Pete Wilson still defending Prop. 187 and fighting for a better place in history

- Share via

The burly Latino guard stationed near the entrance of the Fox Plaza skyscraper in Century City looked as if he could have been one of my cousins back in Anaheim. But that didn’t stop him from grilling us in accented English about what we were doing as we tested our microphones and recorders in the lobby.

“I’m here to interview Pete Wilson,” I replied.

The guard’s face instantly took on a sour look. He pointed us to the concierge, who evidently had been expecting us.

Two more layers of security later, each with people less willing to engage in small talk than the previous, my producer, Abbie Fentress Swanson, and I were on an elevator speeding toward the 28th floor.

The door opened to the offices of Browne George Ross, a bicoastal law firm where Wilson serves as counsel. The receptionist asked us to wait on white leather couches. Before us, big windows that offered a fabulous view of Los Angeles illuminated the multiple rooms. On the walls were framed, black-and-white photos of ballerinas en pointe and cityscapes that seemed ordered from the catalog of Restoration Hardware.

Soon, we were ushered into a conference room. And in less than a minute, Wilson entered with a smile and a “How are you?”

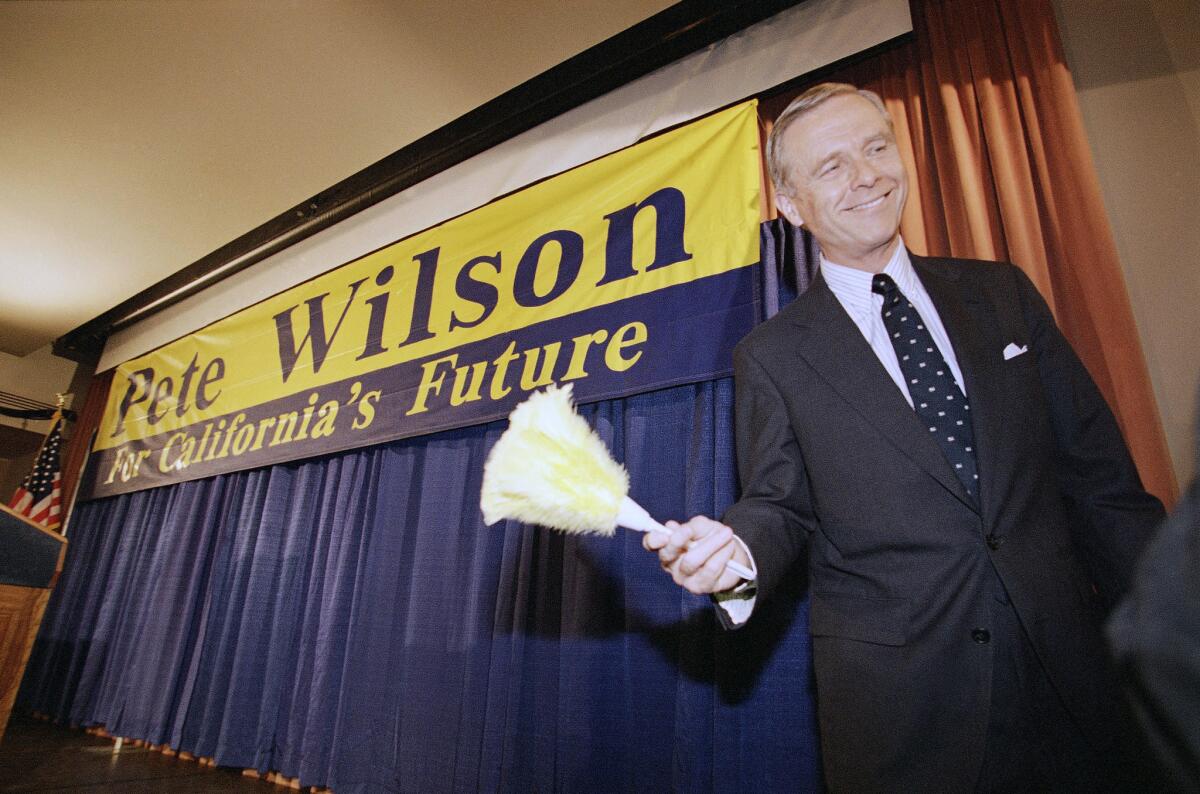

He’s now 86, sharp of mind and fashion, with a firm handshake and strong, if gravelly, voice. His signature helmet of hair remains full and parts to the right, the same style he wore as San Diego’s boy-wonder mayor in the 1970s.

