Antisemitism has a long history in Los Angeles

- Share via

A synagogue moves its services out of its temple “out of an abundance of caution.” Another synagogue, a restaurant, a Christian church and government property are violated with swastikas and Nazi iron crosses. An elderly Jewish man walking to services with his wife in Beverly Hills is attacked and beaten with a belt. An antisemitic group delivers Hitler salutes above hate banners they’ve managed to hang above the 405 Freeway. And this week, a mass email made bomb threats against more than 90 synagogues statewide, in what law enforcement later concluded was a hoax.

“A tsunami” of hate, is how Jeffrey Abrams of the Anti-Defamation League summed up these last few months in Los Angeles.

Is the antisemitism here today worse than it has ever been?

Hard to say, because for so very long, almost no one wanted to talk openly about it — certainly not most of the people committing it, and maybe not even the people who were its victims, fearful that bringing it up would only bring them more hateful attention.

In the early 20th century, The Times regularly tut-tutted over antisemitism abroad, and deplored the pogroms that the Russian czar waged. But antisemitism here, in L.A.? Surely not — why, antisemitism is uncivilized, and L.A. was a civilized town.

Yet it was here, in places small and large. It often wore pinstriped suits; Jews regularly saw the backs of them if they had the nerve to try to get admitted to certain clubs, fraternities, neighborhoods, and inner, upper business circles.

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

It sounds much like the run-of-the-mill institutional antisemitism of the age, but what makes it stranger is that Jews helped to launch modern Los Angeles. Their names were, notably, Frankfort and Goodman, Lazard, Newmark and Hellman. Harriet Newmark and Marc Meyer’s son Eugene, born in Los Angeles, grew up and bought the Washington Post, and their granddaughter, Katharine Graham, later owned and ran it.

They held public office, created and financed some of the city’s significant institutions and projects, and deserve to be numbered among the modern founding fathers of L.A. In 1888, some of them were original members of the city’s most prestigious private men’s organization, the California Club. But in a generation or two, their sons and grandsons would not be allowed to join.

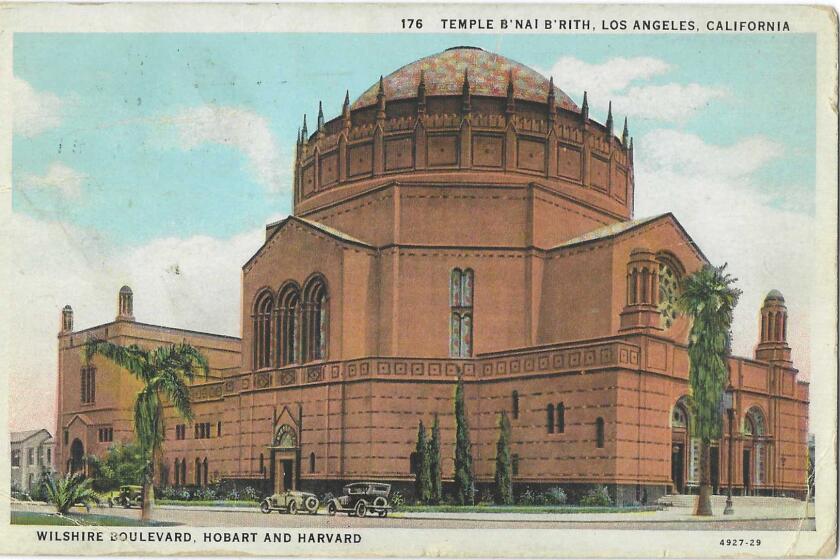

That was the 1920s, when antisemitism became more entrenched and codified here. Steve Ross is the USC history professor whose book “Hitler in Los Angeles: How Jews Foiled Nazi Plots Against Hollywood and America” was a Pulitzer finalist.

