the national and state levels, forthrightly use the phrase “hate crime,” among them the federal Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act of 2009.

Los Angeles’ 2021 tally, the most recent available, makes for dismal reading: yet more hate crimes against Black, Jewish, LGBTQ, Asian and Latino people.

But at least there are numbers, and the numbers represent something, because for decades there was no systematic reporting or accounting of these offenses as hate crimes. You just know they happened, but it makes for elusive and frustrating research.

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

What can be calculated, in Los Angeles as anywhere else, is how deeply hate offenses were institutionalized — committed by organizations and even by official powers that, in the here and now, are tasked to punish them.

Among the earliest: groups of “Rangers,” Southern California horsemen assembled nominally to hunt down Mexican “bandidos” but who, as a vigilance committee, became judge, jury and even executioner themselves. Gold-hunting ’49ers arriving from U.S. points east found native Californios and other Latinos already working the gold fields and hounded them out, to the point of murdering them. A few Californios, aggrieved by that and the power grab resulting from statehood, took to banditry. There were plenty of Anglo criminals plundering the place, too — the legendary Irish-born crime boss Jack Powers among them. But more often it was Californios who were pursued and even lynched. In one instance, Rangers from El Monte — more will be heard of El Monte soon — killed some of their prisoners on no more authority than their own.

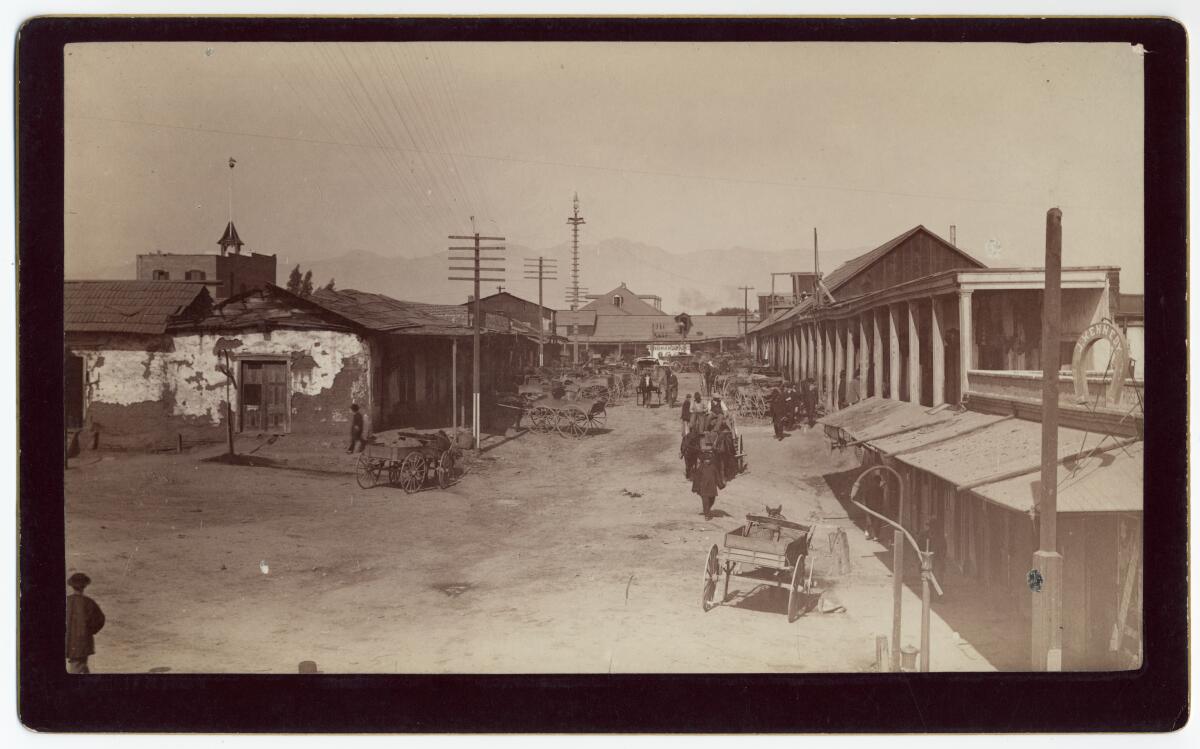

In the 1850s, the town of Los Angeles, with about 5,000 people, was averaging a murder a day. (For context, the city today has about 4 million residents and has averaged about one homicide a day since 2020, which we consider a worrying rise compared with decades prior.) The historian Leonard Pitt wrote that conditions in L.A. in that decade amounted to nothing less than a “race war” against both Californios and native Americans.

