Latino heroes: The few and far between

- Share via

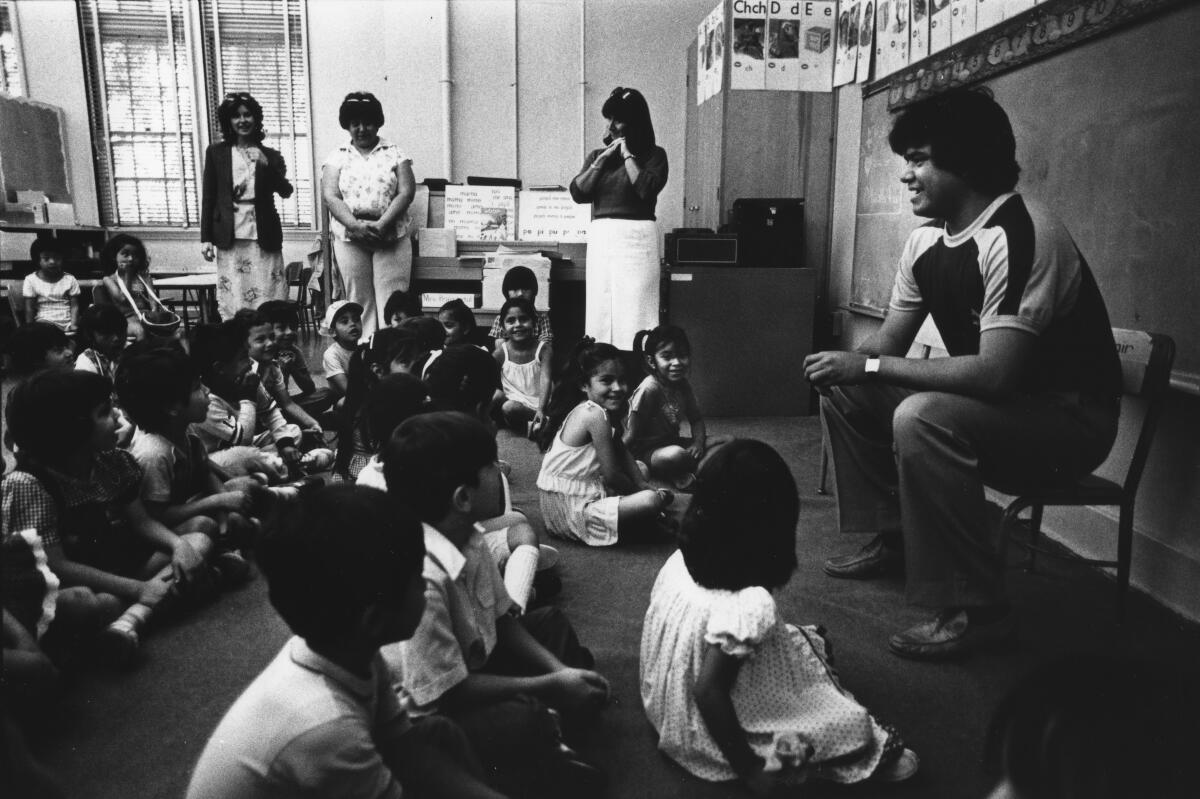

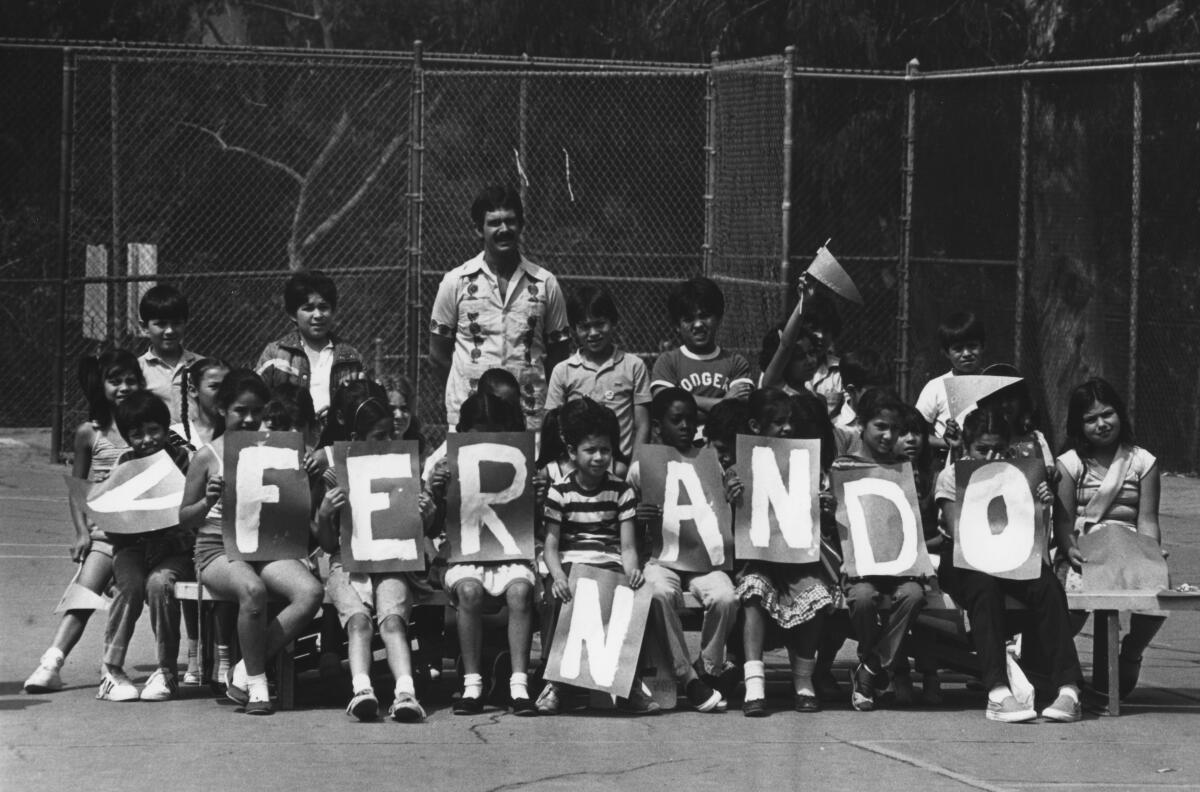

Nearly 5,000 baseball-hungry Latino youngsters swarmed over the small playground at the Eastside’s City Terrace Elementary School to get a glimpse of him. Some nuns admit to praying for him when he is scheduled to start a game.

Hundreds of Mexicans who otherwise care little about baseball make the long drive from the border cities of Tijuana and Mexicali to watch No. 34 on the Dodger Stadium mound.

Indeed, the rags-to-riches story of Fernando Valenzuela, who won 19 games in his rookie year with the Los Angeles Dodgers, has a special meaning for Latinos, no matter where they live.

But there is something amiss in all of this.

Many Mexican-Americans, including Francisco Perez, sense it. Said Perez as he leaned over his butcher counter in East Los Angeles, “Other than Fernando Valenzuela, I couldn’t tell you who are our heroes. We don’t have that many picked up by the media.”

“In our case, we’re hardly making a dent in the hero category,” said Juan Gomez-Quinones, UCLA Chicano studies director.

Ralph Esparza, a Los Angeles city housing administrator, was more blunt: “We don’t have any heroes.”

Extensive interviews and a Los Angeles Times poll support the suspicion that fewer Latinos have heroes—especially from their own ethnic group—than do Anglos or blacks. Latino psychologists believe that is a central reason why Valenzuela has such an enthusiastic following among Latinos, hungry for any kind of positive role model.

::

Latinos admired most by other Latinos

Los Angeles Times Poll of 568 Latinos statewide, conducted Feb. 27-March 3, 1983.

