Column: Thirty years later, does commemorating L.A. riots help heal old wounds or reopen them?

- Share via

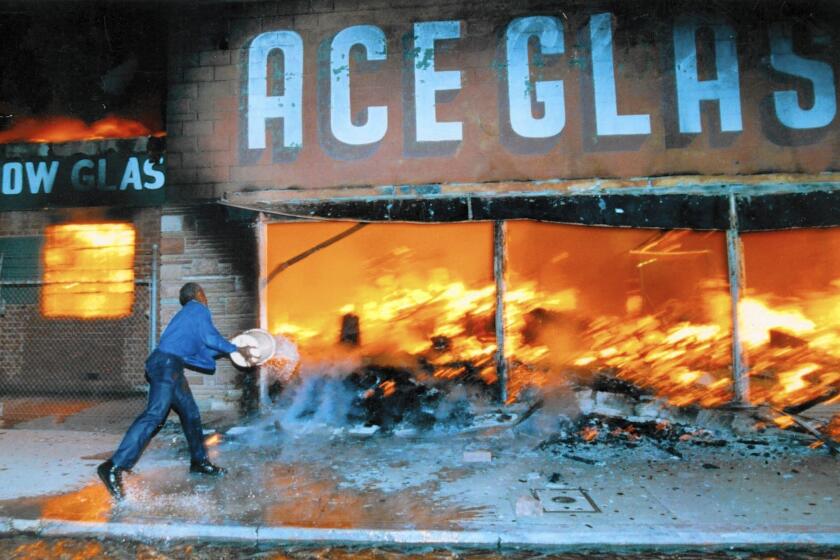

Thirty years ago today, on the second day of rioting, I made my way through South Los Angeles streets littered with broken glass and lined by the smoldering ruins of burned-out shops. I was mourning the losses, but also marveling at the ingenuity of young Black men turned street vendors overnight.

On streets choked with smoke, they were already peddling T-shirts as souvenirs. I forked over $10 for the version with a Black fist rising from a mass of orange flames. In giant letters, it declared NO JUSTICE, NO PEACE.

