- Share via

Priscilla Velazco brought her 16-month-old daughter to the hospital in Loma Linda on Christmas Eve, after the feverish girl had begun laboring to breathe.

Four days later, Emilia was still at Loma Linda University Children’s Hospital, and her mother was still at her bedside, trying to soothe the toddler as she fussed and coughed. Oxygen was being piped to her nostrils through a device called a nasal cannula.

“She was fighting them while they were putting it on,” Velazco said of the device. It has been hard, she said, for a child so young to comprehend what is happening, why this unfamiliar thing has to be on her face. “That’s the tough part — she doesn’t understand.”

Emilia Zarazua had fallen ill with respiratory syncytial virus, or RSV, just one of the viruses that had been filling the beds at the pediatric intensive care unit for weeks.

The collision of RSV, influenza, COVID-19 and other viruses has strained children’s hospitals across the country this fall and winter, including Loma Linda in the Inland Empire, where “these numbers are beyond what we’ve ever had,” said Dr. Cynthia Tinsley, chief of its division of pediatric critical care.

Two hundred children had been hospitalized with bronchiolitis, “which is what these viral infections are,” in its pediatric intensive care unit throughout 2021, Tinsley said. That was an unusually low number, one that the unit long since eclipsed in 2022.

“We are now doing more than that per month,” she said. As RSV and other viruses sent more babies and toddlers to the hospital, “we didn’t have enough cribs.”

More cribs had to be rented or bought and brought in. Nurses, respiratory therapists and other employees have been working extra days and overtime. Traveling nurses have been brought in to help. Hospital staff began to meet four times a day to plan out how to manage the growing numbers of patients, Tinsley said, going over staffing, supplies and medications.

Some children had been sickened by two or more viruses at once, worsening their illness. There are 25 beds in the Loma Linda pediatric intensive care unit, but some days its staff have been caring for 30 or 40 children and have had to expand into other units in the 364-bed hospital.

Tinsley said the death rate for children has thankfully remained extremely low, but the strain on pediatric hospitals echoes what those for adults were enduring a year earlier amid COVID. “Almost every day, you start the day out full,” Tinsley said. “And we end it late at night full.”

“Sometimes we get concerned about how long we’ll be able to sustain this,” Tinsley added, “if it doesn’t start letting up.”

At the Loma Linda hospital, medical staff can detect more than a dozen different viruses with a swab, said Dr. Laura Pruitt, an attending physician. One of the most common has been RSV, for which there is no currently approved vaccine. It has been especially taxing for the youngest children because their airways are so small and are more easily constricted.

Velazco, who lives in Moreno Valley, said that RSV was not on her mind when Emilia first started coughing. “But once her fever kept coming back — and pretty frequently — I knew it had to be something more than a cold,” Velazco said.

The Pasadena Rose Parade returns Monday sans pandemic restrictions for the first time in three years amid concerns of a “tripledemic” of COVID-19, RSV and the flu.

Emilia lay in the hospital bed, cuddling a rainbow stuffed animal and glancing up at a television playing cartoons. From time to time, she lifted one hand to wave or give a hesitant thumbs up to the gaggle of adults gathered in and around the room.

This was the first Christmas that Emilia was old enough to be aware of, Velazco said. During the holiday, a doctor had stopped by with some gifts, which were a welcome distraction from the strangeness of a hospital room. “It’s unfortunate that we have to be here,” Velazco said. “But I know they’re doing everything that they can to help.”

One building over, downstairs in the pediatric emergency department, Megan Duke was relieved that the usual deluge of young patients seemed to have paused that day, possibly because children had been away from school.

“It’s been such a needed break for our team,” said Duke, director of the pediatric emergency department and pediatric trauma services. “You can kind of see life coming back into them.”

There had been enough space to put an illuminated tree and donated gifts for the kids in a room usually used for medical procedures — something that Duke said would have been impossible a week earlier.

But “it’s not gonna last,” she said, explaining that their numbers usually rebound after holiday gatherings.

In November, the pediatric emergency room at Loma Linda was averaging nearly 200 patients a day, and “now we’re back to about 140,” Duke said — still a high number for a department with 26 beds. To expand its capacity, it had set up chairs in the hallways, separated with privacy dividers, where clinicians could attend to patients who were not as seriously ill.

Inside one room in the emergency department, nurse Mollie Perez asked Merlina Segeda Rendon how she was feeling. The 12-year-old, who has leukemia, had tested positive for the coronavirus on a rapid test at home. At times, the preteen translated questions into Spanish for her mother, who said Merlina had been suffering a fever that would dip a little after she took Tylenol, only to resurge again.

“Short of breath? Or just a cough?” Perez asked the 12-year-old.

“Just a cough. And dizziness,” she replied. “And then I threw up this morning. And my back hurts.”

The nurse told her that her oxygen levels were good — news that the girl relayed to her mother in Spanish — and asked her to sit up and take a deep breath so Perez could listen to her lungs.

Perez reassured her mother that Merlina looked as though she was in good shape, but that the oncologist might want to draw some blood to be sure, and maybe give her some medicine. She told the girl and her mother to push the call button if they needed anything before she stepped out of the room again.

The coronavirus and the flu are surging in California. Here are the steps to protect yourself from getting sick during the holiday season.