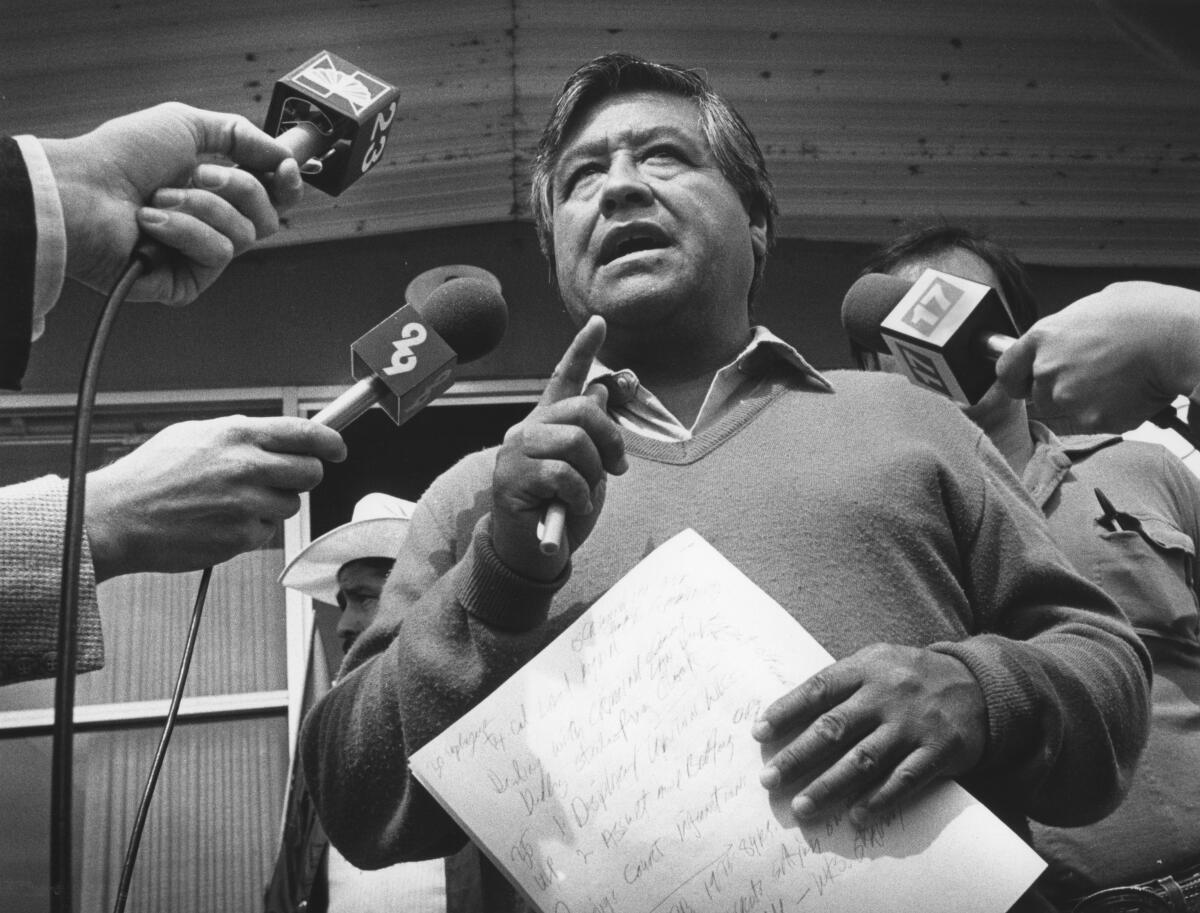

- Cesar Chavez, 57, was born into a farmworker family in Yuma, Ariz. A community organizer in the 1950s in Northern California, he founded the United Farm Workers of America in the mid-1960s to win better wages and working conditions for migrant workers. UFW-led boycotts against lettuce and table grapes made Chavez a force to be reckoned with. Named by 6% of those Latinos polled

- Ricardo Montalban may be the most visible Latino in the country as Mr. Rourke, star o, ABC-TV’s “Fantasy lsland.” The 62-year-old actor, born in Mexico City, was already a star in Latin America when he made his U.S. screen debut in MGM’s “Fiesta” in 1947. He founded Nosotros, a nonprofit group to promote job opportunities for Latinos in motion pictures and television. Named by 3% of those polled.

- ln 1981, Fernando Valenzuela accomplished something no other rookie in major league baseball had done-he was named National League Rookie of the Year and won the prestigious Cy Young Award in the same season. His pitching is crucial to the pennant hopes-and the gate receipts-of the Dodgers. Some believe Fernando, 22, attracts an extra 10,000 customers each time he starts. Named by 3% of those polled.

- Those Latinos mentioned by at least 1% of poll respondents include professional boxer Alexis Arguello, golf pro Lee Trevino, Mexican painter Rufino Tamayo, Argentine novelist and poet Jorge Luis Borges, Mexican singer Vicente Fernandez, singer Vikki Carr, singer Jose Feliciano, Spanish singer Julio lglesias, Mexican film stars Cantinflas (Mario Moreno) and Fernando Allende, Cuban leader Fidel Castro, former Mexican president Jose Lopez Portillo, current Mexican President Miguel de la Madrid, U.S. Rep. Henry B. Gonzalez (D-Texas), California state Sen. Art Torres (D-Los Angeles) and U.S. Rep. Edward Roybal (D-Los Angeles).