In the 1920s, the walls went up. Ross fleshed out the nature of the 1920s for me — an era of rising suspicion of foreigners, immigrants and Jews. Henry Ford gave voice to the sinister forgery “The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.” The KKK was enjoying a national resurgence. The Klan took over the Anaheim City Council in the 1924 election and had chapters in Glendale and Inglewood, where “gentlemen’s agreements” kept Jews from buying homes or joining social groups, as happened elsewhere in Southern California to “members of the Hebrew race.” Jews kept a lower civic profile, taking part in civic life not very often as candidates but as appointed judges.

Since the first Jews were counted in L.A.’s census of 1850, Jewish contributions to the city’s institutions and development have been numerous.

With Hollywood here in the L.A. city limits, antisemitism had a particular local tinge. Obviously, that didn’t affect the working-class Jews whose ranks filled the prosperous garment industry and its unions, but Jews also meant Hollywood, and Hollywood — as California historian Kevin Starr wrote — was regarded by the new masters of L.A. as vulgar.

The antisemitic snobbery extended to the golf links. In 1920, Los Angeles Jews, rejected by other country clubs, began their own, Hillcrest, which became not just a place for socializing and tee shots but for organizing and raising money for Jewish causes. In time, the greatest Hollywood moguls and actors were Hillcrest members.

Ross directed me to a Kevin Starr anecdote, and knowing Kevin as a friend, I expect it amused him greatly to write that one of Hillcrest’s members was the gangster Bugsy Siegel, who kept his membership until about 1940, when he was either given the boot or asked to resign. The Times’ magnificent sports columnist Jim Murray wrote years later that it was because the club managers “couldn’t be sure those were clubs his associates had in their bags.”

The 1930s

As Adolf Hitler was making a genocidal science of antisemitism in the 1930s, his cadre of American sympathizers were not loath to trumpet the same sentiments.

1935: On two different days in September, at about the same time that the Nazis were introducing the Nuremberg race laws in Germany, a Los Angeles fascist group calling itself the American National Party pulled off an ugly feat: It managed to slip copies of an antisemitic “proclamation” into home-delivered copies of the Los Angeles Times.

Its more anodyne exhortations told readers to “Buy Gentile! Employ Gentiles! Vote Gentile!” and slandered Jewish business practices, especially in Hollywood. ”Your dime spent at the movies may endorse and support further Jewish attacks upon our Christian morality.” You can read its more repugnant passages — and you should, to better understand the persistence of antisemitism — in Cal State Northridge’s archives.

Thousands were put up around Los Angeles County. The Monrovia News-Post reported that Pasadena police had torn down posters whose spirit “is precisely that which has earned the Hitler regime the contempt of the world … [for] a chapter of brutality that in itself is an indictment of civilization.”

How did these fliers find their way into copies of The Times? Within a few days, the paper ran a front-page warning concerning complaints about “anti-Jewish literature of a highly inflammatory and objectionable character” that were “surreptitiously inserted” after the papers left the hands of “Times’ agents, and without their knowledge.” The paper was offering a $10 reward for the apprehension of whoever did it.

A week later, the Los Angeles Illustrated Daily News headlined “Times Victim of Anti-Semitic Conspiracy.” It named the culprit as the leader of the local Silver Shirts fascist group, who was a former printer and a former Times employee, who “engineered [the fliers’] distribution folded in home editions of The Times,” and said that police were investigating The Times’ mechanical department.

