- Share via

The daytime bustle on Sunset Boulevard was giving way to nighttime flash. Netflix employees were badging out of the Icon, the streaming giant’s cantilevered glass tower. The tire shop was closing up, and tenants at the Harold Apartments were climbing the spiral staircases to their rooftop decks.

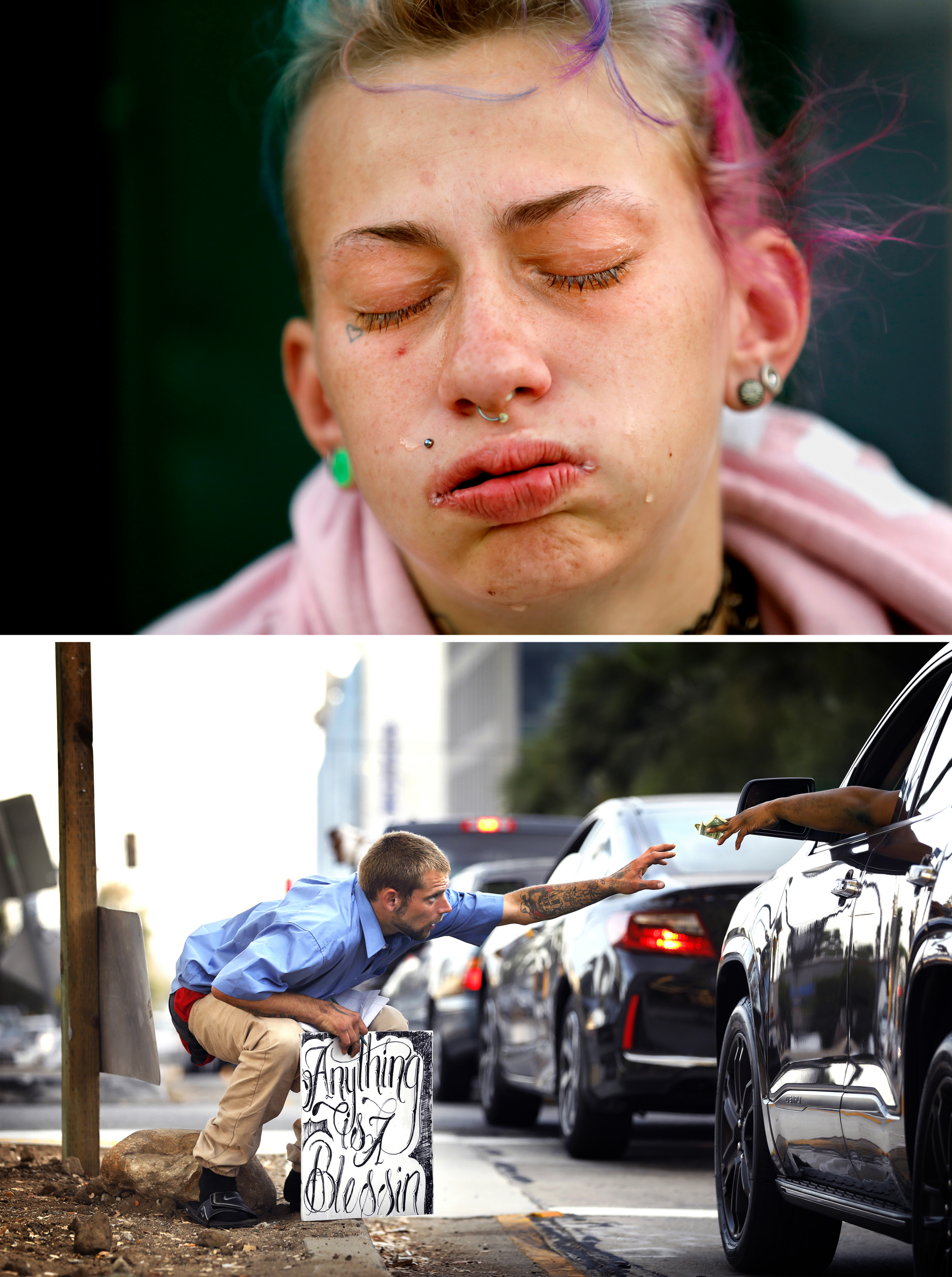

Nearby, Mckenzie Trahan stood outside the Denny’s restaurant, sobbing into her phone.

A hole in a chain-link fence around the restaurant parking lot opened onto a ragged train of tents. They clung to a steep embankment above eight lanes of whooshing traffic on the 101 Freeway. From her vantage point, Mckenzie should have been able to see her encampment.

But while she was in court, a Caltrans crew had cleaned her out. Everything was gone: the tent with built-in lights, a blow-up mattress, a new laptop, her birth certificate, housing papers and prenatal vitamins.

“I was like, ‘No, no, no, hell no,’ ” Mckenzie said, recalling that August 2018 evening. “It’s like my whole city was against me.”

Mckenzie was 22, and 6½ months pregnant. Her boyfriend, Eddie, 26, was HIV-positive, although his viral load was undetectable and he could not transmit the virus through sex.

Two weeks before she learned she was pregnant, they had broken up. He was not himself; at times he walked around the Denny’s parking lot talking to himself. (The Times is withholding his full name to protect family members’ privacy.)

“It’s like he’s there but he’s not,” Mckenzie said.

She made an appointment for an abortion but couldn’t go through with it. Still, she remained “terrified” of having the baby. The odds were heavily stacked against her raising her child to adulthood.

Mckenzie’s family came out of poverty in Louisiana’s Cajun Country, and for three generations had been buffeted by domestic violence, mental illness and homelessness, and caught up in child welfare cases. Her mother, Cynthia “Mama Cat” Trahan, was taken from her mom at age 5 and placed in foster care. Mckenzie and Cat were homeless on and off during her childhood, and Mckenzie was also put in foster care.

For coverage of two of the most troubling and intractable problems facing Southern California — homelessness and racial division — the Los Angeles Times won two Pulitzer Prizes.

Young adults who age out of foster care after such heightened trauma are at serious risk of repeating the cycle of homelessness and losing their kids to foster care. It’s an ominous harbinger for Los Angeles, where multigenerational homelessness is not uncommon — and the system is not equipped to meet the needs of people with such profound struggles.

“The homeless system is not designed to address and unpack all of the other systemic failures that have led somebody to where they are today,” said Heidi Marston, who resigned in May as executive director of the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority.

Mckenzie is clear that she has made bad decisions. She ran away at age 11, started using drugs, and was in and out of juvenile hall and foster care placements. As an adult, she racked up three felony convictions for possession of meth for sale and receiving stolen property. She had shot up meth for two years before stopping several months before she became pregnant, and was still on probation in one case when she got the news.

“I feel like my whole life has just been written for me. I’m just supposed to be stuck here. I’m not supposed to get any further.”

