Prop. 187 flopped, but it taught the nation’s top immigration-control group how to win

- Share via

On Oct. 1, 1981, just a week after becoming deputy commissioner for the Immigration and Naturalization Service, Alan C. Nelson had lunch with the intellectual godfather and fundraiser for America’s modern-day anti-immigration movement.

John Tanton was a Michigan ophthalmologist who, two years earlier, had created the Federation for Immigration Reform (FAIR), a nonprofit organization with the singular mission of reducing immigration, legal and not, to the United States.

He and FAIR President Roger Conner wanted to size up Nelson to see how “we can solve the immigration problems facing the United States,” according to an Oct. 20, 1981, letter Tanton wrote to Nelson that’s part of Tanton’s archives at the University of Michigan.

Nelson and his INS Western regional commissioner, Harold Ezell, were no ideologues when they joined the federal agency. But by the time they left in 1989, both were committed warriors against illegal immigration, thanks in big part to FAIR.

The tall, gravelly voiced Nelson and squat, bombastic Ezell — former members of Ronald Reagan’s California gubernatorial Cabinet — worked closely with FAIR during their time in Washington. The two turned illegal immigration from an issue important only in border states into a national bogeyman by taking their bailiwick to D.C., Sacramento, and beyond.

Nelson and Ezell’s relentless advocacy helped dress the stage for the bitterly partisan immigration debates of the past generation.

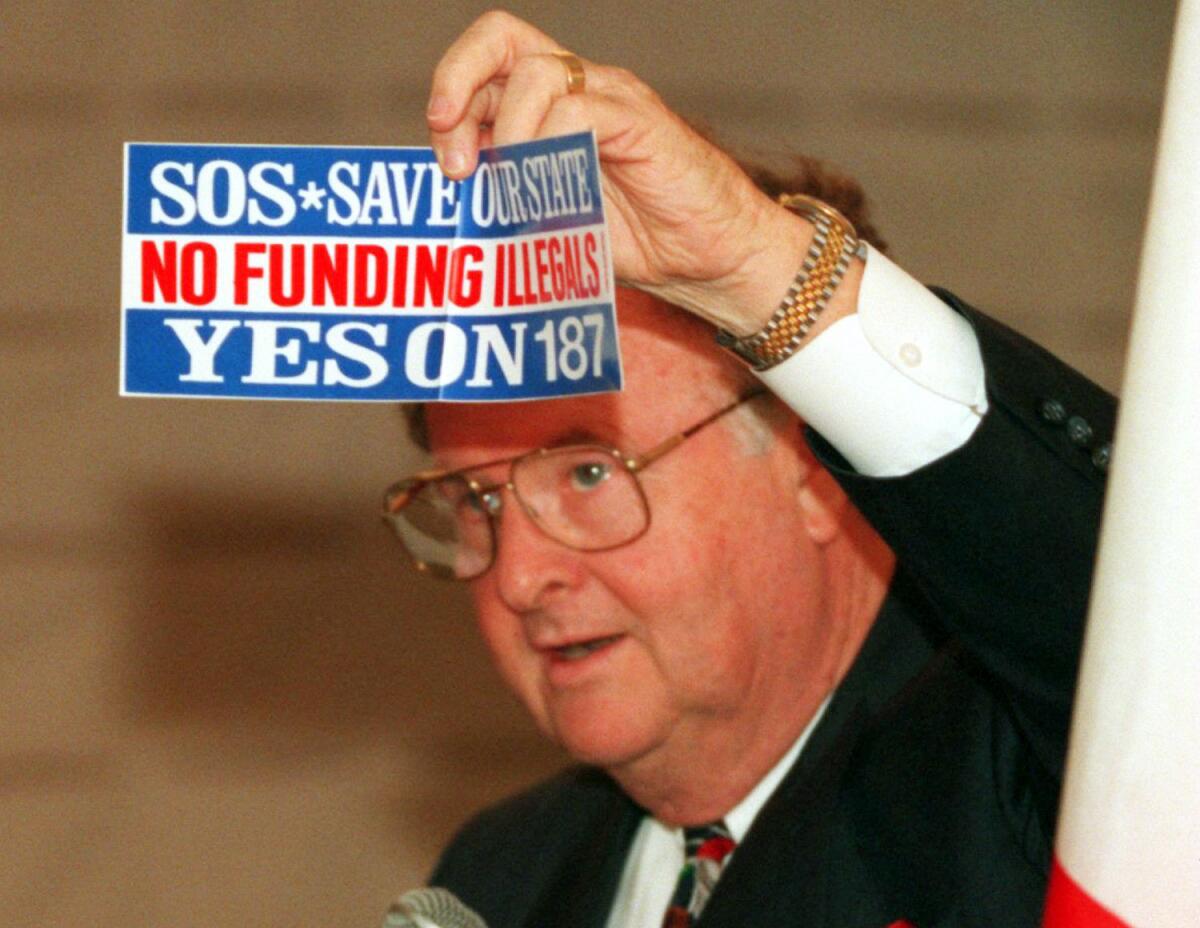

Their efforts culminated with Proposition 187, the landmark 1994 California ballot measure Nelson and Ezell wrote that sought to deny social services and public education to the state’s undocumented immigrants and that voters approved by a 59%-41% margin.