- Among those receiving scattered mentions were runner Alberto Salazar, KABC-TV reporter Henry Alfaro, KNXT weatherman Maclovio Perez, KMEX news director Peter Moraga, Mexico City news anchorman Jacobo Zabludovsky, soccer star Pele, Mexican tennis player Raul Ramirez, Los Angeles Raiders football coach Tom Flores, Raiders quarterback Jim Plunkett, formbr U.S. Ambassador to Mexico Julian Nava, labor activist Bert Corona, former California Secretary of Health and Welfare Mario Obledo, poet Amado Nervo, Mexican author Carlos Fuentes, Spanish novelist Miguel de Cervantes, Nicaraguan novelist and poet Ruben Dario, Colombian novelist and 1982 winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature Gabriel Garcia Marquez, author and scholar Ernesto Galarza, actress Rita Moreno, actors Cesar Romero and Anthony Ouinn, actresses Dolores del Rio and Carmen Zapala, singers Jose Luis Rodriguez and Miguel Aceves Mejiia, Miami Mayor Maurice Ferre, Nicaraguan guerrilla leader Eden Pastora (Commander Zero), Mexican revolutionary Gen. Venustiano Cailanza and California State Sen. Ruben S. Ayala (D-Chino).

::

That seems troubling in a land so imprinted with Mexican influence’ that President and Mrs. Reagan served enchiladas, tacos, refried beans, rice and baked fruit to Queen Elizabeth II at their Santa Barbara ranch to acquaint her with “Western culture.”

In the statewide Times Poll, one out of eight Latinos could think of no single person they admired most. Only one out of 100 blacks and Anglos answered similarly.

In the summer of 1983, The Times published a series on Southern California’s Latino community.

Equally interesting was the response from Latinos who could think of a person they admired most. They tended to name other Latinos less frequently than Anglos named other Anglos and blacks other blacks.

The Times Poll posed the question to Latinos in two different ways.

First, they were asked to name the person they admired most, without any mention being made of ethnic background. The top finishers: Pope John Paul II, followed by President Reagan, with Queen Elizabeth (in California at the time of the polling) and Valenzuela tied for third. More than 50 other names were also given, but few were Latinos.

Later in the questioning, Latinos were asked to narrow their choice and name the Latinos they admired most. This time, United Farm Workers of America founder Cesar Chavez headed the list, followed by actor Ricardo Montalban and Valenzuela.

::

Latino heroes of the past have ranged from Mexican revolutionary figures like Emiliano Zapata and Benito Juarez to the slain President John F. Kennedy, whose Roman Catholic religion and charisma appealed to thousands of Latinos who joined his Viva Kennedy clubs.

But no one in recent memory has generated such adulation among California’s 4.5 million Latinos as Valenzuela, the 22-year-old Mexican pitching star from Etchohuaquila, Sonora.

In some ways, Valenzuela seems an unlikely hero. Instead of being handsome and svelte, he is plain looking and beefy. He wears a uniform instead of a three-piece suit. In television interviews, he speaks in short sentences only. And except for a few “stay in school” and fire safety announcements, he seems uncommitted to pursuing social causes that could help poor Latinos.

During a recent interview at his new home in Merida, Yucatan, Valenzuela acknowledged his large Latino following, but said he is reluctant to lend his name to social causes.

“I do enough playing baseball,” Valenzuela said. “I can handle only one social issue at a time and right now it’s helping kids stay in school.”

Social causes aside, Valenzuela’s popularity is such that a word was coined to describe it—Fernandomania. And there is more to it than just throwing a fastball. He fills a void.

“He legitimizes our existence here in the United States,” said Manuel Gomez, a UC Irvine administrator and former California State University, Fullerton, history lecturer.

Each time the English-language press writes glowing words about Valenzuela, it reflects positively on Mexicans here in the United States, Gomez added.

Gomez also believes that Valenzuela’s success especially delights Latinos who find themselves competing in jobs daily with Anglos.

“He is a Mexican, who most middle-class whites think of as a lowly form bent over in a farm field,” Gomez said. “Yet, this Mexican, this lowly bastard, came to the United States and conquered the gringo in the quintessential American sport.”

“He is one of us,” said Perez, the East Los Angeles butcher. “I like him because he makes me feel proud. In this country, you have to be pretty good in any field to be recognized.”

Added Gomez, echoing the sentiments of other Latinos interviewed: “He became a hero in my eyes when he demanded more money last year. He wanted equal salary, parity, although some whites reacted angrily and said, ‘Send the wetback back (to Mexico)’ during negotiations.”

Latinos also admire Valenzuela because he continues to speak Spanish and shows no inclination to become a part of the Anglo world—a stance that many Latinos envy but for practical reasons cannot adopt.

Perhaps the Latino pride in Valenzuela is best illustrated by a mural done by the East Los Streetscapers, a group of Chicano artists.

The 8-by-10-foot mural portrays Valenzuela in his Dodger uniform in mid-pitch. His left foot is planted in Etchohuaquila, his birthplace, and his right foot is inside Dodger Stadium. His huge image, which takes up most of the mural, spans the U.S.-Mexican border. In the distant background is the ghostlike specter of Babe Ruth.