I was surprised at how slight he was, considering the huge shadow he has cast over California for decades.

Among my peers, Wilson’s about as much a legend as La Llorona, El Cucuy and all the other monsters our parents scared us with as children — except he was the real thing.

“Why don’t we sit [at] this end of the table?” he told me as Abbie set up our mics, gesturing to an area away from the harsh sunlight.

“Out of the heat,” I quipped.

For two months, I had sought Wilson to interview for a one-hour podcast I released in early November about the 25th anniversary of Proposition 187, and how the ballot measure targeting illegal immigration forever changed California After the podcast release, he agreed to talk with me and there was excitement among my friends and people who have followed my work on immigration over the years.

They wondered if I would belt out a collective scream on behalf of la raza or grill him, a la “Frost/Nixon.”

I was concerned the interview would just be going through the motions. Old California vs. New, and so on and so forth.

I knew he’d stand by his record, even if I thought his support of Proposition 187 depicted people like myself and my friends and family — immigrants in the U.S. illegally and their American-born children — as acid thrown on the California Dream.

I didn’t expect him to express remorse, or have any. I didn’t imagine Pete Wilson suddenly losing his cool and dressing me down like Joe Pesci’s character did to Ray Liotta’s in “Goodfellas.”

In other words, I didn’t expect much theater. After so many decades in politics, I didn’t really expect Wilson to crack.

But I still felt that I had to crack that veneer and get at something deep.

During our hour and a half together in his office — more than double the original time I had requested — we went back and forth about his legacy. He was annoyed.

“Hell no, it’s not fair,” Wilson said when I asked him how he felt about being forever tied to the 1994 ballot initiative that sought to deny public services to immigrants in the U.S. illegally.

He was defiant: “Every time I have ever challenged [critics] to find one word that could be construed as racism in the campaign for 187, they have been unable to do so.”

Host Gustavo Arellano looks at how Prop. 187 helped turn California into the progressive beacon it is today.

He was unapologetic: “What you’re going to find out is if you don’t do a better job of controlling the border, it is gonna be all over the country.” That’s what Wilson said he told the federal government during his governorship if it didn’t take seriously the “problem” of illegal immigration.

And, at times, he lamented his page in history.

“It’s not fair,” Wilson repeated, when told that many Latino politicians in Sacramento openly mock him, long after he left office and politics. “And unfortunately, it’s easy, because who the hell talks back?”

Wilson also insisted U.S. District Judge Mariana Pfaelzer had let a lawsuit against Proposition 187 “languish in her ... on her desk for three years” before finally declaring it unconstitutional in 1997 because she was “politically opposed” to the proposition.

And he sure did not like any insinuation that he might have been motivated by bigotry. Or that he had appealed to bigots 25 years ago to score political points.

“I do resent the fact that a lot of people have knowingly portrayed me and others as racists,” Wilson said. “Because it’s not true. And it’s an evil thing to tell people who will believe you.”

Wilson’s business partner and longtime advisor, Sean Walsh, originally had told me the governor wasn’t doing much press.

And he had advised Wilson not to talk to me. He brought up examples where I slammed his boss, including an opinion column I wrote last year for the Los Angeles Times where I suggested Wilson celebrate his 85th birthday with a “dinner of crow tacos” for achieving short-term political victories that spectacularly backfired against him and the GOP in the long run.

I told Walsh all I wanted to do was ask Wilson questions. No tricks, no Borat-style high jinks.

We had started with a short phone call so Wilson and I could size up each other. For that, I focused on why Wilson thought so many Latinos despise him.

Wilson was the original Trump piñata — a figure upon which Latinos took out their political anger and fear.

In early November, California’s Latino Legislative Caucus took a crack at him with a video tied to the 25th anniversary of Proposition 187. Over somber piano music that segues into hopeful violins, nearly all of the caucus’ 29 members offer Wilson tongue-in-cheek gracias for what they say is his unwitting creation of today’s bluer-than-blue California.

Caucus members credit him for creating a “road map about how to fight back against racist, xenophobic policies and an opportunist leader,” a not-so-thinly-veiled comparison to President Trump. At the end, as they fill the screen “Brady Bunch”-style, all participants say, “Thank you, Pete Wilson!”