Proposition 187 backfired in California — over the 25 years that followed, it influenced a generation of Latino voters to side with Democrats and transformed state politics to the point where California is now a sanctuary state. Nowadays, it’s a parable that Latino activists tell to warn politicians about running on a nativist platform lest they invite a backlash.

Host Gustavo Arellano looks at how Prop. 187 helped turn California into the progressive beacon it is today.

But far less told is how the battle over 187, which a federal judge ultimately ruled unconstitutional in 1997, also taught anti-immigration groups how to better fight for their restrictionist cause.

And no group learned that lesson better than FAIR.

By studying 187’s initial win and eventual loss in California, it constructed a blueprint that the organization replicated nationwide: Fund citizens groups to drum up populist anger against illegal immigration, help craft legislation and laws for state and local government, and inspire a pipeline of true believers to enter politics.

In the process, FAIR transformed from an inside-the-Beltway group into a powerful lobbying force whose influence reaches all the way to the White House. There, alumni like acting U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Director Ken Cuccinelli, agency ombudsman Julie Kirchner, longtime pollster Kellyanne Conway, and longtime ally Stephen Miller hold Donald Trump’s ear on immigration matters.

None of this seemed possible when Nelson and Tanton first met. (The two men would not live to see any of this unfold; Nelson died of a heart attack in 1997 at 63 and Ezell of liver cancer a year later at 61).

Nelson, who had spent the previous six years as a corporate lawyer for Pacific Bell, admitted he knew “nothing of immigration,” according to notes Tanton took of their initial encounter.

But Tanton replied that the new deputy commissioner’s ignorance was “a strength rather than a liability.”

“You are presiding,” Tanton wrote to him afterward, “over one of the most significant determinants of our country’s future!”

Tanton, an ardent environmentalist who initially believed that reducing immigration would save the nation’s natural resources but later saw it as a way to protect the country from a “Latin onslaught,” was just starting to plot out how to turn FAIR into a powerhouse.

Four months after meeting Tanton, Nelson was promoted to INS commissioner. He invited the FAIR founder to his swearing-in ceremony.

FAIR couldn’t have discovered a better blank slate upon which to sketch out the potential of the group’s message than Proposition 187 and its authors.

Nelson was “a real trouper,” said Dan Stein, FAIR’s president since 1988. And Proposition 187 has “a direct lineage to Trump,” Stein added, “an escalating curve, from 1994 all the way to 2016.”

The student marches were the culmination of a month of anti-Proposition 187 teach-ins, debates, letter-writing campaigns and some of the largest protests California had seen since the Vietnam War.

Letters from Tanton’s archives show that Tanton and Conner regularly talked with Nelson and shaped not only his worldview, but also the policies of the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

Nelson addressed FAIR luncheons and met periodically with Conner, who sent him “suggested themes for immigration hearings.” He also directed the group’s spokesperson to work with Nelson’s staff on “ways to improve” the language of a proposed immigration bill that turned into an amnesty for over 3 million immigrants living in the U.S. illegally.

As Nelson and FAIR quietly worked Congress, Ezell railed about an “invasion” in California.

Appointed in 1983, Ezell was a former executive of the Wienerschnitzel hot dog chain whose bluster made him a media favorite. He took politicians on nighttime visits to the U.S.-Mexico border, asked INS agents to check the residency status of Salvadorans who spoke at Los Angeles City Council meetings and advocated deporting immigrants who won the California lottery.

Of detained immigrants, Ezell told Time magazine, “If you catch ‘em, you ought to clean ‘em and fry ‘em yourself.”

Eventually, Ezell — who described himself in the media as a FAIR “contributing member” — asked Conner for help in creating Americans for Border Control, the country’s first citizen’s group dedicated to combating illegal immigration.

Composed almost exclusively of Ezell’s friends, ABC’s actions were mostly limited to cheering on immigration agents during raids in Orange County. But the group pleased Tanton, who funded them through another nonprofit he controlled called U.S. Inc.

In 1989, Nelson and Ezell left the INS but continued their crusade in California. The state was about to go through its worst economic crisis since the Great Depression at a time when changing demographics angered many longtimers.