This was the second time that Merlina had gotten COVID, her mother, M. del Carmen, said. She worried aloud about how the leukemia might complicate efforts to treat her daughter for the virus.

In November, the San Bernardino County health officer urged families to take precautions such as washing hands, getting flu shots and COVID vaccinations and masking when indoors, warning that high rates of respiratory illness were “severely impacting capacity in our pediatric hospitals.”

That same month, the Children’s Hospital Assn. and the American Academy of Pediatrics wrote in a letter to President Biden that “these unprecedented levels of RSV happening with growing flu rates, ongoing high numbers of children in mental health crisis and serious workforce shortages are combining to stretch pediatric care capacity at the hospital and community level to the breaking point,” stating that more than three-quarters of pediatric hospital beds were full across the country.

At Loma Linda, Tinsley and other physicians said they had gotten calls seeking beds from Mexico, Northern California and outside the state. Some families are as far as a nine-hour drive away from the hospital, Pruitt said, straining parents who are juggling child care for their other kids.

As Tinsley was showing a reporter around, she stopped to greet nurse Chovi Parenteau and asked, “Did you have a good Christmas?”

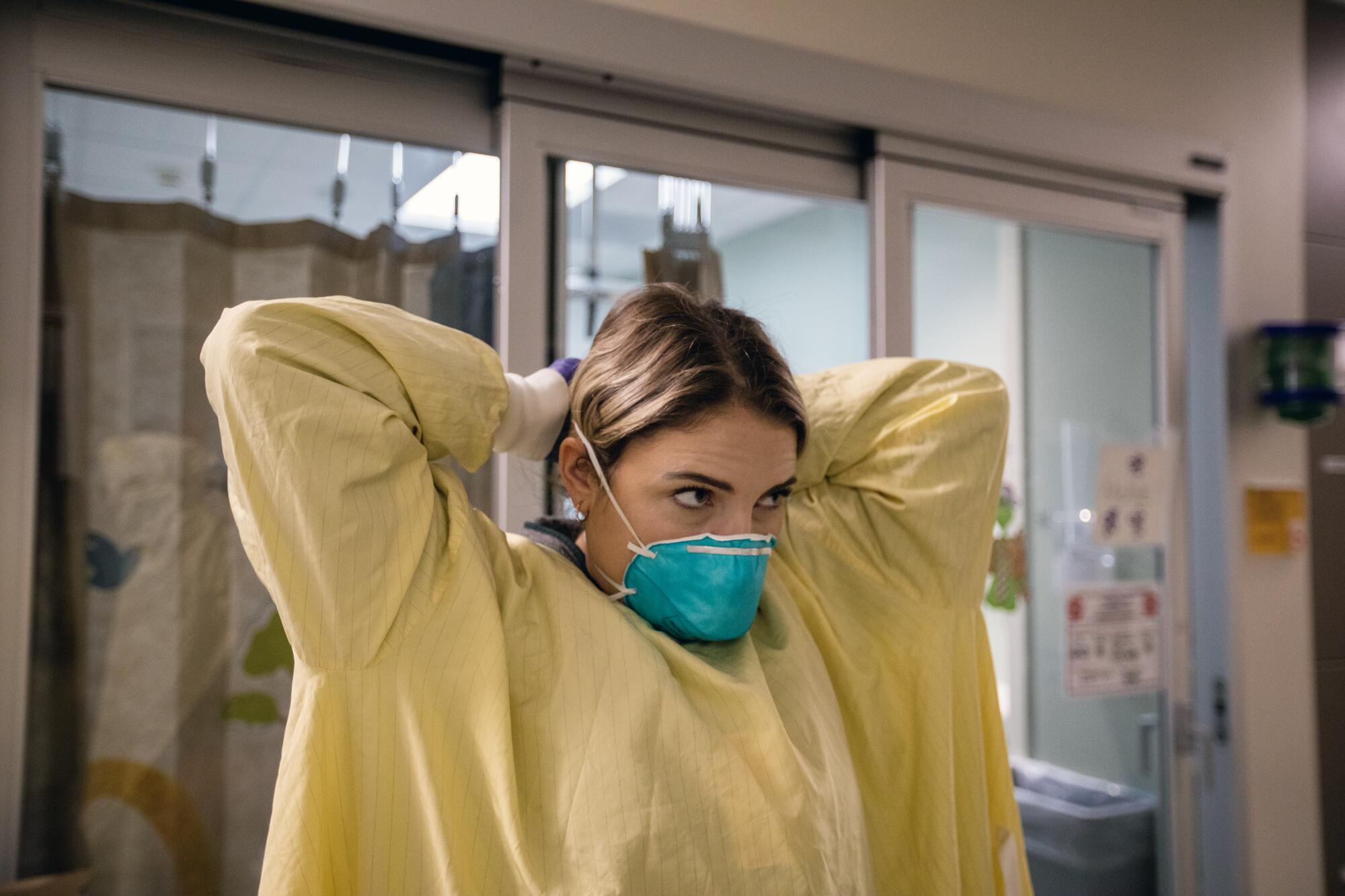

“I was here!” Parenteau answered, pausing outside a hospital room in a protective yellow gown and gloves.

“God bless you,” Tinsley replied. Before she continued rounding the unit, Tinsley reached over to give the nurse a sideways hug.

“It’s going to be better next year,” Tinsley told Parenteau. “It’s got to.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.