You thought the oil spill was bad? In L.A., toxic waste is everywhere

- Share via

In a bad way, a very bad way, the Huntington Beach oil spill is the enviro-disaster equivalent of the giant panda.

The oil spill is of course many things that the hugely adorable panda is not. The oil spill is not cute. It is not charismatic. But it is the big event, the photo-compelling thing that commands news airtime and elbows into social media.

The downside of giant panda-dolatry is that it can eclipse the sorrowful state of other species who are just as critically endangered but unlikely to inspire Facebook pages and stuffed toys. When “charismatic mega-fauna” are in trouble — pandas, elephants, polar bears — people rise up. When the pygmy hog-sucking louse slides toward extinction, who but the pygmy hog cares?

Ow, what does that have to do with the oil spill?

Pandas and petroleum messes share a disaster template: big, visually compelling crises bring out volunteers and donations and legislation and politicians. But the slow, unseen toxins that have been and still are tainting land as well as sea have to go begging for attention and news coverage.

They are out there. Boy, are they out there.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

Between Los Angeles’ oil-pumping past and its half-century-plus as the factory of the world war and the Cold War, we have spilled and spread so much chemical poison into the earth beneath our freeways and our feet that by rights each of us should have two heads.

Imagine what the L.A. landscape would look like if places where the soil or water had been poisoned were flagged like the minefields of Angola, where Prince Harry recently walked along the pathways that his mother, Diana, the Princess of Wales, had before him.

In some parts of L.A., large areas would be marked with a skull-and-crossbones sign alerting you that toxic waste had been manufactured or dumped there over generations, befouling the soil, befouling the groundwater so critically that over the last few decades, the Environmental Protection Agency has clocked Superfund cleanup sites throughout California. Now, at least a dozen sites are still active in L.A. County, and many of the older ones are being cleaned up and repurposed, like the Maywood acres turned into a riverfront park.

A lot is the dregs of victory in World War II. Kansas and Iowa grew wheat and corn for the war effort; Los Angeles became the forge and anvil for knocking off the Nazis. Defense plants, metal plating plants, machine shops, real and artificial rubber manufacturers — the priority was beating the enemy, without realizing or worrying that manufacturing was creating another invisible enemy that could be just as life-threatening in the long run as a bomb or a bullet.

Ever since, manufacturing for aviation and general industry has kept L.A. booming and the nasty byproducts flowing — sometimes furtively, sometimes openly. The astonishing discoveries of the mid-20th century, the plastics and metal alloys, the insecticides and miracle drugs, also birthed chemical byproducts that weren’t so wondrous or beneficial.

For so long, if the public thought of them at all, they thought of even natural pollutants as an inconvenience, not a danger. In 1891 as the city population made the 50,000 mark, the city resisted spending money to build a line to carry sewage — “night-soil,” as it was called in deference to Victorian sensibilities — to dump in the ocean. The objection wasn’t pollution; it was the “wasteful and extravagant” cost. (Until the early 1950s, Los Angeles County was the most productive agricultural acreage in the nation, and there, too, the runoff pollution from fertilizers and pesticides took its own toxic toll.)

The L.A. River and its tributaries were the city’s unofficial trash chute. Dead animals, fertilizer runoff, old cars, industrial chemicals dumped under cover of darkness — once the rains came, anything could get washed away, and until then, well, just live with the stink and the poison.

Along La Cienega near Inglewood. At Beverly Hills High School. In people’s backyards in Echo Park. Atop Signal Hill. Oil wells are everywhere in and around L.A. You sure don’t see that in Paris (France).

The air pollution we all know about. But below is just a sampling of historic toxic sites, and again, many have been cleaned up. I am not picking on any community — the land underfoot almost anywhere in L.A. is like a chemistry set:

- In Orange County, after the war, waste from refineries was just spread over vacant land.

- In Rialto, six miles of groundwater contamination originated from a World War II weapons and ammo storage site, and thereafter, from fireworks and industrial defense manufacturing chemicals.

- Across the San Gabriel Valley, compounds like perchlorate, used in rocket fuel, and other chemicals seeped into something like 170 square miles, reaching into the aquifer serving more than a million and a half people.

- In the early 1980s, someone made money hauling thousands of barrels of the chemical waste from L.A. industries and just dropping them along a flood control channel in Santa Fe Springs, where they leaked their toxic juice into the land and the runoff water.

- Along the Pearblossom Highway, at about the same time, someone abandoned 18 barrels of the probable carcinogen PCB. Hunters shot them up and the stuff soaked 15 feet down into the desert soil. When the money to clean up the mess ran out, the crews just fenced off the area and left.

- In Torrance, for nearly 30 years beginning during the war, unlined pits and ponds were filled with waste from synthetic rubber-making and other industries, spoiling the groundwater with benzene and toluene.

- Thousands of acres of the San Fernando Valley — whose defense plants helped to win the war — made it onto the EPA’s Superfund site lists. As recently as 2018, a couple of aerospace companies were ordered to pay millions to scrub the land of contaminants, but damage to groundwater and soil is often incalculable and monstrously expensive to undo.