“They damn well should thank me,” Wilson said, arguing his 1991 decision to take away redistricting of congressional and legislative districts from the California Legislature allowed Latinos to grab the political power they have today — not his support for Proposition 187. “They’re [thanking me] for the wrong reason, but they should have gratitude.”

Wilson maintained that in the years since he’s left office, Latinos have thanked him. He shared a story about the opening day of the 1994 FIFA World Cup at the Rose Bowl.

The California governor knew what the sellout crowd had in store for him. A month earlier, Wilson’s campaign had released a controversial ad that featured night-camera footage of people running through the San Ysidro border checkpoint as a narrator growled, “They keep coming.” In a couple of days, the California secretary of state would announce that Proposition 187 had qualified for the November ballot.

Children walked alongside Wilson or dribbled soccer balls as he stepped onto the field at the Rose Bowl for the Colombia-Romania match. Their happy, cherubic faces didn’t soften the crowd.

“As I predicted,” Wilson cracked, “there was a chorus of boos.”

But Wilson said that a Latino deputy sheriff — “something like Gonzalez” — told him that his household of nine would vote for Wilson.

When the Los Angeles Times decided to endorse Pete Wilson in 1994, the newsroom rebelled.

A week after our phone call, I was sitting across from Wilson.

I started our interview by reminding Wilson of his early days. Then-Mayor Wilson met with Chicano activists in 1973 who were angry that San Diego’s police chief ordered the arrest of people suspected of being “illegal aliens.” He sent those same police to protect immigrants without legal status from gangs that assaulted them once they crossed into the U.S.

In 1977, Wilson asked the Carter administration to do “all they legally can” to prevent the Ku Klux Klan from setting up its own border patrol and hinted that the group was too friendly with local immigration authorities. And as U.S. senator, he opposed legislation that penalized employers for knowingly hiring immigrants without papers, arguing the move would discriminate against Latinos.

This part of his past is largely forgotten.

“It hasn’t been forgotten,” he shot back. “It’s been never known.”

That Wilson, I then argued, wasn’t the same Wilson who, in 1993, announced he wanted to ban children in the U.S. illegally from attending public schools, deny them and their parents state-funded healthcare, and asked the federal government to repeal the section of the 14th Amendment that granted citizenship to children born to immigrants without legal status.

What had prompted his change of heart?

“I didn’t change at all,” Wilson responded.