Native Americans had been “liberated” when the missions were secularized in the 1830s — but then dispossessed into a form of slavery. Hired for menial jobs, they were sometimes paid in liquor, or they bought liquor. Then, after they got drunk and disorderly, the marshals rounded them up and, come Monday morning, auctioned them off to the ranchers and growers who posted their bail in exchange for their work.

Horace Bell, an Anglo pioneer who made note of his own sympathies toward Californios and native Americans, chronicled that “Los Angeles had its slave mart … only the slave at Los Angeles was sold 52 times a year as long as he lived, which did not generally exceed one, two or three years.”

This reckless, lawless Los Angeles finally registered with the greater world in 1871, with the Chinese massacre. The New York Times wrote: “One of the most horrible tragedies that ever disgraced any civilized community … Los Angeles, although boasting of being the city of the queen of the angels, is cursed” as a “hotbed of crime and depravity” — not the first time nor far from the last that that name has painted on the city’s back a target and irony.

It began as a battle between two Chinese tongs over the abduction of a young woman — of whom there were few — and spilled over into the streets of the small “Calle de los Negros,” where most of L.A.’s Chinese lived and worked.

When a lawman and a civilian were shot in the melee, a crowd of whites and Latinos gathered and became a mob, attacking the Chinese who had holed up in an adobe building and opening fire. A few Chinese were taken to safety, but in the end, at least 18 had been hanged by the mob, and some had been shot and stabbed too. Eight men were convicted of manslaughter in the savagery and sentenced to San Quentin, but the convictions were overturned.

It’s too much of a stretch to say the massacre scared L.A. “straight” when it came to racial violence. But boom times lay just ahead, and the Yankee entrepreneurs who wanted to make themselves rich had to make L.A. into a respectable place, or at least a quiet one.

So this shameful thing was expunged from the city’s storytelling. Not until 2001 was there a monument to mark the event.

In 2021, UC Davis law professor Gabriel Chin told The Times, “This was an ethnic cleansing. And it was successful.”

Chinese residents lost their lawsuit for damages, but the year after the massacre, most Chinese laundrymen refused to pay their city business license fees.

“Them: Covenant” on Amazon Prime is a reminder of the all-too-common housing covenants that restricted who could buy homes in certain neighborhoods in Compton, around Southern California and elsewhere. Determined Black people over the decades fought for their rights to live where they pleased.

To now skip ahead about 50 years is not to say that those decades were free of hate crimes — only that their official perpetrators were better able to cloak themselves in the garb of authority.

In the 1920s, the nationwide revival of the Ku Klux Klan reached Los Angeles, where sympathy for the Confederacy took root during the Civil War. In 1908, when the racist Reconstruction novel “The Clansman” toured here as a stage play, a petition from self-described “respectable, God-fearing and peace-loving” Black Angelenos asked the mayor to ban the production, as mayors elsewhere had. Seven years later, before the movie version that was eventually renamed “The Birth of a Nation” could open here, the city’s board of censors ordered that four unspecified scenes be removed.

The early 1920s were the apogee of the revived Klan in Southern California. The “invisible empire,” as the KKK called itself, was taking over the very visible government.

In 1924 in Anaheim, where Latino schoolchildren were already formally segregated from Anglos, the Klan had four of five City Council seats and most of the police department. Anaheim billed itself as a model California Klan city. Robed Klansmen sometimes stopped locals to question them and stood at intersections directing traffic.

