- Share via

Victorville, Calif. — She sat in a corner of the hospital room, breathing into a tube designed to prevent pneumonia or the collapse of her lungs.

It was the fourth week of April, and the last two months had been so long and so monotonous that Janice Brown started counting the cars rolling by her window — just for something to do. The janitor and the nurses had become old acquaintances.

So, it seemed, had the coronavirus.

In the short annals of the Desert Valley Hospital’s COVID-19 unit, Brown is a person of some distinction. It’s a notoriety that no one would want — but sometimes in life you don’t get to pick what makes you special. Or how.

Brown, 66, was the first patient at Desert Valley to test positive for the coronavirus. One of the first to be released. She thought she was in the clear, spending weeks — masked but confident — walking around her sister’s home and backyard in Rancho Cucamonga.

Her doctor, Imran Siddiqui, certainly thought he’d seen the last of Janice Brown. Just days after he discharged her on April 3, she told Siddiqui that she was feeling great.

Two weeks after that follow-up call, Siddiqui spotted her name on the patient list. She had tested positive a second time.

The story of Janice Brown, two-time coronavirus patient, parallels the story of the hospital that treated her. Both narratives are built around a hope that the worst is in the past. Or, at the least, not waiting on the horizon.

By the time Siddiqui, medical director of Desert Valley Medical Group, watched Brown leave for the second time, he dared to hope that the COVID-19 unit of the hospital could soon be dismantled.

::