At Valenzuela’s left knee, a man with a coyote’s head (representing a smuggler of Mexican illegals) lifts the bottom section of the border fence as people dash across and then blend into a crowd entering Dodger Stadium, losing their Mexican features in the process.

::

Any discussion of Latinos in search of heroes invariably leads to the media.

UCLA psychology professor Armando Morales, for example, blames books, magazines, films, television and other media for omitting the positive role that Chicanos have played in society. When they are included, he said, it is often as bandits, youth gang members, domestics and other less-than-inspirational roles.

To a Latino already ambivalent about his cultural identity, such images intensify feelings of low self-esteem and self-confidence, Morales said. The young, he added, are especially affected.

Morales singles out the news media as usually preoccupied with barrio crime and youth gang homicides that unfairly stigmatize the Latino community.

Armando A. Moreno Jr., manager of the Glendale Federal Savings & Loan branch in Boyle Heights, said that a barrage of poor images in the news media makes it difficult “if not impossible” to persuade large corporations to invest in predominantly Latino East Los Angeles.

::

Some ‘Unsung’ Latinos

Latinos frequently complain that persons who have served their community well are overlooked by the media. “There are plenty of prominent Chicanos out there but the spotlight hasn’t been put on them,” said Thomas Castro, co-owner of a San Bernardino County Spanish-language radio station.

Here is a sampling of “unsung” Latinos in the local community:

- Leticia Quesada, urban relations specialist for a private corporation. Quesada initiated a stay-in-school lecture program for ninth-to-12th-grade Latinas in California, focusing on career planning. She hopes to expand it nationally.

- Actor Edward James Olmos. Few individuals can stir a Chicano high school audience like Olmos, whose powerful character as the dominant El Pachuco in the movie and stage versions of “Zoot Suit” epitomized the Chicano spirit. So far, he has managed to blend commercial success and ethnic projects 10 the extent that, as one admirer said, “ln him, we see ourselves. “

- Al Diaz, former reporter, editor and community newspaper publisher of the Eastside Journal and Belvedere Citizen. Considered Mr. East L.A.” by many, few individuals know more about the Eastside and its people than Diaz, who retired last year.

