After Uvalde shooting, people consider an ‘Emmett Till moment’ to change gun debate

- Share via

When Ollie Gordon scrolls through social media and her emails, the notifications always come in like clockwork.

The Google alerts she set up for her cousin Emmett Till’s name often surge after mass shootings or incidents of Black people like Trayvon Martin or George Floyd being killed. When she reads comments on Instagram or Facebook, the phrase “Emmett Till moment” is a constant as people turn to social media for solace and community in the aftermath of high-profile violence.

“Anything that happens, trust me, Emmett’s name comes up,” Gordon said.

“We have that moment every day, every time there’s a killing,” she said, adding that she is unsurprised when people make comparisons to Emmett.

Emmett was 14 when he was kidnapped, beaten, shot, lynched and dumped in a river while visiting family in Mississippi in the summer of 1955, after he was accused of whistling at Carolyn Bryant, a white woman. The two white men, one of them Bryant’s husband, who killed Emmett were acquitted by an all-white jury.

Mamie Till Mobley, Emmett’s mother, invited Jet magazine to photograph her son’s mutilated face during an open casket funeral, where she famously said “let the people see” what happened to him. The brutal photo, released just as television was becoming popular and long before social media, shocked the nation and fueled the civil rights movement.

While Emmett’s murder exposed the state’s inherent violence against Black people, his youth also galvanized widespread outrage.

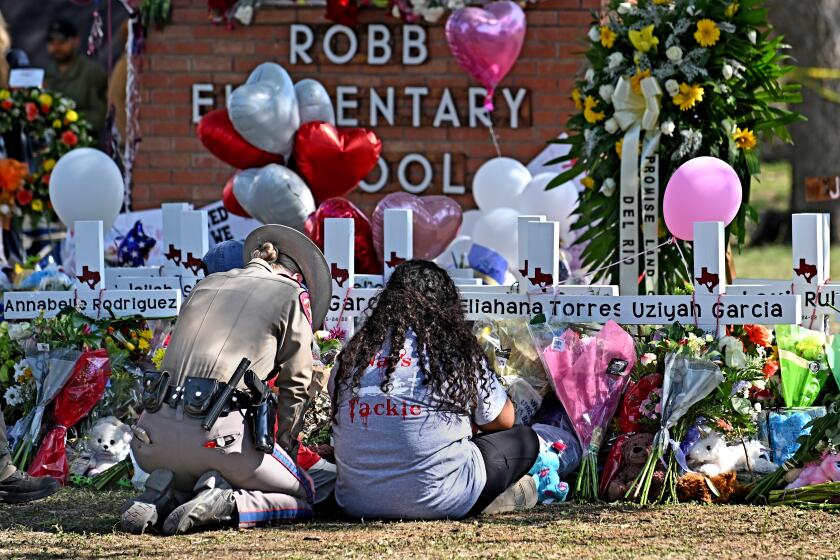

Now, as the nation mourns the Uvalde school shooting, where 19 children and two teachers were killed by a gunman in a classroom last month, some people believe an “Emmett Till moment” could change the course of the country’s gun control debate, by illustrating the bloody and deadly impact of firearms.

A gunman killed 19 children and two adults at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, about 80 miles west of San Antonio, on May 24, 2022.

The idea of communities and lawmakers seeing gruesome photos or videos of the dead children has raised questions about whether it might bolster long-awaited traction on gun control measures at state and federal levels.

But opponents of the tactic say it could intensify the trauma of grieving families or fuel misinformation and disinformation campaigns such as when InfoWars founder Alex Jones called the 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., a hoax.

Gordon, who is also president of the Mamie Till Mobley Foundation, has heard the arguments, but said she doesn’t know if showing images of gunned-down children would change people’s minds on gun control.

“I don’t think that opening the casket today, in this time, would have had the same effect that it had 67 years ago,” Gordon said. “The world can see everything now. It’s on social media, it’s on international news, so everybody is very aware and can see firsthand what is actually going on.”

Two years ago, when Gordon first saw the video of Floyd fighting to breathe in Minneapolis, she was unable to escape it because television stations kept replaying the footage of him dying.

“I had to close my eyes and just turn the channel, and my heart went out for his family that had to be subjected to that every single day on the hour,” Gordon said. “You can’t shield the youth, the young children, from it because they have access to it. ... I think maybe you do become, in order to survive, maybe you do become a little bit desensitized.”

After the Uvalde shooting, David Boardman, dean of the Klein College of Media and Communication at Temple University in Philadelphia and former executive editor and senior vice president of The Seattle Times, said this is the time for newsrooms to consider publishing the graphic photos. He said seeing the children’s smiling faces, learning details about them and watching interviews of grieving families have allowed too much distance from “the horrendous reality” of gun violence.

“I can’t imagine that most Americans would look at a photograph ... [of] the damage that an assault weapon does to a child’s body, and then not be horrified,” he said. “I refuse to believe that people are that desensitized.”

Boardman said Darnella Frazier’s cellphone video of Floyd dying under the knee of a police officer showed “the power of actually visually witnessing the reality” of police misconduct. And the emotional sacrifice Emmett’s mother made to release photos from his funeral not only raised public awareness, but was also “a real testament to her courage.”

Yet Boardman often took a more conservative approach when he was leading a newsroom; he was cautious about retraumatizing victims’ families and other victims of violence.