Crosses were burned in Brea, Fullerton, South Santa Ana. Klansmen raided bootlegger operations, then had the gall to bill cities $11,200 for their services. A school board member in Santa Ana told school principals that all the teachers should join the KKK.

A raid in 1922 on an Inglewood Basque family whom the KKK suspected of bootlegging was a shambolic mess. A city marshal was alerted to the raid by a Japanese neighbor; the Klan was unsparing toward Japanese people too. Two of the Basque men were beaten and kidnapped but rescued; the only fatality was when the marshal shot a KKK member, who turned out to be an Inglewood constable.

Inglewood locals carrying pistols turned up at the inquest to side with the Klan. The state KKK leader argued that his men were just trying to clean up the town. The district attorney, the state and the feds began investigating; 150 witnesses were summoned — some of them community leaders who professed total ignorance of any Klan doings. The investigation unearthed the fact that both the L.A. County sheriff, William Traeger, and the LAPD chief, Louis D. Oaks, were Klan members. Both men said they’d resigned from the KKK. In all, 37 men were indicted — and all 37 were acquitted.

Official and unofficial “sundown towns” dotted L.A. County: Culver City, Burbank, many South Bay towns and Glendale, where the KKK flourished for a time and a branch of the American Nazi party was founded by its leader, George Lincoln Rockwell. The cities and sometimes their police made it clear by harassment and even with posted signs that people of color were well advised to leave town before sundown.

In 1923, El Monte’s 300 or so Klan members split with the state organization over charter disputes, along with members from Azusa, Montebello, Pasadena, Covina and the community of Belvedere.

In a 1975 reminiscence to The Times, the late John Schutz, a Los Angeles native and head of USC’s history department, recounted seeing huge KKK assemblies on Telegraph Road in East L.A., with Klansmen lining up their cars in rows to aim their headlight beams toward the speakers’ podium: “I can still see those white-hooded people.”

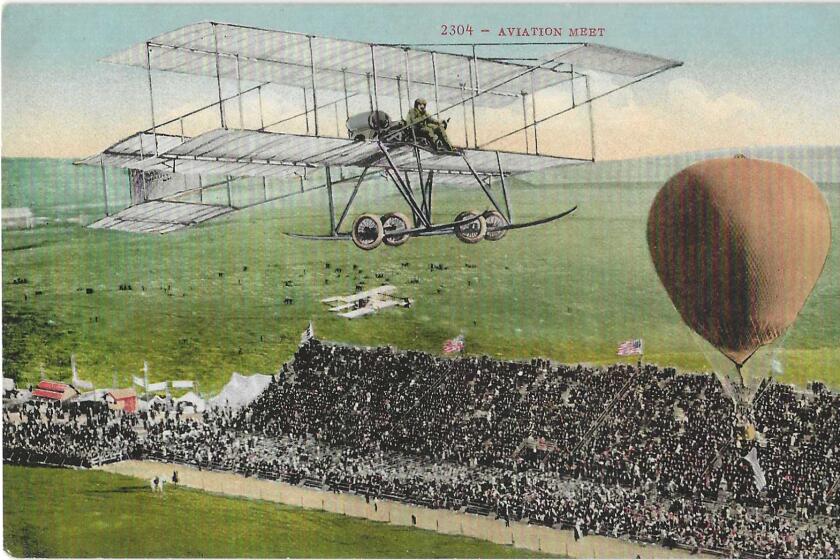

A mere six years after the Wright brothers’ famous first flight, Los Angeles hosted the United States’ first significant air show. In addition to being a spectacle, it solidified Southern California’s place as an aerospace hub.

Through the Depression and onward, the Klan and the hate groups that splintered from it and re-formed under other names were not a spent force.

The USC history professor Steven J. Ross wrote the 2017 Pulitzer-finalist book “Hitler in Los Angeles: How Jews Foiled Nazi Plots Against Hollywood and America.” For a new book in the works, “The Secret War Against Hate: American Resistance to White Supremacy After 1945,” he unearthed some startling things.