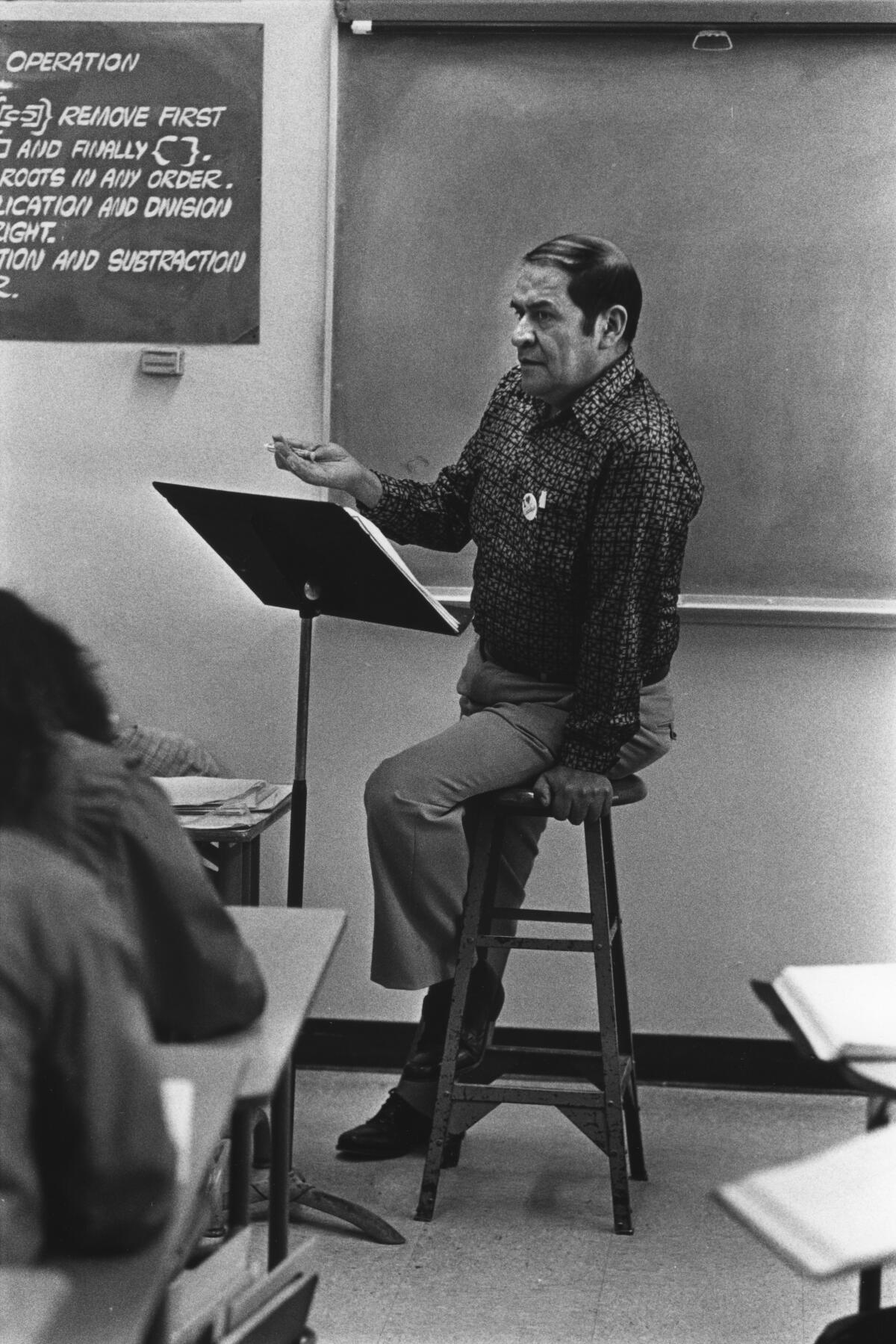

- Jaime Escalante, a Garfield High School math teacher. A demanding taskmaster, Escalante has been affectionately dubbed “Kimo” by his students, who think of themselves as ever-faithful Tontos to his Lone Ranger. Escalante has upgraded calculus courses and brought a new motivation to students at Garfield in predominantly Latino East Los Angeles. Last year, a testing service unsuccessfully challenged the results when 18 of his students who took an advanced placement calculus test passed — seven with perfect scores.

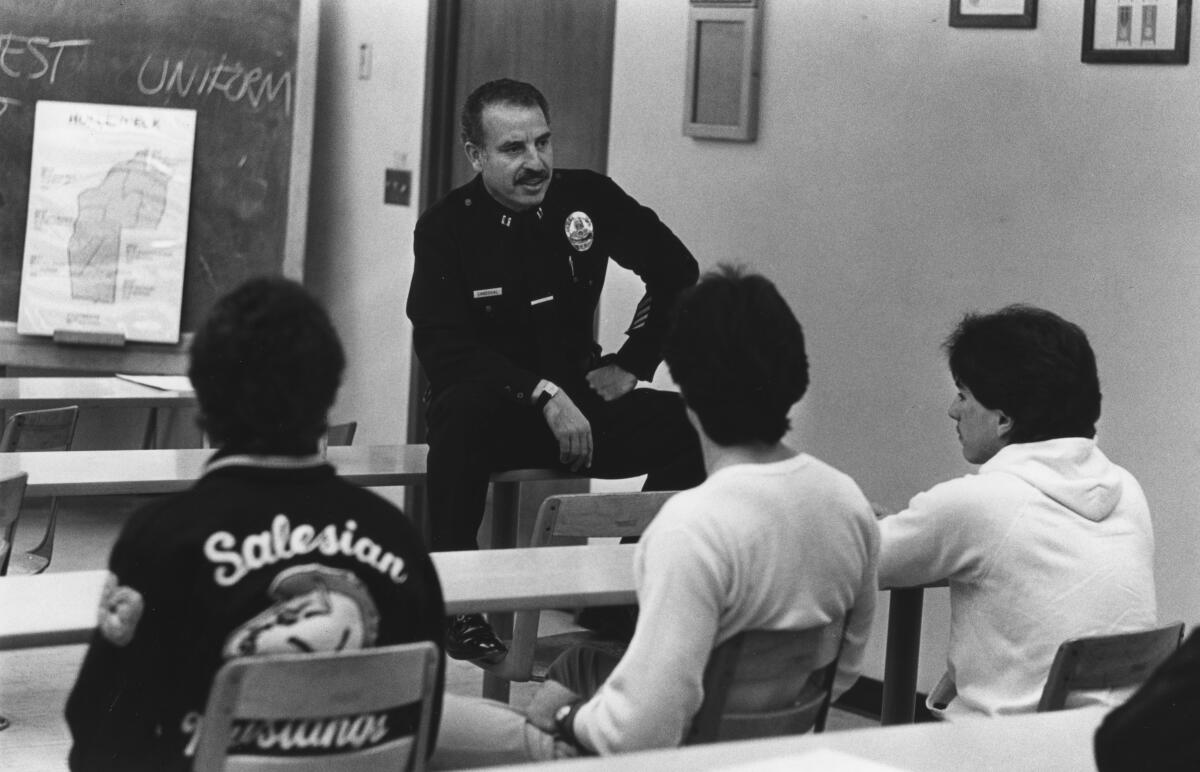

- Capt. Joe Sandoval, the commander in charge of the Los Angeles Police Department’s Hollenbeck Division in Boyle Heights. Sandoval is the department’s highest-ranking Latino officer. When Sandoval eats his favorite clam chowder at the police academy, his table is crowded with Latino officers, who look to Sandoval as their confessor, advisor and friend.