If he were in a newsroom today, Boardman said he would be “really careful and deliberate” by waiting to ask families for such photos, obtaining their permission and having a thorough discussion with them about the potential impacts.

As the Uvalde families began burying their slain children, most opted for open caskets, with no visible injuries showing, or adorned the closed caskets — custom-made for each shooting victim — with photos from their children’s lives.

“If we’re dependent on something as sensitive as viewing the remains of dead children to be better, that in and of itself speaks to I think an absence of sensitivity on the part of society,” said Benjamin Saulsberry, public engagement director for the Emmett Till Interpretive Center, a Mississippi organization focused on promoting racial justice and educating people on the history of Emmett’s death.

The Senate passes a bill to award the Congressional Gold Medal posthumously to Emmett Till, the Chicago teenager killed by white supremacists in the 1950s, and his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley.

It’s “admirable” that people look to Mobley’s legacy, but given the years since Emmett’s photo was released “it’s easy” for people to look at books, shows or other sources without weighing the nuances of her decision, Saulsberry said. He noted it’s important for people to not tell families how to mourn or channel their own grief, regardless of the circumstances.

“We have to be careful not to look at the tragedy that folks have faced in times past and look at how they coped and survived to then say, ‘well, the answer to this is to do what they did,’” Saulsberry said.

Wheeler Parker Jr., Emmett’s cousin and the last living eyewitness to his kidnapping, said he agreed with Mobley’s decision to release Emmett’s photo, but noted that the image did not effect change right away. For decades afterward, he said people believed Emmett “got what he deserved.”

He said while “we need something done in America to shock or get the fire in our belly about the gun problem” he’s unsure if releasing graphic photos of the children would be an effective solution, though he wouldn’t be opposed to the idea. The problem he said, is “America was founded on violence, and it’s hard to get away from that.”

Parker pointed to visiting Washington, D.C., in March to watch President Biden sign the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act, a version of the bill that took more than 100 years and 200 failed attempts for Congress to pass.

“One thing I learned, you’ve got to have a lot of patience,” Parker said. “You got to persevere and you got to have tenacity to get things changed.”

Congress has passed legislation to make lynching a federal hate crime. The Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act now goes to President Biden to sign into law.

Shocking people with the release of graphic photos won’t necessarily create change, said Mark Barden, whose son Daniel was one of the 20 children killed during the Sandy Hook shooting.

Showing the photos may inspire people to commit violent acts based on the grotesque imagery, said Barden, who is co-founder and managing director of Sandy Hook Promise, an organization focused on preventing violence and training schools and communities about issues like social isolation and suicide prevention.

“I just think that folks are desperate to try to do something, anything they can to stop this shooting epidemic that we are suffering in this country, and I think they’re just trying to grasp at anything that might move the needle,” he said.

After his son was shot to death, the only time he thought about releasing the photos was when families began lobbying the state Legislature to shield the pictures from the public record. In 2015, then Connecticut Gov. Daniel P. Malloy signed a bill exempting photographs, film, video and other images of homicide victims from being part of public records law.

“I can’t risk the toll of the lifelong damage that could possibly represent for everyone, but first especially for my personal family and for Daniel’s siblings,” he said. “I just feel like, if anyone did release photographic evidence like that, would we still be saying ‘if that didn’t do it, what will?’”

When considering how Emmett’s name has been connected to what happened to the Uvalde shooting victims, it’s important to emphasize how his mother came to the decision, said Dr. Denese Shervington, chair of psychiatry and behavioral medicine at Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science in Willowbrook.

She said Emmett being mentioned is unsurprising because Mobley’s willingness to allow people to see her grief and how her son died has stayed with people over decades.

Shervington said releasing images of violence may harm children’s mental health, causing potential sleeplessness, anxiousness, depression or becoming withdrawn. But if any shooting victims’ families make a decision like Mobley’s, people should not necessarily look away, she said. In this case, part of people taking care of themselves is “emotionally feeling” the impact of mass shootings and “letting that emotion take us to where we need to go.”

“There’s a lot of avoidance of feelings in this culture; we just move on, we don’t hang in our pain, we take drugs to relieve it, we never really sit with suffering,” Shervington said. “Maybe this is a time for us, collectively, to see this as a collective trauma in our culture, and to sit with the pain of it, and then let that pain work through us and move us into action.”

Gordon — who then lived in the same house with her family, Emmett and Mobley — was 7 years old when Emmett died. It was her family’s first experience with death. Her parents and Mobley shielded her from what was going on, even though she knew something bad had happened to Emmett, she said. She wasn’t allowed to go to his funeral.

“We were already frightened and thinking that the white people was gonna come and get us and kill us,” Gordon recalled. “We were children; we didn’t really understand the dynamics of it but as we got older, we started to relate and understand.”

For the record:

9:32 p.m. June 9, 2022An earlier version of this article said Mamie Till Mobley recalled being frightened. It was Ollie Gordon who recalled being frightened.

Gordon did not see the image of Emmett’s battered face until she was in eighth grade and remembers it now as “grotesque and disturbing.” She happened to see it while trying to give a school report and broke down sobbing in class.

She’s glad Mobley allowed the photos of him to be released, because it helped more people to understand the violence Black people were facing and to join the fight for civil rights. But Gordon says the image of Emmett’s face still weighs on her.

“It did have a devastating effect on me,” Gordon admits. “Even now, when I see things and hear things, it still brings tears to my eyes.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.