“A typical f—up, I guess,” she described herself ruefully.

But she longed for a better life.

“I feel like my whole life has just been written for me,” she said. “I’m just supposed to be stuck here. I’m not supposed to get any further.”

Mckenzie Trahan — or as her scalp tattoo put it, one of “Hollywood’s Finest” — was born into a family that for three generations had been buffeted by domestic violence, mental illness and homelessness, and caught up in child welfare cases. Read our series, watch our videos and see more photos.

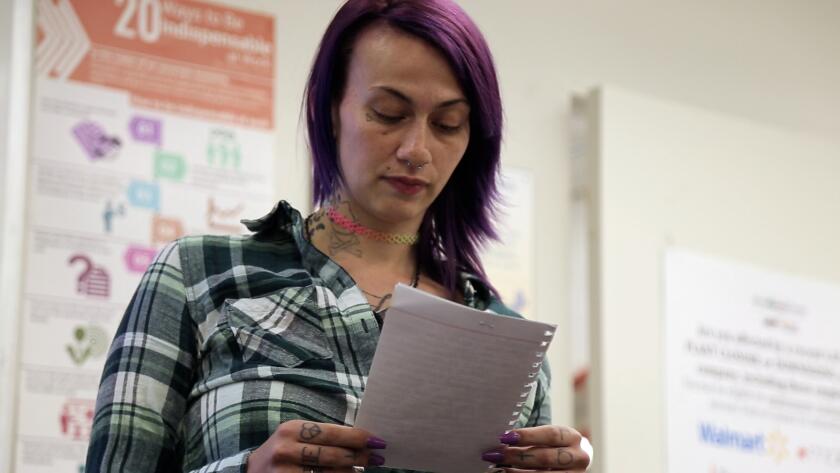

Mckenzie was determined, focused and quite bright given her lack of education, said Leslie Kerr, her case manager with The People Concern, a homeless services nonprofit. When other homeless people at an encampment sweep screamed at sanitation workers, Mckenzie read the crew the city cleanup regulations.

She survived growing up homeless with her sparkle and wit intact; as one police officer who works with homeless people put it, Mckenzie seemed “destined for a much better life.”

A child would need her, Mckenzie reasoned, “whether it was only for pregnancy or the rest of their life.... They couldn’t live without me. Everybody wants to feel needed.”

She called her mother for guidance.

“This is your chance, baby girl,” said Cat, then 57.

“I was like, ‘You bitch! Now I have to keep it,’ ” Mckenzie recalled later, laughing and crying together.

The happy family she didn’t have

Mckenzie sat on the curb outside Denny’s as the afternoon light died away. In the half-empty parking lot behind her, a man worked out with a jump rope; a truck’s headlights played across her high cheekbones.

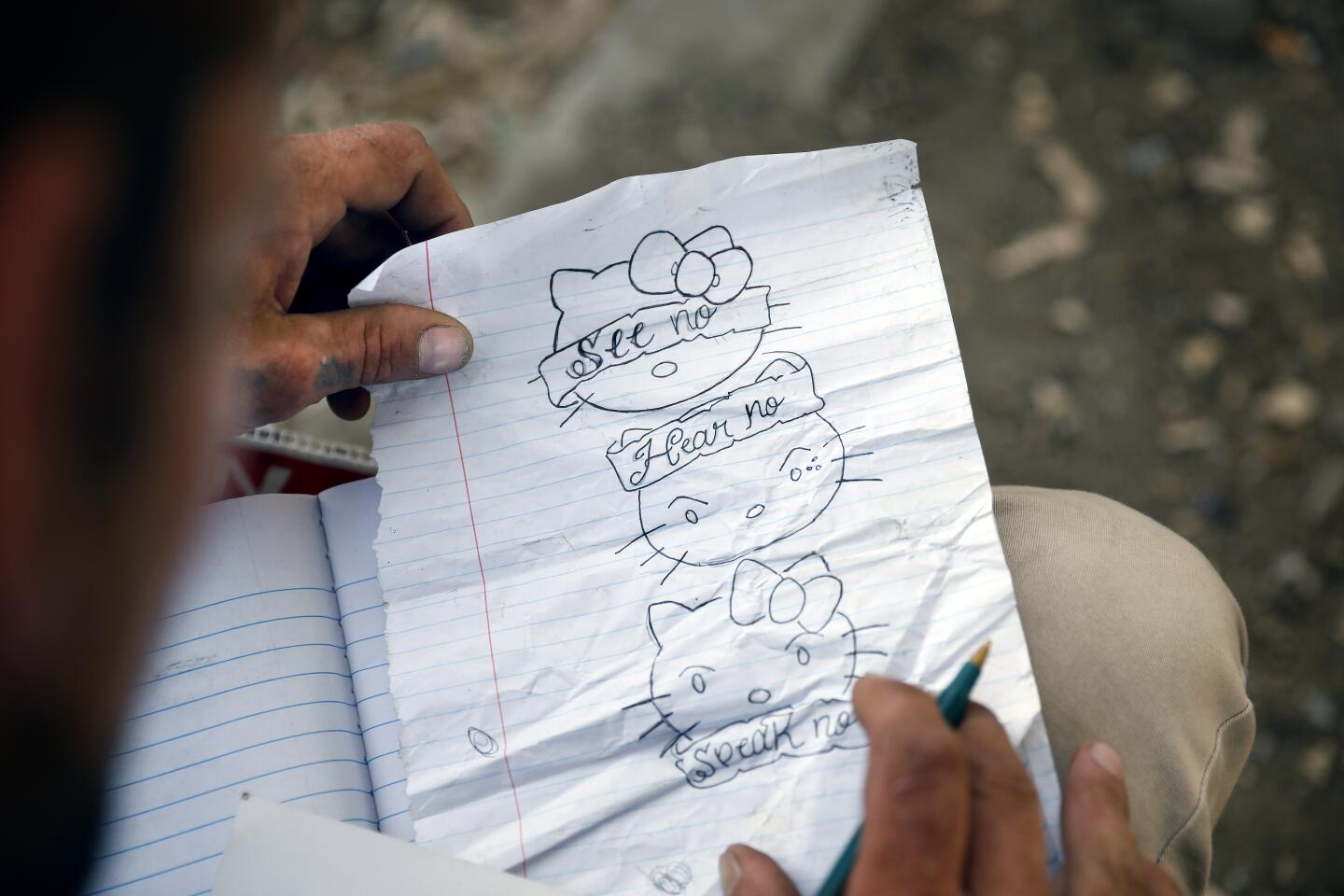

Tall and slender with pastel rainbow-colored hair, almond eyes — and a gap between her front teeth she was quite proud of — Mckenzie had a shaved swoop on the side of her scalp tattooed “Hollywood’s Finest.” She dressed mostly in pink and purple, and her tent held an array of Hello Kitty merchandise, an amplifier and other electronic equipment she used to work on her rapping. At age 16, Mckenzie held her own against a grown man in a Las Vegas freestyle rap battle.