- Five Los Angeles Unified School District educators: Alphonso B. Perez, the district’s first Chicano high school principal; John F. Leon, an associate superintendent of schools; Ruben Holquin, a junior high school principal; William Zazueta, a retired school principal, and Marcos de Leon, who died in 1978. The five encouraged other Latino educators at a key meeting in 1970 to introduce bilingual-bicultural instruction in Eastside schools. They influenced the creation of the Assn. of Mexican-American School Administrators, and set the tone for a generation of Latino educators in Los Angeles.

::

“Look,” Moreno said, pointing to an office window, “Tell me. Do you see anybody getting stabbed out there? How about gang killings, you see any occurring? You don’t see any, but that’s the image that is portrayed in the news media.”

And even when Latinos become national heroes, they do not receive adequate recognition by the media, it is argued. Some contend that in the military, for instance, it is not widely known that Chicanos have won more Medals of Honor than any other American racial minority.

Morales said that when the media are silent on Latinos and other ethnic minorities, their intention may not be to condone prejudice, “but such, of course, is the indirect result.”

Television entertainment, Morales argues, reinforces the distorted perception among viewers that Anglos are “normal” and superior, and ethnic minority groups are inferior.

Morales cited as an example an episode of “Condo,” the ABC comedy series that aired for a time earlier this year.

In the episode, the daughter of a Latino barrio family moving into a fashionable condominium complex falls in love with the son of the Anglo couple next door—and then becomes pregnant.

“This type of role modeling says that Hispanic girls are promiscuous, end up getting pregnant and they sneak around their parents to get married without consent,” Morales said.

“It also says that one of the first moves for a Hispanic girl arriving in the middle class is to go after a white, middle-class male. This almost sets up an adolescent goal for the Hispanic.”

Actor Edward James Olmos, 36, who grew up near 1st and Indiana streets in Boyle Heights, is representative of a new breed of Latino performers attempting to counter negative television and screen images.

While he has accepted non-ethnic roles in the movies “Wolfen” and “Blade Runner,” Olmos’ appearance as the mystical El Pachuco in “Zoot Suit” cemented his popularity among Latinos. On the stage and screen, the role of Pachuco personified allegiance to barrio tradition and gave Chicanos a character they could identify with.

“El Pachuco was the most powerful and dominant character ever in American films for a Chicano,” Olmos said. “So many people identified with that ... it’s unbelievable.”

“l’m into being a full-blooded Chicano. I’m just like you,” he told a youthful audience recently. “But the advancement of the whole human race will advance Chicanos most, along with blacks, browns, reds and whites. You have to decide your own destiny.... You can’t blame your mother or your father, police brutality or prejudice. You have to respect yourself, respect other people and have discipline.”

Olmos is currently distributing his newest film, “The Ballad of Gregorio Cortez,” an independent production that humanizes the story of Cortez, a Mexican accused of killing a Texas sheriff.

“I’ve shown ‘Ballad’ throughout the Southwest and always the response by Chicanos is intense. In Denver, I saw 9-year-old kids crying and cheering when it was over. They just don’t have any kind of Hispanic hero being portrayed on the big screen.”

::

Barrio children, of course, need more than just sports stars and movie stars.

Lawyers, engineers, doctors and other Latinos with successful careers can be important role models. But there are not yet enough of those to go around.

To help fill the void, many suggest that books on prominent Latinos be put into use in public schools.

