- Share via

STOCKTON — This farming city in the Central Valley has made headlines for its financial struggles and its annual asparagus festival. But thousands of miles away in India, it is a symbol of terrorism.

To hear the Hindu-dominated media and government tell it, militants funded by the Sikh diaspora will stop at nothing to take over Punjab — the only Indian state where Sikhs are a majority — and turn it into a country of their own called Khalistan.

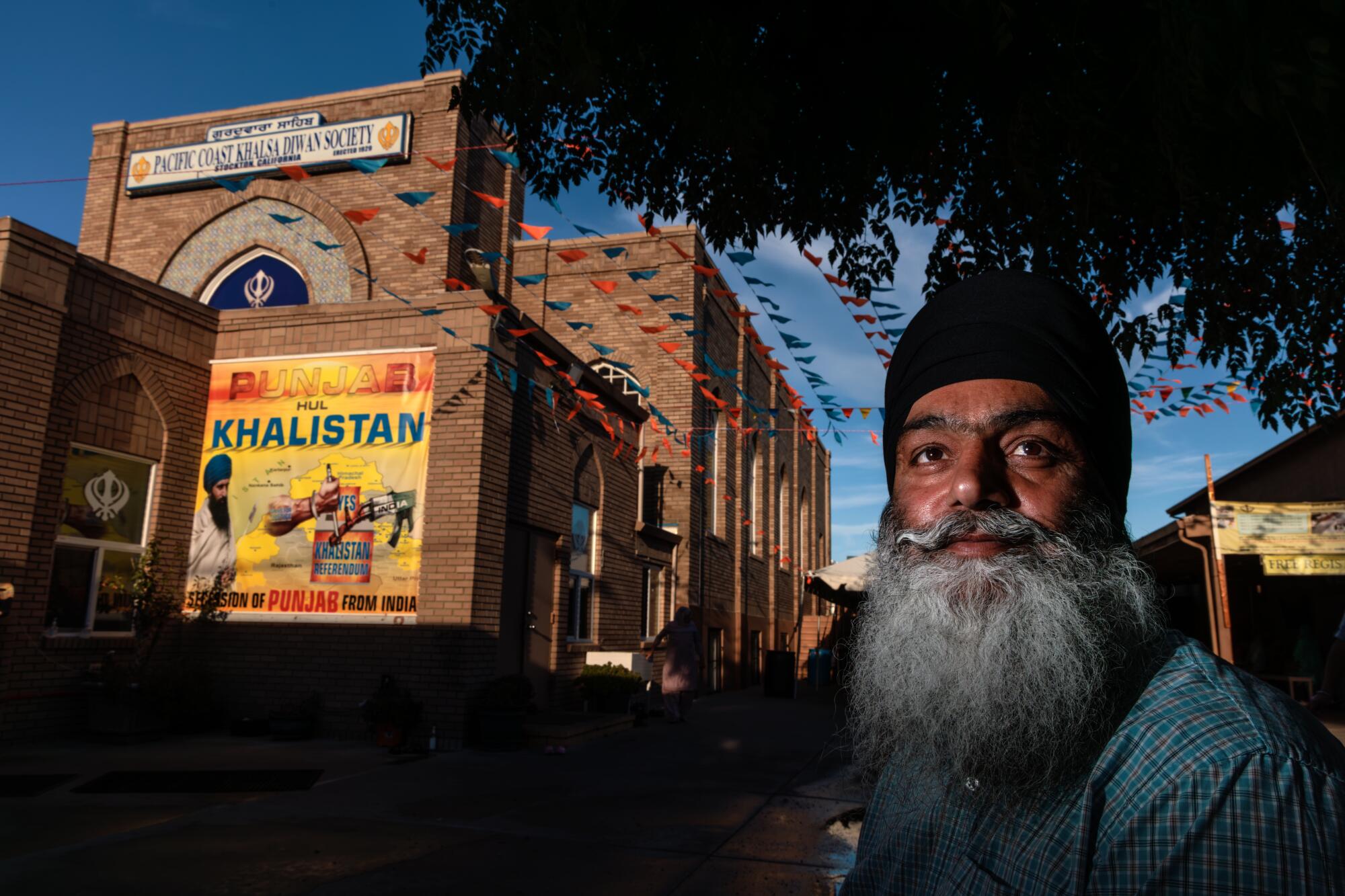

At the center of the separatist movement is the oldest Sikh house of worship in America: the Gurdwara Sahib, a collection of modest brick buildings located near a rail yard just south of downtown Stockton.

U.S. authorities have announced murder-for-hire charges against an Indian man who they say plotted to assassinate a U.S. citizen in New York City.

Congregants acknowledge that some Sikh groups advocate violence in the push to create a breakaway republic where members of their faith can live without discrimination or fears that the Indian government will seize their farmland. But they say their own efforts are limited to peaceful protest and referendums to demonstrate support for Khalistan among the diaspora.