Despite L.A.’s stifling September heat, she was wrapped in a heavy pink sweatshirt, sniffling and blowing her nose. Now 7½ months pregnant, she had developed a serious respiratory infection; three of her homeless friends moved into her tent to help her recover.

She wore a ’90s-style punk choker and a necklace with a pendant shaped like brass knuckles. Her street name was Stitches — because that’s what you get if you mess with her or her friends, Cat said: “She’ll bust you up, but she’s compassionate.”

Mckenzie talks freely about dope dealing in the past to support her meth habit, about people she‘s beaten up and others she‘s protected since she landed on the streets of Hollywood at age 13. That’s how she survived; that and the support of her friends — mainly homeless teens from the foster care or juvenile justice systems, scarred by economic marginalization, and some by racism as well.

Finding a homeless woman in an advanced stage of pregnancy in a tent in the heart of Hollywood’s real estate boom is shocking. But for young women with backgrounds like Mckenzie’s, homelessness and motherhood are often less a decision than a destiny.

Homeless young women are nearly five times more likely to become pregnant — and more likely still to experience repeat pregnancies — than those who are housed. More than 4 in 10 homeless women in Mckenzie’s age group — 18 to 25 — were pregnant or already mothers, according to a nationwide survey released in 2018 by Chapin Hall, an independent policy research center at the University of Chicago.

Experts cite several dynamics at work. Planning of any kind, including reproductive, is uncommon for those in the grind of homelessness. Families and partners who don’t want the worry of a child sometimes throw women out when they become pregnant.

Young women may take on partners to protect against rampant sexual assault in the streets, and many of their partners don’t wear condoms. And some women with troubled domestic histories feel a deep pull to create the happy family they never had, one they believe will not be ripped away.

“A baby could represent new possibilities … something unsullied by all the tragedy the individual has experienced,” said Khiara Bridges, a UC Berkeley law professor who has studied poverty and pregnancy.

“These women have hopes and dreams like anybody else,” said Heather Carmichael, executive director of My Friend’s Place, a leading Hollywood youth homeless agency.

A confusing and fragmented network of maternity homes, shelters and transitional living programs serve pregnant homeless women in Los Angeles, but capacity is limited, some agencies push religious messaging, and few take boyfriends or pets.

From 2020 through 2021, the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority screened 1,413 homeless pregnant women; 229, or 1 in 6, were housed through the agency.

‘A homeless runaround’

Back at the Denny’s parking lot, Mckenzie turned the conversation to her childhood — “more of a homeless runaround,” she called it, a blurry flip-book of motel rooms, shelters and the inside of the van where she and her mother often stayed.

They bounced from state to state, never sinking roots, she said.

“Any time we would face an issue we would flee,” Mckenzie said, sneezing into the elbow of her fleece top. “I’m not saying she wasn’t a good mom.”

In another conversation, Mckenzie elaborated: “Like, she rebutted with crazy and I rebutted with crazier.”

Cat has struggled with poverty, and suffered mental and physical health issues, domestic violence and the loss of Mckenzie and a son to foster care.

At age 11, Mckenzie ran away, started using drugs and landed in juvenile hall in Nevada. The next year, she and Cat moved to Ventura for a fresh start, but the suburban beach culture was a tough fit for a girl from a poor, semirural Southern background, who by her own description dressed like a little boy.

Mckenzie was molested by a friend’s stepfather, according to Ventura County Superior Court criminal records, and landed in a psychiatric facility and then a group home, her mother said in a civil lawsuit. As an adult, Mckenzie would be diagnosed with severe anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

She went AWOL from one foster care group home after another. From a home for troubled girls in La Verne, she caught a bus for Hollywood.

Her Hollywood street crew

It was fun at first, Mckenzie said.

She was one of the face-painted fans known as Juggalos who followed the outsider band Insane Clown Posse. The group had a big homeless following; 15% of those surveyed at a Los Angeles youth drop-in center in 2016 identified as Juggalos.

She and her friends fought and caroused up and down Hollywood Boulevard, sleeping on cardboard on street corners or in doorways. They forged informal family relations, with play moms, dads and sisters, and formed a street crew called Dedikated Soldiers, or DKS, an offshoot of an older homeless group, the Hollywood Dogs.

Mckenzie was named the crew’s “keyholder,” the youngest ever with that title, she said, with authority to kick thieves or molesters out of Hollywood tents and settle disputes.

But Hollywood could be treacherous. She recounted how a man she sold dope to handcuffed her to the toilet in a Hollywood motel room, shot her up with cocaine, heroin and speed, and tried to beat her into becoming a sex worker.

“I ain’t never been a prostitute in my life, and never will be,” she said.

The man took her to the Jack in the Box restaurant on Sunset, which unbeknownst to him was the DKS kick-it spot. Her friends beat him up and freed her.

Days later, police picked her up on a juvenile probation violation after finding her in the stairwell of a Bed Bath & Beyond store on the ground floor of a swanky new condo building in Hollywood. Chunks of her hair had been torn out and she weighed less than 100 pounds, said Mckenzie and Cat, who had been just blocks away searching for her daughter.

Sources of support

Back at the Denny’s parking lot, the sky had turned leaden gray, and Mckenzie bummed a cigarette from her best friend, Christina Bojorquez.

As kids, Mckenzie and Bojorquez had stayed together in Hollywood “bandos,” or abandoned buildings, and their relationship turned romantic after Mckenzie’s breakup with Eddie. Mckenzie planned to move in with Bojorquez if her friend got an apartment before the birth.

“My only salvation is her,” Mckenzie said of Bojorquez, tearing up.

But Eddie had also been her friend since her early teens, and her steady boyfriend for 2½ years. He took her in when she got out of jail, and rescued her when she took a bad meth shot and lay immobilized for days in a tent.

“Eddie came and saved me,” she said, crying again.

Mckenzie and Eddie got back together. Her mother arrived from St. Louis and set up a tent in the dirt next to Mckenzie’s camp to help with the pregnancy and birth. Mckenzie launched a frantic search for a program to take her in before the baby was born.

Prenatal care, street style

In September, Mckenzie caught a bus and a train, then hiked up a steep hill in the scorching sun to apply for housing at the Los Angeles Dream Center in Echo Park, an arm of an evangelical megachurch with homelessness and drug abuse programs. In an email, the group rejected her as “incompatible” with their operation.

Later that month, on her 23rd birthday, Mckenzie signed papers to move into PATH Gramercy, transitional housing for 16 women ages 18 to 24 who are expecting or have children under 5.