The popular and colorful L.A. County Sheriff Eugene Biscailuz, who was of French Basque descent and was born in Boyle Heights, had organized the new California Highway Patrol and brought new methods and technology to the Sheriff’s Department. But right after the Pearl Harbor attack, Ross told me, Biscailuz “struck a deal with the local Klan: guns for votes.

“The sheriff promised to deputize Klansmen as an emergency sheriff’s unit. That allowed them to create an all-KKK unit of the sheriff’s auxiliary that could purchase weapons and ammunition as part of the sheriff’s department,” he said.

James Harvey, the California KKK’s “Imperial Knight-Hawk” — oh, those titles — pledged that the Klan stood against President Roosevelt’s policies and would keep up its activities “regardless of the war.”

The Times has reported for decades on racist elements within the Sheriff’s Department.

“The Sheriff’s Department claims it’s always just a few rotten apples,” Ross said. “My argument is that that barrel has been rotten forever. Biscailuz was making all kinds of deals, [like] with an anti-Semitic racist group that was founded during the war. He was determined to hold office at any cost.”

The Klan did not act alone here. The Silver Shirts, an American-grown fascist group, collected members in L.A., Baldwin Park, Huntington Park and beyond but rather fell apart when the U.S. entered World War II. Pro-Nazi groups stayed on message even during the war, when the Bund, an Americanized version of Hitler’s party, staged rallies in a La Crescenta park.

With Japanese people corralled in camps, the “troublemakers” in police crosshairs were often Latinos. Young Latino men not in uniform were targets for contempt, as the Zoot Suit Riots of June 1943 put on violent display.

The zoot suit — a dramatic style worn by Black celebrities like Cab Calloway and adopted by young Black, Latino, and Filipino men — was an exaggerated silhouette that took a lot of fabric to make, and fabric was rationed during World War II.

But that was just the excuse for 10 or so days when soldiers and sailors hit the L.A. streets, beat up zoot suiters and stripped off their clothes.

The murder of Jose Diaz in 1942 led to two landmark injustices against Mexican Americans. So why has history forgotten him?

The Times wrote more than 50 years later that “exactly what triggered the vigilante action was never clear. Some trace it to earlier assaults on military personnel, allegedly carried out by Mexican American gang members who called themselves pachucos. Others said Los Angeles police precipitated the attacks to divert attention from a fellow officer who was about to go on trial.”

For several nights, the servicemen, mostly sailors, went looking for the zoot suiters, and at least once going after a Latino man who was not wearing a zoot suit. Eventually, the Latinos regrouped and organized counterattacks. The police did virtually nothing to stop the beatings. At last, the military confined its servicemen to base.

The Times crowed, “Those gamin dandies, the zoot suiters, have learned a great moral lesson from servicemen.”

The year before, 1942, the “Sleepy Lagoon” murder of a young Latino by other Latinos had given law enforcement and the local press the opening to lay into “Mexican” crime and delinquency, with raids and indictments. Biscailuz released a report on “Mexican crime” and offered up his own far-fetched idea that zoot suiters had made common cause with the Japanese to stir up trouble for authorities in order to hurt the war effort. As Kevin Allen Leonard wrote in his book “Years of Hope, Days of Fear,” Biscailuz theorized that “the Japanese left instructions with these hoodlums before they were forced to leave their homes.”

Today we expect much, much better of our elected and unelected law enforcement officials and are much, much better at holding them to account when they fail.

L.A. County voters in November appear to have reinforced that message. They dumped a polarizing sheriff and replaced him with East L.A.-born Robert Luna, who led the Long Beach Police Department and committed himself to restoring trust in the Sheriff’s Department. In the city of Los Angeles, meanwhile, it is Karen Bass, the first woman and second Black person to serve as mayor, who is evaluating whether LAPD Chief Michel Moore should get another term.

Does much remain to do? In a word: duh. But the bad old days of top cops openly dealing with and joining the Klan remain, without question, bad, but thankfully, ideally, old.

Los Angeles is a big, complicated place. Patt Morrison explaining how it works, its history and its culture in Explaining L.A. on latimes.com.

More to Read

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.