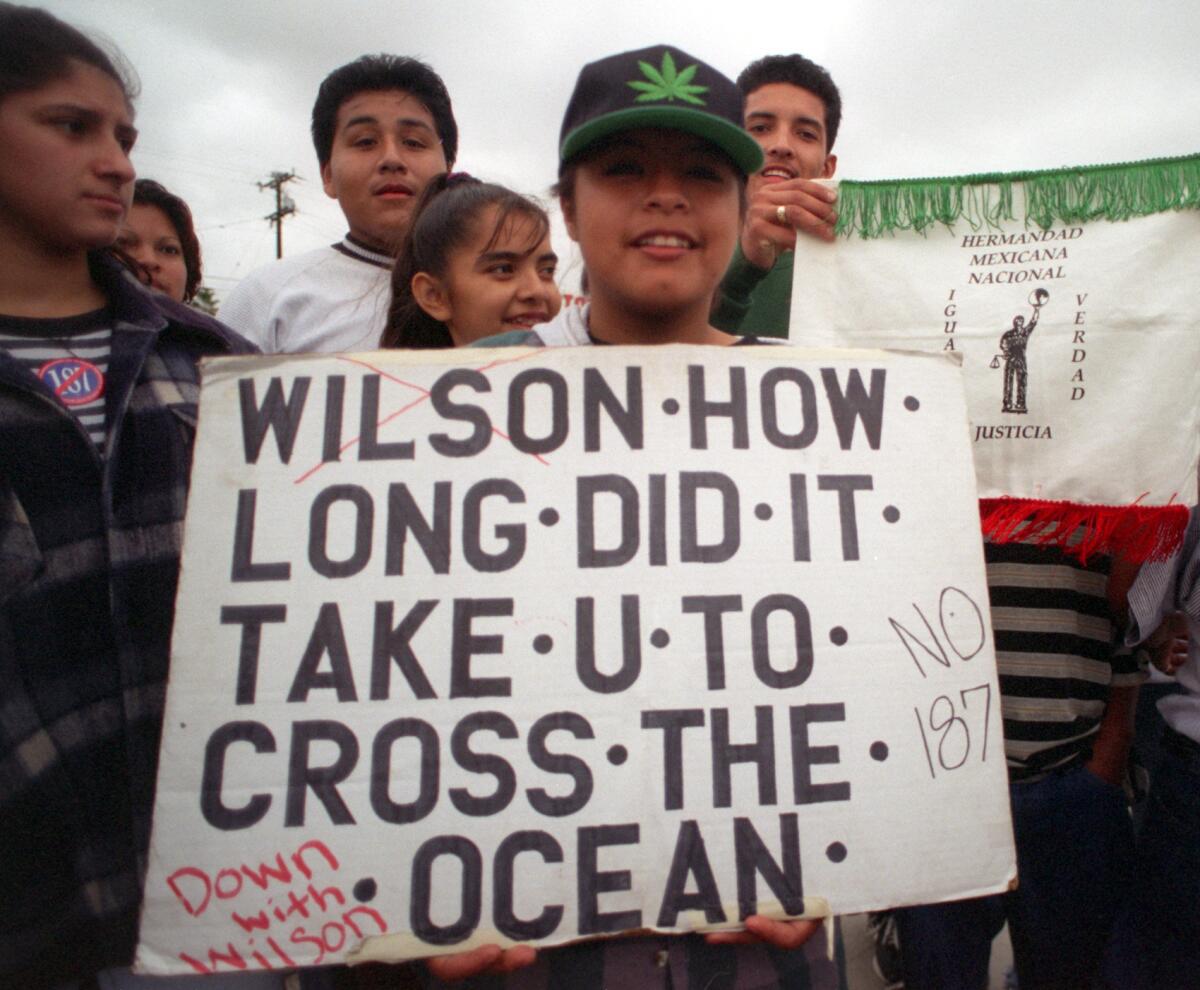

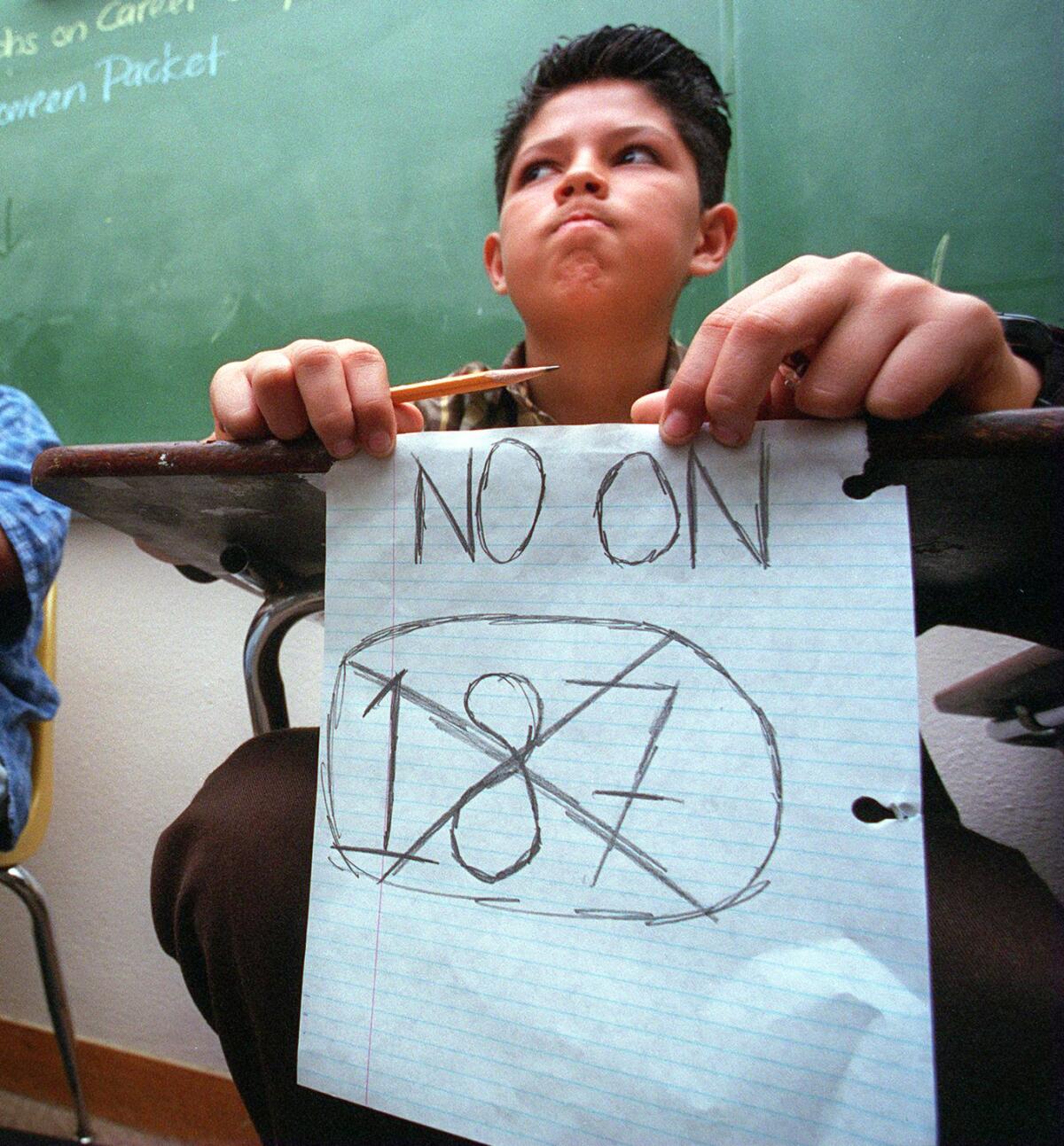

The student marches were the culmination of a month of anti-Proposition 187 teach-ins, debates, letter-writing campaigns and some of the largest protests California had seen since the Vietnam War.

And so it went.

After our initial exchange, Wilson walked the same well-worn road he’s carved out over the last quarter-century when reporters have asked him about Proposition 187. His campaign against illegal immigration wasn’t racist. Allegations that he was a bigot were “evil” and a “lie.” Legal immigration is wonderful, and even workers without legal status had “moxie” even as Wilson felt they weighed down California.

He trotted out stats, some of which I found questionable. For example, he alleged that 25% of felons in California state prisons do not have legal status. But California Department of Corrections records show that the estimated foreign-born population in its facilities for 2018 was about 13.5%.