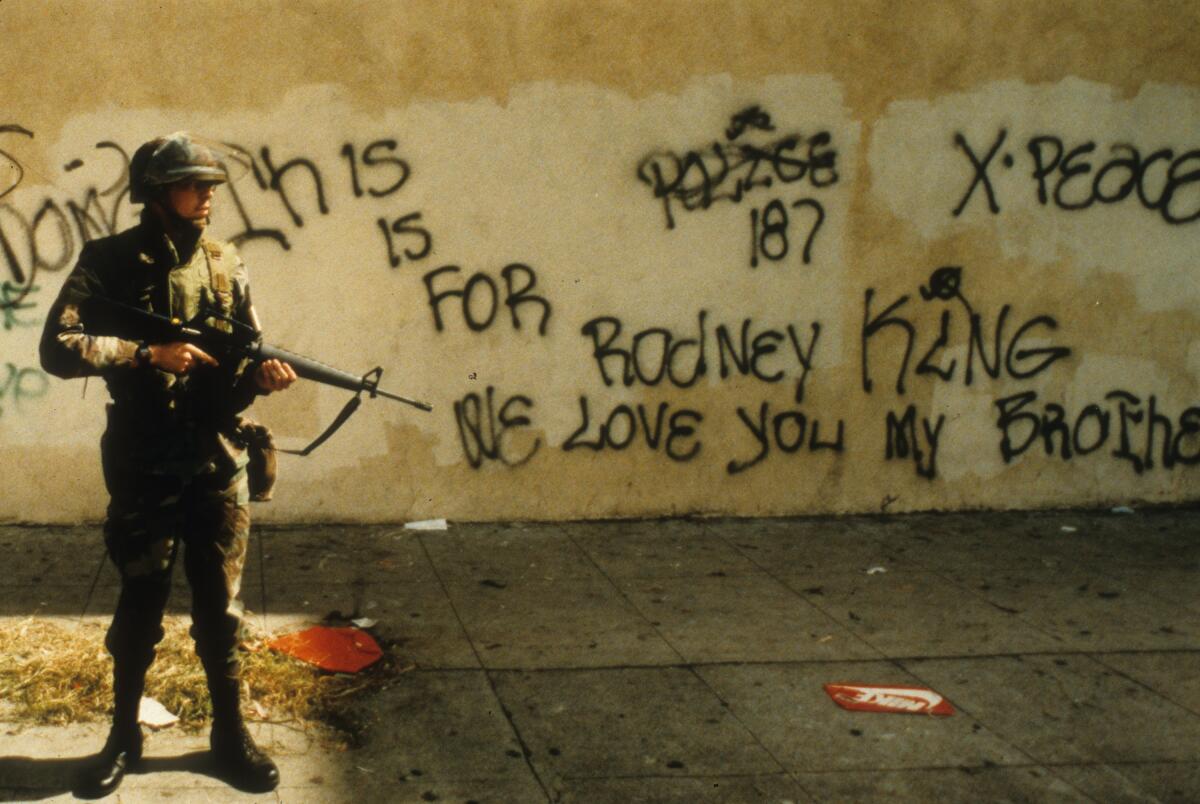

I was there as a reporter, covering the devastation after four Los Angeles police officers were acquitted in the beating of Rodney King, so I took it all in. But, worried that my emotions might override my impartiality, I refrained from interviewing anyone that afternoon.

The scene was unsettling in ways I hadn’t expected. I was shocked and appalled by the carnage — and disturbed by my own faint satisfaction that vengeance had been duly delivered.

What I failed to consider back then, in those heady days of riot slogans and raised fists, was that no matter how connected I felt to the inner-city soul of Black Los Angeles, I was going to finish my tour and head back home to my Black family in Northridge, where the only sign of the civil unrest was the smoke floating our way from over the hill.

Our grocery stores were open, liquor stores untouched. I didn’t have to keep my children inside, or worry that my clothes were reduced to ashes because the local dry cleaner had been torched.

It was privilege, not solidarity, that allowed me to assign some noble symbolic meaning to the devastation of an already struggling community. When I consider my outlook back then, I feel a bit embarrassed by my arrogance.

The truth is that during that racially tumultuous era — from the 1991 killing of Black teenager Latasha Harlins by a Korean liquor store owner to the acquittal of the LAPD officers who brutalized King and the uprising that sparked — there was nothing tidy about my role, my identity and my feelings as a Black woman and a journalist.

I didn’t know then that I’d have to revisit that cauldron of competing emotions every several years, as The Times’ newsroom compiled our obligatory riot anniversary series.

It’s a long-standing media ritual, this looking back at seminal events, from a pedestal built on all we’ve learned over time. At its best, it’s a purveyor of fresh lessons and a reminder of how far we have come. It can recast old images and inspire new generations.

But it’s also the sort of bloodletting that can reopen healed wounds and resurface buried stains — for journalists and for our readers.

***

That was the complaint I heard this week from Rodnell Harris, a Black man who watched the 1992 Los Angeles riots unfold as a child living in a Chicago public housing project.

The scenes on the television screen left the 7-year-old conflicted and confused: A Black man beaten by a mob of police officers. Entire neighborhoods in flames. Stores ransacked as police officers stood idly by.

It would take years for Harris to make the connection between the violence in L.A. and the injustices he witnessed in his own Black community back then.

Today Harris is a California resident; he moved to San Bernardino last year. And he’s still conflicted on this 30th riot anniversary about whether to honor or ignore the milestone.

Why, he wonders, do we still need to revisit such an ugly and painful episode. “It highlights the culture in a negative light, and the shame of the Black community is going to be out in the forefront,” Harris said.

This flood of attention feels to him like one more way to demonize Black people and convey the sense that nothing has changed. And if you look at the stats from South L.A., that notion may seem accurate. On measures of income, education, housing standards and employment status, the area still lags far behind more prosperous parts of the city.

Read our full coverage of the 30th anniversary of the L.A. riots.

But the protests, pillaging and violent upheaval did usher in a new era of community empowerment and accountability — and that is still paying dividends.

There are fewer liquor stores and more affordable housing for senior citizens, much of it sponsored by churches. The fires accomplished what years of community complaints and protests couldn’t.