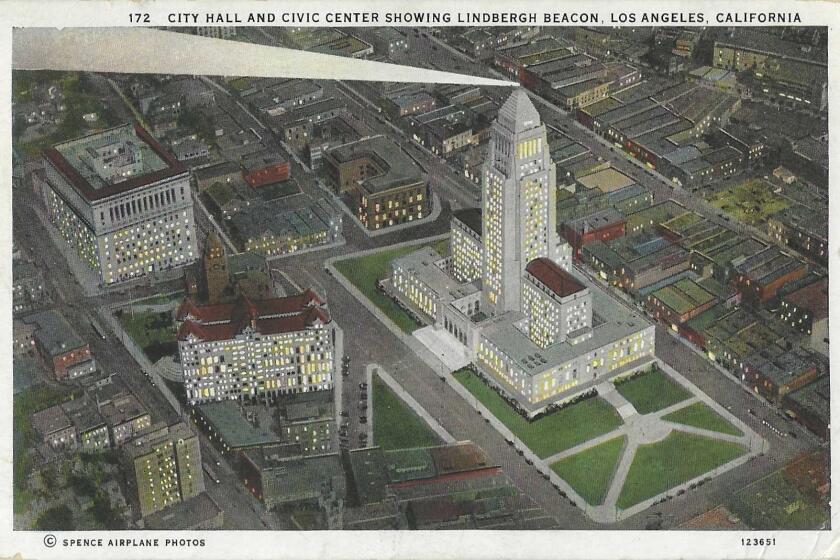

Los Angeles’ first documented smog attack — yes, we had smog attacks — was in 1943. We’ve been fighting the sources of pollution and the quirks of geography that trap it ever since.

1939: At least 10,000 antisemitic handbills were confiscated at a pro-Nazi “costume ball,” the night before they were to have been distributed, and five German American “Bund” leaders were arrested. One set of fliers was printed up with the usual canards, like calling on “Christian vigilantes” to “arise,” calling Hollywood “the Sodom and Gomorrha” (misspelled). It bore caricatured drawings — you can see it here on Truthdig — and evoked slimy stereotypes about Jewish men and ”young Gentile girls.” In a “false flag” attempt, another set of fliers purportedly created by Jews used the same incendiary language against Gentiles: “Make the United States a Jewish nation … make a mass attack upon the insolence of non-Jews in this democracy … Gentiles are not human beings, but beasts.” This same group had already managed to get to the top floor of a downtown department store and toss handbills out into the street below.

1939: Nine swastikas were painted on the doors and sidewalks of a Mid-City temple, and police believed it to be the work of the same vandals who did the same at a nearby temple the month before. “Heil Hitler” was daubed on the tabernacle’s front steps.

Once the U.S. entered the war against the head hater of Jews, antisemitism in any guise, from goose-stepping on the home front to “gentlemanly” prejudice, was unseemly.

After World War II

But a resurgence of antisemitism, institutional and individual, was only delayed, not derailed. It would return in the 1960s, ‘70s, ‘80s, ‘90s. We’re seeing it again now, of course. That’s the thing about antisemitism — it never really goes away.

1960: California Atty. Gen. Stanley Mosk asked a grand jury to look into suggestions of an organized conspiracy to drive Jewish residents out of the resort town of Elsinore.

1962: As two Protestant clergymen were speaking at a Jewish temple on the topic of “the radical right,” their homes were bombed. Also as they were speaking, members of an antisemitic group stood outside the temple pushing onto passersby leaflets describing Jews as enemies of the country, no better than Communists and the United Nations. LAPD Chief William H. Parker blamed the bombings on — gee whiz — antisemitism.

1962: San Francisco’s Anti-Defamation League concluded that half of the state’s clubs locked out Jews, and that L.A. has a “particularly high volume of employment discrimination against Jews,” especially in the fields of insurance, banking, oil, real estate and department stores, which is paradoxical, considering that many of them were founded by Jewish merchants.

1965: Around Passover, three Tustin Jews found burning crosses on their lawns; the Orange County sheriff’s juvenile bureau investigated on the presumption that it was kids, not extremists. It was the latest incident since a Jewish temple moved to Tustin from Santa Ana; the year before, the temple got three bomb threats, and someone broke out windows in the new building.