Wilson asserted that two-thirds of all babies born in California by the time he became governor were to mothers without legal status. Wilson’s estimate was off: the Pew Hispanic Center estimates births to mothers in the U.S. illegally in 1990 would’ve made up just 15% of California’s 612,000 births that year.

Wilson also cited a conservative urban legend: that Ronald Reagan felt the 1986 amnesty was “one of the well-meaning but serious mistakes that he had made.” Both the president’s son and former attorney general, Edwin Meese, have denied Reagan ever said that publicly or privately.

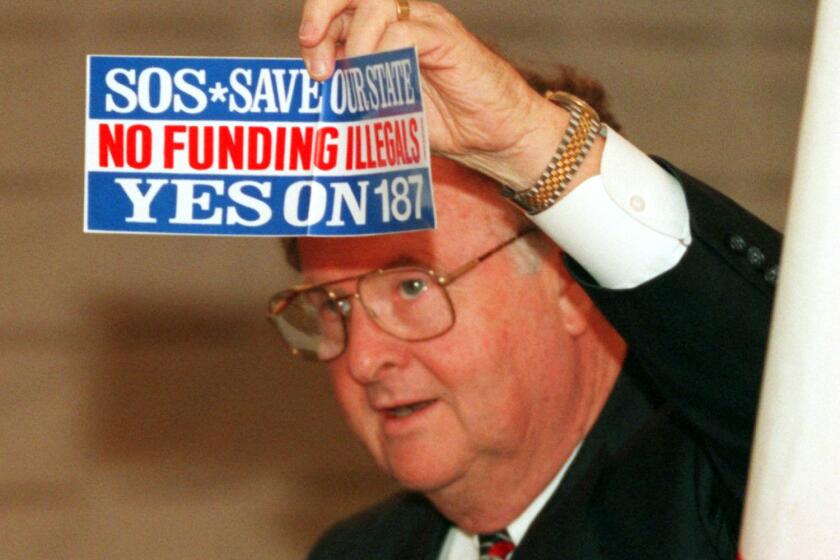

On Proposition 187, he recounted how staff members had urged him not to publicly support the ballot measure because they were afraid he was going to be “introducing a new issue” in the ’94 race. When I reminded him the “They Keep Coming” commercial was released months before he endorsed the proposition, Wilson responded by saying I “disappointed” him by depicting the ad as racist, stating it was “simply a statement of fact” and “not pejorative.”