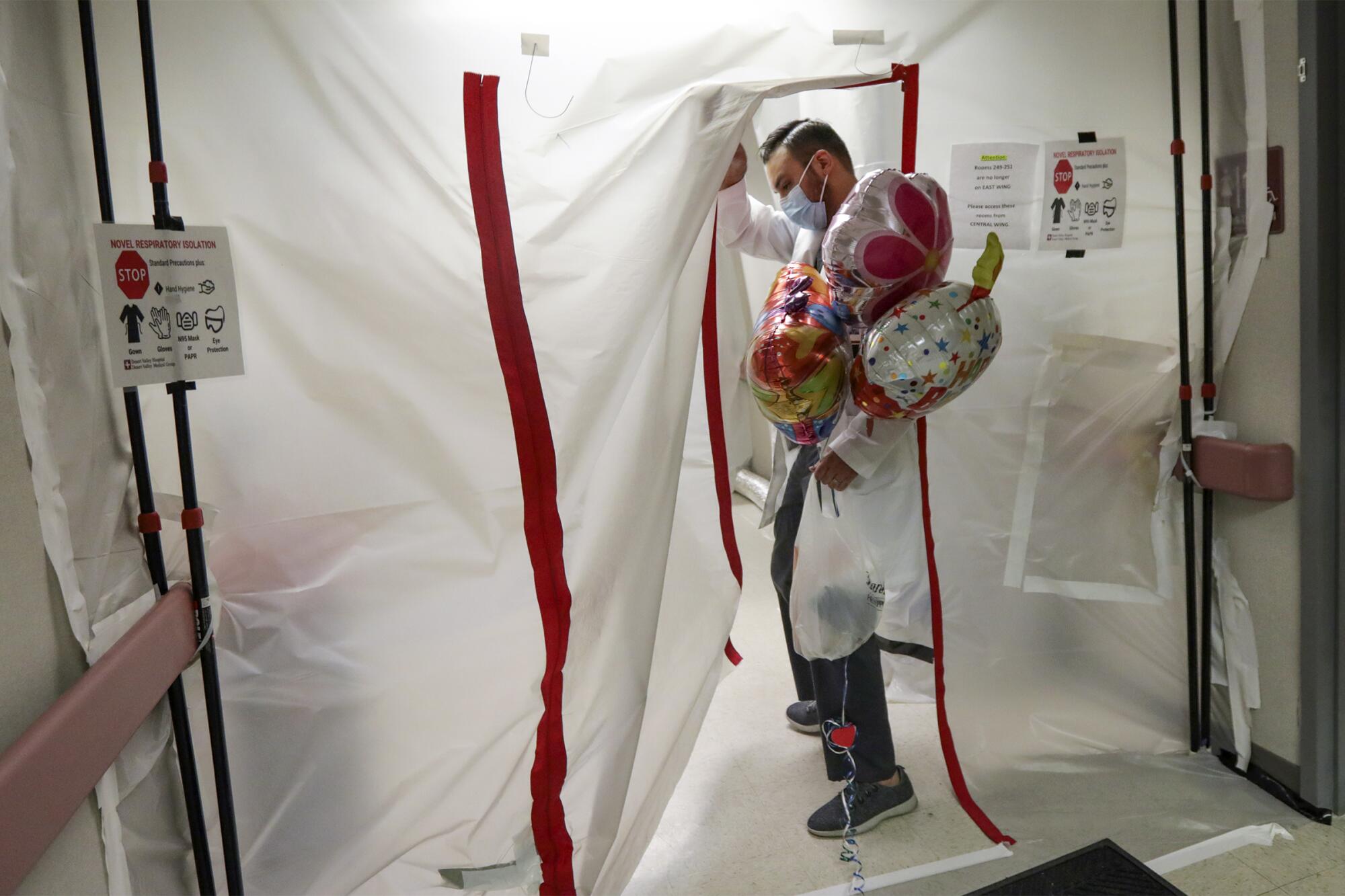

On Saturday, April 25, Siddiqui unzipped the plastic separating the rest of the hospital from the East wing, where a sign outside read “Novel Respiratory Isolation.” Trailed by a reporter and a photographer, he stepped inside the “donning” area to “gown up,” putting on the standard uniform: blue apron, shoe covers, a mushroom-cap hair cover, gloves and a surgical mask over his N95.

Reaching the COVID unit felt a little like the scene from “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial,” Steven Spielberg’s 1982 classic movie, in which Elliott walks through a huge plastic tube to reach his new best friend who’s been sequestered in a medical van.

Siddiqui passed a station where a handful of nurses monitored their patients’ vitals on computer screens. The RNs had volunteered to work in the unit, creating an informal staff so other nurses would not have to be exposed.

The doctor observed Maria Quintero as she did a “terminal” — or deep — clean on a patient room that had been vacated earlier in the day. Quintero, a member of the janitorial staff who works in the unit, used bleach to scrub the walls.

‘For you to put your lives on the line and then have to go back home to take care of your families — truly from the depths of my heart I say thank you.’

— COVID-19 patient Janice Brown

Finally, Siddiqui headed to the end of the hall, signing his name into the log outside room 238 before he stepped inside.

“Hello my dear, how are you today?” he asked.

“Not good,” Brown responded. She held a hand to her chest, where it felt as though it had been burning inside all day.