The levels of gang violence dropped precipitously, after four of Watts’ most lethal street gangs negotiated a peace treaty, and vowed to challenge police brutality and reduce violence in their communities. The truce didn’t last, but their role as peacekeepers has. Now the city has a corps of former gang members working as interventionists to help keep the lid on gang-related crime.

And the entire city benefited from the spotlight cast on the LAPD’s endemic racism, corruption and ineptitude. The investigation that followed the riots helped fuel a law enforcement shift from battering rams and clandestine beatings to partnerships, community policing and an unprecedented level of civilian oversight.

You can argue that the riot delivered a Pyrrhic victory, one that took more from the community than it returned. After all, 63 people were killed and the region suffered a billion dollars in losses. But I remember the mindset back then. And I doubt that those changes would have been made without the uprising’s violent muscle-flexing.

The riots spotlighted for the world the rage of people stuck in a system that considered them insignificant. South Los Angeles had to scream before anyone would pay attention.

***

I’ve spent years refusing to judge the people who took to the streets. I understand their feelings of being perpetually unheard and unseen.

But I realize now, looking back, that I did subconsciously acquiesce to the tidy labels that coverage and commentary supplied: the Blacks were violent rioters, the Latinos impoverished looters, and the Koreans who lost their livelihoods were either victims or villains, depending on your perspective.

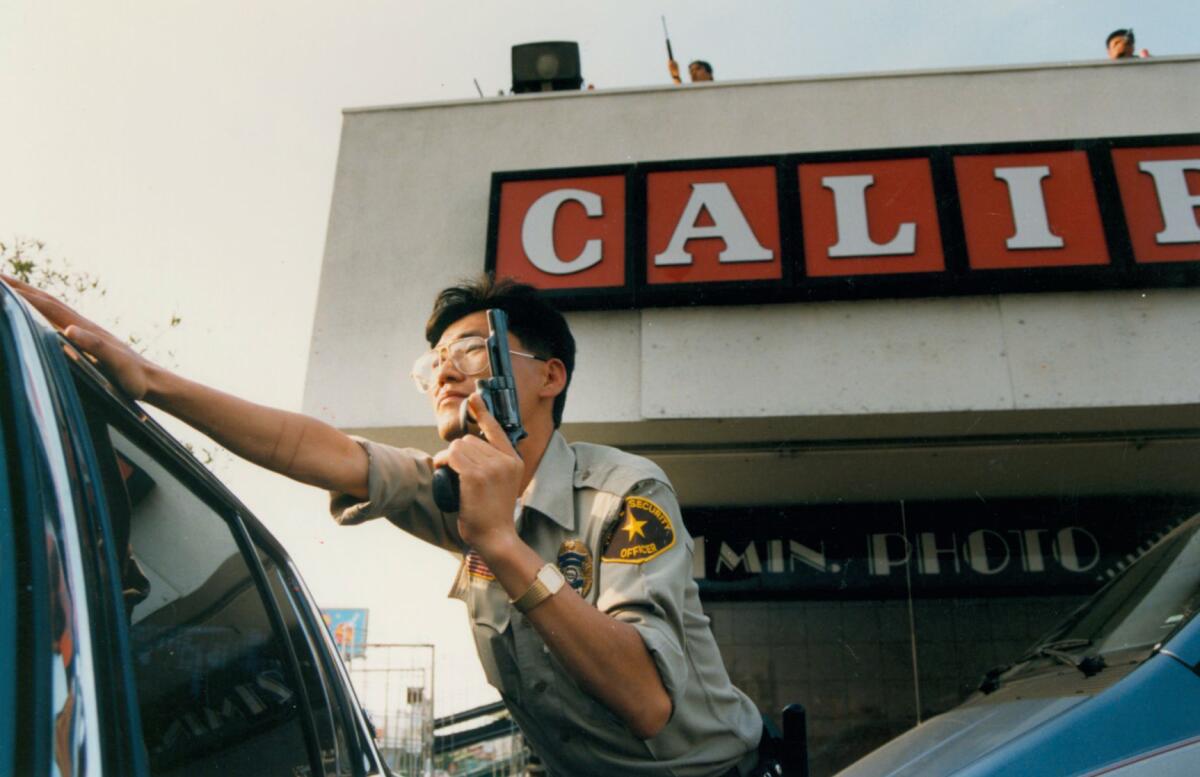

The Black-Korean conflict was an enduring storyline during the violence that erupted in 1992 after four Los Angeles police officers were acquitted in the beating of Rodney King. It was a palatable narrative of racial conflict in which white racism was not directly implicated.