It was ripe turf to preach FAIR’s gospel.

Ezell joined anti-immigration groups in Orange County even while helping wealthy foreigners apply for so-called investor visas. This loophole in immigration law allowed non-Americans to qualify for residency if they invested $1 million in a business that created at least 10 American jobs.

Nelson, who became a lobbyist for FAIR, frequently held news conferences at the Capitol in Sacramento, claiming that the state had an illegal immigration problem, and urged lawmakers to act. “We’ve declared war on drugs. We’ve declared war on drunken driving,” Nelson once intoned. “How about on illegal immigration?”

By 1993, Nelson and Ezell’s efforts had paid off.

During the 1993-94 legislative session, Assembly members and state senators introduced 83 bills against illegal immigration. Four FAIR-backed bills — to deny government jobs and driver’s licenses to immigrants in the U.S. illegally, ban cities from declaring themselves sanctuaries, and expedite deportation of prisoners — passed.

“Our message is finally getting through,” Nelson told the Los Angeles Times in November 1993. “It’s our turn at bat.”

By then, he had a new project to work on: Proposition 187, which Stein described as the “first major citizen-based initiative” against illegal immigration — but said that FAIR had no role in creating.

A look back at the events surrounding the 1994 proposition.

Ezell and Nelson publicly distanced themselves from FAIR once news emerged of their planned initiative. Nelson left his lobbyist gig; Ezell created yet another grassroots group, Americans Against Illegal Immigration, which helped to mobilize on-the-ground volunteers for 187.

The proposition’s opponents, late in the campaign, tried to paint the proposition as hate legislation bankrolled by FAIR. But all they could find was a $100 donation by Tanton and radio ads that attacked proposition opponents as “special interests” who wanted “an open-ended commitment to pay for services that, like a magnet, attract a never-ending flow of illegal immigrants to our state”

Stein, FAIR’s president then and now, acknowledged that his group helped with “a few logistical things along the way” in the Proposition 187 campaign, including $300,000 spent on ads, and media appearances to spread the message.

Proposition 187 was a “watershed moment in terms of transforming America’s immigration moment into a national grassroots effort,” Stein said. To credit FAIR for it and not the “folks on the ground ... wouldn’t be fair, or accurate.”

But Tanton watched 187 with interest.

In a fall 1994 editorial for his journal, “The Social Contract Press,” he predicted that if the proposition failed at he ballot box, any joy felt by opponents would “shortly fade when they learn that the defeat has only hardened [187 supporters], stiffened its resolve, and broadened its objectives to include legal immigration.”

He visited pro-187 volunteers in Sherman Oaks in early 1995 to offer his congratulations, tried to arrange meetings between 187’s creators and other anti-immigrant activists across the U.S., and asked a trust tied to Cordelia Scaife May, a reclusive Pittsburgh philanthropist and major FAIR funder, for $25,000 so he could pay some of the expenses of two 187 volunteers, to “keep them encouraged and working for our cause,” according to letters at his University of Michigan archives.

Through U.S. Inc., Tanton supported American Patrol and the California Coalition for Immigration Reform, two influential Southern California groups whose apocalyptic theories that illegal immigration was an effort by Mexico to retake the American Southwest now passes as truth for much of the nation’s anti-immigrant movement.

Tanton also used 187 to ask donors for more money to fund similar measures across the country. In a letter to Lawrence Kates, a major Los Angeles landlord who had donated a significant amount of money to FAIR in its early days, Tanton proposed the two “keep the heat on the issue” and work together against “the decline of European-American majority and the resultant cultural consequences.”

“You and I owe it to our kids, to our culture, and to ourselves to team up on this,” Tanton wrote.

His pleas worked: Groups tied to Scaife May would go on to donate $103.9 million to Tanton’s organizations from 2003 to 2017 alone.

With that windfall, FAIR and its legal arm, the Immigration Reform Law Institute, pushed for anti-immigrant measures from Hazleton, Pa., to Farmer’s Branch, Texas, to Arizona and beyond. Keeping 187’s ultimate defeat in mind, Stein said the group made sure such ordinances “were drafted with experienced counsel.”

Many of them have since been declared unconstitutional. But that hasn’t deterred FAIR, which filed an amicus curiae brief last year in a federal lawsuit by the Trump administration targeting California’s sanctuary state policies.

“What we learned from 187 is that we need to be there at the beginning” on the legal and grassroots end, Stein said. He remembered how when FAIR first learned about the proposition, the board debated whether they should “stay out of it, or get involved.”

“But I said that when your troops are out there in the field of battle, you can’t just stay there and watch,” Stein said. “You’ve got to get involved.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.