It had nothing to do with COVID, Siddiqui reassured her — it was just gastritis.

The day before she’d had a temperature of 101, he said, but her numbers were getting better. It was the fourth day of her second hospitalization.

Brown was anticipating her birthday three days later, on April 28, and yearned to celebrate somewhere other than the hospital.

“You’re in good spirits, right?” Siddiqui asked.

His patient hesitated before she responded, “Yeah, I’m in good spirits.”

Over the course of her life, Brown has dealt with cancer, two strokes, two heart attacks, renal failure and congestive heart failure. She has been on dialysis for over a year. With her age and host of underlying health issues, she is exactly the kind of person that COVID-19 chews up and spits out.

The coronavirus, Brown said, with a touch of irony, just felt like “the icing on the cake.”

::

It all started with a cold in early March. After two weeks, Brown thought she was on the mend. She’s been pastoring for 25 years, and gave a sermon at her Fontana church telling her flock, “No matter what comes, trust in God.”

“I didn’t know I was preaching to myself,” she said.

In a matter of days, Brown grew so sick she couldn’t stand. On March 24, she landed in the Desert Valley emergency room and tested positive for COVID-19.

The pain was so great, she thought she was going to die.

The hospital’s COVID unit was set up soon after she was admitted, in order to conserve protective equipment. Brown was its first resident and Siddiqui her doctor for the 10 days before her April 3 discharge.