Kerr, her case manager, was driving Mckenzie to her first ultrasound appointment at the Universal Community Health Center in Los Angeles that month when the phone rang. The appointment had been called off because the clinic wasn’t equipped to handle a “high-risk” pregnancy.

The clinic referred her to Adventist Health White Memorial hospital in Boyle Heights, which for generations had delivered babies for people regardless of their financial or insurance status.

In October, at an obstetrics office adjacent to the hospital, Dr. Dominique Luckey noted that Mckenzie’s baby bump looked small for a late-stage pregnancy — a concern because low birth weight, which is often associated with drug use, can affect the baby’s health. A flicker of apprehension played across the OB-GYN’s face as she slid the ultrasound wand across Mckenzie’s stomach.

Relief: With her long, lanky body, Mckenzie was “carrying small,” said Luckey, who scheduled a caesarean section delivery in 11 days. The doctor suggested waiting to learn the gender, but Mckenzie wanted to know now.

“It’s a girl,” the doctor said.

Mckenzie was elated. “I told you!” she said to Eddie, beaming.

He looked down at the ground, eyes closed and head in hand.

“Don’t you want to see?” she asked, presenting a sonogram printout from the ultrasound. “I f— hate you, Eddie.”

Mckenzie FaceTimed her mom and showed her the sonogram.

“It’s a girl!” she said.

“You’re having another Stitches?” her mom said.

“Hello Kitty everything, yes,” Mckenzie murmured as she walked out of the exam room.

‘I couldn’t even imagine not having her’

The next day, Kerr helped Mckenzie move off the street. Mckenzie, her tattooist and other friends loaded her amplifier, guitar and makeup case into Kerr’s car.

“We’re proud of you!” friends called out as Mckenzie and Kerr drove off.

“They got her through this pregnancy,” Kerr said. “They took care of her.”

Mckenzie’s phone rang: “This is the North County Correctional Facility.… To hear your payment options, press 1.”

“Face!” Mckenzie cried over the jail phone line, addressing her friend by his street name. “Dude, I’m having a girl!”

Mckenzie was terrified of the delivery — her third C-section and the final one the doctors said they would be able to perform safely — and had been frantic that she didn’t have clothes and other necessities for a baby. After finding a layette, bassinet and other baby items in her new room, she gave a teary-eyed thanks to PATH family programs manager Elizabeth Jimenez.

Ten days later, Kerr and Mckenzie screeched past a sign reading, “Don’t abandon your baby,” and into the parking lot for White Memorial’s labor and delivery center. “We’re having a baby!” Kerr shouted.

It was the hospital’s tradition to announce every birth by sounding chimes in the waiting room. They rang at 3:47 p.m. for Ann, 19.5 inches, 6 pounds and 11 ounces. Both mother and child were healthy and HIV-free. (Ann’s full name is being withheld to protect her privacy.)

“I’m just glad we did it, you guys,” Mckenzie told visitors from her recovery bed. “I couldn’t even imagine not having her now.”

Cat noted with satisfaction that the hospital staff had treated Mckenzie with the same care and respect they would extend to any new mother.

“She’s perfect,” Eddie said. “Her mother is beautiful and I’m handsome, so I knew she’d be beautiful.”

Mckenzie was alone when social workers appeared at her hospital bedside days after the birth to investigate a report that the baby was being neglected.

She was not Mckenzie’s first child.

At age 16, Mckenzie was living on the streets of Los Angeles with her first boyfriend, Sean, when she realized she was 4½ months pregnant. Their son was born in April 2013, and Mckenzie, Sean and the baby moved with her mother, Cat, into a converted garage in Mid-City.

Sean and Cat fought bitterly, and there was tension with the landlord. Mckenzie was alone when a social worker arrived three months after the birth.

A dependency court report would later describe the home as filthy, and the social worker accused Mckenzie of smoking marijuana and possibly other drugs around the child. (Mckenzie said she never used drugs around her children.) The boy was taken away and Mckenzie was sent to a group home, she said.

Mckenzie was given “family reunification” services including counseling but says she was homeless and couch surfing, and didn’t keep up with required visits to the far-away foster home the boy was placed in. He is now being raised by his paternal grandmother.

Mckenzie connected with a new partner, Anthony, and graduated from smoking meth to injecting or “slamming” it. Pregnant again at 18, she got clean and moved into a residential program run by St. Anne’s Family Services for homeless expectant mothers with foster care or juvenile detention histories.

Mckenzie’s second son was born in January 2015. Anthony went to prison, Mckenzie relapsed, and she was later jailed herself.

“I feel like I just pop babies out. I can’t call myself a mom because I’ve never been there long enough to be a mom.”

Mckenzie had entrusted the baby to a friend so he wouldn’t be homeless, dependency court documents say. Mckenzie said she was unaware of the friend’s checkered child welfare record in other states. The baby was taken from the woman, the records state, and custody was awarded to Anthony.

Mckenzie’s feelings about her first two children are complicated. She expresses shame and anguish that they were taken from her, and regrets that she didn’t have a chance to celebrate their birthdays with them or to walk through the park with one clinging to her finger, as she had seen other children do with their parents.

“I feel like I just pop babies out,” she said, wiping away tears during a sidewalk conversation outside Denny’s. “I can’t call myself a mom because I’ve never been there long enough to be a mom.”

Mckenzie is also proud of her boys and grateful that family members are raising them, and says she will always love them and their fathers for helping to give them life. The boys’ names are tattooed on her chest and arm, and she hopes they might get to know her when they are older.

“The point of me getting the tattoos was to remind myself every time I looked in the mirror that I was a mom — that I was something more,” Mckenzie said.

But she didn’t know how to care for herself, much less a baby, when her sons were born, Mckenzie said. This time would be different — she was certain.

Eddie had committed to co-parenting. Her mother was at her side. She had bonded with Kerr, her case manager; Kerr said Mckenzie really wanted the baby this time.

And PATH Gramercy had a lot of success in helping young pregnant women get off the street and form families — even women like Mckenzie who missed “the growing-up part,” as she put it.

“Not that many give up,” said Cheryl Davis, PATH housing navigator and client advocate.

During their time together, Mckenzie Trahan did everything the Los Angeles homelessness system asked of her, case manager Leslie Kerr said.

‘Homelessness is not neglect’

Mckenzie said she wasn’t sure whether the social workers who came to her hospital bedside knew about her older children. They expressed concern over Eddie’s HIV-positive status and her past drug use.

“She’s two days old, dude, and there’s 13 people taking care of me,” she told the investigators dryly. “I’m in a hospital.... Nothing is happening.”

Still, she was apprehensive. Neglect charges — brought when a parent does not physically abuse a child but fails to provide adequate food, shelter or supervision — account for most removals to foster care, including nearly 90% of the cases in Los Angeles County over the last five years.

