How a 1910 air show launched L.A.’s rise to aerospace capital

- Share via

Oh, the poetry and the wonder of manned flight! The dream of figures of myth and history, of Icarus and Leonardo da Vinci!

Yeah, yeah. In 1910, Los Angeles was in it for the dough. And the PR.

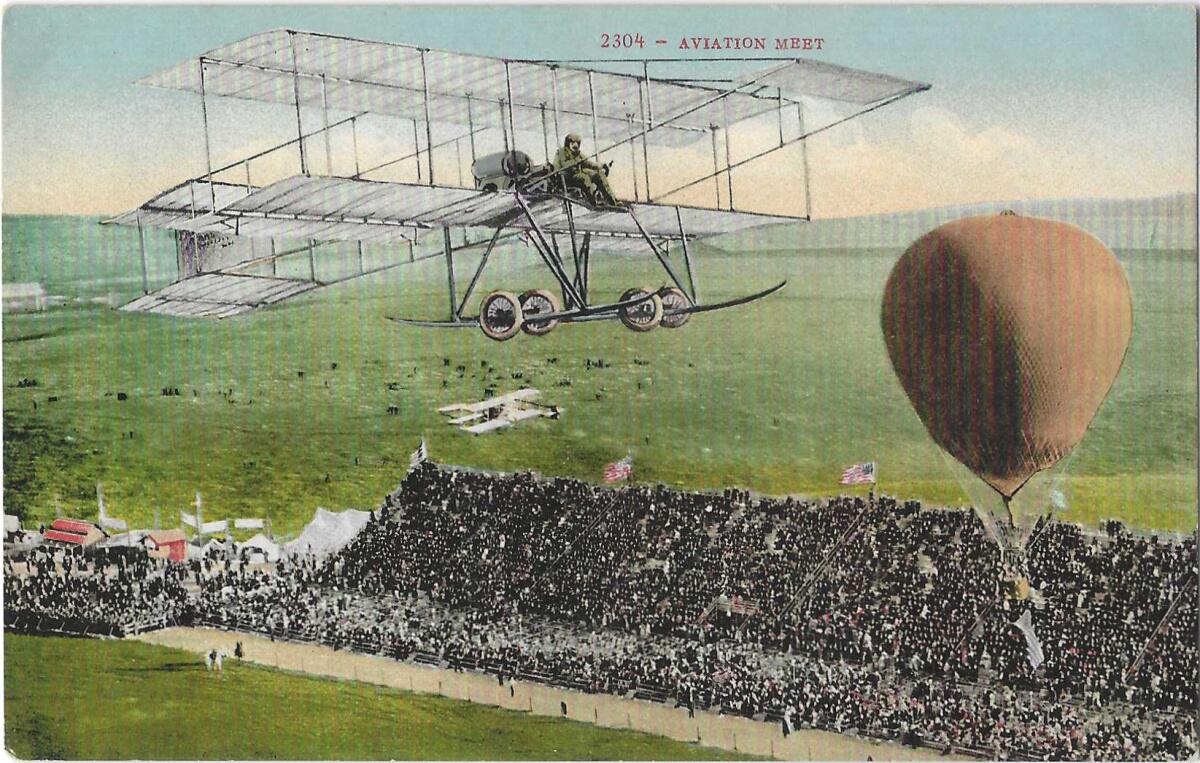

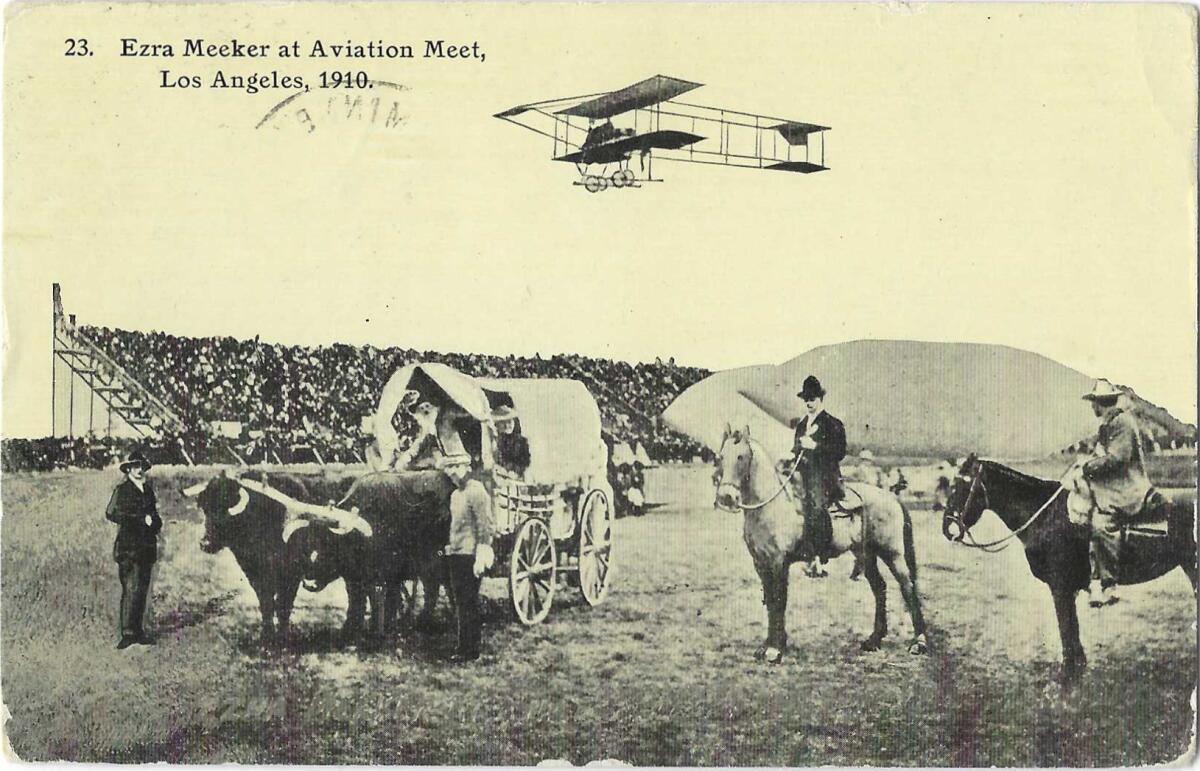

The United States’ first significant air show was 10 days of thrilling feats of aviation on and above the bare hilltop and fields of the old Spanish grant lands of the Dominguez family, which welcomed the air meet after it turned out that the entire East Coast was too cold — duh, January — and the other possible local site, Santa Anita-Arcadia, had too many big trees. And Dominguez had the advantage of a hilltop which let promoters limit attendance to ticket-holders.