The CDC recommends ending “transmission-based precautions” after a patient goes 72 hours with no symptoms, or has two negative tests 24 hours apart. The hospital follows a symptom-based strategy. After Brown went three days with no fever — without the use of fever-reducing medications — and doctors saw an improvement in her respiratory symptoms, she was discharged.

When Brown walked out, she thought she had escaped the clutches of the dreaded virus.

“I thought it was over,” Brown said. “Everybody thought it was over.”

Then, during dialysis on April 21, her blood pressure dropped precipitously and her temperature spiked. An ambulance took her back to the hospital, where she tested positive again.

In recent weeks, China and South Korea have reported that some patients who had recovered from COVID-19 tested positive again in follow-up visits. In extreme cases, patients in the Chinese city of Wuhan, where the outbreak began late last year, reportedly tested positive 70 days after recovery.

Doctors in both countries said they didn’t believe the patients had been reinfected, a worrisome possibility because of its implications for building widespread immunity to a disease for which there is no vaccine.

“[Brown] was the first patient that came back to the hospital that tested positive again,” Siddiqui said. “Is it a reinfection or the same infection? We don’t know.”

::

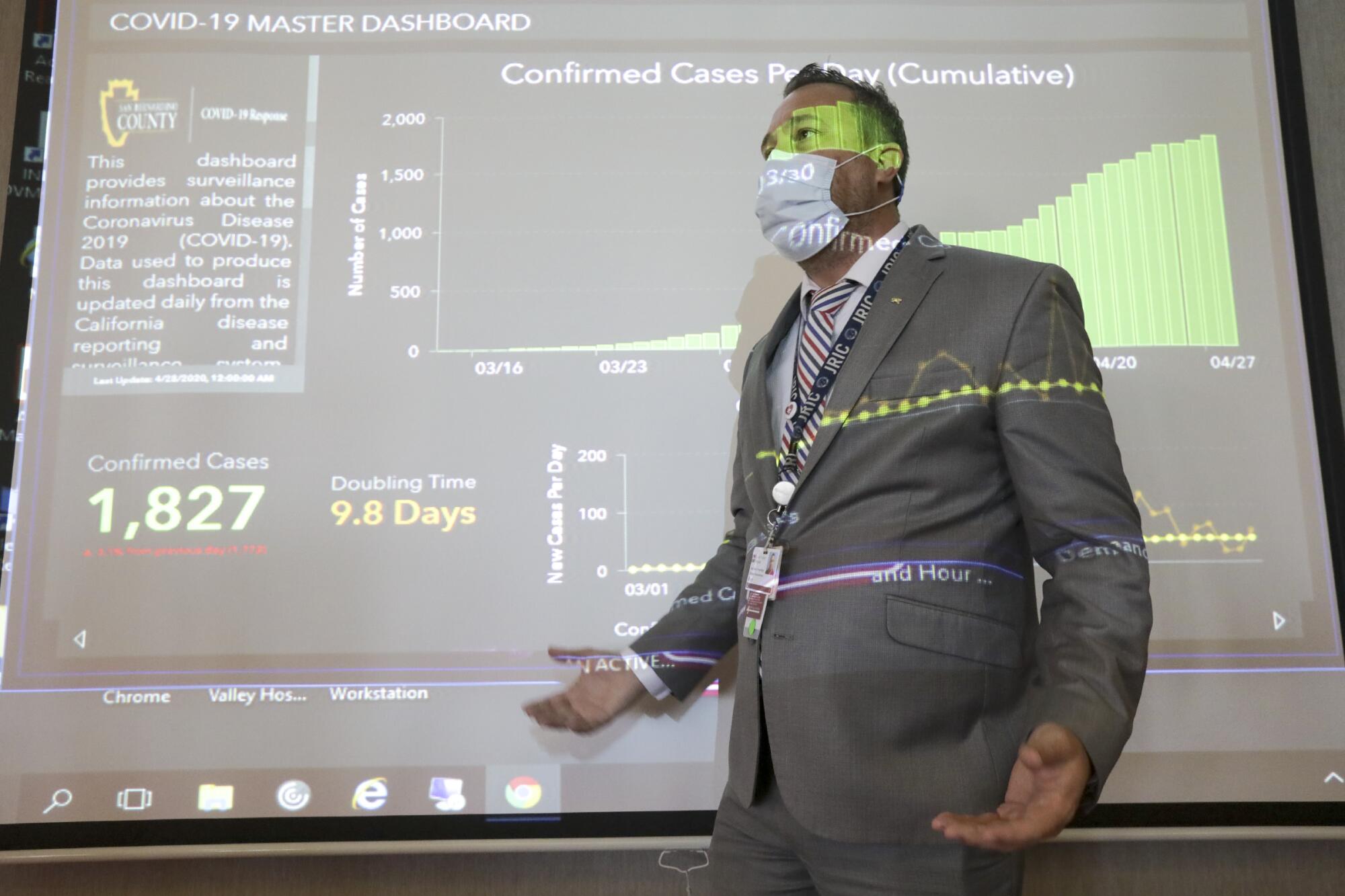

On April 29, eight days after Brown had been readmitted, about 30 people gathered in the conference room for a COVID-19 task force meeting. They talked about the state’s four-phase reopening plan and the need to stay vigilant.

Experts have warned against a broad reopening of the U.S. amid the pandemic, but dozens of states have reopened their economies in some capacity.

“We’re just trying to avoid hitting that second wave,” Brian Lugo, director of emergency preparedness and head of the COVID-19 response, told the doctors. “Let’s not get lax.”

During the meeting, members of the task force talked about plans to reopen labs and clear backlogs of tests that had been postponed due to the virus.

A white board showed that 289 people at the hospital had been tested for the virus and 25 had been discharged. Only two COVID-positive patients, including Brown, were in the East wing. Another two were on ventilators in the intensive care unit.