They became categories, not people; providing us on the outside with the emotional distance to not feel too deeply for their individual tragedies. To me, the Koreans were collateral damage, the unfortunate victims in a long-playing drama that predated their presence by decades.

That began to change for me 10 years ago, when I met Dr. Man Chul Cho, a Korean psychiatrist who had been quietly counseling Korean riot victims for 20 years.

In Los Angeles and beyond, there’s a long history of inner-city commerce being run by outsiders, who know little about the community and are apt to treat local residents rudely. In the 1965 Watts riots, Jewish shopkeepers were targets, in much the same way as Koreans in 1992.

The “others’’ are the enemies — unless you begin to listen to their stories and internalize their suffering. Many are still traumatized, suffering from the same kind of PTSD that Dr. Cho treated as a military doctor in Korea.

Christine Oh was a high school senior when her parents’ small clothing store in a South L.A. swap meet was wiped out by looters. The business was not just their livelihood, but a family project; she and her two siblings spent every weekend there.

Her immigrant parents were devastated and bewildered. “Without understanding the historical context of the new country they were living in, they couldn’t make sense of what happened to them,” Oh said. “They were just trying to take care of their family. They’d sunk their life savings into this.”

Her father, she said, was never the same again. “The stress of what happened triggered seizures … and he wasn’t able to work,” she said. “Mentally, he just couldn’t take it.” In the silence on the line, I could hear her crying. She was remembering the sense of helplessness she felt.

She was reluctant to reach out to anyone, “because the climate was not good for immigrant business owners.” Riot victims felt like pariahs.

Latinos played a bigger role in the riots than we care to remember. Latinos were killers and the killed, assaulters and assaulted, looters and looted.

And then there are men like James Kim, who owned a liquor store at Pico and Normandie for 15 years. He can still narrate in excruciating detail his frightening faceoff with two armed men on the first night of the riots, as his wife and two children cowered in the aisles and an angry crowd converged outside.

As soon as Kim secured his store, he headed for a gun shop to arm himself. He bought a bullet-proof vest and an assault rifle. “I was so scared,” he said, “I bought the biggest gun I could find.” He didn’t have to use it, and his store was not destroyed, he said, but the fear he felt has never subsided, despite years of therapy. The riot stole his sense of security.

He doesn’t blame “the Black people,” he said. But he is still mad at the police. “They didn’t help us; they ran away,” he told me. “They protected Hollywood and Beverly Hills. They left us on our own.”

As I listened to their stories in Dr. Cho’s Koreatown office last week, a light bulb switched on — illuminating my own family’s history as outsiders, at the mercy of authorities. My father had a barbershop in a rough part of Cleveland; he had to carry a gun because he knew, as a Black man, he couldn’t count on the police.

It took me 30 years of revisiting the riots to see the similarities. It had never occurred to me to challenge the notion that Blacks and Koreans were unwitting enemies.

Now I see us as two groups at the bottom of that era’s social hierarchy — betrayed similarly by a criminal justice system that didn’t consider us worthy of protection, that abandoned us when we needed them. And we are still shouldering the consequences of that victimhood.

I’d like to imagine a world where we could be allies; maybe the George Floyd protests can become a blueprint for that. But for now I’ll take this one small win in my search for a ray of hope in the riot residue.

Maybe there is value after all in a ritual I have become weary of. Decade after decade, layer after layer, exhaustion sets in, then suddenly clarity delivers new insights.

I’d intended to declare this the final riot anniversary column I will ever write. But maybe revisiting what we’ve been through — shedding the shame and sharing our fears — isn’t the source of our miseries but a way of processing what we feel, and a route to the path that will help us heal.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.