Has California’s unique brand of direct democracy gone too far? Recall is ultimate test

- Share via

When California’s newly elected governor, Hiram Johnson, delivered his inaugural address on Jan. 3, 1911, he made a radical proposition.

My first duty, Johnson declared on that celebratory day, “is to eliminate every private interest from the government and to make the public service of the State responsive solely to the people.”

For the record:

10:46 a.m. Sept. 5, 2021An earlier version of this article said Arnold Schwarzenegger became governor after winning 55% of the vote in the 2003 recall election. He was elected with 48.6% of the vote.

His words sent shock waves through halls of power accustomed to an easy exchange of money and influence. Determined to “arm the people to protect themselves” against such abuses, Johnson proposed amending the state Constitution with “the initiative, the referendum and the recall.”

The savvy electorate of the day understood that their governor, a Republican well-versed in the Progressive agenda, was arguing for voters to be given the right to place laws on the ballot through petition, to weigh in on laws passed by the Legislature and to remove public officials from office without cause or judicial procedure.

A nonpartisan poll finds that 62% of likely women voters approve of California Gov. Gavin Newsom while only 43% of men do.

Ten months later, voters agreed, and representative democracy, the crowning achievement of the founding fathers in 1787, now had a powerful rival — direct democracy — that would leave an indelible mark on California’s political landscape.

“The people of the State of California are ready to rule,” Johnson said. “They have the intelligence and the sense to rule.”

California, popularly heralded as fertile ground for personal reinvention, now had the ability to reinvent itself politically. Citizens, quick to slough off the trappings of the past, had tools for building their future, bringing a fluidity and dynamism to the legislative and electoral process that has only gotten stronger, if not exaggerated with time.

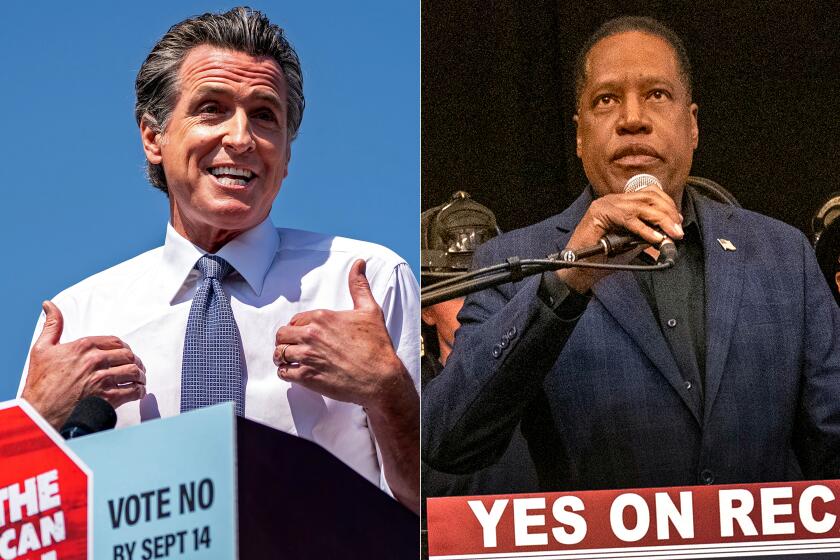

Today Johnson’s vision for California is in the final days of a campaign that kicked off in April when a little less than 5% of the population decided to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom, who took office in 2018 with almost 62% of the vote.

If the drama has at times resembled a sideshow with a traveling bear, a yogic healer and billboard celebrity among the 46 candidates, then it is a measure of how far the democratic spirit that Johnson championed has evolved.

Social media, celebrity candidates and attention seekers have altered the equation, but more than 100 years after Johnson’s reforms, there is no turning back.

“We have all been socialized in a state where we expect voters to directly flex their muscles,” said Thad Kousser, professor of political science at UC San Diego.

Although Johnson was not the first to come up with these ideas — Los Angeles physician and socialist John Randolph Haynes had a hand in it — Johnson gave them a larger stage and inaugurated a crusade and a movement triggering what has been called “California’s political regeneration.”

The timing was perfect. At the turn of the last century, Californians had had enough of the excesses and abuses of the Gilded Age, its well-heeled capitalists wrapping their tentacles around everyday life, fostering graft, quashing unions and abetting corruption.

Reform took the name of Progressivism, which as historian Kevin Starr wrote, “helped to transform the United States from an agriculture nation, owned by an omnipotent oligarchy and governed by the corrupt party machines … into an urban industrial society” dependent upon a prosperous middle class.

Unlike other Western states that similarly embraced direct democracy — Oregon adopted its version in 1902 — California endowed its amendments “with powers that make them far more muscular,” Kousser said.

To prompt a recall or the initiative process, nearly every state has a higher signature threshold than California’s, and California is the only state where an initiative can’t be undone without another vote by the people.

“We’re serious about direct democracy,” Kousser said, “and we use it more than almost any other state.”

Since 1913, 179 statewide recall attempts have been mounted, and more than 2,000 propositions have been written. Together they track the rise and fall of popular beliefs and fears, as well as economic and cultural aspirations. If California had a zeitgeist barometer, these efforts would be its measure.