“I’m terrified,” Mckenzie sobbed to Kerr. “They’re trying to take my daughter away.”

In January 2019, Mckenzie and Eddie met with the county Department of Children and Family Services to discuss their baby’s case. Mckenzie walked out of the agency’s office south of downtown Los Angeles crowing.

“She said homelessness is not neglect!” Mckenzie said. “That’s the first time in the history of social work a social worker ever said that.”

But her fears turned out to be prescient. The neglect case had been ruled inconclusive — not closed, as Mckenzie had thought.

‘Get up, it’s your turn’

Other potential land mines were waiting when Mckenzie and her baby left the hospital for their apartment at PATH Gramercy.

The program provided transitional housing and social services to help young mothers get jobs and save money for subsidized housing elsewhere. They would have to pay 30% of their income in rent and a government voucher would cover the rest.

Homeless women with children were in desperate need of housing, and families in the surrounding neighborhood of Arlington Heights clamored to get into PATH Gramercy’s top-tier on-site day-care center, which had well-trained teachers, fresh-cooked meals and a shady playground.

But PATH was planning to shut down the child-care center and convert Gramercy’s handsome brick building to staff offices and apartments for homeless single adults. Mckenzie had heard the closure could come in as few as seven months, at a time many homeless people in Los Angeles were waiting close to a year for a rent voucher.

PATH was opening three other interim housing projects, including one for women and children, and administrators promised no one at Gramercy would be turned out into the streets. Still, the deadline weighed heavily on Mckenzie, who was laser-focused on finding a permanent home that couldn’t be snatched away.

Mckenzie’s studio apartment on the second floor of Gramercy had a kitchenette and bathroom, and she brightened it with drawings of dolphins, a feathered dream catcher and cutouts of Winnie the Pooh, Eeyore and Disney villains. A Hello Kitty tank top hung from the dresser knobs.

PATH had a no-visitor policy, which meant neither Cat nor Ann’s father, Eddie, could come into the room. Mckenzie found herself largely alone, 24/7, with a newborn. For a young woman whose adolescence was spent in raucous homeless encampments, the isolation and quiet were a shock.

“God, I miss the freeway noise,” she said one afternoon, switching on the air conditioning.

Eddie was staying in other homeless housing a couple of miles away. Mckenzie and Eddie would meet halfway and walk hand in hand down Washington Boulevard. Mckenzie daydreamed about moving into one of the shabby but stately foursquare houses around Gramercy. Eddie had a master gardener certificate from another program for homeless people; maybe he could be a groundskeeper.

But she missed Eddie’s help at her apartment, especially when Ann would wake up crying in the middle of the night.

“I want to be in a place with my dude and say, ‘Get up, it’s your turn,’ ” Mckenzie said.

Mckenzie FaceTimed a stream of photos of Ann to her mother and friends. But she had little time for socializing; her days were filled with appointments to clear up the medical, legal and financial problems left over from her years in the street — what one social worker called “the wreckage of homelessness.”

Confronting ‘the wreckage’

Mckenzie’s teeth were in bad shape; she needed extractions and crowns. And hauling Ann in her stroller up the steep staircase in the aging Gramercy building — there was no elevator — aggravated the young mother’s old back problem and her C-section incision.

Court dates on an old criminal charge, monthly hand scans at the probation office, and meetings with counselors and other members of her homelessness services team also gobbled up her time. Transportation was a chronic stressor: Ann’s vaccinations and well-baby checkups were an hour‘s bus ride away in Boyle Heights.

In January, Mckenzie and Eddie volunteered to be tested for drugs. She wanted to show authorities they were no longer using. “Not that there’s anything to worry about,” she said.

The intake person at the Turning Point drug testing center in Baldwin Hills greeted Mckenzie icily. “Your name is not on the list,” she said. A sign on the wall read, “Effective Oct. 3, 2016, water will only be sold. Small bottle 50 cents, large bottle $1.”

Mckenzie made repeated calls on her cellphone to have authorization for drug testing sent over. At the one-hour mark, the receptionist sent her and Eddie into the hall: “You can only wait in this lobby for 20 minutes.“

“I guess you all made such a big old fuss like we didn’t want to test you. We’re going to take care of you,” the front desk person finally said. Mckenzie went in the back with an empty cup. Both she and Eddie tested clean.

Mckenzie’s services team was made up of staff from three of L.A.’s top homelessness agencies. Her case manager, Kerr, was with The People Concern; Step Up provided a drug counselor, housing navigator and therapist; and PATH assigned her an employment specialist, another case manager and a housing coordinator.

“I think it might have been better if I had one person,” Mckenzie said. But she had signed up with multiple agencies, believing there was safety in numbers; each group had let her down in the past, she said. The path out of homelessness was choked with bureaucracy, and multi-specialist teams were state of the art, endorsed by California’s Legislature.

A plan to house up to 10,000 homeless people on the former Sears campus in Boyle Heights draws backlash from residents.

Although Mckenzie had been addicted to meth for a decade, she was not in a full-fledged substance use disorder recovery program, but met weekly with her drug counselor. Kerr, who is herself in recovery after decades of meth addiction, said Mckenzie needed intensive drug abuse treatment.

PATH Chief Executive Jennifer Hark Dietz said L.A. does not have the capacity to meet the mental health and substance abuse treatment needs of all of its homeless people.

“I don’t think when it comes to these really specific specialty services, like mental health and substance abuse, that there is adequate funding,” Hark Dietz said.

Mckenzie rejected psychiatric medication, at first because she was breastfeeding, but later because, she said, “I prefer to rely on my own coping skills.”

Dressing the part

Gramercy staff strongly encouraged Mckenzie and the other new mothers to find work. (PATH’s federal grant was contingent on increasing women’s incomes.) Mckenzie’s dearth of work experience and felony record were deal-breakers for many employers. But she was determined.

With her rainbow-colored hair, Mckenzie burst like a walking Pride flag in January 2019 into the hushed offices of Dress for Success Worldwide-West, the L.A. branch of a charity that has provided professional attire to unemployed and homeless women since 1997.

Immaculately pressed clothing was arrayed on racks in the South Los Angeles showroom. Skirts were knee-length or longer, nail polish and hose came in nude. Mckenzie chose a bunchy straight black skirt and a dowdy plum-colored button-up.

“I’m going to find a blazer,” said her volunteer stylist, Karen Cohen.

“What’s a blazer?” Mckenzie responded.

Mckenzie said she planned to dye her hair one color and grow out her under-shave to cover the “Hollywood’s Finest” scalp tattoo. A stylist remarked that tattoos are no longer taboo in the workplace.

“I have a criminal background and tattoos. I’m trying to minimize the barriers,” Mckenzie said.

