- Share via

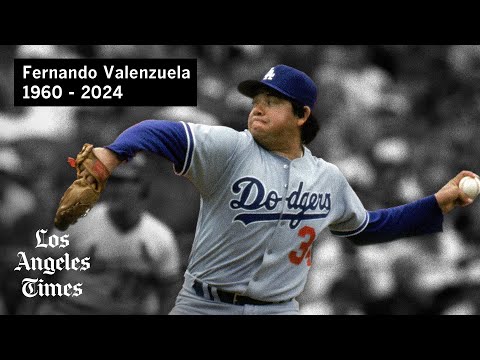

Hall of Fame Dodgers Spanish-language broadcaster Jaime Jarrín rose to national prominence when he became Fernando Valenzuela’s interpreter during his rookie season. Jarrín shared some of his thoughts about working with Valenzuela, who died on Tuesday at age 63.

Whenever a minor league player was called up, a Latino player, I always went down to the clubhouse to welcome the player in our language, to make him feel comfortable with the team, explaining to him what the Dodgers organization is, what are the guidelines to follow and all that.

And I remember distinctly that we were in Houston with the Dodgers in 1980, when they called and told me, we have a kid here who was brought up from AA San Antonio. I went down and it was Fernando. So I met this young man, 19 years old, long hair, gordito, didn’t speak a word of English, Indigenous features — and he caught my attention.

He was very, very introverted. He didn’t talk much, very gentle. But I liked him tremendously because he was humble. He looked humble and he looked surprised over having made it to the big leagues.

Fernando Valenzuela, the Mexican-born pitcher who led the Dodgers to a World Series win and vastly expanded MLB’s Latino fan base, dies at age 63.

By 1981, Fernando was designated as the third starter for the team. Jerry Reuss was going to start the first game, Burt Hooton the second, and Fernando was supposed to pitch the third game in the first series of 1981, but then Jerry Reuss hurt his ankle. Then they went to Burt Hooton, but he also hurt his toenail. Then they called Fernando, and that’s when what we all know as the famous Fernandomania began.

Since Fernando didn’t speak English at all, they asked a Dominican second baseman, Pepe Frias, to help Fernando, translating for him. And he did that after one of the games. Then later, they asked Manny Mota, who was a first base coach, to help Fernando.

But then Fred Claire, who was the public relations director for the Dodgers, came up to me and said, “Jaime, it’s not fair that we are bothering the ballplayers and the coaches to help Fernando as his translator. Since you work with the team and you are with the team everywhere, we would like you to help Fernando as his interpreter.” And I said, “Of course, my pleasure.”

And that’s how I started to accompany Fernando everywhere, on all the excursions.

It was always us, Fernando and me. Sometimes Fernando’s agent Tony DeMarco also came, and we always left a day before the team in order to meet the requests of the press in all the cities. And that’s how I started to become close to Fernando.

I was surprised by Fernando in that even though he did not speak much, neither Spanish nor English — he did not know any English — he was always attentive and kind with the press. I only gave him one piece of advice: I told him you are not obligated to answer every single question they ask you. If for some reason you do not like a question, kindly say, “I am not interested in answering this question. Next question, please.”

Fernando was always interested in facing the press, to try to always answer all the questions. And thank God we did not have any unpleasant incidents as I see other people have had with the press. Thank God everything went off without any problems.

Many believed that Fernando did not realize the success he was having. That’s not true. Fernando always knew everything that was going on around him, he was so smart during the game and very smart after he left the game. He was a marvel, really, fielding and knowing where to throw the ball in the blink of an eye. He was also a magnificent hitter, in spite of being a pitcher. He batted very well and he hit with power, too. I don’t think he would have gotten used to the designated hitter in use these days because he loved to hit. So he was a complete ballplayer for six years from 1981 until 1986. Fernando was truly an incredible show, truly incredible.

Fernando never changed, Fernando was the same Fernando as always. He realized that he was starring not only in a sporting event, a sporting phenomenon, but a sociological phenomenon. He realized that he had a great responsibility to the Mexican community in particular — also to Mexican Americans and Latinos in general. And I think his behavior was commendable. It was extraordinary and was a wonderful example for children and young people learning to overcome obstacles.

I sincerely believe that Fernando should have been voted into the Hall of Fame for one simple reason. Yes, he did not achieve the necessary numbers for most players, such as having more than 200 wins, but in the creed of the Hall of Fame it asks what have you done for baseball. And I believe that there is no player who has done more for the good of baseball than Fernando Valenzuela.

Fernando created an incredible Latino fan base that helped tremendously, not only the Dodgers, but baseball in general. Let’s remember that in the ’80s, baseball was in the doldrums. We had no idols, there was the threat of a strike that broke out in 1981 and that’s when Fernando emerged and saved baseball. Fernando has done so much, there is no other player, no other figure in Major League Baseball that has created as many new baseball fans as Fernando.

Players like Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale, Maury Wills, Orel Hershiser, they’ve been tremendous. But here the American-born children already knew baseball from school because they started playing the sport at the age of 5 or 6 years old.

With Fernando, something different happened: People from Mexico, Central America, South America who were totally indifferent to baseball suddenly became baseball fans to the point that the Dodgers created an incredible fan base with extraordinary economic power. All thanks to Fernando’s magic.

A look back at the life and career of Dodgers legend Fernando Valenzuela, the man who brought “Fernandomania” to Los Angeles in the 1980s.

When I started with the Dodgers, the Latinos were 8% or 10% of the people who came to the stadium. Today, Latinos are 42% to 46% of people who come to the stadium to watch games, and we owe that to Fernando Valenzuela.

So for those reasons I think Fernando should be in the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown.

It gave me great pleasure, a deep satisfaction, to see the Dodgers honor him by retiring his No. 34 [in August 2023]. It was one of the few times that I saw great emotion in Fernando. When the ceremony took place and he was walking from the dugout to the stage and the microphone near the mound, I saw him finally showing great enthusiasm and emotion, a smile from ear to ear, and he was happy. Everyone was there — his family, his wife, his two sons, his two daughters, his seven grandchildren. And for that, I salute the Dodgers who had the good sense to put Fernando in their ring of honor.

Now we must take pride in savoring the legacy that Fernando leaves us, the legacy that Fernando leaves to future generations. He came here as an immigrant to fulfill his golden dream of being one of the best to play professionally. It should inspire young people to work hard and realize that in this country, there are opportunities to succeed.

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.