“We fight with the ballot not the bullet,” says Sukhwinder Singh Sidhu, who lives in Stockton and owns a trucking company. “We want our own nation where we can control our destiny. We want to show that the majority of Sikhs want Khalistan, not India.”

The conflict exploded into public view in September when Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau publicly accused the Indian government of orchestrating the assassination of a Sikh activist who three months earlier was shot dead outside his temple in suburban Vancouver.

India denied the claim, but accused Canada of giving “shelter” to extremists and said the activist was the leader of an underground militant group.

Then in a federal indictment in November, the U.S. government said an Indian spy paid a hit man — an undercover law enforcement agent, it turned out — to kill a Sikh activist in New York.

At the Stockton temple, these developments have only fueled the drive for secession.

On a recent Sunday, hymns blared as hundreds of men and women — farmers, gas station owners, truckers, tech workers and physicians — paraded around the temple grounds, singing, banging on drums and hoisting their holy book skyward.

They had come from Yuba City, Sacramento, Modesto and elsewhere in Northern and Central California to celebrate the birthday of one of Sikhism’s 10 spiritual leaders. The faith was established in the 15th century by a former Hindu who preached about the “oneness” of God, promoted gender equality and rejected the caste system.

But the day also paid tribute to two Sikh militants who were executed by hanging after they killed a senior Indian army official in 1986 in retribution for deadly state-sponsored violence against Sikhs.

Addressing the crowd, one fiery speaker praised the assassins as martyrs and their feat as a victory for God. He said that “freedom fighters” would one day prevail through the ballot box.

The congregants joined him in a chant: “Long live Khalistan!”

In 1905, a 39-year-old farmer named Jawala Singh left his home in Punjab and boarded a ship heading east, making his way to Panama and slowly on to San Francisco — an important hub for a growing diaspora.

Like thousands of other Sikhs, he was fleeing famine, malaria and British colonizers.

Looking for business opportunities, he and a Sikh partner leased a 500-acre ranch on the outskirts of Stockton and started farming potatoes. The venture was so successful that he became known as “the potato king.”

At the time, members of Northern California’s Sikh community would gather to pray on the farm. Then in 1912, Singh led an effort to turn an old farmhouse in Stockton into a one-stop shop for job seekers, legal help for new immigrants and scholarships for Indian students at UC Berkeley. It became the temple that now sits at the end of Sikh Temple Street.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Singh, though, was interested in more than worship. Concerned for his family and friends back home in Punjab — which had been an independent Sikh kingdom before the British arrived — he used the temple to launch a movement of expatriates who espoused armed revolution to overthrow the colonizers.

In the summer of 1914, after touring the West Coast to recruit fighters, he sailed to Kolkata, where he was promptly arrested for conspiracy to overthrow the British Empire and spent the next 18 years in prison.

Singh died in 1938 of injuries in a bus crash in what is now Bangladesh. At the Stockton temple, his photograph is on display in the original farmhouse, now a library and museum. Congregants affectionately call him Baba Singh.

The push for a Sikh nation lost momentum with Indian independence in 1947, but it picked up again two decades later after the Indian government redrew the borders of Punjab, significantly reducing its size, and redirected rivers away from Sikh farms.

Khalistan — which means “land of the pure” in Punjabi — became a rallying cry as clashes erupted between Sikhs and soldiers.

The strife peaked in 1984 after Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ordered a deadly siege on separatists occupying the Golden Temple in Amritsar, the holiest site in the Sikh religion, and a bullet pierced a copy of the Sikh holy book, considered to be an eternally living guru.

In retaliation, two Sikhs working as guards for the prime minister assassinated her. Hindu mobs went on a killing rampage around Delhi, often with government approval. Estimates put the number of Sikh deaths as high as tens of thousands, leading some to describe the violence as a genocide.

A year later, militants blew up an Air India flight over the Atlantic, killing 329 people.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau says Canada is investigating whether India is linked to the assassination of a Sikh Canadian citizen in British Columbia.

As India cracked down on Sikhs in the name of fighting terrorism, the militancy faded and more Sikhs left the country.

It is unclear today how much support the Khalistan cause has in India, home to 80% of the world’s 25 million Sikhs.

A 2021 Pew Research Center survey of Sikhs in India found that 95% were “very proud” to be Indian, while 70% said that respecting India as a nation was part of Sikh identity.

But Harjeet Grewal, a professor at the University of Calgary in Canada and an expert on Sikh history, said he doesn’t trust such polls or the Indian government’s position that the push for Khalistan is a fringe movement. He suggested support is coded in the kinds of chants about Sikh freedom that farmers in Punjab employed during recent protests against government plans to enact new laws setting crop prices.

“Simply saying the word ‘Khalistan’ can label you a terrorist in India and bring upon you all the restrictions on civil rights that comes with that,” Grewal said.

The most vocal supporters of the cause are among the Sikh diaspora.

