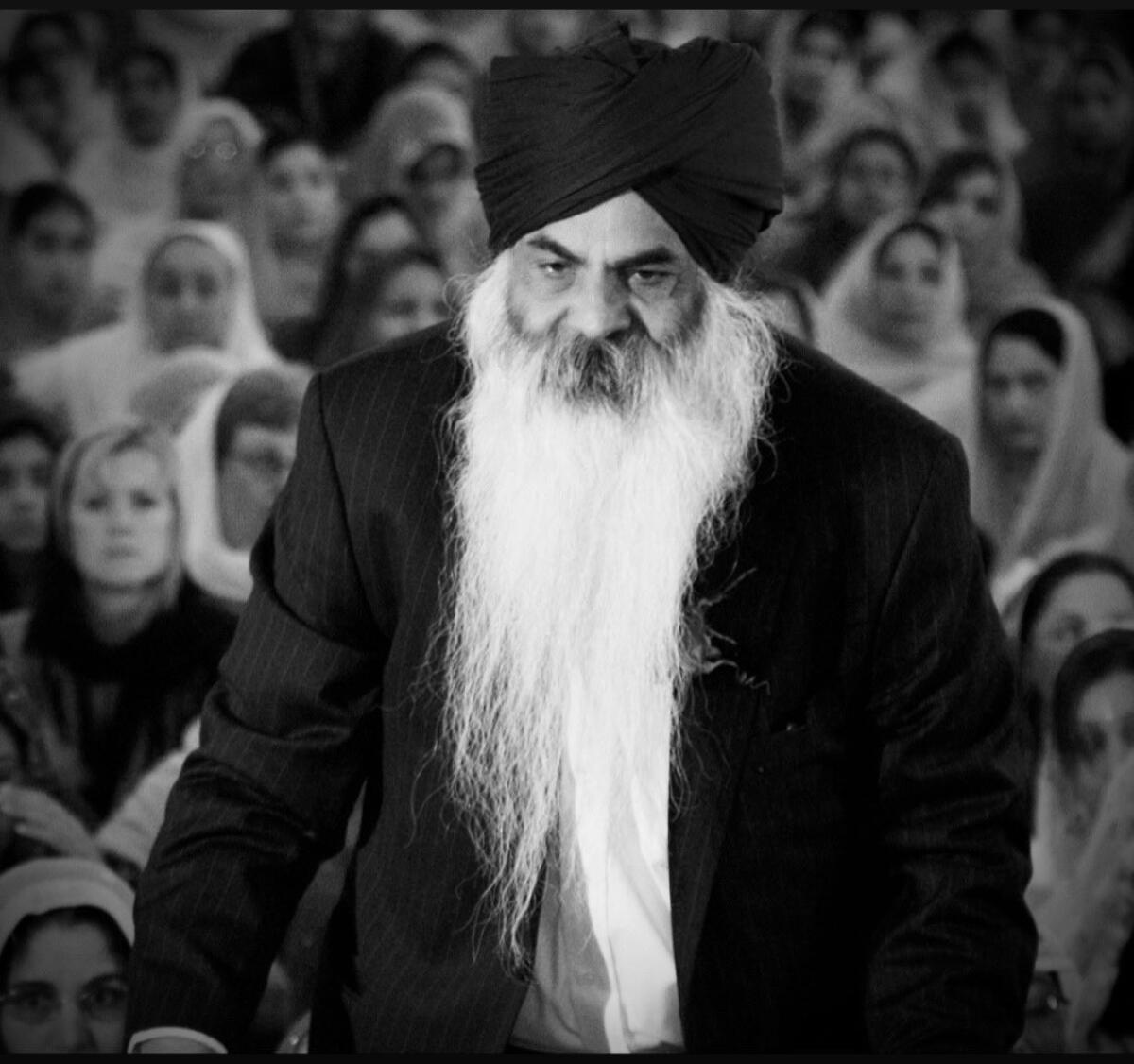

Didar Singh Bains, ‘Peach King’ who built Northern California’s Sikh community, dies

- Share via

In 1980, Didar Singh Bains pitched a plan for what he hoped would be an annual Sikh parade in his hometown of Yuba City, Calif.

But his peers, in a town of 19,000 about 40 miles north of Sacramento, pushed back, fearing violence and unrest.

“Some thought he was crazy,” recalled Karm Bains, Didar Bain’s son and a Sutter County supervisor, in a 2018 interview with NBC News. “People are going to throw rocks.”

But Didar Bains thought differently.

“He said it’s important for us to tell the people who we are,” said Karm Bains. “We are fellow Americans, law-abiding citizens, and we want everything you want for your kids.”

