The fire that devastated a Sierra town created a pyrocumulus cloud. What does that mean?

- Share via

A deadly wind-driven fire that started Tuesday largely destroyed the small community of Walker, Calif., and has burned nearly 21,000 acres. It also gave rise to a dramatic pyrocumulus cloud.

“It was a remarkable wind event that caused multiple destructive wildfires,” said Alex Hoon, an incident meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Reno. “The winds were like a freight train. Winds of this magnitude are uncontainable.”

UCLA climate scientist Daniel Swain said seeing such plume-dominated fires anywhere in the American West is “pretty extraordinary by late November.”

California’s worst fire season on record has generated a number of pyrocumulus clouds. The Apple fire, which began in Riverside County near Banning on July 31, created an enormous plume of smoke that generated its own winds, The Times reported. The pyrocumulus cloud was visible from space and smoke spread over a large portion of Arizona in the following days.

This California fire season has also spawned some pyrocumulonimbus clouds, such as the one produced by the massive Creek fire, which started Sept. 4 and is still burning in Fresno and Madera counties.

NASA has called these “the fire-breathing dragon of clouds” because they’re the ultimate extreme pyrocumulus clouds, capable of injecting pollutant particles into the lower stratosphere, 10 miles above the surface of Earth.

What are pyrocumulus clouds?

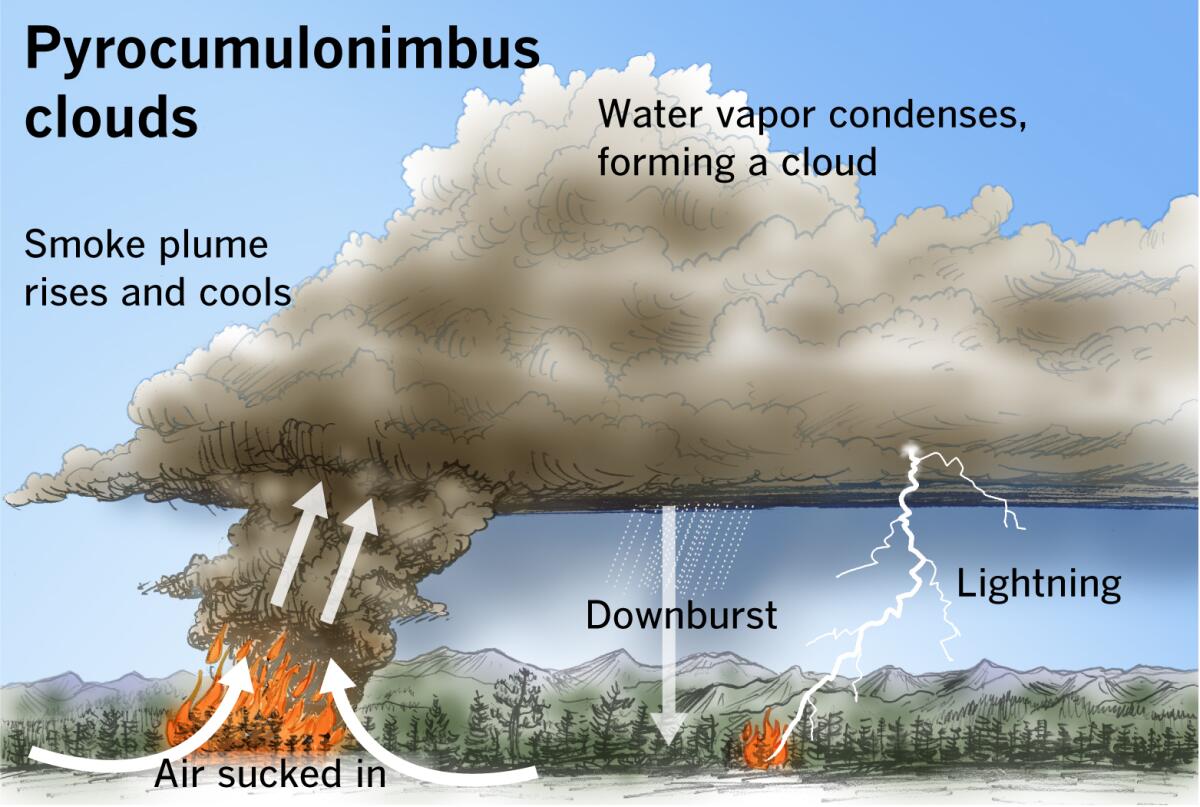

Intense high pressure can promote extremely hot, dry conditions that are ripe for the development of “plume-dominated” fires. This means that the fires produce smoke plumes that develop vertically like a thunderstorm. If the air over the fire is rising rapidly, as in a thunderstorm, the surrounding air will be drawn in toward the fire. This results in stronger, more erratic winds and extreme fire behavior. Fires such as this sustain and grow themselves.

How does this happen?

Fire creates heat and smoke. The heated air from the fire rises rapidly, creating what is called an updraft. Air from the surrounding area rushes in to the fill the empty space. Winds at the surface can be strong or erratic as a result.

Under certain conditions, that fast-rising air can create a fire tornado.

As the smoke and heated air from the fire rise, water that is already in the atmosphere and that has evaporated from vegetation that is being consumed by the fire will cool and condense. This forms a pyrocumulus cloud.

