Column: Why is it still so hard for former prisoners to become firefighters in California?

- Share via

For the second time in two months, Da’Ton Harris showed up for court this week in San Bernardino County, hoping that a judge would have mercy and expunge his criminal record.

He came carrying paperwork — proof that he had battled wildfires while in prison and proof that, in the years since his release, he has become a certified emergency medical responder and works for Cal Fire.

His petition to the judge rests on a new law designed to help formerly incarcerated people become firefighters and, in the process, help replenish California’s depleted firefighting ranks just as we head into another potentially disastrous wildfire season.

But in April, the judge delayed the proceedings to research the law, which he’d never heard of. This week, the judge sent Harris away because the state had yet to confirm his eligibility to take advantage of it.

“They pretty much tried to deny me from jump,” he told me, exasperated.

Indeed, in a state ravaged by drought, I find it mind-boggling that it’s still so difficult for people who gained experience battling wildfires while incarcerated to become fully certified firefighters. It seems like a win-win proposition that every judge should recognize: Men and women coming out of prison find meaningful jobs that put their skills to work, and California gains desperately needed trained firefighters.

Let’s hope this is just temporary. It is the first year in which thousands of Californians have been able to petition to have their felony records expunged under Assembly Bill 2147, written by Assemblywoman Eloise Reyes (D-Grand Terrace).

When Gov. Gavin Newsom signed the bill into law last year, many saw it as a solution to the long-running injustice of letting prisoners — most of them Black and Latino — do grunt work for slave wages in state fire camps, and then denying them firefighting jobs with proper pay and benefits upon their release.

Months later, it’s clear that AB 2147 is a solution. It’s just not a particularly quick or straightforward one.

Harris is just one example. For months, the Victorville resident has been working with Giovanni Pesce, an attorney with the Legal Aid Foundation of Los Angeles, in hopes of getting a judge to expunge his record, including the drug charge that led him to stints at multiple prison fire camps.

Without Pesce, Harris is convinced his case would’ve already been thrown out. And indeed Reyes urges all petitioners to use an attorney. The Judicial Council of California hasn’t even provided judges yet with the proper forms for AB 2147 expungements.

In the meantime, Harris is waiting on the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation to confirm to the judge that he successfully completed fire camp. He is used to waiting, though — and not giving up.

Get the latest from Erika D. Smith

Commentary on people, politics and the quest for a more equitable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

It took him years, long stretches of which were spent away from his wife and children, and a lot of workarounds to build a resume impressive enough to land a job with the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. And he did it, despite the fact that he lacks an emergency medical technician license, which he can’t qualify for unless his record is expunged.

“I was going to every fire station, telling them my story, showing them my qualifications,” Harris told me. “And they laughed at me. They laughed, and they told me I wasn’t gonna never be a fireman.”

Today, he’s also on staff with the Forestry and Fire Recruitment Program, a nonprofit based in Pasadena that provides training and support for former prisoners who want to become career firefighters. That’s how Harris found Pesce.

That’s also how Chris Tracy found Pesce after he was released from prison in August. He got out early, as part of the state’s safety precautions for COVID-19. While normally that would be welcome news, particularly for Tracy who has a young son back home in Escondido, the timing meant he missed joining an elite program designed for formerly incarcerated firefighters in Ventura County.

Instead, Tracy has resorted to looking for work with private companies that hire firefighters to protect their property during wildfires. The pay is decent, but he’d rather work as a public servant.