After smiling appreciatively at her image in the mirror, Mckenzie twirled for her mother, Cat. “I’m a queen!” Mckenzie said.

“I have a criminal background and tattoos. I’m trying to minimize the barriers.”

Mckenzie filed online job applications, but by January only one employer, Subway, had offered an interview, she said.

“Hell, yes, I want an interview,” she said. “Let me put on my face,” she told Ann, who was fussing on the bed, as she took off her punk choker chain and slid into conservative black pants.

“I think I’m going to get a job,” she said. “I’m so scared.” She did the interview but said she never heard back.

Just say no to Hollywood tents

A month later, Mckenzie caught a bus from Gramercy to Los Angeles Trade Technical College, a site for Project ImPACT, a $6-million jobs and behavioral health program for people with criminal backgrounds that her service providers thought offered her the best chance at employment.

Facing her first-ever separation from her 3-month-old, Mckenzie nervously threw together a diaper bag with extra clothes and bottles and dropped Ann off at Gramercy’s ground-floor child-care center.

“Mommy doesn’t want you to go, but you have to,” Mckenzie wailed, handing the baby to a teacher.

At Trade Technical College, Mckenzie walked warily down the glistening fluorescent-lighted hallways, looking as if she’d been taken hostage.

“I never went to high school, dude,” she said as she approached the ImPACT office. She was so rattled that she couldn’t recall whether the K in her name was capitalized.

The two-week program offered individual counseling and a career readiness assessment, workshops, group sessions and classes in cognitive behavioral health — a regimen aimed at stopping participants from returning to crime or substance addiction patterns.

The program also set participants up with job training. An ImPACT staff member suggested Mckenzie try waitressing because he thought her good looks would lead to good tips. Mckenzie instead got a certificate as a forklift operator, which would employ her street-honed mechanical aptitude. (She once fixed a broken car bumper with a butane lighter and zip ties.)

Mckenzie shone in the program, said Jonae Watts, her employment specialist.

“She had a lot to share about her dreams and aspirations,” Watts recalled. “She was also very engaged in other people’s stories. She has a lot of wisdom.”

At the last class, participants discussed triggers that could rocket them back to prison or addiction. Mckenzie said she had to stay away from the Hollywood tents.

“I’m lonely — believe that — but it’s worth it. I’d rather lose all these people than lose me and my daughter,” she said.

Watts said Mckenzie displayed “the type of pride one would have if you graduated from college” as she stood to read a final statement on her hopes and dreams:

“I needed to accept for a long time that I won’t and haven’t made the best decisions but that my past failure wasn’t the opposite of my success, but my path to my success,” Mckenzie said. “I hope that I can one day ... be so equipped with the skill and experiences that whatever I choose to do I’ll be golden.”

Street angel

Eddie had lost his spot at a Step Up housing program and was living in a giant facility for homeless people on skid row, which Mckenzie refused to visit with the baby. They drifted apart.

Her job leads were way out in Carson, Torrance and Industry; a 1½-hour bus ride was out of the question with her anxiety, she said. PATH had a ride-sharing program, but Mckenzie said she didn’t know about it. (Hark Dietz of PATH said women had to sign up for it in advance and provide invoices.)

Some of the friends she’d made at Project ImPACT got good jobs, but they were exceptions. Only 14% of the program’s fellows were placed in permanent jobs in 2019, well short of the 55% benchmark Mayor Eric Garcetti’s Office of Reentry had set for the program, a Rand Corp. analysis found. (The share who found full-time work rose in 2021 to 44%, Rand found in a follow-up assessment.)

By April, Charlene Tomasik, 54, who was recovering from addiction — and whom Mckenzie described as the guardian angel of Hollywood street kids — had become her main support and chauffeur.

“That’s one of my closest friends as of right now, you know. I don’t know what I would do without her,” said Mckenzie, who had started calling Tomasik “Mom.”

They pooled their food stamps and shopped for groceries together. Ann, now nearly 6 months old, sat in the shopping cart clutching her first balloon.

“Me and her were playing so much yesterday,” Mckenzie said. “I love you, but you’re a weirdo,” she told her.

Like building a rocket ship

As the months passed without a job or permanent housing, Mckenzie wasn’t feeling supported, and her relationship with PATH staff began to fray. A security guard reported that she had left Ann alone in their room; Mckenzie said a woman across the hall was watching her.

A PATH administrator complained that Ann had diaper rash and sniffles because Mckenzie was running around too much. Staff said Mckenzie dropped off the baby’s bottle crusted with milk; Mckenzie said she had lost the bottle brush that PATH gave her and was afraid to ask for a new one.

‘I’m a grown-ass woman. I don’t want to deal with the same s— I ran away from back then.’

Samantha Sowards, a homeless housing consultant, said teaching middle-class life skills to former foster kids who lived in the streets was “not like asking them to go to the moon; it’s more like saying, ‘Build a rocket ship and go to the moon.’ ”

Mckenzie’s friends complained that because of the no-visitor rule, they had to hunker down on the parkway outside Gramercy when they brought her dinner. Homeless housing was turning out to be a lot like her foster placements, Mckenzie said.

“I’m a grown-ass woman,” she said. “I don’t want to deal with the same s— I ran away from back then.”

Meanwhile, Ann was thriving, active and healthy. She sat up early, started crawling at 6 months, and had her mother’s build and physical strength. She loved her teachers, the other kids in day care, and baby YouTube videos on the Cocomelon channel.

She took baths with her mother, and laughed when Mckenzie played peekaboo with her or held stuffed animals to her cheek to plant “kisses.” Mckenzie froze fruit to help Ann with teething.

During day-care pickup one afternoon, Mckenzie put a toy on the floor out of her daughter’s reach. Ann kicked off the ground and flew through the air, Superman style, to grab it.

“Well, I mean, that’s one way to do it,” Mckenzie said with a laugh.

But Mckenzie missed her friends. “I’m not used to being by myself all the f— time,” she said.

“I’m just playing the waiting game, waiting for them to tell me something about my housing,” she said in May 2019. “I couldn’t clean my house because your mind goes other places, dude.”

Stitches goes back to the tents

That June, PATH Gramercy was still open. But Kerr had moved to eastern Washington, Tomasik and her kids had relocated to Las Vegas, and Eddie was living under a bridge. Mckenzie fell into a bone-rattling depression.

While friends babysat Ann, she started hanging out again in the tents of Hollywood, where she was still known as Stitches and admired for her style, chutzpah, and songwriting and rap talents. She tattooed herself and her friends, drew and worked on her lyrics.

She said she could be around drugs without using herself. “Dedikated Soldiers” and “Dedikated Queens” popped up in her social media postings; she said she would always be dedicated to the homeless people of Hollywood.

“God forbid we give up on all those people like they gave up on us,” she said.