1969: Ten years after L.A. Jewish leaders launched a “moral persuasion” campaign to open the city’s corporate and social bastions, and seven years after UCLA sociologist Reed M. Powell began a study of the institutional resistance to Jews, Powell concluded that no matter how qualified he is [this is still very much a man’s world], the Jew “knocks in vain” for admission. It’s a vicious circle: A man can’t get into a club because he’s Jewish, and not belonging to the club cuts him out of the big promotions. (In time, we’d realize the same thing was true of Black people and women.)

1976: A Woodland Hills Jewish family discovers a cross burned into their front lawn with flaming gasoline. They called police about it after hearing news stories of a wooden cross burned at the home of a Black family in Reseda. A month before in Granada Hills, a fire started in a house one day before a Black family was set to move in.

1981: Throughout the Fairfax district, Nazi slogans were spray-painted on Jewish-owned businesses and apartment buildings, and antisemitic handbills left behind by a Nazi-inspired “white people’s party” threatened Jews with “death and destruction … your stores will burn and your churches will be blown up and your people will die! Beware!” Posters were signed by the “new fuhrer of the new reich.” At a photo shop exhibiting a picture of Barbra Streisand, a swastika and the word “Jew” were painted on the window. Unsettlingly, this was only the latest and worst in several weeks of antisemitic vandalism.

1982: A 3-foot-tall red swastika was painted on the wall of a Torrance deli and restaurant run by a Jewish woman. Two weeks later, the place was bombed. Police and fire investigators were inclined to believe the attack was “something personal,” not “part of an anti-Semitic attack.” Torrance was also home to a holocaust denial group that offered $50,000 for proof that any Jew was gassed to death at Auschwitz; it lost the case in a notorious lawsuit the year before. The “moral persuasion” campaign idea still had currency; after many of these incidents, some rabbis and community leaders soft-pedaled in public; “Why should I say one miserable bombing is a reflection of the South Bay community?” one rabbi asked after the Torrance incident.

1985: Jewish Defense League members patrolled neighborhoods in Van Nuys after a Hebrew school was burglarized and “kill Jews” was written on school walls, and after a Panorama City family found signs reading “Russian pigs” and “Hitler was right” on one of their trees, and swastikas burned into their lawn.

1986: In North Hollywood, homes and schools were defaced with slogans like “Jew Die” and “A good Jew is a dead Jew.”

Cal Worthington (and his ‘dog’ Spot), ‘Madman’ Muntz and other colorful local pitchmen used to claim space in the public consciousness. Our culture may no longer be built for that brand of commercial antics.

The long view

Jacob Frankfort was the first Jew known to live in L.A., when he arrived here in 1841; more than 180 years later, Los Angeles is home to the second-largest Jewish community in the nation, and a diverse one, with Jews from the world over.

Zev Yaroslavsky, a former L.A. City Council member and county supervisor, was born here, to Russian Jewish immigrant parents. Maybe the sheer numbers of L.A.’s Jewish community gave a sense of critical mass, and maybe even a sense of security.

“We lived a sheltered life, because most of the people in the neighborhood were Jewish. Growing up, the only overt antisemitism I knew of was against my classmates at Fairfax High (which was 90% Jewish) who played on the football team and who were targeted with anti-Jewish epithets from players from schools that had few if any Jews, like one Westside high school. We all knew about this, but it was viewed more as bullying than prejudice, although sometimes that was a distinction without a difference.”

That was in the 1960s, and so was this incident which managed to make a point about the idiocy of antisemitism by using the sharpened point of humor: Groucho Marx, the vaudevillian, actor and indefatigable wit, had inquired about a membership at a restricted country club — “restricted” was the genteel word for “no Jews allowed.” (That Black people were not allowed went without saying.)

He was told that the club would make an exception for him, as long as he didn’t use the pool. Groucho’s comeback: “My daughter’s only half-Jewish. Can she go in up to her knees?”

Los Angeles is a big, complicated place. Patt Morrison explaining how it works, its history and its culture in Explaining L.A. on latimes.com.

More to Read

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.