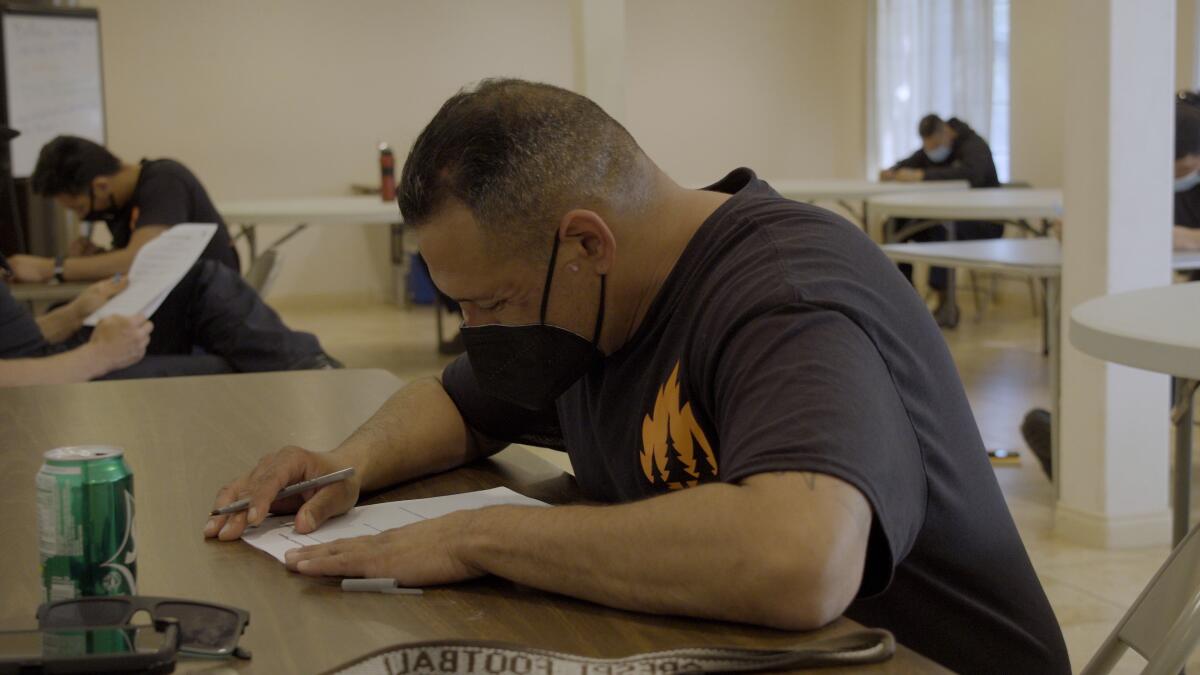

He’s preparing to go before a judge with a petition for expungement, but he’s worried that the way AB 2147 is written, it won’t allow the court to do away with his previous felonies for auto theft, leaving him unable to earn the EMT license necessary to be a fully certified firefighter with the state, and numerous counties and cities.

“It’s a good bill,” Tracy said. “It’s meant well, but I think it’s written poorly because it’s not expansive enough for [all of] us to be able to get an EMT cert, which a lot of these fire stations are asking for. It kind of defeats the purpose.”

Others have had more luck.

Rudy Amaya, who spent years in prison on a variety of drug charges, was released in 2011 but only recently was able to find work as a firefighter with the U.S. Forest Service. He thinks that helped him win over the judge last month and get his record expunged.

“The judge was even hyped about doing it because he said he had never seen anybody expunge their record to do what I done,” he told me. “He’s done it for people to go to other countries, but not for wildland firefighting. So he really commended me on what I’m doing.”

It’s unclear just how many people have tried to expunge their records so far under AB 2147, and even less clear how many petitions have been approved or denied or are still tied up in the process.

Reyes said her office is starting to collect that information as part of a broader assessment of what cleanup legislation she’ll need to introduce in the coming years. She sees AB 2147, which emerged as a compromise with the firefighters’ union, as an “initial phase.”

“Clearly, it’s not going to be perfect in its implementation because the judges and the attorneys and even the advocates are just learning about it,” she said. “I think it’s important that we give grace in that regard.”

But in the meantime, heading into wildfire season, there’s a shortage of firefighters and, after multiple emergency declarations from Newsom, the state is effectively in a drought. A group of state lawmakers has introduced a package of bills called the Blueprint for a Fire Safe California that’s designed to help, but it won’t come soon enough.

Reyes is the first to admit that becoming a firefighter should be much easier for people who spent months and, in some cases, years doing the back-breaking work of clearing brush and digging fire lines. Thousands of mostly Black and Latino men have served their time but are essentially still being punished for their crimes.

After years of pushing, the California Legislature passed a bill to help former prisoners become full-time firefighters. The governor should sign it.

Harris is proud that he has been able to find ways to work as a firefighter despite a system that has kept so many hardworking aspiring firefighters out. He already works with Cal Fire, but he wants more: to work for a fire department closer to home in Victorville so he can be near his family, be a better public servant with the proper certifications and “get that real money.”

He just needs a judge to cooperate. He’s due back in court in July.

“Everything in life takes time,” Harris texted me.

More to Read

Get the latest from Erika D. Smith

Commentary on people, politics and the quest for a more equitable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.