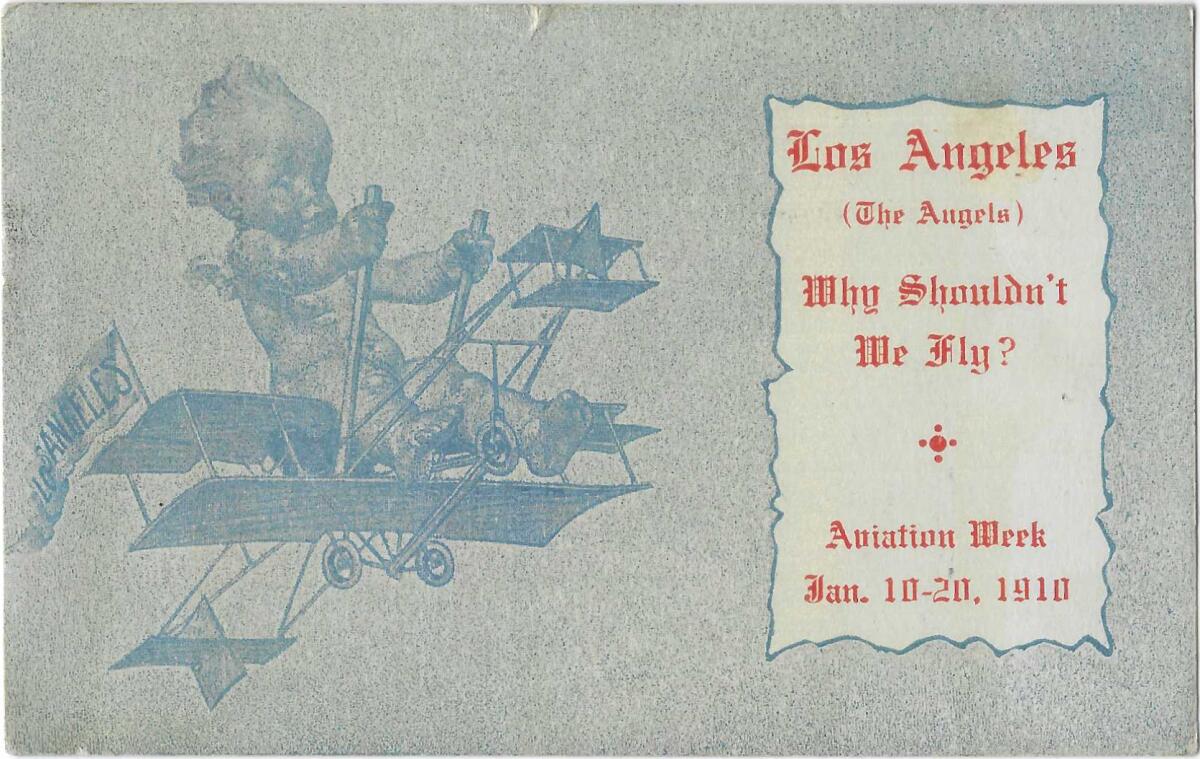

In 1910, when Los Angeles County’s population was half a million people, at least a quarter-million people went to the air show, and probably a lot more than that. Special train cars were laid on for visitors from San Diego and San Francisco. Hotels offered package deals with rides to the makeshift airfield. The promoters commissioned brochures and posters, among them probably the most glorious graphic image ever made of Los Angeles.

The 10 days of derring-do acrobatics and races by celebrity plane and dirigible pilots did far more than even Los Angeles boosters might have dreamed. The air meet put Los Angeles on the map as a fine place for flying and for creating and testing planes. In the century to come, L.A. would become the core and the capital of aerospace, defense industries, commercial aviation and amateur flying, a magnet as well for untold billions of dollars that lofted L.A.’s fortunes like the hot air in a balloon.

Thus, beyond the air meet’s ticket sales, the leading-edge pioneers of aviation came here — watching, learning, dreaming up the next breakthrough in flying technology.

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Barely six years after their first flight, the Wright brothers reportedly showed up at the meet too — and stayed on the ground, with their lawyer, alert for any fliers who they thought were stealing the brothers’ patented designs. The Times indirectly blamed the brothers’ looming presence for a crash that broke a wing on a Bleriot model plane. Their injunction against the plane had prompted mechanics to remove a special wing-warping device, leaving aviators with only tail control.

That made me think of why California was desirable in so many aspects to moviemakers too — weather, topography and that comforting 3,000 miles between here and Thomas Edison’s own vigilant lawyers policing Edison’s patents on moviemaking equipment.