Only Britain and Canada have bigger Sikh populations than the United States, home to about 500,000, half of whom live in California. Men in the faith are easily recognizable since many have long beards and wear colorful turbans that hold up their uncut hair.

In Stockton, Sikh-owned restaurants and other businesses abound. A Sikh trucker and financial advisor recently ran for City Council but lost.

With thousands of members from across Northern California, the Gurdwara Sahib is a focal point of debate over the tactics of the secessionist movement.

Set in a neighborhood of single-story houses, the temple complex includes a religious school, a prayer hall, two cafeterias and an exhibit on Sikh American history showcasing a hand-cranked printing press that temple founders used to produce newspapers calling for the overthrow of British colonizers.

Flying high over the property is a blue flag emblazoned with the word “Khalistan.”

Bright yellow banners hanging from the buildings sum up the campaign for self-determination. The graphics show a traditional Sikh dagger stabbing a machine gun barrel painted orange, white and green — the colors of the Indian flag. Inside the blue map borders depicting Khalistan are the defiant Punjabi words “Delhi Banayga Khalistan” — meaning the Indian capital will become Khalistan.

To the Indian government, such imagery is evidence that even secessionist groups that officially espouse peace are fronts for militants. Officials point to prosecutions in the United States for abetting violence.

In 2006, a federal jury in Brooklyn, N.Y., convicted a 44-year-old man from Long Island of “providing money and financial services” to a separatist group called Commando Force, which carried out killings of police in Punjab during the 1980s and 1990s.

And in 2016, a 42-year-old Sikh man from Reno admitted in federal court that he bought night-vision goggles and a laptop for an associate to use in organizing an attack in India. Prosecutors said the man, whose planning included a meeting with a supporter in California, was a member of both Babbar Khalsa International — the group implicated in the 1985 Air India bombing — and the Khalistan Zindabad Force — which India says has been behind several railway and bus bombings there.

Leaders of the Stockton temple say referendums — and not armed struggle — are the path to creation of Khalistan.

“If people want to start fighting, what I tell them is to stay away from our temple,” said Amarjit Singh Tung, a trucker and the temple secretary.

As for imagery at the temple that appears to celebrate armed revolution, including banners paying tribute to dead militants and a museum of martyrs featuring photographs of the prime minister’s assassins and other gun-toting Khalistan supporters killed during conflicts with Indian authorities, Tung said those men “fought for freedom because they had no choice.”

“It is not Sikhs who started the aggression,” he said. “And we here in America are not fighters in the same way but we have the same goals.”

Tung has also made clear that acceptable tactics do not include destruction of property. In separate incidents over the last year, windows were smashed at the Indian Consulate in San Francisco during a pro-Khalistan rally and pro-Khalistan graffiti was scrawled on two Bay Area Hindu temples.

Most Khalistan activism at the Stockton temple happens through a 17-year-old group called Sikhs for Justice, which describes itself as a human rights and education organization and runs on donations.

There are 3.5 million truckers in the United States. California has the second-most after Texas. As drivers age toward retirement and a shortage grows, Sikh immigrants and their kids are increasingly taking up the job.

From an office in Astoria, N.Y., its lawyer and spokesman, Gurpatwant Singh Pannun, the man whom U.S. authorities say India plotted to kill last year, produces YouTube shows in which he rails against Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi as a Hindu nationalist whose government is increasingly intolerant of other faiths.

Pannun travels frequently to rally supporters. “I am in New York, but in the United States, we are strongest in California,” he said.

In the last few years, according to the group, more than a million Sikhs have participated in its referendums in London, Vancouver, Rome, Geneva, Melbourne and San Francisco. Another vote is scheduled for March 31 in Sacramento.

The group, which administers the referendums through a third party, has said no results will be released until a vote is held in Punjab — something the Indian government would never allow.

India’s ambassador to Canada recently called the referendums “a futile effort.”

Not all the congregants at the Stockton temple take a deep interest in politics. Some simply come to pray.

Harpreet Kaur, 31, started attending services in Stockton after her marriage two years ago because her husband was a member.

“We support it but we watch it from afar,” she said. “It’s not our passion.”

But as the international conflict intensifies, several Sikhs in Stockton said they have received threats.

Sidhu, the trucking company owner, recently answered his phone to hear a man shouting Hindi expletives threatening to “finish” him.

“Even though we do not want to fight with our hands, I will tell you, we are not afraid to die,” Sidhu said.

Bobby Singh, a 24-year-old student at Sacramento State, recently received a text that said: “You’re next in the USA. We have all the tools ready to come to fix the problems.”

The sign-off was “Jai Hind” — “Long live Hindustan,” which is how some Hindu nationalists refer to India.

The temple has a security guard and cameras to watch for suspicious visitors. It’s in regular touch with FBI agents on threats.

Singh said he believes primarily in supporting the creation of Khalistan through democratic means. But he added: “Don’t tempt us to use alternative routes. We will lay our bodies for the Sikh faith and the cause.”

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.