- A year ago, a federal bankruptcy judge shockingly allowed Exide Technologies to simply walk away from the years-long mess at its battery recycling plant in Vernon. Its legacy of lead and toxics like arsenic has reached across a half-dozen working-class, mostly Latino communities and many thousands of pieces of property. Who will pay for this? You and I will. The taxpayers will now be on the hook.

And this conflict runs like sludge through these poisoning cases: how to get the guilty companies to pay for their environmental sins? As so often happens, the profits go into private pockets; paying for the human damage from the fallout comes out of the public’s pockets.

In 1973, California started regulating where and how companies could rid themselves of hazardous waste, but the lawless midnight dumping didn’t stop. Some companies sent innocuous-looking trucks to regular landfills with toxic chemicals stashed deep inside the loads. A Northrop aircraft subsidiary was charged with smuggling 21,000 butane cigarette lighters into such a landfill; it was busted when a bulldozer ran over them and set off a flash fire. L.A.’s then-district attorney, Ira Reiner, shocked the corporate-chemical culture by filing criminal charges against illegal dumpers small and large and sending some execs to jail.

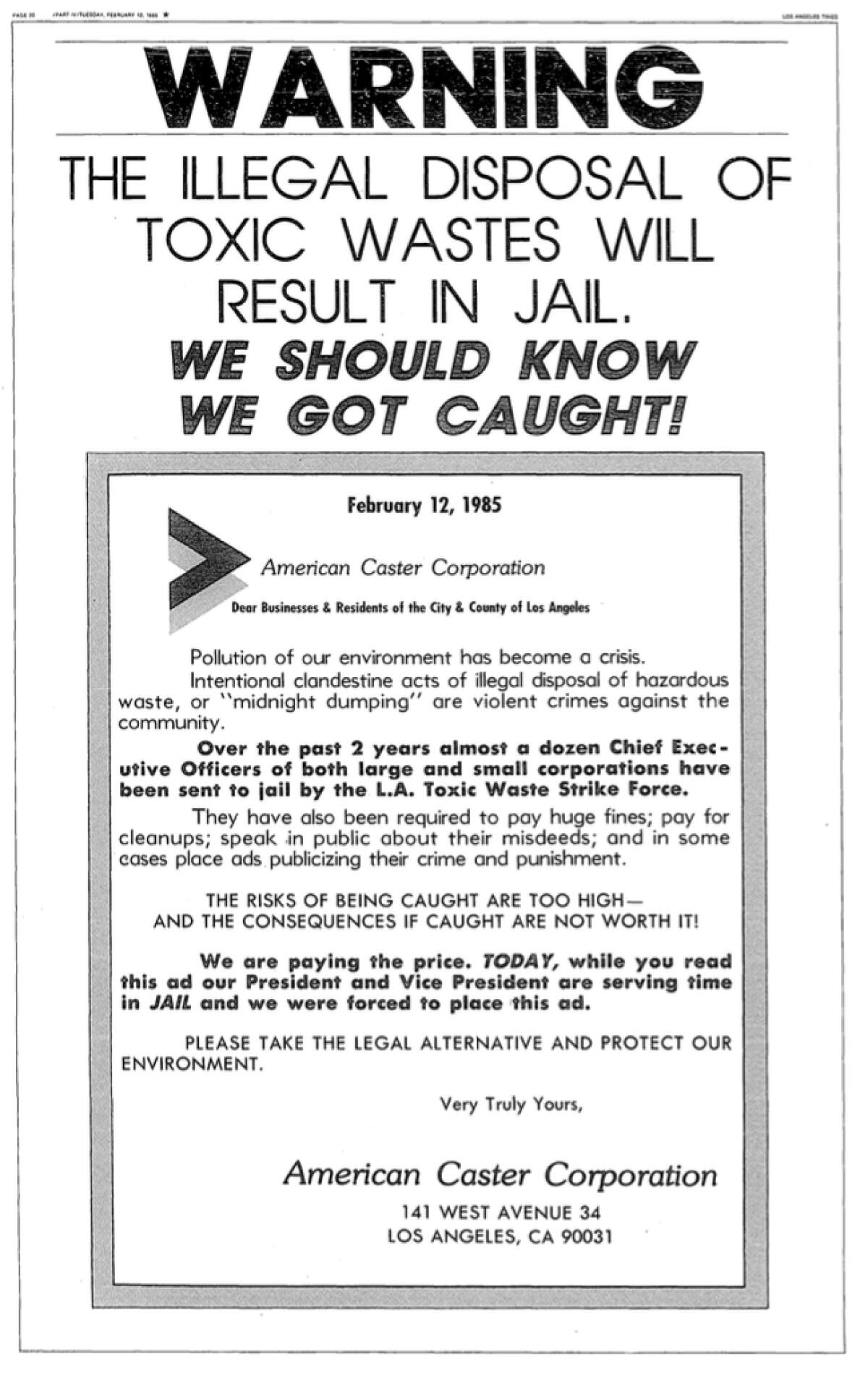

Corporate public shaming had its uses too. The president and VP of a company that made casters served jail time, and the company itself had to run a full-page Times ad confessing, “We got caught.”

