Why doesn’t L.A. have piles of garbage everywhere? Many years of fighting

- Share via

It was war to the knife at Los Angeles City Hall in the 1950s and ’60s. Official L.A. was flinging around insults like “pathological liar” and “dictator” and “unholy alliance.”

The vicious debates were over what we now call recycling, but what was then called, in tone-deaf fashion, “segregation,” separating recyclable trash from the rest of it.

Embarrassingly, in the ’50s and ’60s, as other people in the nation were fighting the good fight for racial justice, official L.A. was waging a pitched battle over the city’s trash.

It still makes for astounding reading, and the L.A. Times had enough perspective to marvel, in March 1963, “Los Angeles is probably the only city in the nation where rubbish rates hundreds of thousands of words of newspaper copy and hundreds of hours of radio and television time.”

To this day, Southern Californians routinely divvy up their recyclables from garden bits from hopeless garbage. So it’s hard to conjure up the acid passions that went on over this, and went on for the better part of a dozen years.

Yet those passions were enough to help one man defeat an incumbent L.A. mayor, and they threatened to wipe the City Council clean of its members when the public found out that not separating trash could conceivably send a non-separator to jail for six months.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

So welcome, new state composting law — the one that requires Californians to separate organic waste from other trash and declares that cities and counties pick up organic rubbish from residents and businesses. But it leaves it to the state’s many hundreds of cities and counties to work out the details.

Ever since humans began trying to live a long way from the smell and sight of their own middens, they have also hoped that someone — these days it is civic magicians — will whisk away their unpleasant byproducts. Los Angeles, for example, almost 150 years ago took the bold step of making it illegal to leave slaughtered livestock on public sidewalks.

In 1905, a “garbage committee” led by a Mrs. J.G. McLean demanded a more subtle and sanitary L.A. trash management than the noisy and noisome practice of trash cans collected and then dropped with a clang on public sidewalks where, as The Times wrote appetizingly, they lay “with reminiscences of the day before yesterday’s dinner clinging to the sides, there to fester and fry in the fierce rays of the sun.”

Mrs. McLean was triumphant. The city agreed to commence work on a municipal incinerator, and to begin less obtrusive backdoor garbage collection by metal-lined, covered vehicles. “We asked for a crust and they gave us the whole loaf.”

In the first decade of the 20th century, the L.A. city population tripled, as did its garbage. In 1911, the city dispensed with private trash collection and took up its own routes, at least in the central city. As late as 1940, the city was collecting trash twice a week in neighborhoods with mostly homes, three times a week in apartment districts, and every night downtown, but independent companies were scooping up rubbish in the harbor, in Venice, and in the burgeoning San Fernando Valley.

What did L.A. do with it all? The arguably edible stuff got sent off to pig farms in places like Fontana and Soledad Canyon. When Los Angeles River floods washed out railroad bridges in 1938, the city was forced to dump the garbage in the river, as generations of Angelenos had already done with their trash and toxics, and hope there would be water enough to carry it all away to the ocean.

Nothing really made garbage disappear. It just got moved, ideally farther and farther from taxpayers and voters. As The Times pointed out in 1908, Santa Monica was separating out trash that we would now call recyclables, like cans and bottles, incinerating the former, and hauling the latter off “into yawning arroyos.”

And then … eureka! Cities’ permanent solution, or so they thought, was fire — nice, tidy incinerators that made trash go poof. Burg after burg built supposedly smokeless municipal burners. L.A. opened one in 1907, and soon outgrew it. Another was OKd by voters in 1947. But across L.A. County, people already torching their trash openly in their own yards started building personal incinerators.

And just like that, L.A. was living up to the name bestowed upon it in 1542 by the Spanish explorer Juan Cabrillo: “Bay of Smokes.” That smoke came from Native Americans’ fires. This smoke was from those backyard incinerators.

Moviemakers, painters and authors have long opined on the quality of L.A.’s light. A Caltech scientist illuminates on why our light is so remarkable.

Smoke doesn’t honor fences. In 1918, a week after the end of World War I, a genteel neighborhood pissing match in Pasadena wrapped up when a judge ruled against a cousin of President Woodrow Wilson’s close advisor Edward House and in favor of a scion of the Murphy petroleum fortune.

House was livid that smoke from the Murphy incinerator was covering his roses with ash, and wafting a “vile” smell into his estate. In a split decision, the judge found that “anybody may have an incinerator in his back yard to burn refuse,” but that actual burning sparks could not float away from the Murphy incinerator along with the smoke.

In 1957, in the celebrated murder case against L. Ewing Scott for killing his wife — one of the first occasions in California that anyone was convicted of murder without a corpse — the jury poked around Scott’s backyard incinerator, where investigators had found that a woman’s clothes had been burned there.

Over the years, The Times ran how-to features on building and decorating your incinerator.

A new law requires Californians to recycle food scraps and leftovers. What is composting? What can you — and can’t you — compost? We’re here to help.

In 1914, a minister in the town of Tropico — now part of Glendale — earned inky praise for an incinerator design that “may also be used as a sort of Dutch oven, for the cooking of beans, etc., and also proves valuable in the boiling of water on wash days.” In 1932, a gas station owner in Ontario got an artsy Times review for setting his incinerator in a garden planted with narcissus, geraniums and verbena, and — the crowning touch — “the smoke comes out the little chimney” made to look like “a plaster gnome with long beard, high Santa Claus cap and colorful clothing … smoking contentedly by the side of a little lake.”