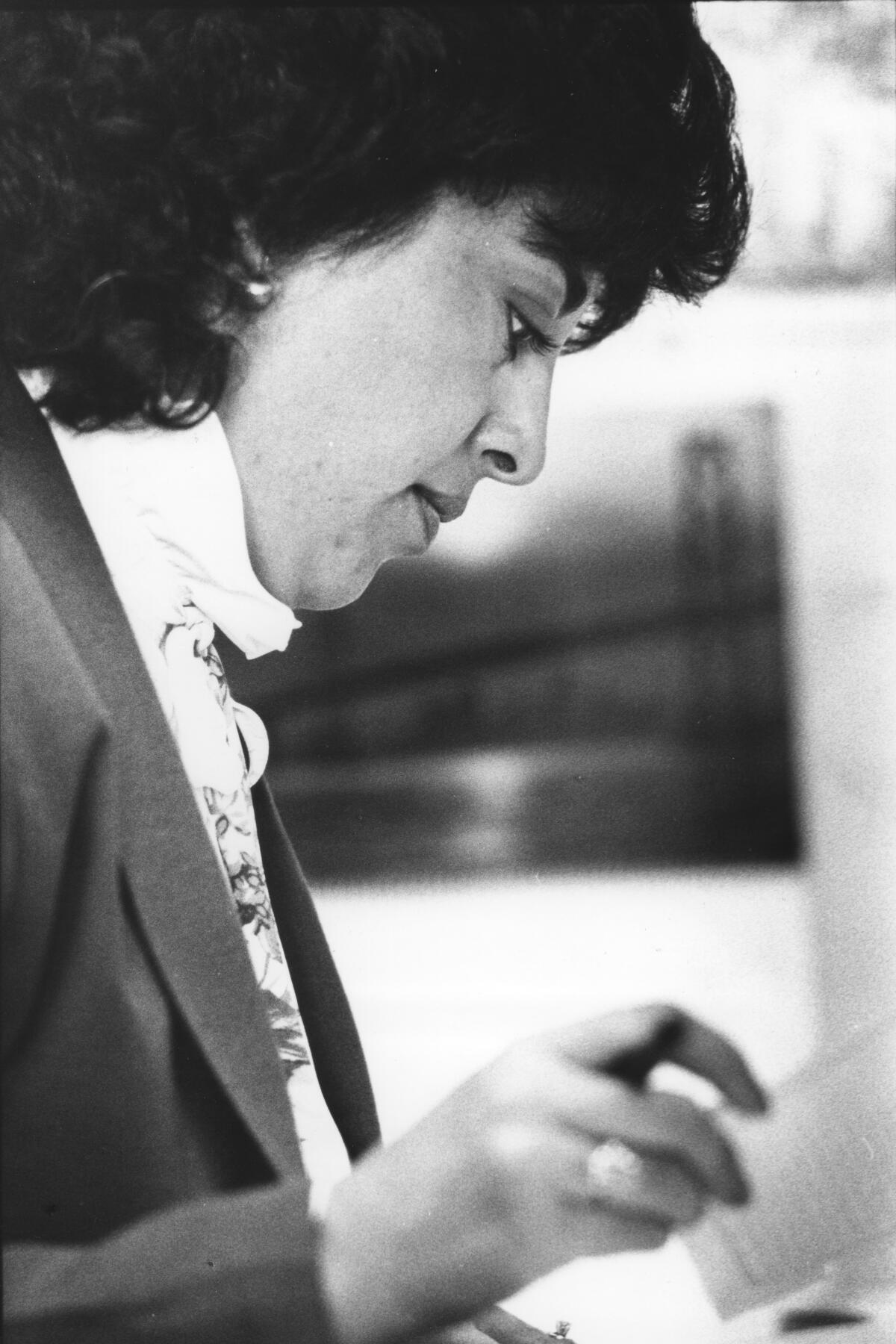

“When these children have no role models in the reading material within the first five years of their school careers, it’s a negative impact (because) all the heroes mentioned are not of their culture or language,” said state Board of Education member Lorenza Cavillo-Craig.

Most history books, for example, have neglected the accomplishments of Latino war heroes, according to the late Raul F. Morin, who wrote “Among the Valiant,” a tribute to the Mexican-American soldiers who fought in World War II and Korea.

“l could not help noticing the glaring omissions of the Spanish-named soldiers of the U.S. Army,” Morin said at the time of publication. “They were either left out altogether or given an insignificant role.”

Some think the hero dilemma for young and old alike is symbolized by the hyphen in the term Mexican-American. Latinos are in the middle of a cultural tug-of-war, the same conflict that affects most U.S. immigrants. It is difficult for a Latino to select heroes, some argue, when he is still trying to determine which culture he will embrace.

A small illustration of this was provided when The Times conducted an informal survey of Latino high school students in East Los Angeles.

Those who spoke Spanish said their idols included popular Spanish singing idol Julio Iglesias and Menudo, the teen-aged Puerto Rican rock group.

In predominantly English-speaking classrooms, the choices were more well-known Latinos like actor Montalban and labor leader Chavez.

One English-speaking Latino youth, though, expressed dissatisfaction with the survey:

“I’m sure there are many Latino heroes, but my heroes don’t happen to be Latino. My heroes are the Beatles.”

This story appeared in print before the digital era and was later added to our digital archive.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.