The annual celebration during the first weekend of November now draws some 100,000 Sikhs and others from across the country.

A farmer once deemed the “Peach King” and one of the most prominent American Sikh leaders, Didar Bains died Sept. 13 in Yuba City. He was 84.

Born in a small farming village in the Punjab region of India in 1938, Bains came to the U.S. in 1958 with $8 to his name, following his father who had left for America when Didar was 10, according to a tribute written by his daughter, Diljit Bains, in UC Davis’ Pioneering Punjabis Digital Archive.

From Imperial Valley to Yuba City, Didar Bains worked his way up the state and up the ladder. He eventually settled in Sutter County, with its topography and rivers reminding him of Punjab (Punjab translates to “Land of Five Waters”), Karm Bains said.

Early Saturday morning in northwest Fresno, a 68-year-old farmhand waited curbside for his ride to work pruning grapevines at nearby vineyards.

In 1962, while sending money to his family back in India, Bains also saved up enough to buy a 10-acre parcel in the south side of town. He soon leaned into growing peaches.

Peaches can be notoriously difficult to grow, Bains said. Just two days of frost in April wiped out half the crop this year, he said.

Pruning, thinning and harvesting peaches must be done within a very tight time frame, Karm Bains said. Harvesting has to be done within a window as short as three days.

But Didar Bains had a knack of finding good soil. Combined with his work ethic and leadership skills, his farm grew to hundreds of workers. By 1978, he had become the largest independent peach farmer in California, and perhaps the world, earning him the “Peach King” moniker.

Bains also expanded and diversified his farm, growing cranberries, raspberries and other crops in 13 counties throughout California, as well as Washington, Florida, British Columbia and India. His farm was the second-largest grower of cranberries for Ocean Spray, Diljit Bains wrote.

Kash Gill, Didar Bains’ nephew who became the city’s first Sikh mayor in 2009, recalled his uncle jumping in a tractor at 4:30 a.m. and staying in the orchards until 8:30 at night.

“He said, ‘This is a way I can see every one of my trees,’” Gill said. “He would drive the tractor, so he himself can see firsthand what type of crop he has.”

As Bains’ business grew, he also assumed the role of a community leader. He always emphasized three tenets of Sikhism: living an honest life, thanking God and sharing with those in need.

His farms employed hundreds of workers, many of them Sikh immigrants getting their first job in the U.S. Many of those workers had fled India after 1984, when thousands of Sikhs were massacred in three days of violence following the assassination of Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, who was killed by two Sikh bodyguards.

As a child, Gill would spend nights and weekends at his uncle’s house. In the middle of the night, Gill recalled, Bains would get calls from Sikh immigrants who had been detained after coming to the country illegally and had one free phone call to make.

“When they came to America,” Gill said, “there were only two things they needed to know: Didar Bains and Yuba City.”

)

Bains also helped hundreds of his own family members, giving them housing, jobs and even land.

He became the youngest president of the Stockton Gurdwara Sikh temple in 1965. He raised funds to build a Sikh temple in Yuba City in the 1960s, and founded the World Sikh Organization in 1984 to advocate for the community. He donated millions to help build Sikh temples worldwide, and thousands more to help a Wisconsin police officer recover from a mass shooting at a Sikh temple in 2012.

When American Sikhs were repeatedly targeted after the Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks by people who perceived them as Muslim, Bains and other Sikh leaders organized a meeting with President George W. Bush.

When Gill lost his city council bid in 2004 by a small margin, Bains told him: “Try again.” Gill eventually won a council seat in 2006 and became mayor three years later.

“I could just see a big glow,” Gill recalled watching Bains at Gill’s swearing-in ceremony as a mayor.

In 2014, Gov. Jerry Brown honored Bains at the Sikh Temple of Sacramento.

“Didar’s younger than me,” Brown told the crowd, according to the Sacramento Bee. “The reason I look younger is because I don’t work as hard as he does.”

In Yuba City, Bains’ legacy is everywhere, even at the Walmart and Home Depot stores that he helped bring to the city. He helped the city grow as well, especially in its western and northern ends, said Dave Shaw, the city’s current mayor. Tens of thousands of American Sikhs now live in the city and surrounding county.

The city earlier this year celebrated the groundbreaking of a park named after Didar Bains — whose first name translates to “visionary” in Punjabi.

“He had a vision and a mind-set of where he wanted the people to be,” Karm Bains said. “I hope this is not the end of an era. Hopefully, it’s just a passing of the torch for the next generation to come.”

Didar Bains is survived by his wife of 58 years, Santi Bains; sons Ajit and Karm; daughter Diljit; brothers Dilbag and Jaswant Bains; and sisters Gurmeet Gill, Resham Nagra and Surinder Dale.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.