By the time jurors made their trip to Scott’s Bel-Air house, Los Angeles County had just shut down all 1.5 million backyard home incinerators. Beverly Hills did so the year before, with Whittier hard on its heels. In spite of what that judge told the Pasadena elite, your personal garbage burn was everyone’s air pollution. It wasn’t the biggest smog source — even then, cars and heavy industry were getting that responsibility — but a manageable one.

The incinerators vanished. The trash didn’t.

Street furniture may not seem like one of the things that is, or should be, representative of L.A. But it’s part of the cultural and visual fabric.

And that’s where the separation battle began in earnest. Once the personal incinerators were extinguished, cities began buying and leasing more landfills. Los Angeles opened one in Toyon Canyon, in Griffith Park, which didn’t close until 1985.

L.A. voters had in 1956 opted for municipal trash collection over private services, but in 1961, desperate to slow the choke of landfills, the city ordered residents to start separating salvageable metals from the rest of their trash.

That made voters kick over the traces again. They voted out incumbent Mayor Norris Poulson and voted in Sam Yorty, a twangy-voiced Nebraskan who campaigned on the dreadful coercion of housewives forced — forced! — to separate the trash. Yorty had once had a not very successful business interest in operating and brokering trash dump sites, and Poulson dropped delicate hints about organized crime.

But Yorty’s homey appeal to those mentally overtaxed homemakers carried the day. Then Mayor Yorty turned his campaign on the City Council. It was ugly. It was angry. Two years into Yorty’s term, the public found out that not separating trash could be punished by a ridiculously harsh six months in jail or a $500 fine — the same penalty for firing up outlawed incinerators.

Yorty made the most of it. He launched a “housewives’ revolt.” Break the law, he told Angelenos. Go ahead and dump your trash into a single bin, and he would see to it that they would not be punished.

At last, in 1964, a war-weary City Council threw in the towel. One bin could rule them all. Yet council members warned that the small savings from a single-bin weekly pickup would cost more in the long run — even, perhaps, a homeowners’ fee for trash collection. “The Yorty tax,” one councilman called it.

They were right. In 1977, the city restarted a trash-separation pilot program. And in 1979 came that first-ever fee for trash pickup.

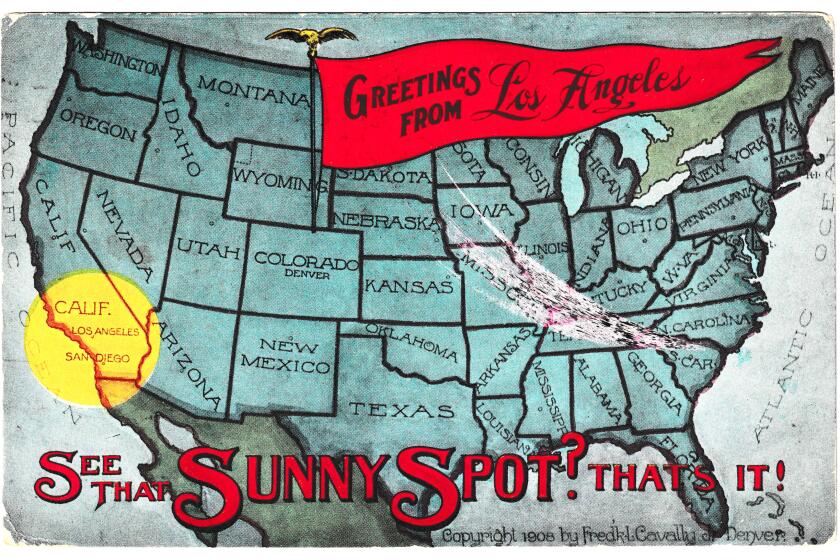

Sunny and mild L.A. winters have long been used to sell our town to frigid Midwesterners and Easterners, attracting the sick, the farmers and the moviemakers.

Like the new state composting law now, cities’ hands were forced by a 1989 state law requiring cities to cut the trash they were dumping by a quarter by 1993 and by half by the year 2000. In the L.A. Times magazine in 1991, humorist Harry Shearer recommended that a “landfill thermometer” be painted on the side of trash trucks to remind Angelenos how near to overflowing the city’s dumps were.

After all those decades of back-and-forth, Los Angeles required once and for all the separation of recyclables, as did Santa Monica, Pasadena and other cities. Mayor Tom Bradley signed the new law — declaring the 1990s the “decade of recycling” — and then obliged photographers by tossing a bin full of glass bottles into a special truck.

With the patchwork of dozens of cities in L.A. County, and the back-and-forth over curbside recycling, it takes some serious homework (and a study of the rules inside the lid of your L.A. city trash bins) to keep up with the rules.

The composting law to keep food waste out of landfills creates another patchwork. The state proposes, and the network of cities and counties disposes, literally. As the saying goes, check local listings.

Fifty and 60 years from now, as far away from the here and now as this moment is from the great trash-separation skirmish, Angelenos will think we must have had a screw loose, taking so long to send kitty litter and water bottles and food waste off to different destinations to disappear.

So head off destiny at the pass with an even crazier notion. We throw out 30% or 40% of all the food we fix. Don’t want to be bothered with composting? Clean your plate.

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.