A PATH Gramercy administrator said Mckenzie was sleeping or out walking around instead of job hunting. The agency began phasing out the child-care facility’s infant room in anticipation of the remodel, effectively cutting Mckenzie’s babysitting hours. She felt she no longer had enough hours for transportation and work, and decided to put off her job search until she knew where their home and apartment would be.

Before she showed up late one afternoon for day-care pickup, a teacher rolled Ann, looking bewildered, in her stroller into the big kids’ room to wait.

Mckenzie’s PATH case manager was hounding her about relapsing, she said.

“Instead of worrying about and criticizing if I had already gotten high, why won’t you prevent me from getting high?” Mckenzie said later.

The voucher shuffle

Mckenzie desperately wanted out of Gramercy. But progress on her housing voucher had sputtered and then stalled.

Housing vouchers come with conditions and requirements so complicated that some housing authorities hire consultants to hew to the rules. Mckenzie said she initially was told she had been matched to a federal Rental Assistance Demonstration voucher, which provided spots in public housing to formerly homeless people. Mckenzie wasn’t thrilled about moving a baby into the projects but said she didn’t object.

A new consultant switched her application to a Shelter Plus Care voucher for chronically homeless people with mental health or substance abuse issues. Given her history, Mckenzie’s eligibility seemed a foregone conclusion.

But when she went to the county Housing Authority in July 2019, an administrator turned her down for the voucher. Mckenzie said later she wasn’t sure what happened, but she understood that she no longer qualified as chronically homeless because she was in transitional housing; she had to be on the sidewalk or in a shelter to get the voucher.

Mckenzie was dumbfounded.

“What do you mean transitional living means they don’t qualify?” she asked her housing consultant. “It don’t make sense.”

Speaking generally of the voucher system, Tod Lipka, president and chief executive of Step Up, said, “It’s a ridiculous game of cat-and-mouse to make sure someone who has been on the street doesn’t somehow disqualify themselves.”

“I don’t know what I would do if it wasn’t for [Ann] at the end of the day,” Mckenzie said later. “Coming home to this cute child freaking playing and smiling when she sees me — I would have nothing to stop me from just f— going off.”

Cat returned to L.A. that July and again in September. Each visit ended in a blowup, and Cat hit the road again, accusing PATH of failing her daughter.

“These are the type of programs where you hold people’s hand ... you get them to the interview, you hold their hand; and you get them to the doctor’s office, you hold their hand; and you get them to parole.... And it’s not happening,” Cat said in September.

“She’s going to snap.”

‘Stitched,’ the brand

Mckenzie hunched over her laptop in her room at PATH Gramercy in August, freestyle rapping melancholy lyrics to YouTube beats: “The only way to get a meal was to deal.”

“It’s about the crap I’ve been through, especially on the streets,” she said.

Mckenzie said she had looked into temp jobs and paid TV audience work. The dress code — “modern hip” — at one agency threw her for a loop.

There were other ways to make a living than the 9-to-5 rat race, she said. She dreamed of launching a brand called Stitched to market the creative talents of her friends and family in the homeless community: musicians, clothing designers, hairstylists and artists.

“I know some badass musicians, sick guitar players … dope-ass artists or other singers or chicks that know how to cut hair,” she said. “But if you’re not born into money, it’s hard to make money.”

The day-care center closed that month. Some of the kids arrived in party dresses, and parents lingered over sad farewells. Mckenzie was late for pickup.

Mckenzie had begun to plan for Ann’s first birthday in November.

“It’s the first birthday I will get to have with one of my kids,” she said. “It’s going to be a Hello Kitty party.”

That October, Mckenzie and a friend were driving through Bellflower on their way to buy her a car when sheriff’s deputies pulled them over and found a meth pipe and a loaded gun in the vehicle. The friend later pleaded guilty to a gun charge. Mckenzie was arrested on suspicion of felony drug possession.

The same month, a confidential call came in to the child protection hotline alleging that Mckenzie was neglecting Ann. The caller said a room check at PATH Gramercy had found Mckenzie’s apartment in a “nasty” state, with dirty dishes, cigarette butts and spoiled food strewn about, an emergency response social worker later wrote in a protective custody application to the dependency court. Drugs — the caller suspected meth — were discovered in a folded dollar bill in the bathroom, the social worker wrote.

Mckenzie Trahan found herself pregnant and homeless in Hollywood. We get into her struggle to find housing and take care of her child.

Four days later, social worker Todd Johnson went unannounced to Gramercy and found the room in shambles, with trash, cigarette butts and bug spray cans on the floor, he said in a declaration to the court. Johnson said he was shown a picture of a dollar bill with an “unknown crystal-like substance” piled on it.

He gave Mckenzie an afternoon to clean up, and she and a friend thrashed through her toy and clothing bins, trying to clear the jumbled piles. With tears in her eyes, PATH family program manager Elizabeth Jimenez helped Mckenzie gather Ann’s vaccination record and other documents to show Johnson that she was caring for her daughter’s medical needs.

“Poor kid,” Jimenez murmured.

Mckenzie’s drug counselor, Michael Fabacher, later emailed Johnson that Mckenzie had been clean until two weeks earlier but had stopped responding to his texts and calls. Jimenez told Johnson that Mckenzie was not meeting her program requirements and had started displaying “erratic behavior,” coming home late and disappearing without explanation.

Mckenzie denied using narcotics but missed two appointments for mandatory drug tests that Johnson had ordered. A court commissioner approved a warrant to place Ann in protective custody.

Mckenzie met a social worker at a McDonald’s but couldn’t bear to physically hand over her child herself. Her friend put Ann, crying and screaming, “Mama, mama,” into the social worker’s arms, Mckenzie and the friend said.

Days later, Ann turned 1. She was placed in a foster home.

Dirty homes and emotional damage

Sitting cross-legged on the floor in a corner of the Edmund D. Edelman Children’s Court in Monterey Park, Mckenzie was thumbing through phone videos of her daughter while waiting for a hearing to decide whether to return Ann to her care. Her court-appointed attorney, whom Mckenzie had just met, handed her the case documents.

Mckenzie burst into wrenching, heaving sobs. Johnson, in his protective custody application, had checked boxes concluding, without substantiation, that Ann was suffering “severe emotional damage” and was “in danger of physical or sexual abuse.”

Two of the five counts the Department of Children and Family Services had brought against Mckenzie cited her history of drug abuse and dirty homes with her two older children. The other three counts alleged that Mckenzie’s substance abuse, unsanitary home environment, and mental health and emotional problems put Ann at risk of serious physical harm.

Cat said the substance in the rolled-up bill was powdered aspirin she had given Mckenzie for a toothache. There was no mention in the court documents of testing the substance.