The year 1910 gave L.A. a crystal-ball look into its future. Not quite two weeks after the air meet ended, a silent movie began shooting. By then, the Edendale neighborhood was already a film factory, but this was the first movie made completely in Hollywood. The 17-minute film (991 feet of filmstock, as it was calculated) “In Old California: A Romance of the Spanish Dominion” was released two months after the air meet. Hollywood, like Southern California aviation, would never come back to earth.

(The year’s third seminal event, the October bombing of The Times by union members — the paper had led the battle against labor unions — set back the burgeoning labor movement, and set in concrete for years to come the city’s vehement business crusade against organized labor as the handiwork of the forces of wickedness.)

The No. 2 man at the muscular Merchants and Manufacturers Assn., Felix J. Zeehandelaar, can be forgiven for being clueless about the imminent global renown of moviemaking when he wrote in The Times, “I can truthfully say that nothing has ever taken place in this city that will attract so much attention or give Los Angeles so much widespread publicity as the flights that will take place next week.”

The association — M&M, the locals called it — had helped to kick the meet into gear with a pledge, as had the rail magnate Henry Huntington, who did good and did well. The multitudes paid 30 or 35 cents each for a round trip aboard his special trolley cars to get to the aviation meet.

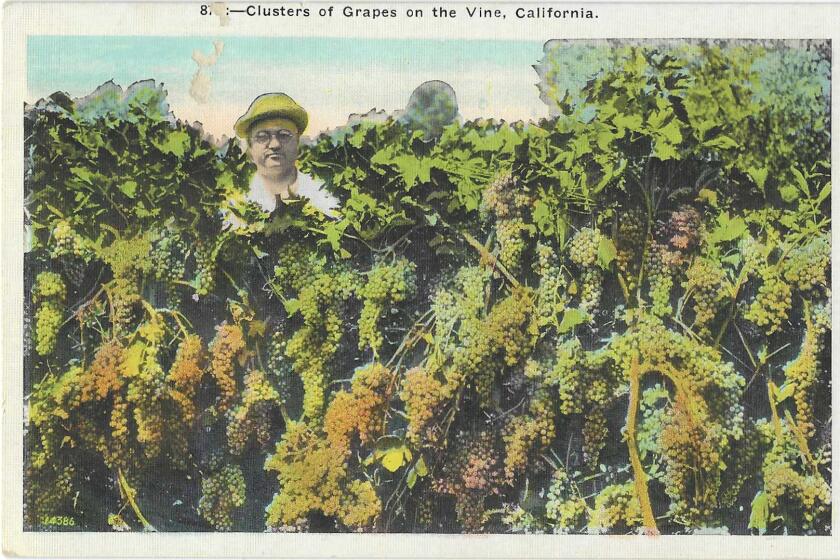

Next time you raise a glass of California wine, remember the time when Los Angeles, not Northern California, was the state’s major wine region.