Initiatives have raised and lowered taxes. One gave women the right to vote; another tried to ban gay and lesbian teachers from the state’s public schools. One allowed landlords and homeowners to discriminate on ethnic grounds. Another denied undocumented immigrants access to public healthcare.

Of the statewide recalls, only 11 have qualified for the ballot, and of those, only six succeeded. Jerry Brown, for his four terms as governor and as attorney general, holds the record for having been targeted 12 times, and Gov. George Deukmejian comes in second with 11.

Since 2019, six recall attempts have been filed against Newsom, the most recent succeeding upon the claim that he, among other insults, “implemented laws which are detrimental to the citizens of this state and our way of life.”

Once driven by more objective metrics than quality-of-life concerns, the recall process was intended to help voters root out malfeasance, even criminality from public offices that had no provision for impeachment.

When Marshall Black, a Republican state senator, was recalled in 1912 by Santa Clara voters, he had been convicted of stealing $124,000 from the building and loan association where he once worked.

When Frank Shaw, mayor of Los Angeles, was recalled in 1938, voters had had enough of the political machine he and his brother had assembled in a city that an attorney general called “one of the most corrupt, graft-ridden cities in the United States.”

Over the years, however, the threshold for voter indignation has fallen and partisan politics has filled a void left by the Progressive reforms, whose hallmark was not just a nonpartisan spirit, but according to historian Starr, a distrust among Democrats and Republicans of “big government, big corporations and big labor.”

“California Progressivism contained within itself both liberal and conservative impulses,” wrote Starr, who focuses on Earl Warren. In 1942, Warren entered both the Republican and Democratic primaries for governor, sweeping the former and losing the latter by only 11% of the vote. He handily won the general election carrying every county in the state but one.

Starr describes Warren as a Republican who “had liberal leanings regarding the social responsibilities of government,” a Democratic ideal that he took to Washington when he became chief justice of the United States.

But somewhere in the 1950s, fractures began to emerge in what Starr called “the Party of California,” and dissent became a more powerful political force than unity.

The Progressive movement laid the groundwork for how elections are conducted in California, but an overlay of race and politics and partisanship began to reshape the movement in the 1960s, said Raphael Sonenshein, executive director of the Pat Brown Institute for Public Affairs at Cal State Los Angeles.

As an example, Sonenshein points to Proposition 14, which was passed in 1964 by 65% of voters and overturned the California Fair Housing Act that had been enacted the year before to protect Blacks and people of color from housing discrimination. The proposition was eventually ruled unconstitutional.

“This was perhaps the beginning of what later became known as ‘the white backlash,’” Sonenshein said. “As politics became more diverse and partisan, direct democracy became enmeshed in that.”

The success of Proposition 13 in cutting property taxes helped propel former Gov. Ronald Reagan and his tax revolution into the White House. Subsequent propositions soon described a broadening chasm between liberals and conservatives, Democrat and Republican ideologies.

In the 1990s, the battleground was delineated with initiatives requiring English-language instruction in public schools (Proposition 227), prohibiting undocumented immigrants from accessing public services in the state (Proposition 187), and erasing affirmative action policies in the state (Proposition 209). Voters passed each, though Proposition 187 was ruled unconstitutional and Proposition 227 was repealed by Proposition 58 in 2016.

The initiative process had become a partisan tool, aimed at “fighting the emergence and incorporation of Latino political power that manifests itself in the election of Democrats or liberals, both Latino or white at state or local level,” said Fernando Guerra, professor of political science and Chicano/a studies at Loyola Marymount University.

The use of the recall as a means to shift the political equation has also increased. From 1913 to 1960, 11 elected state officials were targeted. Since 1961, there have been 168.

The tactic has also spread into lower elected offices that are nonaligned. Of the 50 recalls attempted this year, 22 have been directed at school districts, targeting either a member or the entire board.

“Something is accelerating,” Sonenshein said.

The rationale, though cloaked in ideology, is often personal and opportunistic. The key, Guerra said, is “to create a situation where there will be low turnout, where you can paint the incumbent as someone they’re not and the candidate as being neutral.”

In the mid-1990s, state Republicans mounted successful recall campaigns against former colleagues Paul Horcher and Doris Allen, who voted against the Republican caucus in favor of Democratic Speaker Willie Brown.

When Gov. Gray Davis was elected to his second term in 2002 with just 47% of ballots cast, Arnold Schwarzenegger saw weakness. Capitalizing on his celebrity, the actor-turned-politician became governor a year later with 48.6% of the vote.

The California recall election includes dozens of challengers as voters decide whether to retain Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Guerra, who describes himself as a liberal Democrat, calls the tactic “brilliant” and “a legitimate tool used by competing parties, ideologies or perspectives,” but he also considers it “a sign of weakness or desperation or one last gasp in overturning the trend of the power that one party has over another. It is the last stand of the resistance.”

Much as the electoral college reduces the disadvantage of small states in national elections, the reforms that Johnson championed in 1911 are populist vestiges of another time and place, leaving some to believe that they are ripe for an overhaul.

“Hiram Johnson is turning in his grave,” said Guerra, who imagines that if the former governor were alive today, he would be trying to wrestle a system away from “powerful monied interests.”

“What has happened is a distortion of the intent of the Progressives and what those founding fathers of the Progressive movement had intended,” Guerra said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.