The judge reproached Mckenzie for messing up despite the support she had received from the homelessness services system and “detained” Ann, according to Mckenzie and a friend who accompanied her to the hearing. (The court denied The Times’ request to attend the proceeding or obtain a transcript.) Ann would remain in foster care.

PATH offered to place Mckenzie somewhere else, but she refused to return to Gramercy.

Mckenzie later conceded it “was probably not the smartest decision I could have made.” The idea of sitting in a room at Gramercy by herself, without Ann but surrounded by her daughter’s belongings, was for an “addict ... like a nightmare,” she said.

Gramercy “exited” her from the program, bagged up her things and barred her from the building, except by appointment to pick up her stuff. At a storage unit in Hollywood in December, Mckenzie buried her face in Ann’s blanket, breathing in the baby scent.

A month later, in January 2020, Gramercy finally closed its doors for renovation. Mckenzie was living in a tent at the top of a slick, steep embankment lined with encampments above the 101 Freeway south offramp near Sunset. In a year’s time, she had traveled the equivalent of two football fields from her original encampment.

‘My whole world in your hands’

Cat took the news of Ann’s removal hard, accusing Mckenzie of taking her granddaughter’s birthday away from her. Mckenzie replied: “You helped start a battle and then left me alone to fight it.”

The court granted Mckenzie visitation, but she worried that her daughter didn’t seem herself.

“I had them tell me like so many times, like she was fussy, I’m like, what the f—? My baby’s been like laughing since birth. She used to talk so much … [now] she says like mama, you know, that’s it.”

A case plan called for Mckenzie to enter a six-month drug treatment program, undergo weekly random drug testing, and a psychiatric and psychological evaluation and take all prescribed psychotropic medications. She was also required to receive individual counseling from a licensed therapist on keeping a home safe and healthy.

‘You helped start a battle and then left me alone to fight it.’

Mckenzie said she argued that she had been meeting for a year with a drug counselor and had therapy through the Step Up mental health program. She refused to enter in-patient drug treatment unless she could bring Ann with her, and initially refused to take psychotropic drugs, although she later tried anti-anxiety medication, which she said made it harder for her to function. She’s still looking for a prescription that works.

A court-ordered assessment found that Ann had reached all her developmental milestones and was happy, with the exception of the trauma over separation from her mother, Mckenzie said. In her mind, she was being punished for her past, just as she had feared she would when she agonized over the pregnancy.

“I did everything they told me,” she said. “You guys have ... my whole world in your hands right there, you know?” she implored social workers.

Ann holds Mckenzie’s finger

Mckenzie pleaded no contest in 2020 in the Bellflower case to driving without a license and misdemeanor meth possession, although she said she was unaware the contraband was in the friend’s car. She was placed on probation.

Because Ann was no longer living with her, she said she had to go through the voucher application process again. In May 2020 — 1½ years after her arrival at Gramercy — Mckenzie got a voucher and moved into an apartment in East Hollywood.

She sprawled facedown on the bedroom carpet in relief. Her giddiness was cut with sadness over the absence of Ann, present only in the photo gallery Mckenzie had mounted on her wall.

Mckenzie met Ann in parks or at a social service office, and during the pandemic had video chats with her from her apartment. During an in-person visit, Mckenzie’s wish came true: Her daughter held her finger as they walked through the park.

After a shooting on her street, Mckenzie moved to Glendale. Having her own apartment was not turning out to be the panacea she had hoped for, she said.

Her lawyer told her she was “inconsistent” in meeting her visitation schedule and other requirements. Mckenzie’s parental rights were terminated in September 2021, under California law a near-irrevocable cutoff that ended her contact with Ann. Weeping, Mckenzie tore pictures of her daughter off her apartment walls, but later put them back up.

No relative stepped in to take Mckenzie’s child this time. Cat, her grandmother, is still homeless. Cat talks regularly with Ann over FaceTime and said her granddaughter, now 3½, speaks Spanish and English and “is doing great.” But Cat worries she could be pushed out of Ann’s life.

Kerr, Mckenzie’s case manager, said the homelessness system asked the impossible of Mckenzie: to find work, care for an infant, recover from homelessness and maintain sobriety in a matter of months, without a full substance abuse recovery program.

It was “commendable that she got off [drugs] for as long as she did without any kind of program,” Kerr said.

‘We’re still part of the community’

Ann’s father, Eddie, died in January 2021 at age 30 in a head-on collision at Hyperion Avenue and Glendale Boulevard in Silver Lake. A deputy medical examiner report said he had meth in his system. Mckenzie’s close friend Jennifer Miller also died hours after she had been at Mckenzie’s apartment.

In recent months, Mckenzie, now 26, has been drawing, crafting, recording and working on her lyrics and music. She is in a committed 2½-year relationship with Nathaniel Nelson, who is encouraging her to break free of her Hollywood scene and develop her music. “I finally have support,” Mckenzie said.

We met a world of young homeless people above the 101 Freeway in Hollywood, many who had grown up in foster care and the juvenile detention systems.

“I wanna be so many things in life,” she posted on Facebook, “but everything I’ve went through has made my mind have so many barriers to where I’m not sure which route to go or which path to take.”

In October 2021, Mckenzie’s apartment was raided by authorities investigating pandemic “porch pirate” thefts from parcel lockers in the lobbies of Marina del Rey apartment buildings, according to a search warrant. Burglary charges are pending; they both have pleaded not guilty.

Mckenzie has given thought to why L.A. has failed so miserably to fix its stubborn homelessness crisis. Homeless people bear a searing stigma that is hard to shake, she said. As long as housed residents turn their eyes away from people living in wretched conditions, Mckenzie doesn’t see a solution.

“They think it’s like a facade. … Like, it’s really raining, we’re really walking by. And there’s like freaking people just sleeping in the f— rain with no blankets,” she said.

“We’re still part of the community, still part of the world. They just need to show a little bit more dedication in trying to figure out how to make fellow human beings” better.

More to Read

About this story

A feature-length documentary premiered at Big Sky Documentary Film Festival in February. Click here to watch the trailer.

The stories in this series were written by Gale Holland, with photography by Christina House and videography by Claire Hannah Collins. Photo editing by Mary Cooney, Jeremiah Bogert and Kate Kuo. Video production by Erik Himmelsbach-Weinstein. The project was edited by Mitchell Landsberg and Steve Clow, with copy editing by Susan Worrell, Richard Nelson and Dave Bennett. Page design by Allison Hong, with design editing by Taylor Le and Amy King, and additional development by James Tyner and Jim Cooke. Illustrations by Li Anne Liew. Roundtable video interview by Care Dorghalli and podcast episode by Surya Hendry. Newsletter editing by Scott Sandell. Promotion and engagement planning by Mary Kate Metivier and Calvin B. Alagot. Additional digital planning by Lora Victorio.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.