Unusual for this churchgoing town, a Sunday day of festivities was added so that six-day-a-week working Angelenos could visit the meet too.

To get to their seats in the grandstands, visitors walked past tents and concession booths: “wienie” vendors, coffee sellers hawking overpriced 10-cent cups, first-aid tents and carnivalesque attractions like the conjoined twins Cora and Etta; for the occasion, they were called the “Human Biplane.”

An enterprising Harvard grad named Le Valle Smith pocketed more than $700 hauling water to Dominguez and selling it for 5 cents a cup to spectators, and 10 cents a gallon to concessionaires.

Promoters and advertisers whipped locals into a frenzy of anticipation — if you miss it, you’ll regret it. Women wore hats shaped like airplanes, and pinned bunches of violets to their coats and fur muffs. Men’s tailors advertised nifty new coats for the event, department stores ran “aviation sales” on, perplexingly, lace and coral dinner rings. With your 25-cent minimum purchase at the Broadway department store, you’d get a free copy of the sheet music for “Up in My Flying Machine.”

Berlin Dye Works offered specials to clean the clothes you’d dirtied out there at the air meet. The Times published a helpful aviation glossary of terms: lateral stability, ornithopter, gliding speed, wing warping.

When you realize that few people in the country had even seen an airplane — it was barely six years since the Wright brothers made it aloft for all of 12 seconds — “aviation week” was an astonishment and a revelation: a sky full of fixed-wing flying machines and cloud-like puffy dirigibles, every day a new and daring performance.

One day, as The Times wrote, “Every war office in the world was watching” as a man dropped bags of sand at a white paper target on the ground. It was no mere stunt: “It was the raising of the curtain on the war game of tomorrow.”

On another day, the paper flaunted the promise of “Aerial Queen Will Hover Above City” — that was Ruth Neely, the first woman to pilot a dirigible. She was shown in a faraway profile that made her look rather like Margaret Hamilton as the bicycling Miss Gulch in “The Wizard of Oz.” Up the road in Huntington Park, hot air balloons floated like jellyfish above the landscape.

There were injuries, but evidently no deaths. Los Angeles teacher James Zerbe’s homemade plane, with five pairs of wings stacked like a layer cake, collapsed on its first try. Mounted sheriff’s deputies galloped onto the field — and right past the unhurt Zerbe, to where a young aviator named Edgar Smith had been whacked in the head by his own plane’s propeller.

The air meet was advertised as “international,” claiming the standing of the world’s first great air meet five months earlier in Reims, France. That city had been sending people airborne for centuries; its principal product was Champagne.

California was terra incognita to the tight fraternity of fliers on the East Coast and in Europe. Of the 43 flying machines that were officially entered to compete, only 16 of them showed up to take part.

The most celebrated of the French fliers was Louis Paulhan, who eventually won a full purse of prize money at Dominguez for the longest and highest flights — one hour, 49 minutes; and 4,164 feet. He arrived with his entourage, which included his black poodle, Escapade, and, in a brief kerfuffle, a ticket-taker thought Paulhan was a gate-crasher and demanded that he show his ticket. (The meet organizers, intent on making money, were murder on gate-crashers.) A local Frenchman — and L.A. had many of them — indignantly came to Paulhan’s assistance and the show went on.