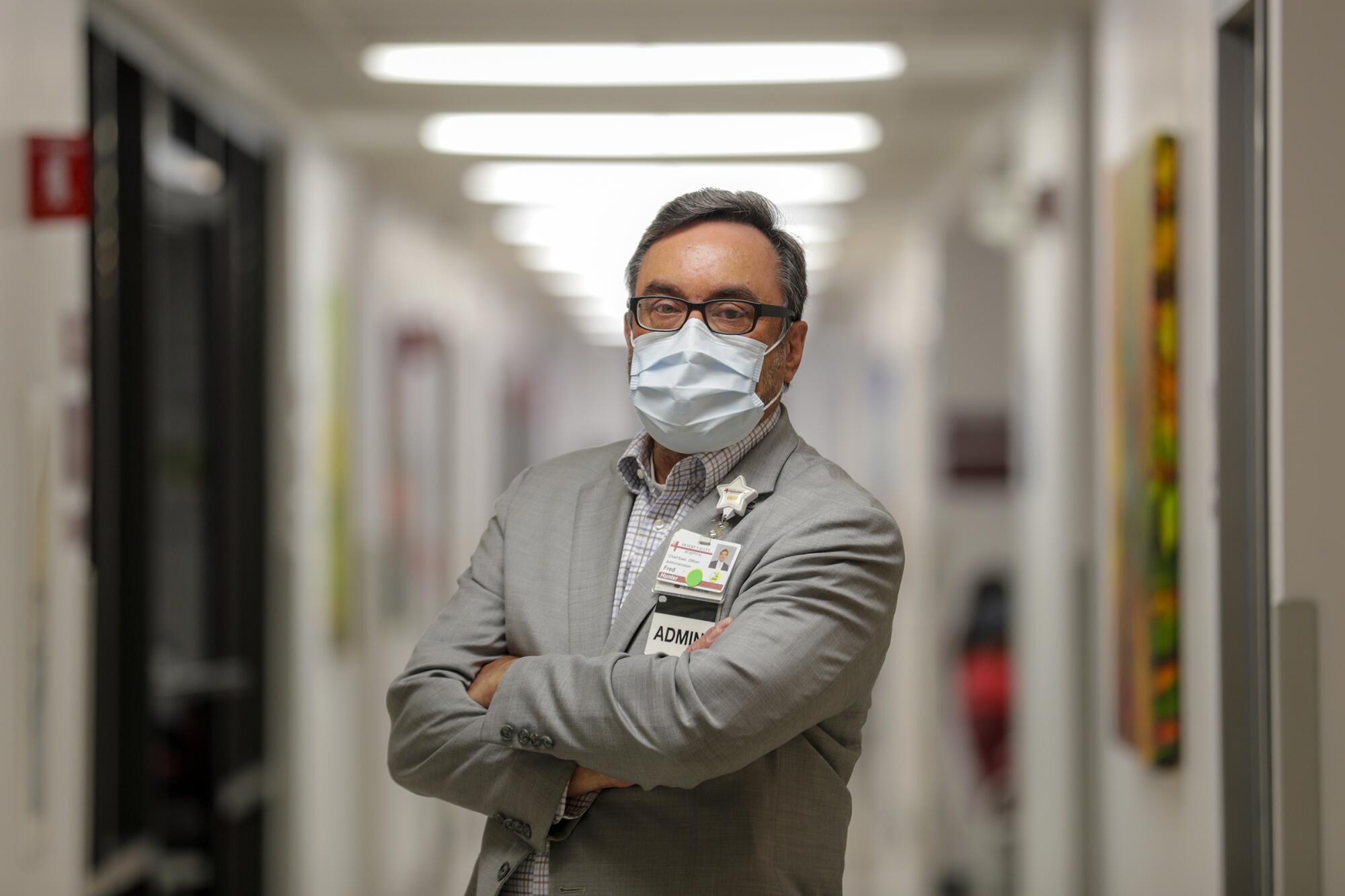

“I’m so glad we only have two patients in our COVID unit. That’s a good sign,” said Fred Hunter, chief executive officer of Desert Valley Hospital and Desert Valley Medical Group. “As we reopen this hospital for elective surgeries and elective procedures, let’s not make a mistake.”

He worried, he said, “that if we should open it up too soon, that these numbers could change in the wrong direction.”