At least some of that waste, you could see. Most of L.A.’s hazard heritage has been underground, out of sight. In 1985, the state had an estimated 142,000 underground storage tanks, 36,000 in L.A. County, and some of them had been seeping and leaching their chemical stew for years. Water wells in Burbank were tainted in part by buried Lockheed tanks. Enterprises you couldn’t imagine having such tanks had them: car washes, mini-malls, movie studios, dry cleaners, City Hall and the state capital.

In the early 1990s, the state had programs and deadlines to clean up leaking underground tanks at gas stations and elsewhere, but a lot of gas stations had to close down rather than pay up. A onetime gas station site in Highland Park is now a popular park where the most common vehicles are dad-powered strollers.

The boldest and most damaging toxic-dumping scheme may be this one:

Starting in 1947 and 35 years thereafter, the nation’s biggest manufacturer of the pesticide DDT, Montrose Chemical Company, was right here. In 1972, 10 years after author Rachel Carson wrote powerfully about the murderous effects of DDT on the natural world, the United States banned most of its uses.

As The Times reported, “every month in the years after World War II, thousands of barrels” from Montrose were “boated out to a site near Catalina and dumped into the deep ocean.” Toward 1971, when the dumping stopped, the dumpers sometimes didn’t bother with boats and “just dumped it closer to shore. And when the barrels were too buoyant to sink on their own, one report said, the crews simply punctured them.”

Half-a-million barrels might lie offshore between the Palos Verdes Peninsula and Catalina, but no one yet knows for sure. It has been, as The Times said, “like trying to count stars in the Milky Way.”

Should California be split into two states? Three? Six? At the very least, we’re due for another round of intrigue on an eternal question about the Golden State.

It’s an ignoble thing we’ve done to a landscape whose gorgeousness brought us here in the first place. In very short order, much of this clean and lovely place, and a shoreline whose wetlands had cleaned and revived the natural system for millennia, were turned into sodden chemical sumps.

Now let’s hear from Michael Méndez, an assistant professor at UC Irvine’s school of social ecology, and author of “Climate Change From the Streets.” The book stems from his analysis of environmental catastrophes — natural and manmade, from polluting industries to wildfires — and how they are visited most, and most invisibly, on the poor, including the immigrant labor force.

He’s studied the not-coincidental overlaps of poor neighborhoods and toxic industries like refineries, and the harm to the health of residents, a toll he calls “slow violence.” It happens when “environmental racism and injustice as political choices are being made that intentionally pollute or harm some communities and prioritize some communities over others.”

A childhood epiphany put him on this path. He grew up in the northeast San Fernando Valley, a ground zero for “environmental injustice,” with landfills, toxic properties, and grotty air quality.

His parents volunteered him for school busing to Chatsworth, where “I saw a different urban environment. I questioned at an early age why many streets in my neighborhood had toxic, noxious industries and dirt roads, and the West Valley had paved streets, nice lawns and open space.”

Neighborhoods like his are “sacrifice zones,” he says; it’s a phrase in use for at least 50 years for neighborhoods or stretches of land that have been environmentally despoiled in someone else’s interest — national defense, industrial progress, municipal or state or national dictates, corporate profits, even nuclear testing on native lands.

You can, once in a rare while, fight City Hall and win. He was inspired by the 1990 campaign by community activists against the Lopez Canyon landfill in Sylmar. It’s still leaching methane 25 years after it closed, but the city is using the methane to power gas turbines for renewable energy for 4,500 houses. “It was a wake-up call for me to see activists resist environmental inequities.”

Even before that, in 1985, L.A. planned to build a trash-burning plant about a mile east of the Los Angeles Coliseum. The prospect of pollution from “LANCER,” the “Los Angeles City Energy Recovery” project, riled up neighbors, and the city pulled its plug. That triumph showed South L.A. residents that they had the muscle and the confidence to assert their neighborhood’s interests.

One year later, 1988, a city ballot measure, Proposition O, asked voters to stop Occidental Petroleum from drilling oil in the Pacific Palisades. It won, and the company ended up donating the two acres of land to the city.

Pacific Palisades is a rich neighborhood, and the prospect of oil rigs and oil spills in its ZIP Codes helped to kill off the plan. The same could happen with offshore drilling and the Huntington Beach oil spill; if enough of the rich and offended object to more oil drilling, it might help to stop it.

“We basically have two paths to follow,” Méndez said. “We can move toward more efficient policy action similar to what happened in 1969 with the Santa Barbara spill, where you had Republicans living in that area and you had President Nixon come down and engage,” and soon you had clean water laws and the Environmental Protection Act.

The other path is like the one in the movie “Clueless.” Cher Horowitz, the Beverly Hills teenaged protagonist, organizes relief for a Pismo Beach disaster — and “her idea of activism was donating ski equipment she didn’t even want any more.”

“So are we going to focus the way we did in 1969, or are we going to be like Cher and pass on to other generations the equipment [the legacy of poison] we don’t even want any more?”

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.