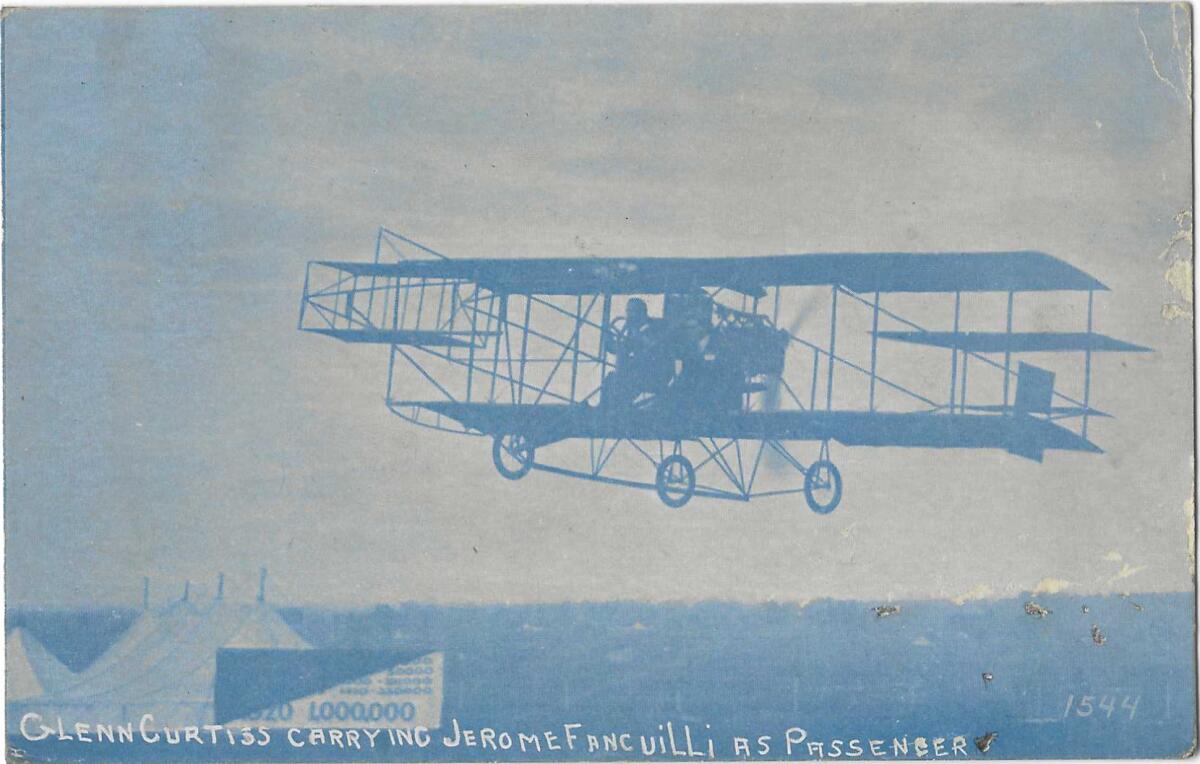

The local hero was the nation’s hero pilot, the aviation pioneer Glenn Curtiss, who had won the overall speed record at Reims. He won cash prizes and set two records at Dominguez, one of them for quickest takeoff in his monoplane — 6.4 seconds.

Far and away, most of the crowd had come to see their first airplanes, to gasp and to thrill. A few were taking mental notes. Glenn Martin was another future aviation industry pioneer. He’d get his pilot’s license the next year, and four years after that, would promote flying in the movies, and take silent star Mary Pickford for a flight over Griffith Park as her mother stood on the ground frantically motioning Martin to come back down.

A man who should have had an honored seat among the VIPs was Thaddeus Lowe. His advanced technical innovations with balloon reconnaissance prompted President Lincoln to make him “chief aeronaut” of the Union army’s balloon corps. He made and lost a fortune with his Mt. Lowe railway above Pasadena. At his side at the air meet was his 8-year-old granddaughter Florence, whose fame came to outstrip his. As Pancho Barnes, she made a stunt-pilot reputation for herself and ran the Happy Bottom Riding Club, the hangout beloved of early test pilots at the desert site that became Edwards Air Force Base.

Who is Griffith Park named for? What about Vasquez Rocks? The Broad? Mt. Lowe? Here are the namesakes of L.A.’s best-known landmarks.

A young William Boeing showed up day after day, buttonholing every pilot he could for a skyride. Only Paulhan agreed, but told Boeing that he had to wait his turn behind the celebrities, like William Randolph Hearst, one of the meet sponsors, whose Los Angeles Examiner tethered a balloon in everyone’s line of sight on the fairgrounds, encircled with the words “ALL IN THE EXAMINER.”

At last, Paulhan promised him a ride the following day, but when Boeing showed up, eager for his flight, Paulhan had already packed up and left — maybe to avoid the Wright brothers’ lawyer — and Boeing went back to Seattle. Perhaps if he’d gotten that ride, Boeing would today be a Southern California aircraft company.

The weather obliged with 10 Chamber of Commerce days of mellow 50s and 60s daytime temperatures, and notched 72 on the last day of the meet. The young world of aviation came away thinking that L.A. — with its basin of wide, flat places and equable weather — was indeed the place for aviation’s future.

And “air-minded” Los Angeles thereafter never looked down — or back.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

More to Read

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.