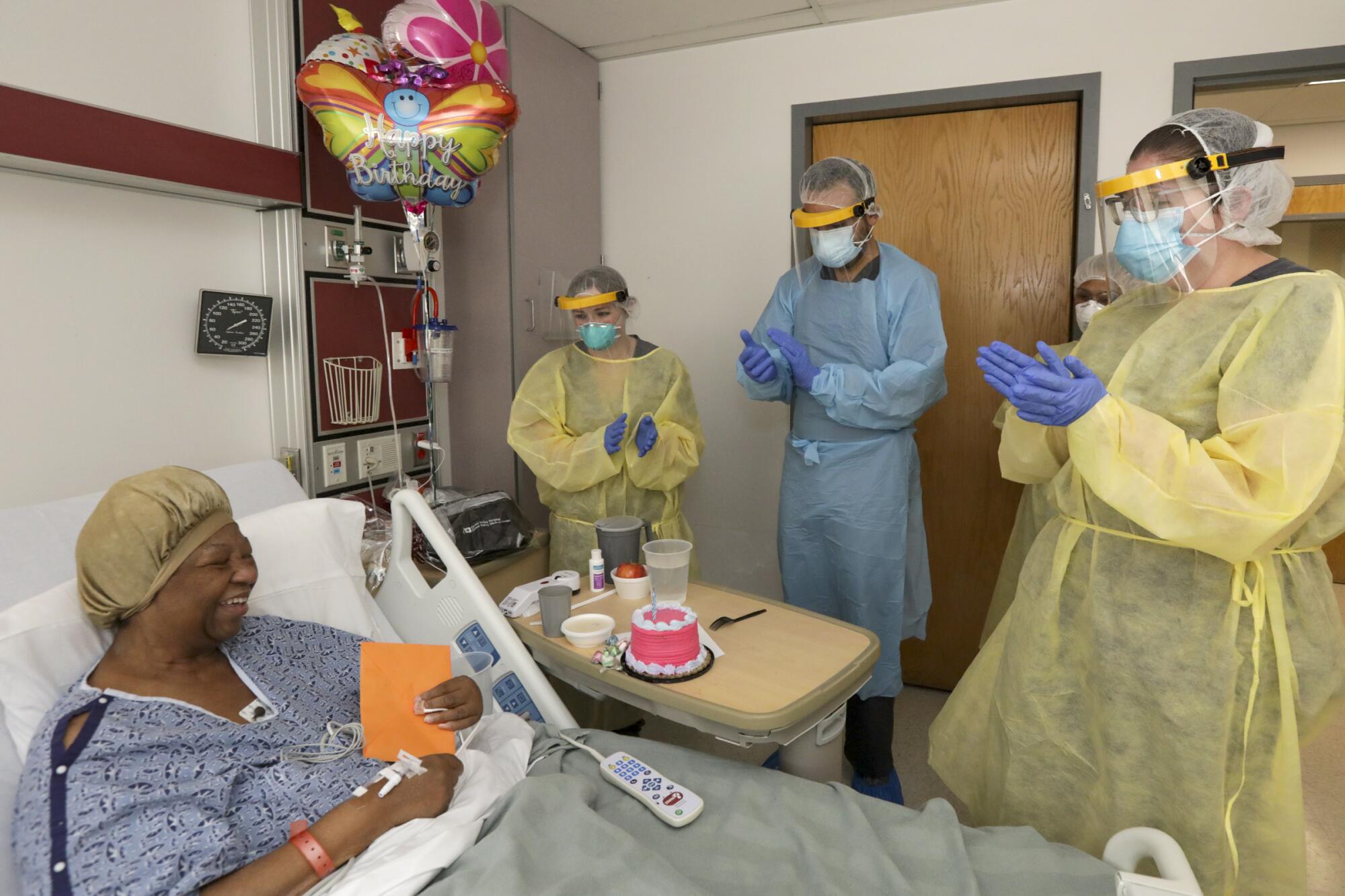

After the meeting, Siddiqui headed upstairs with three balloons and a small pink cake to mark the occasion of Brown’s birthday — a day earlier.

Inside the COVID unit, Becca Diaz wrote “Happy Birthday! You are an amazing patient,” on a card that had been signed by the unit’s workers. Diaz, a registered nurse, works in the unit three times a week and recalled how depressing it was when Brown tested positive a second time.

“It was almost like, is anything helping,” Diaz said.

Diaz joined a small crowd headed into Brown’s room — everyone in full protective equipment — holding a cake and singing happy birthday.

“I want to say thank you guys so much,” Brown said, growing teary eyed.

“It’s the least we could have done for you,” Siddiqui said.

“You guys have done more than enough. Put your lives on the line — for me,” she said.

There had, indeed, been sacrifices. Diaz used a designated “COVID bathroom” in her home to shower when she finished work; others spent weeks away from loved ones to protect them.

“I truly thank you, because you don’t know about the virus, I don’t know about it,” Brown said. “For you to put your lives on the line — truly from the depths of my heart I say thank you.”

That afternoon, Diaz wheeled Brown out of the hospital so she could reunite with her family — leaving just one person in the COVID unit. Hospital staff wondered whether it was almost time to dismantle it.

Then, a few days after Brown left the hospital for the second time, Desert Valley received a surge of patients who doctors thought might be infected with the coronavirus. One by one, they tested them — with only one positive result. As of Tuesday, one person remained in the unit.

But the hospital wouldn’t shut it down. At least not yet.

It was hard to envision what might happen in the future. Testing is increasing in California, which could lead to an influx of new patients. In addition, various counties in the state, including San Bernardino, are easing some restrictions. Face coverings in public, while “strongly recommended,” are no longer required.

“We’re basically living day by day,” Siddiqui said. “Who knows what’s going to happen tomorrow?”

Times staff photographer Irfan Khan contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.