California recall price tag could hit $300 million. Some say it was a waste of money

- Share via

The recall election is over, but the vote counting continues — as does debate over whether it was all worth it.

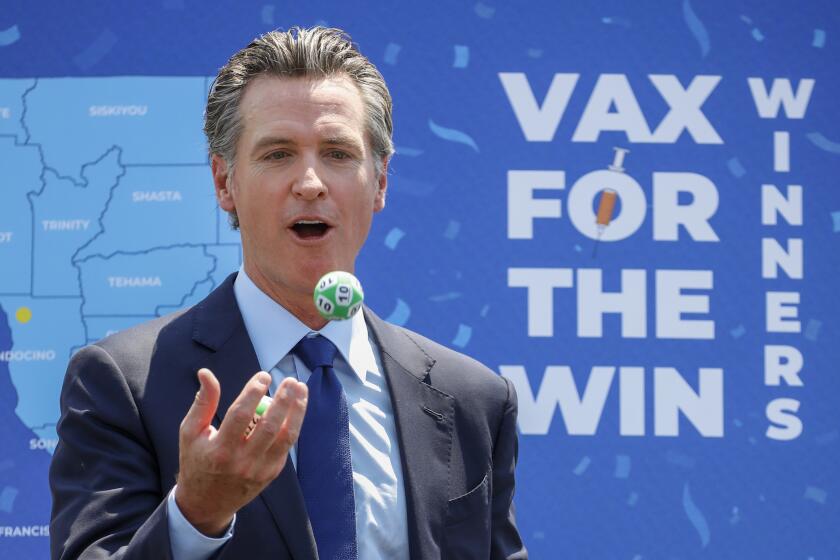

Gov. Gavin Newsom survived the recall attempt by a big margin, and that has led some to question whether the system works and if changes are needed.

On Wednesday, two state legislators said that the failed effort to remove Newsom was too costly and needlessly confusing. They called for further review.

Times columnist Steve Lopez was more blunt, asking: “Was this the most frivolous waste of time in California election history?”

Columnist George Skelton writes that Newsom’s landslide victory proved what most already knew: No Trump-supporting conservative can win statewide office in liberal-leaning California.

How much did the 2021 recall election cost?

California lawmakers agreed to spend at least $276 million in the most recent state budget to cover the costs of the recall, but some elections officials have estimated the final tab will be closer to $300 million.

What are lawmakers saying?

“That money could be spent on housing, on homelessness, on combating climate change, forest fires, early childhood education, you name it,” said Assemblyman Marc Berman (D-Menlo Park), chairman of the Assembly Elections Committee. “There’s a lot of desire, and need, for reforming the recall process.”

Times Sacramento Bureau Chief John Myers reported that Berman and his counterpart on the state Senate Elections Committee, Sen. Steve Glazer (D-Orinda), said Wednesday that they intend to launch a bipartisan effort by early next year to review the existing procedures governing statewide recalls and a number of ideas to reform the process that have been offered in recent weeks by academics and constitutional experts. Any substantive change would have to be approved by California voters in a statewide primary or general election, as early as next year.

“The voters want to see a more democratic process put in place that keeps elected officials accountable, that prevents political gamesmanship of the rules,” Glazer said during a news conference Wednesday.

Others also called for a broad review of recall election rules. Assemblyman Kevin Kiley (R-Rocklin), whose recall replacement candidacy had drawn about 160,000 votes as of Wednesday’s totals, urged the Democratic lawmakers to include scrutiny of campaign finance laws, posting on Twitter that the “quirk of unlimited campaign contributions” for the incumbent who is the subject of a recall allowed Newsom to bombard TV airwaves with ads.

Gov. Gavin Newsom survived the recall election. What can we learn from the results? The Times took a look on a county level and found some trends.

What do polls say about public feelings on recall rules?

On Monday, a poll conducted by UC Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies and co-sponsored by The Times found a majority of voters surveyed said they support several options for revising the recall rules. Of the five options the survey proposed, the largest majority of voters surveyed said they would support creating a runoff election in cases where a governor or other statewide official was recalled but no replacement candidate won a majority of votes cast.

Other potential changes mentioned in the Berkeley IGS survey included a higher threshold for candidates seeking to run in the replacement election and a larger number of voter signatures needed to trigger a recall.

The poll, conducted in the first week of September, also found widespread frustration with the price tag of a standalone, statewide election. Sixty-one percent of likely voters said that they felt the recall was “a waste of taxpayer money,” the strongest reaction of statements offered in the survey.

Where are we with ballot counting?

As of Wednesday, about 74% of the votes cast in the recall election had been counted, and the margin was wide enough to assure Newsom will easily remain in office.

As The Times’ Laura J. Nelson reported, political analysts are still waiting for more complete totals to answer some questions:

At what levels did Latino voters and young people turn out? What happened in rural areas? And what do the results mean for California’s hotly contested U.S. House seats?

Out of the more than 9.1 million votes tabulated as of Wednesday, nearly 64% supported keeping Newsom in office. The Associated Press estimates that about 13 million people voted, meaning as many as 4 million ballots are still uncounted — making a granular analysis of voter behavior or demographics almost impossible.

More accurate estimates from each of California’s 58 counties will be reported to Secretary of State Shirley Weber on Thursday night, state officials said.

Higher vaccination rates correlated with higher support for Gov. Newsom in the recall election, and vice versa, analysis of voting data shows.

What do we know about the California recall process?

Voters were given the power to remove an elected official before the end of a term in office through an amendment to the California Constitution in 1911. In the years that followed, only one small change was made to the recall process. Although most recall efforts have failed to qualify for the ballot, similar concerns about the rules were raised in 2003, when then-Gov. Gray Davis, a Democrat, was ousted in favor of Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger.

The Times Thomas Curwen explained how it all began:

When California’s newly elected governor, Hiram Johnson, delivered his inaugural address on Jan. 3, 1911, he made a radical proposition.

My first duty, Johnson declared on that celebratory day, “is to eliminate every private interest from the government and to make the public service of the State responsive solely to the people.”

His words sent shock waves through halls of power accustomed to an easy exchange of money and influence. Determined to “arm the people to protect themselves” against such abuses, Johnson proposed amending the state Constitution with “the initiative, the referendum and the recall.”

The savvy electorate of the day understood that their governor, a Republican well-versed in the Progressive agenda, was arguing for voters to be given the right to place laws on the ballot through petition, to weigh in on laws passed by the Legislature and to remove public officials from office without cause or judicial procedure.

Ten months later, voters agreed, and representative democracy, the crowning achievement of the founding fathers in 1787, now had a powerful rival — direct democracy — that would leave an indelible mark on California’s political landscape.

“The people of the State of California are ready to rule,” Johnson said. “They have the intelligence and the sense to rule.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.