I pointed out it wasn’t just liberals who thought the ad was racist. Even the political consultants behind Proposition 187, Barbara and Bob Kiley, told me they thought it was.

“If they were consultants,” Wilson chortled, “they were not earning their fees.”

“Can you see why people think that ad’s racist, though?” I responded, pointing out that many Latinos took the “they” as “them.”

We went back and forth until he finally said, “You know, if people were offended, that wasn’t the purpose.”

As the conversation neared 40 minutes, I felt what I was getting out of him was as anticlimactic as the finale of “Game of Thrones.”

I decided to get personal.

“How do you feel,” I began, “that so many Latinos directly credit 187 and your campaign ... against illegal immigration as inspiration for them to enter political life. To, frankly, become radicalized?”

He went on a long aside about public employee unions and the Democrats. So I brought up my cousins: blue-collar guys who grew up the children of immigrants without legal status and had spent their whole lives working with, befriending, or marrying them.

A look back at the events surrounding the 1994 proposition.

Nearly all of my primos own their own homes, run their own businesses; some would like to vote GOP because they can’t stand the hard-left turn Democrats seem to be taking, I told Wilson.

But they’ll never go Republican, because they remember how people like him cast our family as villains.

Wilson’s response: we had been “misinformed” and “misled” about what he actually stood for.

“I find [it] beneath contempt to deliberately mislead people like your cousins, who are good people but who have been taught something that is untrue,” he said. “They’ve been taught that they are surrounded by racists.”

But he had supported denying people like me and my cousins something as basic as birthright citizenship.

“At what point are we supposed to believe you?” I asked him.

Wilson again blamed Democrats and public employee unions for making us believe “something that wasn’t true.” And he also stated that “no one was more vociferous” in supporting him and Proposition 187 “than Latinos who had become naturalized citizens. They resented others being able to cut to the head of the line.”

Wilson’s tone softened when he mentioned how three of his four grandparents were immigrants, including a maternal grandmother who came to the U.S. on a boat as a 16-year-old in steerage class. He took the mildest issue with Trump’s scorched-earth rhetoric on illegal immigration, even if he agreed with the president’s critiques. I pointed out that Trump also wants to reduce legal immigration, but Wilson didn’t respond.

Wilson even expressed some sympathy for recipients in the program known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, immigrants who came to this country illegally as children. (And whose future is now before the U.S. Supreme Court). But while he would “recognize” DACA recipients with legal status, he was afraid that would “encourage future amnesty.”

Eventually, Wilson tried to turn the tables on me.

He had read my essay for the Los Angeles Times, about how I was one of the few students at Anaheim High who did not participate in student walkouts against Proposition 187. “It took some guts on your part to do that,” he said, a smile on his face. “Not to be like all the others. Congratulations.”

I stumbled at first, surprised. I sputtered out that I was also the only one among my classmates to create a career out of bashing Proposition 187.

“But it’s high time,” Wilson said, “that you got over it.”

Out of my mouth, a droll “Really?” hung in the air.

He was speaking to me, but Wilson was really addressing my generation of Latinos. So I’d answer for us.

Proposition 187 was overturned, but the battle over the initiative taught anti-immigration groups how to better fight for their restrictionist cause.

“When I hear about illegal immigration,” I started, “I have to reduce it down to my dad, who came to this country in the trunk of a Chevy, and all the other people who I know were undocumented. So when I hear that people say illegal immigration ruined California, I look around and I say, ‘We have pretty good lives and we’ve created, we’ve done everything that the United States asked us to do.’

“So how are we supposed to feel?” I concluded.

We looked directly at each other. He got quiet for seconds that felt like eons.

“Well, I would have to say this,” he finally said. “There are a lot of people who are in that situation and I’m not happy about it.”

It wasn’t really an answer, and he had little else, so we moved on.

Twenty minutes later, we shook hands. Our talk was over.

But as I left his Century City offices, Wilson gave me a gift: an article by my colleague, Sarah Parvini. She had written about how conservatives were leaving California for “redder pastures.”

He mentioned it when I had asked whether Prop. 187 created the California we live in today.

“It’s certainly helped,” he had responded. “And frankly, [the] California we have today needs fixing. Desperately needs fixing.”

But here’s the thing: That article Wilson admired was penned by someone who, like me, was also a child of immigrants.

And I guess you can say Wilson, in his own strange way, became a political father of a California he never intended to sire.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.