These are not the puffy white summertime cumulus clouds you may have drawn as a child. These “fire clouds” get their name from “pyro,” which means fire in Latin, and “cumulo,” which means heap or pile.

These are hot, dense, dark clouds full of soot and ash. They carry pollutants as high as 10 miles into the atmosphere, sometimes blanketing entire regions in soot and ash. “They’re the Darth Vader of cumulus clouds,” said climatologist Bill Patzert. “They’re not the side of Mother Nature that Ansel Adams photographed.”

When the weight of the moisture lifted into a pyrocumulus cloud overwhelms the strength of the updraft, the moisture can fall as precipitation. But the rain may evaporate on the way down because of drier air closer to the surface. Rain that doesn’t reach the ground is called virga.

This evaporation process cools the air, making it heavier and accelerating it as it plummets toward the ground. These powerful columns are called downbursts, potentially with winds in excess of 100 mph — as powerful and as damaging as a tornado. Downward flowing wind slams into the ground at speed and splatters in all directions like water from a faucet hitting the basin of a sink. Such erratic winds contribute to extreme fire behavior.

What is a pyrocumulonimbus cloud?

A pyrocumulonimbus cloud, or “fire storm cloud,” may form when a fire is big and intense enough.

Thunderstorm clouds are called cumulonimbus clouds — the nimbus part of the name comes from the Latin for “dark cloud,” because the moisture within nimbus clouds can block or reduce incoming sunlight.

Like a thunderstorm cloud, a pyrocumulonimbus cloud produces lightning and potentially stronger winds, which can start and spread more fires.

Some reports say a pyrocumulonimbus cloud formed near or over the Yarnell Hill fire southwest of Prescott, Ariz., on June 30, 2013. The fire had been ignited by lightning a couple of days earlier, but temperatures above 100 degrees with low humidity that afternoon created favorable conditions for rapid fire growth. There were thunderstorms in the vicinity that day, and Nick Nauslar from the National Interagency Fire Center in Boise, Idaho, says that outflow from a separate dry thunderstorm moved over the fire, resulting in a wind shift and stronger winds.

Nineteen firefighters from the Granite Mountain Hotshots were killed by the rapid growth and abrupt changes in the fire’s direction.

“Pyrocumulus clouds above active fires, especially large fires, are relatively common,” Nauslar said. “However, pyrocumulonimbus clouds are much taller and are associated with more extreme fire behavior and faster rates of spread. While not all pyrocumulonimbus clouds produce lightning, they do have the potential.”

Here are a few questions about pyrocumulus clouds, answered by Patrick Marsh of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Storm Prediction Center. The answers have been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Do pyrocumulus clouds collapse in the late afternoon, especially late in the season when there are fewer hours of sun and the ground begins to cool?

A: Not necessarily. In a nutshell, the fire will remain plume-dominated as long as the heat being released from the fire is warmer than the air surrounding it as it rises. This might lead someone to think that nighttime fires would be more likely to be plume-dominated because the surrounding air is cooler than in the afternoon. But cooler nighttime temperatures tend to result in increased relative humidity and less hot, less intense fires than in the afternoon. In addition, there’s something called the nocturnal inversion or nocturnal boundary layer. Because the Earth’s surface cools faster than the air above it, the air temperature within this layer increases with height. So the fire is weaker at night because of increased relative humidity, and the air being pulled into the fire is cooler. The smoke plume will rise above the fire at first, but at some point the plume runs out of oomph and spreads out horizontally.

Nauslar, the National Interagency Fire Center expert, adds that active fire behavior can continue above the inversion layer. For example, a fire on the middle or upper slopes of a mountain will probably remain active throughout the night because there is usually drier air and stronger winds above the inversion.

Q: Do pyrocumulus clouds occur at night?

A: Despite everything I said in my answer to [the first question], pyrocumulus clouds can and do occur at night. Several of the Colorado fires this year made significant nocturnal runs as a result of pyrocumulus or plume-dominated fires.

Q: So do pyrocumulus clouds occur mainly during the day?

A: They tend to peak late morning into the afternoon but can occur at all hours of the day.

Q: If or when a pyrocumulus cloud does collapse, is that essentially the same as when the weight of moisture overcomes the strength of the updraft that formed the cloud in the first place — in other words, a downdraft or downburst?

A: I’ve never heard of it referred to as ‘weight,’ but conceptually you are correct. The moisture-laden air aloft becomes too heavy for the updraft to hold it up and thus it falls back to Earth. This is known as the downdraft — or downburst if the falling back is intense.

What about the future?

Harsh conditions, including an expanding drought in the West and La Niña, provide an environment that summons such fire-breathing dragons. La Niña conditions, currently in effect in the Pacific, statistically result in a warmer, drier winter across the southern part of the United States, from coast to coast. In most of California and across the Southwest, drought — including extreme and exceptional drought — rules the landscape, as the U.S. Drought Monitor reports. So absent some serious rain, unfortunately, conditions may be ripe for more of these plume-dominated fires in the coming months.

“Given these conditions, fires are more frequent, they’re larger and they burn hotter,” Patzert said, “so we can expect these ominous pyrocumulus clouds to become a more common threat in a fire season that has expanded to include all twelve months.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.